Throughout centuries, the history of the Ukrainian language was as turbulent as the history of Ukraine itself. Captured in the words of modern-day Ukrainian are not only memories of the country’s interactions with Russians, Turks, Poles, Hungarians, Germans, and other nations, but glimpses of the ancient Romans, Greeks, Celts, Goths, and, going further, Iranian languages. Maybe there’s a connection with your language, as well?

The Ukrainian word maidan ‘square, plaza’ became known internationally during the Euromaidan revolution of 2013-2014. The word maidan is of Arabic origin and was adopted by Ukrainians from the Ottoman Empire. Other well-known Ukrainian words are borshch – traditional Ukrainian soup or the version of the same word that came to English via Yiddish as borsht; Cossack or, more natively, Kozak – a member of Zaporozhian Host; and pysanka – a decorated Easter egg.

What are the connections of the Ukrainian language to other languages of Europe and how had it interacted with other languages throughout its history?

First things first: genealogical relationship

Languages of Europe

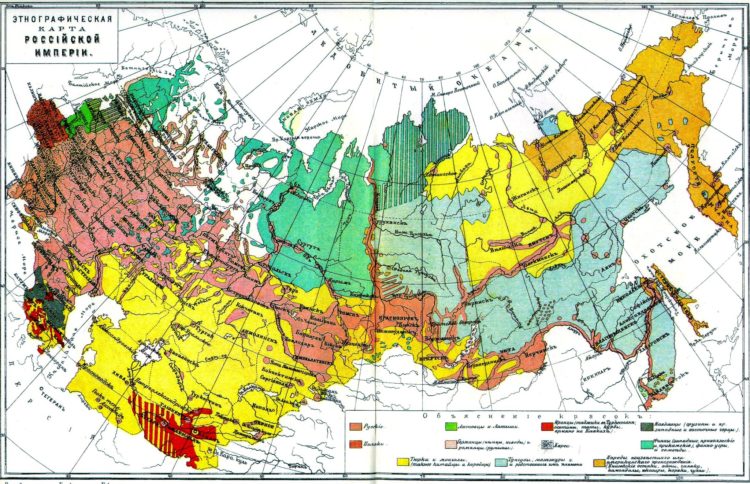

Besides Ukrainian, the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages includes Polish, Czech, Slovak, Slovene, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Belarusian, Russian, Upper and Lower Sorbian languages in Germany, varieties of Serbo-Croatian, dead Old Church Slavonic, and up to a score more languages depending on the inclusion of other extinct languages and considering the varieties such as Silesian, Rusyn, Prekmurje Slovene as languages of dialects.

Europe’s modern Indo-European languages include Germanic languages such as English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic; Romance languages such as Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, Romanian, Portuguese, Catalan, Sicilian; Celtic such as Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, Breton; Baltic languages which include Lithuanian and Latvian; Greek, Albanian, and Armenian are the only major representatives of their own separate branches within the modern Indo-European languages.

Major non-Indo-European languages of Europe are Finnish, Hungarian, Basque, and also various Turkic and North-Caucasian languages, Maltese language of Semitic origin, and Cypriot Arabic. These come from other language families and have their own unique histories.

The origin of Indo-Europeans

Other theories suggest that Proto-Indo-Europeans originated in Anatolia (modern Türkiye), Caucasus, or India. Whatever is the place of origin, it is still impossible to make any substantiated suggestion as to where the proto-Indo-Europeans could have arrived from and what languages they could have spoken before PIE emerged.

Every language, unless it’s isolated geographically or dead, interacts with neighboring languages throughout its entire history, exchanging words, grammar and pronunciation features.

The history of Ukraine has been turbulent throughout its entirety, so Ukrainians and their ancestors didn’t lack interactions with various peoples and languages in the course of separating Slavs from other Indo-Europeans and further formation of the Ukrainian language.

Here we’ll take a glimpse at some of the interactions of Ukrainian, Old Ukrainian, and earlier Common Slavic with neighboring languages starting from modern times, back to Kozak state, further back to medieval Rus up to antiquity. For the sake of a better comfort reading experience, we use English transliteration for Ukrainian words in this article.

Ukrainianisms in other languages

Together with the maidan, borshch, Cossack, and pysanka mentioned above, most of the Ukrainian words that made their way to other languages are related to Ukrainian culture, history, ethnic, or geographic terms.

With borshch, culinary terms also include horilka ‘Ukrainian vodka,’ kasha ‘porridge,’ holubtsi ‘cabbage rolls,’ varenyky ‘dumplings,’ syrnyky ‘quark cheese pancakes.’

With Cossack, historic terms include hetman ‘highest military officer,’ Sich ‘administrative and military center of the Zaporozhian Cossacks.’ The words boyar ‘nobleman in Eastern Europe in the 10th-17th centuries’ (Ukrainian boyaryn) and knyaz ‘prince, duke, count’ date back to Kyivan Rus times. Knyaz, by the way, has its roots in proto-Germanic or in Gothic, but let’s talk about Goths later.

With pysanka, culture-related terms include bandura ‘a traditional stringed instrument,’ sopilka ‘recorder,’ hopak ‘Ukrainian dance,’ vyshyvanka ‘traditional embroidered shirt.’

Not so general examples of the words of Ukrainian origin in neighboring modern languages are mentioned below.

Influences on Ukrainian in modern times and in recent centuries

As English has been the world’s lingua franca or the de-facto language of international communication since the 20th century, most of the loanwords nowadays come to Ukrainian from or via English. Examples of such words are menedzher ‘manager,’ biznes ‘business,’ kompyuter ‘computer,’ samit ‘summit (meeting),’ pled ‘plaid’, and so on and so forth.

From the 18th to the late 20th century, Russian borrowings were heavily forced into Ukrainian so that many native Ukrainian words came out of use and were replaced by Russian vocabulary. In this time period, most of the Ukrainian lands were under the rule of the Russian Empire and then its successor – the Soviet Union. The Russian Empire considered Ukrainian a dialect of Russian, attempting to hijack Ukrainian history and eliminate the Ukrainian language by assimilating Ukrainians.

The Soviet Union continued the colonial policies, although recognized the existence of Ukrainian yet tried to make the language as closer to Russian as possible while retaining the status of Russian as the language of prestige across the empire. And Russia partly succeeded as many Ukrainian became primarily Russian-speaking, even if their first language is still Ukrainian, they can speak Russian as their second language. Examples of Russian loanwords in Ukrainian are chynovnyk ‘an official,’ ukaz ‘decree,’ pikhota ‘infantry,’ liotchyk ‘pilot,’ kopiyka ‘copeck.’

Otherwise, together with “standard” Ukraine-related vocabulary, Russian borrowed multiple Ukrainian words mostly as colloquial, for example, devchata ‘girls,’ torba ‘bag,’ shkoliar ‘schoolboy,’ malevat’ ‘to draw,’ khleborob ‘grain grower.’

Mostly Latin– and Greek-based international scientific and political terms that came to Ukrainian from French, English, German and other languages in this period were also borrowed via Russian. Among those are Latinisms student, lektsiya ‘lecture,’ konsultatsiya ‘consultation,’ sufiks ‘suffiks,’ sinus, konus ‘cone,’ inyektsiya ‘injection,’ retsept ‘recipe,’ generator, turbina ‘turbine,’ natsiya ‘nation,’ dyktatura ‘dictatorship,’ variatsia ‘variation,’ etc. Relevant Greek-based words are polius ‘pole,’ klimat ‘climate,’ biolohiya ‘biology,’ ekonomiya ‘economy,’ azot ‘nitrogen.’

Somewhere around this period or earlier, Ukraine borrowed a number of German words, such as dakh ‘roof,’ druk ‘printing,’ tsement ‘cement,’ shryft ‘font.’ They could have come directly from German or via Polish. The word shakhray ‘swindler, con man’ also comes from German via Polish or Yiddish. And the Ukrainian gvalt ‘uproar’ related to German Gewalt came definitely from Yiddish.

Some French words made it into Ukrainian as well, such as makiyazh ‘make-up,’ parfum ‘perfume,’ bulion ‘broth,’ pliazh ‘beach,’ and some other, including those that got into Ukrainian via other languages, like servetka ‘napkin’ from French serviette via Polish.

Between Kyivan Rus and annexation by Russian empire (13-17th c.)

In this period Ukrainian fully formed as a spoken language, developing most of its distinctive features to re-emerge as a literary language sometime later.

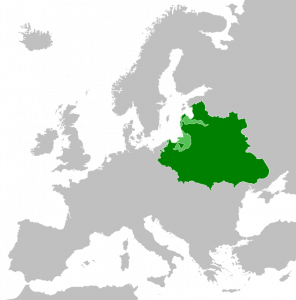

Large parts of future Ukraine found themselves in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, while other parts of Ukraine were under Russian control, although weren’t merged into the Russian Empire yet. In this period, the Ukrainian language was most influenced by Polish, the main language of the Commonwealth.

Polish borrowings – Polonisms – are the second largest group of loanwords in Ukrainian. Examples of those are vlada ‘political power,’ koshtuvaty ‘to cost’ (from German via Polish), rakhunok ‘account,’ mits’ ‘strength,’ promin’ ‘ray,’ chesnota ‘virtue,’ uvaha ‘attention.’

As Ukrainians lived near and alongside Poles for many centuries, the borrowing worked the other way as well, some Ukrainian words made it to Polish, for example, the Polish words hreczka ‘buckwheat,’ hodować ‘to feed,’ czereśnia ‘sweet cherry,’ mowa ‘language (archaic),’ serce ‘heart (instead of Old Polish sierce)’ and others origin in Ukrainian.

Polish also became the mediator language for many German borrowings in Ukrainian at this period. The Ukrainian words dyakuyu ‘thanks,’ ganok ‘porch,’ pliashka ‘bottle’ (and then the same Polish word came via Russian as fliazhka ‘flask’) are the examples of such German-via-Polish borrowings.

A wave of Greek and Latin borrowings came – mostly via Polish – in the Ukrainian language in the 15-17th centuries as these two classic languages were taught in schools. Some of the Greek terms of this period in Ukrainian are absurd, hramatyka ‘grammar,’ istoriya ‘history,’ matematyka ‘maths,’ biblioteka ‘library,’ teatr ‘theater,’ khor ‘choir.’ Latin words dating back to this period are amator ‘amateur,’ humor, herb ‘coat of arms,’ kalendar ‘calendar,’ konstytutsiya ‘constitution,’ material, okuliary ‘glasses,’ orenda ‘rent,’ termin ‘term, time period.’

In this period, Ukrainian also borrowed a number of Turkic words, many of which were related to chumak (wagon-based traders) and kozak life. Both words chumak and kozak are themselves of Turkic origin. Other examples of Turkisms from this period are tiutiun ‘tobacco,’ shatro ‘large tent,’ tovarysh ‘companion, friend,’ osavul ‘an administrative official,’ kochuvaty ‘nomadize, migrate,’ kavun ‘water-melon,’ otara ‘flock of sheep,’ kish ‘the central body of government in Zaporozhian Sich.’

The Romanian language borrowed Ukrainian words such as hrişcă ‘buckwheat,’ hulub ‘pigeon,’ lan ‘arable field,’ while Ukrainian borrowed Romanian words brynza ‘type of cheese,’ mamaluha ‘cornmeal gruel’ and other terms related to Romanian culture.

Also around these times, non-Indo-European Uralic Hungarian language exchanged some words with Ukrainian, borrowing such words as kocsan ‘corncob’ and kocserha ‘fire iron’, and returning back the words gazda ‘householder,’ huliash ‘goulash’ and others.

Kyivan Rus

Somewhere around this period or earlier first distinctive features of Ukrainian, such as fricative h as a replacement for g sound started to emerge in the Slavic dialects that later split into Ukrainian and Belarusian languages.

A lot of Greek words came to Old Ukrainian with the Christianization of Kyivan Rus in 988. Among those were not only religious terms such as yanhol ‘angel,’ apostol ‘apostle,’ Bibliya ‘Bible,’ vivtar ‘altar,’ ikona ‘icon,’ idol ‘idle,’ palamar ‘sexton’; but also a great number of Christian names like Anatoliy, Andriy, Vasyl, Oleksandr, Iryna, Halina, Kateryna, Olena. Some Latin names came as well, such as Valeriy, Viktor, Viraliy, Serhiy, Viktoria, Maryna, Natalia. Since then, the Greek-dominated set of Christian names displaced most of the old Rus’ names.

Another notorious change was the usage of the Old Church Slavonic language, which is related to the South Slavic Bulgarian language and was developed for translating Christian literature from Greek. Most of the Greek words borrowed at the time came via Slavonic, which also brought a number of South Slavic terms to Old Ukrainian, such as blaho ‘good, welfare,’ oblast ‘region, province,’ rab ‘slave,’ nuzhda ‘indigence,’ sviashchenyk ‘priest,’ uchytel ‘teacher.’

The Mongol invasion in the 13th century that subsequently brought to de-facto demise of Kyivan Rus brought not so many words in Ukrainian, rare examples are teliha ‘cart’ and korohva ‘gonfalon.’ Moreover, these two words were probably borrowed earlier as they might have been brought by the Huns in the 4th century.

Pre-Kyivan Rus times and antiquity

Among the earliest borrowings from Turkic languages were losha ‘foal,’ sahaydak ‘quiver,’ karyi ‘dark brown (eyes)’ which came due to the contacts with Polovtsy and Pechenegs and other Turkic tribes that lived in modern Ukrainian steppes at the times.

The earliest borrowings from Greek came via direct Slavic contacts with colonists in Greek cities on the Black Sea coast and in Crimea, as well as via other languages. Several examples of the early borrowings from Greek are kyt ‘whale,’ korabel ‘ship,’ myata ‘mint,’ ohirok ‘cucumber,’ troyanda ‘rose flower,’ myska ‘bowl,’ parus ‘sale,’ lyman ‘estuary,’ vyshnia ‘cherry.’

Due to rare contacts with Romans, eastern Slavs didn’t have a lot of early borrowings from Latin, rare Latinisms are koliada ‘carol’ from Latin kalendae ‘first day of the month,’ and later kesar ‘caesar,’ and fortuna ‘luck.’

Meanwhile, the Medieval Latin word sclāvus ‘slave’ derived from Byzantine Greek Σκλάβος ‘Slav’ (after Sklavins, the name of one of the Slavic tribes). The late Latin word emerged as Slavs were often targeted in the early Middle Ages for enslaving by conquering peoples.

‘Not that modern parody, the real Goths’

The Proto-Slavic common language started to collapse around the 4th century. So most of the developments before this date, including borrowings, are shared by most of the Slavic languages.

In the 2nd century CE, Germanic Goth tribes expanded to the Black Sea steppes and dominated there for at least two centuries until the Hun invasion. Goths spoke Gothic, a now-extinct East Germanic language. Based on the language material, linguists believe that the common Slavic word for bread – which is khlib in Ukrainian – was borrowed from Gothic hlaifs. This doesn’t necessarily mean that prior to the 2-4th centuries Slavs didn’t bake bread as the word could initially mean some particular kind of bread and then become a common term.

Other examples of the borrowings from Gothic are shchyryi ‘sincere/honest’, sprytnyi ‘agile’, gley ‘mucilage’ – these are common to both Belarusian and Ukrainian but are unknown in the Russian language, “which means that the dialects from which it later developed did not yet exist,” says Prof. Kostiantyn Tyshchenko from Kyiv.

Other Gothic words that became common Slavic are sklo ‘glass’ from Gothic stikls ‘goblet’; kotel ‘cauldron’ from Gothic katils. The word tserkva ‘church’ is a pra-Slavic borrowing from Germanic laguages related to the modern German Kirche has allegedly came from Gothic as well.

Going deeper: Celtic and Iranian borrowings

In their prime as of 275 BC, Celtic tribes spanned across most of Europe from the Atlantic up to the west of modern Ukraine, while the Western Scythians, generally believed to have been of Iranian origin, dominated the Pontic steppe at the time. Unfortunately, both didn’t leave behind any written documents in the territory of modern Ukraine, however, traces of their languages retained in the Ukrainian toponymics – names of the places.

For example, the name of the small river Radorobel in Zhytomyr Oblast is of Celtic descent meaning ‘one having rapids’ while Ukraine’s largest river – Dnipro/Dnieper bears the Scythian name known via Greek sources as Δανάπρις which means ‘deep water.’ In total, some 200 geographic names in Ukraine are believed to be of Celtic origin.

Some linguists argue that the Ukrainian word motyka ‘mattock’ is borrowed from Celtic, maybe via Germanic languages. Meanwhile, the Old Slavic word vladyka ‘lord, sovereign, archbishop’ now mostly used in its religious meaning has a Celtic parallel, particularly Welsh gwledych ‘kingdom, government, reign, ruler‘. Welsh gwlad means ‘country, land, region,’ meanwhile the Slavic word is generally believed to be derived from vlada ‘(political) power’ so the words seem to be native in both language groups, nevertheless, the Slavic term could have emerged by adapting the foreign term based on the native lexical resources.

Researcher Václav Blažek draws parallels between Old Irish deity Dagdae (Celtic *dago-dēuo- ‘good god’) and Slavic god Dazhboh (from *Dadjьbogъ “God give”).

Iranian languages, such as Sarmatian and later Scythian brought into Slavic languages the words Boh ‘God,’ sviatyi ‘holy,’ ray ‘paradise.’ Other examples are the words pan ‘mister’, dbaty ‘to take care,’ bachyty ‘see,’ tryvaty ‘to last,’ zhvavyi ‘vivid,’ kat ‘executioner’ – these are common in Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Polish. The word khata ‘hut, small house’ of the Iranian origin is common for Ukrainian and Belarusian, other Slavic languages borrowed it later from Ukrainian with the meaning ‘traditional Ukrainian hut.’

As in the first centuries AD, ancestors of Ukrainians lost direct language contacts with Iranian peoples, later additions from Iranian languages came into Ukrainian in recent centuries via Turkic languages. For example, terezy ‘scales,’ sharovary ‘wide trousers.’

This publication is part of the Ukraine Explained series, which is aimed at telling the truth about Ukraine’s successes to the world. It is produced with the support of the National Democratic Institute in cooperation with the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, Internews, StopFake, and Texty.org.ua. Content is produced independently of the NDI and may or may not reflect the position of the Institute. Learn more about the project here.

Related:

- Ukraine creates free online courses of Ukrainian language for foreigners

- Language protection: what Ukraine can learn from three European countries

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

- Ukrainian history gift to global history – Prof. Snyder

- Russia’s war against the Ukrainian language

- Ukrainian Institute launches first-ever English-language online course about Ukraine

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments