A new investigation by the Ukrainian media outlet TEXTY reveals that two of Russia’s biggest museums – the State Hermitage Museum and the State Historical Museum – hold over 110,000 artifacts that were taken from modern-day Ukraine.

The study excluded icons, artwork, and weapons, as their origins are harder to trace. It also did not look at objects looted during the current war in Ukraine.

“It was from Muscovy and later the Russian Empire that Ukraine suffered the biggest losses of cultural artifacts,” says Serhii Kot, a Ukrainian scientist who researched the fate of Ukrainian artifacts.

According to Kot, artifacts were forcibly removed from Ukraine to Russia through looting by troops, organized extraction by authorities, archaeological expeditions, sales, and relocations. This occurred over centuries, starting from imperial Russia through the Soviet era.

“During all the years of rule over Ukraine, the Russian government did not set up a single state museum on its territory,” Kot states.

The Hermitage Museum, founded in 1764, received many artifacts from Ukraine.

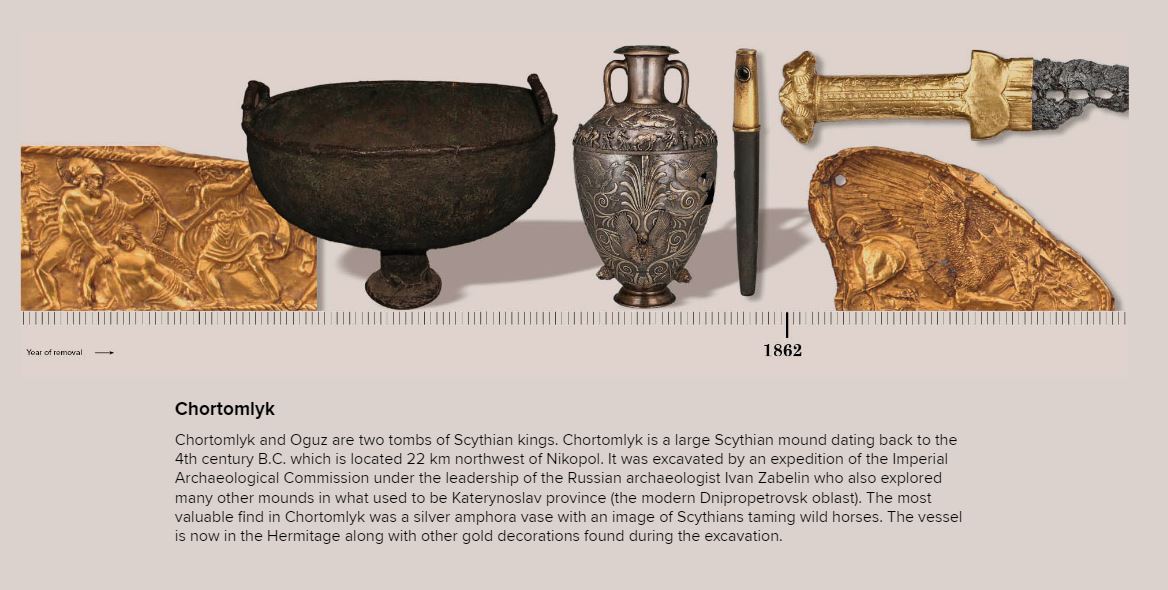

“The [Hermitage] collection of Scythian-Sarmatian antiquities is one of its kind in terms of completeness and artistic value. First-class gold items from the burial mounds of the Scythian and Sarmatian nobility such as Kelermes and Ulsky, Solokha, Chortomlyk and Alexandropol, Khokhlach (Novocherkask treasure) barrows and many others are the stars of the collection,” according to the book “The History of the Hermitage.”

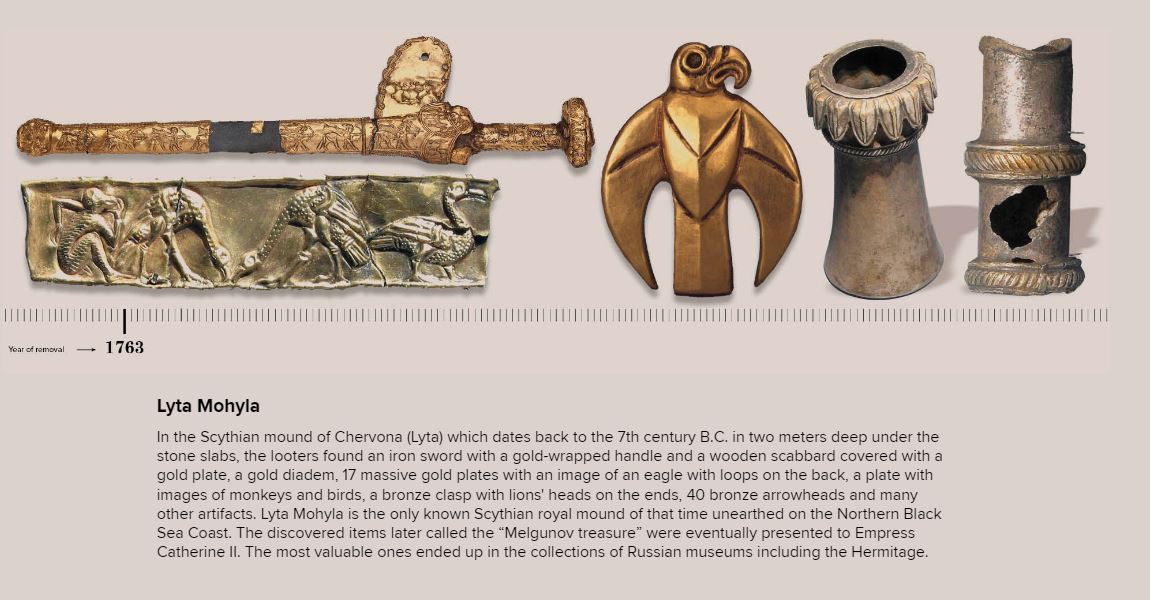

The study found over 33,000 artifacts in the Hermitage and over 77,000 in Russia’s State Historical Museum originating from locations now in Ukraine. Most are everyday items like pottery fragments, tools, etc. But there are also gold, silver, and gemstones. Some of them are from an ancient Scythian burial site, Lyta Mohyla [Cast Grave].

“Although the ‘Melhuniv Treasure’ from Lyta Mohyla mound included dozens of valuable items and hundreds of gold accessories found in Luhova Mohyla, the online catalogs contain only a few items from those sites. There are only three silver objects from the royal Scythian mound Ohuz near the village of Nizhny Sirohozy in Kherson Oblast in the online catalog of the Hermitage. However, the description of the treasure mentions dozens of gold plaques unearthed by the archaeologists. It would be naive to expect the Russians to disclose information about their possessions on the Internet — especially considering their cover-up culture and the constant ranting about the decolonization in Ukraine,” the study states.

Ukraine has tried to get the artifacts back, but Russia refuses. “From the legal standpoint, it is impossible,” says Denys Yashny, a researcher at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra national reserve.

The study located artifacts by searching online museum catalogs and tracing inventory numbers, names of archaeological sites, collections, and other clues.

However, Texty found that many artifacts in the Russian museum catalogs lacked photos. Without photos, it is harder to conclusively identify the origin of an artifact if the catalog description lacks details like the archaeological site where it was found.

The authors imply that the lack of photos for so many artifacts is not just a coincidence, but rather a deliberate attempt by Russia to obscure the provenance of looted Ukrainian items in their museum collections when other attributes are inconclusive.

For instance, the museum only stated the place where a XII-century fresco had been created (ancient Kyiv) “without providing information about the place of discovery and the archaeological site or uploading a photo. The exhibit is part of the “Ancient Russian Archeology” collection, which includes objects found both in the territory of present-day Ukraine and in the principalities of the ancient Kyivan Rus that are today part of Russia.

Texty did not include the fresco in their collection of items because, although it is likely that the fresco indeed originates from modern-day Ukraine, definite verification is impossible. Thus, the actual number of Ukrainian treasures held hostage by Russian museums is in reality higher than 110,000.

Related:

- Russians stole treasures from 40 Ukrainian museums, including golden diadem of the Huns

- Russian plans to “evacuate” treasures from occupied Crimea

- Army of marauders: the long history of Russian military looting, pillaging, and stealing

- Tribunal or restitution? Ukraine eyes ways to return one of its richest art collections looted by Russia