A joint report by the KSE (Kyiv School of Economics) Institute and Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions has revealed how despite Western sanctions, Russia is continuing to circumvent restrictions to gain access to crucial components for replenishing its missile stockpile and sustaining strikes in Ukraine.

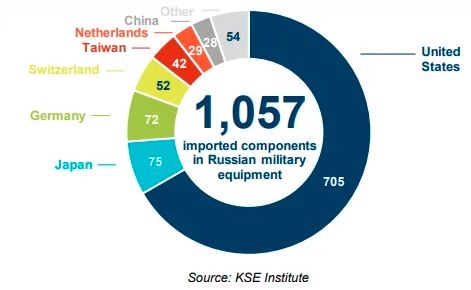

The report finds that Russia continues to source Western-made components for its military hardware despite existing sanctions. A large portion of Russia’s modern weaponry relies on sophisticated electronics imported from countries such as the US, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, Israel, and China.

These components, in some cases, are dual-use goods that are commercially available and challenging to control via export restrictions.

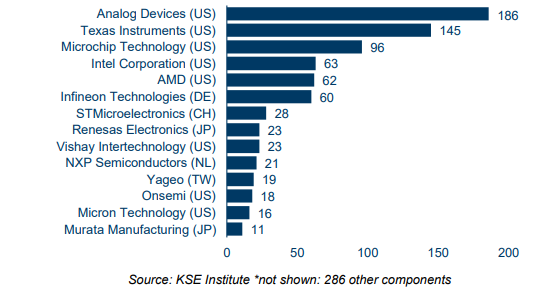

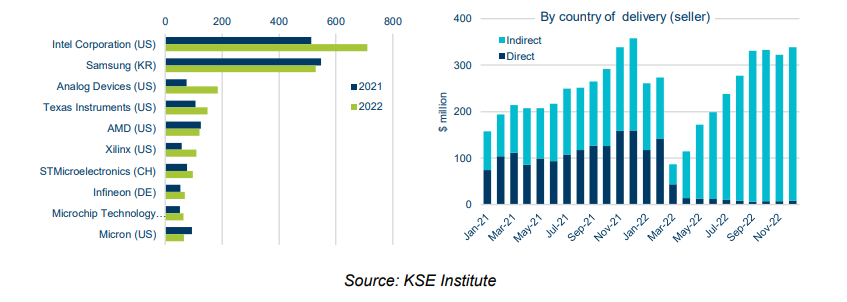

The London-based Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) estimates that over 450 foreign-made components are used in 27 different Russian equipment systems. Remarkably, about ten companies supply over 200 components, nearly half of the total. Many of these components are subject to US export controls, yet Russia manages to obtain them, possibly through third-party intermediaries.

Russia has developed a system for concealing the original source of these items, often using third countries as intermediaries. A significant portion of the computer components used in Russian ballistic and cruise missiles are allegedly procured for non-military use in Russia’s space program, ROSCOSMOS, which has been utilized to acquire technology with both civilian and military applications.

Companies worldwide, including those in the Czech Republic, Serbia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Türkiye, India, and China, appear willing to take risks to meet Russian procurement demands. An investigation found that since the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, 75% of US microchips were supplied to Russia through Hong Kong or China, despite manufacturers claiming to have suspended all operations with Russia. This is primarily possible due to lesser-known chip traders and shell companies which can evade US sanctions more easily than established distributors.

The debate around whether sanctions have been effective so far is mixed. The Center for Strategic and International Studies reports that shortages of certain high-end components are causing the Russian Ministry of Defense to substitute them with lower-quality alternatives. Yet, the Free Russia Foundation suggests that the sanctions regime was only able to disrupt the access to Western technology in the short term, with Russia quickly establishing alternative routes. Consequently, Russia’s imports of dual-use goods now exceed pre-war levels.

Overall assessment of Russia’s military capabilities

The KSE Institute and Yermak-McFaul Foundation note that although Russia has systematically implemented import substitution programs since 2014 to reduce its reliance on foreign components, particularly in defense, its continued use of foreign-sourced high-tech components reveals a substantial ongoing dependence.

Despite this, the impact of export controls is limited by three factors:

- Long-term stocks: Research has revealed that Russia maintains stocks to fulfill long-term contracts, equivalent to roughly three years of production. Hence, any restrictions aiming at production will experience a lag in impact. However, during times of war, when production needs increase significantly, Russia is likely to utilize these stocks.

- Illicit channels and grey areas: Evasion of sanctions has been noticed in several instances. Tactics involve:

•using intermediaries in countries not under sanctions,

•restructuring companies to hide sanctioned entities or individuals,

•and shifting final assembly to Russia after purchasing components instead of buying finished sanctioned products.

•Additionally, sanctioned Western components have been identified in drones that Iran supplied to Russia.

- Inconsistent export controls and weak enforcement:

•The success of the above evasion schemes is mainly due to loopholes in the sanctions and export controls regime. Enforcement issues, particularly concerning identifying end users of products, are partly responsible.

•The issue is further exacerbated by inconsistencies in the list of dual-use goods across sanctioning nations, which doesn’t align with the customs codes of the Harmonized System (HS). Consequently, it becomes challenging to identify if a particular shipment falls under sanctions. The US has recently issued a list of HS codes that need special attention, and the EU is expected to follow suit.

Although Russia’s significant stockpiles have made military production somewhat resilient to sanctions and export controls, the absence of high-tech components has emerged as a major constraint.

The report discusses various types of military equipment and how they’ve been impacted by sanctions and export controls:

1. Tanks and other armored vehicles

Uralvagonzavod, Russia’s sole tank manufacturer, was forced to cease operations in March 2022 due to a shortage of components (mainly bearings) following the implementation of export controls. However, production has resumed and increased through procuring inputs from alternative sources (Türkiye being the largest supplier of bearings in 2022) and the implementation of 24-hour shifts.

The focus has been on modernizing existing tanks and repairing damaged equipment rather than producing new units, as they face a shortage of specific equipment like the Sosna-U multichannel thermal imaging gunner’s sights.

- Russian army gets new T-80BVM tanks despite western sanctions

- Russia “buying back” its tank and missile parts from Myanmar and India – Nikkei

- Russian defence manufacturing sector resorts to using convict labour – British intel

- How to finally stop “Putin’s favorite factory” from producing cheap tanks

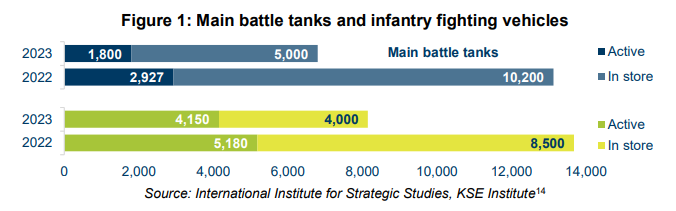

Kurganmashzavod, the primary manufacturer of Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFV), is in a similar situation, also operating round-the-clock and focusing on modernizing existing IFVs. Despite these efforts, the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) reports a considerable decrease in active tanks and IFVs since the full-scale invasion began, with a 39% reduction in active tanks and a 20% drop in active IFVs. Numbers for such vehicles in storage have also fallen by 51% and 53%, respectively (Figure 1).

2. Artillery

Russia is facing difficulties supplying artillery shells. The number of artillery rounds has contracted significantly – approximately 75% – since last summer when Russia launched 40,000-50,000 rounds daily in the Donbas. Nonetheless, stockpiles remain numerous, even if some are old and less reliable.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) assesses that munitions constraints will likely prevent Russian forces from maintaining high pace operations in the Bakhmut area and elsewhere in the near term, adding that the fact Russia has depleted large stockpiles in Belarus is further evidence that a renewed offensive from Belarusian territory is unlikely.

3. Missiles

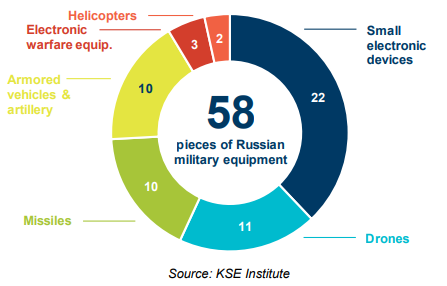

While the frequency of missile attacks on Ukrainian territory, including critical infrastructure and civilian buildings, has declined, Russia continues to consistently strike civilian infrastructure using missiles and drones. To augment its supply, Russia is not only attempting to increase production (Figure 2) but is also reportedly exploring buying missiles from North Korea and additional drones from Iran, which come at a significantly lower cost.

Evidence of equipment constraints is reflected in the unconventional use of some missiles (Figure 3). For instance, attacks on Ukraine have been executed using S-400 (and S-300) missiles, originally designed for air defense and thus lacking precision when used against ground targets. The immediate deployment of newly produced cruise missiles, as indicated by debris analysis showing the use of missiles manufactured in Q1 2023, signifies alarmingly low stocks.

Ultimately, the most substantial impact on Russia’s military capacity appears to stem from extraordinary battlefield losses. Given its limited ability to ramp up production swiftly and its restricted access to some critical components, Russia currently struggles to rebuild its stocks at a sufficient pace. However, considering the extensive scope of military and dual-use goods export controls, the effects should have been more profound. This suggests potential violations and circumventions of restrictions.

The KSI Institute and Yermark-McFaul Foundation undertook a detailed analysis of trade with critical goods to identify specific issues associated with existing export control regimes.

Analysis of Russian imports of critical components

The analysis begins by using information on Russian military equipment recovered on Ukrainian territory since the start of the full-scale invasion. The report found that of 58 pieces of Russian military equipment recovered, 1,057 individual foreign components were discovered. Microchips and (micro-)processors account for over half of all components (Figure 4).

In addition, 155 companies were identified as producers of these components, with headquarters in 19 countries.

The report uses a comprehensive, micro-level dataset on Russian trade. All 1,185 HS codes found in these transactions are analyzed on a case-by-case basis to determine which goods should be considered potential inputs for Russian military production and which are purely civil.

385 HS codes were identified and defined as “critical components” for the analysis. Of the codes, less than half (170) are included in the European Union’s dual-use goods list.

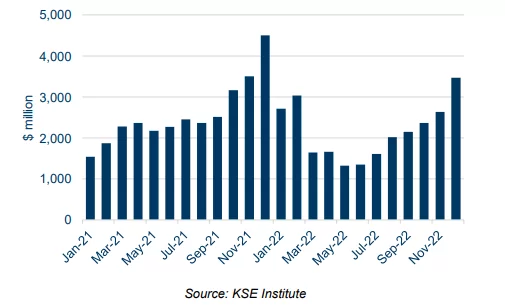

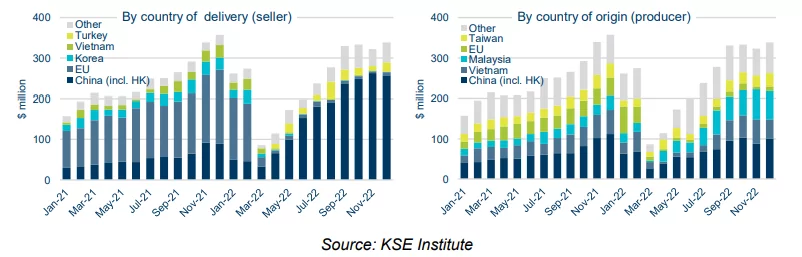

The report then discusses four overall dynamics of these “critical components” imports. It reveals several key developments driven by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the introduction of export controls by the sanctions coalition (Figure 7). These dynamics include:

- Building up stocks: In Q4 2021, Russia significantly increased its imports of critical components, likely as a precautionary measure for future acquisition challenges in its military production.

- Post-sanctions drop: Following the introduction of export controls by Ukraine’s allies, there was a sharp drop in imports by nearly 50% during March-June.

- Recovery in H2 2022: Russia adapted by Q4 2022, with imports of essential components rising by 9.3% compared to 2021, implying a possible workaround for obtaining Western components.

- Overall decline in full-2022: Despite a 16% overall decrease in imports in 2022 due to temporary disruptions, if Q4 2022 import levels persist, 2023 may witness a 30% increase over 2022 and a 9% increase over 2021.

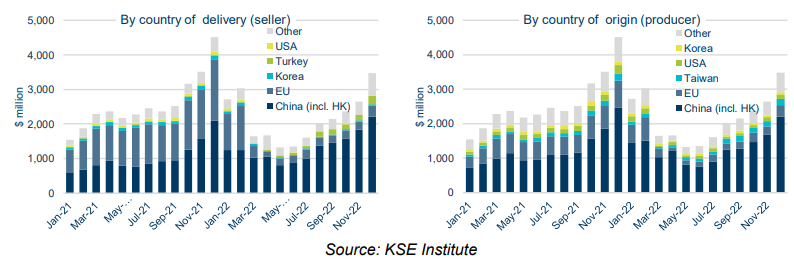

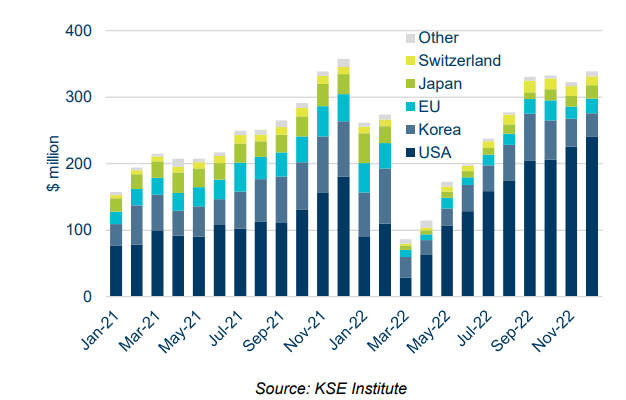

Next, the analysis examined where critical components were acquired from (Figure 8). The report found that although China did not impose any export controls, Russian imports noticeably fell in the immediate aftermath of the invasion. This could have been due to the fact that critical components either manufactured in China or sold via China are, ultimately, products of Western entities. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that China’s share in Russian imports of critical components has risen markedly since the imposition of export controls. By Q4 2022, China’s share as a country of delivery reached 53% (39% in 2021) and as country of origin 63% (48% in 2021). The difference between the two illustrates that a substantial share of Russian imports, around 10%, is now acquired from third-country manufacturers via Chinese and Hong Kong-based intermediaries

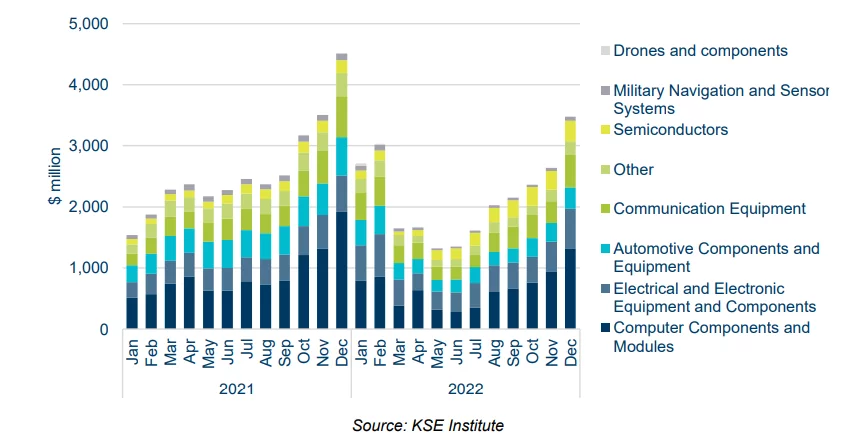

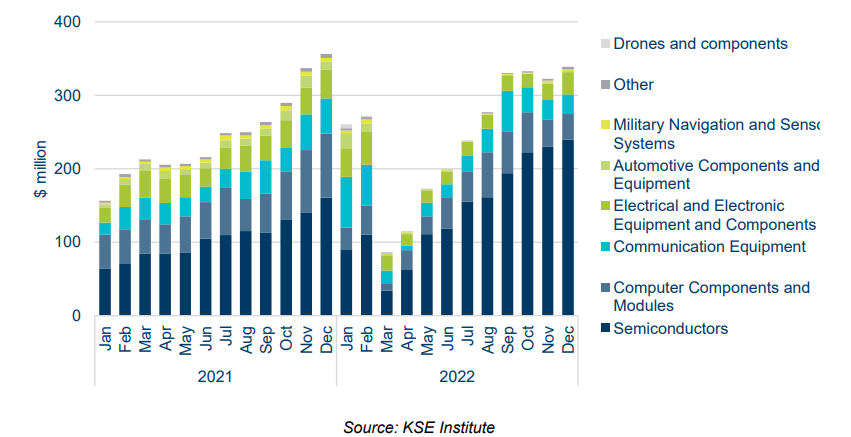

The analysis then investigated what types of critical components Russia has been importing. It examined the dynamics regarding semiconductors and integrated circuits, which are key targets of export controls. The analysis had three key findings in this area:

1. Broad-based pickup in H2 2022.

The rebound in Russian imports of critical components towards the end of last year was relatively homogeneous across categories. However, some are particularly important, e.g., computer components and electric and electronic equipment.

2. Semiconductors, especially western-made, play a key role.

Semiconductors were the most commonly found critical component in Russian military equipment, and specifically, Western-made microchips were identified in every type of equipment investigated by Ukrainian authorities. Chinese substitutes for Western-made semiconductors continue to lag behind Western products’ technological advancement and quality.

3. Imports of semiconductors pick up speed

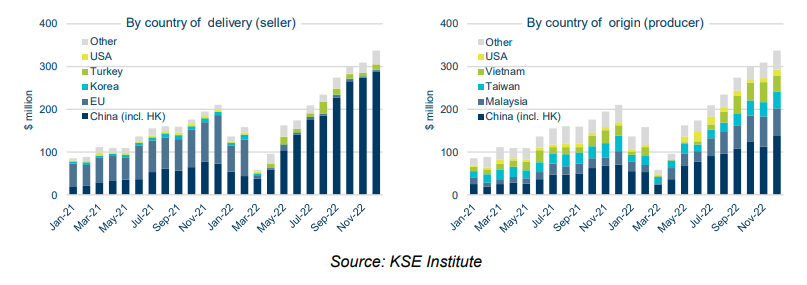

Semiconductors show similar developments as overall critical components, including a late-2021 pickup (+56% in Q4 vs. Q1-Q3 average), a sharp drop in March through to April (-48% vs. January and February period), and a subsequent rebound (Figure 10). It was also revealed that 55% of semiconductors that were acquired from China and Hong Kong were, in fact, produced somewhere else (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Semiconductor imports from China, delivery vs originThe analysis focuses on a subset of 155 companies (including subsidiaries) whose products were identified in Russian weapons. These accounted for 11% of critical component sales to Russia in 2022 (equivalent to $2.9 billion).

- Sales to Russia rebound quickly. For these companies, which includes some of the largest Western manufacturers of electronics such as Intel Corporation and AMD, a typical pattern is observed of late-2021 surge, March-April drop, and H2 2022 recovery (Figure 12). Their export of critical components to Russia stood 35% above their 2021 average in Q4 2022. This translates to essentially no change against 2021.

- Business entirely through intermediaries. Shipments are almost entirely routed via third countries now (Figure 12) and the share of indirect sales rose from 54% in 2021 to 98% in Q4 2022. China, again, plays a critical role here (Figure 13) with more than three-fourths of sales to Russia being conducted via an intermediary in China in Q4 2022 (compare dot 22% in 2021). Consistent with previous findings, products are actually manufactured outside of China to a considerable extent.

- US-based companies dominate. Upon closer inspection of the companies involved, US-based entities represent the largest share, with its share having increased since the full-scale invasion (Figure 14). In 2021, US companies accounted for 45% of imports; by Q4 2022, this number surged to 68%.

- Continued sales of semiconductors. In line with earlier findings that high-quality substitutes for Western semiconductors are difficult to acquire, the data shows that these products have grown in importance. Not only have their sales to Russia more than recovered from the post-sanction drop, they make up a large share of the total now at 70% in Q4 2022 compared with 43% in 2021 (Figure 15).

Finally, the analysis examined how goods produced on behalf of major Western companies reached Russia in March-December 2022. Three observations are made:

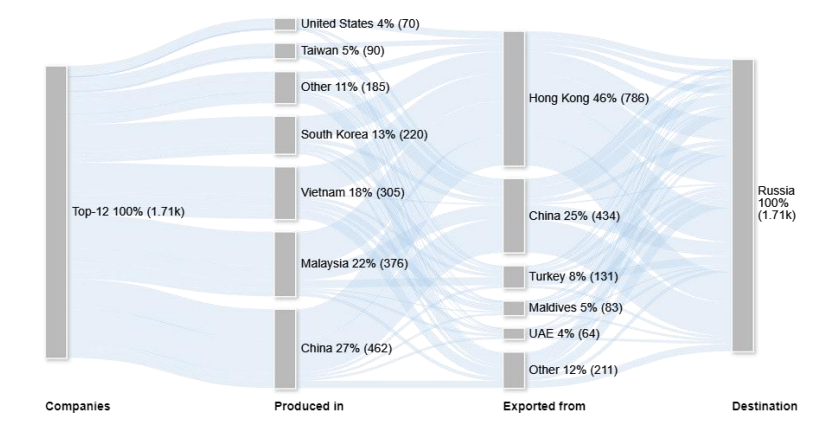

- Production locations. Close to 80% of all critical components were produced in four countries: China (27%), Malaysia (22%), Vietnam (18%), and South Korea (13%).

- Export locations. In terms of the countries from which these goods were ultimately exported to Russia, three are of particular importance and together account for, again, close to 80% of the total: Hong Kong (46%), China (25%), and Türkiye (8%).

- Structures differ across companies. There is no common pattern; goods from different producers are manufactured in different locations and reach Russia through different countries and intermediaries.

Policy Recommendations

The KSE Institute and Yermak-McFaul Foundation identify that the continued import of critical components by Russia are manifestations of several separate issues of the existing export regime:

- Entities under coalition jurisdiction engage in sanctions violations; in other words, they undertake activities that are illegal;

- Entities under coalition jurisdiction engage in sanctions circumvention; in other words, they undertake activities that are legal but opposed to the sanctions regime’s objectives;

- Entities outside of coalition jurisdiction, i.e., third-country actors, contribute to sanctions violations and/or circumvention.

The authors of the report outline policy recommendations:

To improve enforcement

- Boost information sharing: To enhance enforcement of military and dual-use goods export controls, authorities should foster improved data sharing systems concerning sensitive trade activities. This includes customs data from sanction-allied countries and third parties, potentially involving academic and think tank communities.

- Encourage joint investigations: Authorities across coalition nations should collaborate in investigating possible sanction violations or circumventions. Since trading critical components often involves numerous actors across various jurisdictions, joint investigations could prevent “jurisdiction shopping,” particularly relevant for EU member states.

- Leverage anti-money laundering (AML) framework: Since sanction evasion tactics often resemble those used for money laundering, existing regulatory frameworks for monitoring these activities could be effectively applied to export control violations. AML frameworks, in particular, could track structures in third countries involved in the production and exports to Russia.

- Implement financial sector measures: Financial sector sanctions could enhance the enforcement of export controls and other restrictions due to financial institutions’ pivotal role in cross-border transactions. Imposing additional sanctions on Russian banks could limit import payment channels, facilitating more effective monitoring. Moreover, companies should be mandated to inform banks about potential export-control goods when processing payment requests.

To address sanctions violations:

- Engagement with key companies: Encourage dialogue with firms exporting to Russia to ensure compliance with export controls and provide technical assistance for SMEs that lack capacity to conduct necessary due diligence.

- Information sharing: Authorities need to regularly update clear guidance on sanctions and consider the establishment of a database for companies to access information about potential business partners, including sanctions coverage and past violations.

- Demonstrating consequences: Regulatory agencies need to reinforce commitment to preventing and prosecuting violations by investigating high-profile players to ensure adequate due diligence is undertaken for goods under export control.

- Enhanced documentation: To improve accountability and compliance, there should be increased documentary requirements for transactions and a clear assignment of responsibility within companies for approval of such transactions.

To address sanctions circumvention:

- Align dual-use goods lists: To close existing loopholes, all sanction-imposing nations should align their export control regimes. The classification and approval criteria for “dual use” goods should be standardized across all countries. Dual-use goods should be defined based on Harmonized System (HS) codes to facilitate transaction monitoring.

- Implement broader export controls: Currently, the export controls target specific goods, leaving similar products uncontrolled. Therefore, authorities should expand the scope of export controls to include substitutes for controlled goods. This would also prevent misclassification on customs declarations and mitigate the risk of critical components being diverted for military use.

To address third-country actors:

- Threat of secondary sanctions: The US could use secondary sanctions as a deterrent against third-party entities interacting with sanctioned bodies. This controversial measure could effectively close third-country loopholes, leveraging the potential loss of access to the US financial system as a deterrent.

- EU’s new legal instrument: Despite its opposition to extraterritorial sanctions, the EU is considering new legal grounds to impose restrictions on third-country entities that indirectly contribute to sanction violations.

- Enhanced monitoring of schemes: The authorities should consistently monitor new entities, including shell companies, using all available data sources to understand how they adjust to restrictions and alter the sanctions regime accordingly.

- Provision of technical assistance: Considering the capacity constraints of some third-country entities, particularly SMEs, sanctions coalition authorities should offer technical assistance to ensure compliance with the export controls regime and to prevent unintentional violations.

Related:

- How to cut off the oxygen to Russia’s war machine

- How to finally stop “Putin’s favorite factory” from producing cheap tanks

- Russian companies producing drones and missiles still not sanctioned by the West

- Microchip backalley: Armenia, Kazakhstan help Russia evade sanctions, produce weapons

- Western companies supplied components for Russian Orlan drones despite sanctions – media

- Terror from the sky: a guide to Russian missiles used against Ukraine and how to stop them