And yet, the “bandits” won over the heart of the European royal, who later took an oath to the Ukrainian people and led a life worthy of an adventure novel, earning his second name — Vasyl Vyshyvany, after the Ukrainian vyshyvanka shirt that he wore under his military uniform, choosing a life of political activism and struggle over the carefree existence of royalty.

His story, in all its tragedy, is also a sign of hope: it serves as a reminder that the love story between Ukraine and Europe goes both ways. Not only has Ukraine been in love with Europe, but Europe has more than once fallen in love with Ukraine.

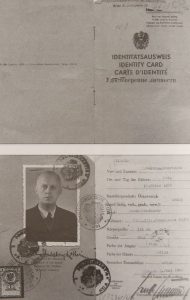

The great Habsburg of Ukrainian history was born on February 10, 1895 on the island of Lošinj (present-day Croatia), on the family estate of his father Archduke Karl Stephan Habsburg (during his arrest by the Soviet authorities, he indicated Pola, Italy — today Pula, Croatia — as his place of birth).

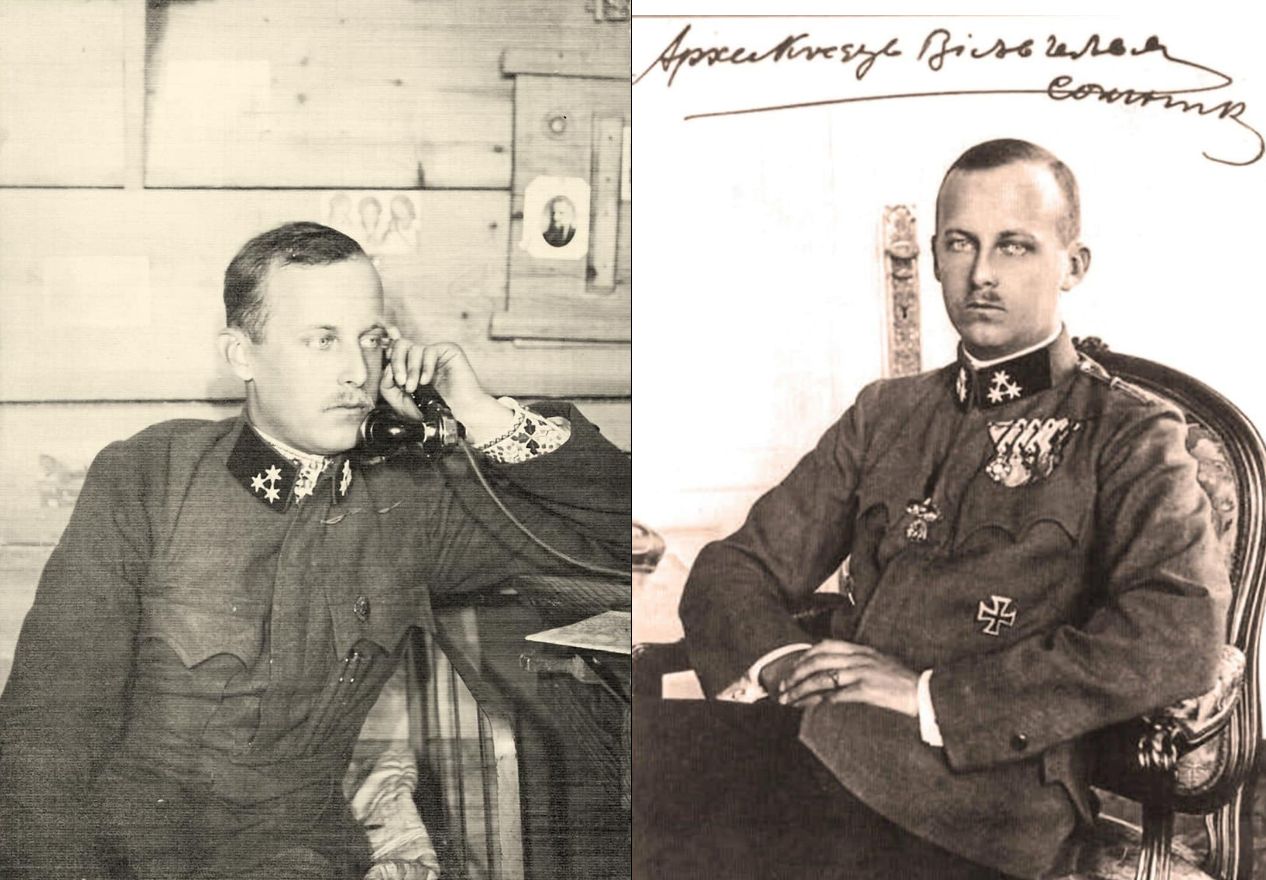

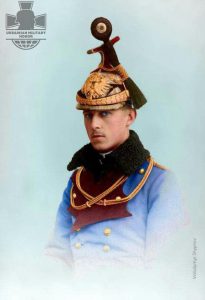

His name was Archduke Wilhelm Franz of Austria-Teschen, also known as Wilhelm Franz von Habsburg-Lothringen and later as Vasyl Vyshyvany, a colonel of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Sichovi Striltsi), a politician, diplomat, poet and dreamer. Wilhelm was a distinguished member of the Royal House of Habsburg-Lorraine, a branch of which gave the world several Austrian kings and emperors, including Emperor Franz Josef, who was Wilhelm’s uncle twice removed. At different times, the Habsburgs ruled a greater part of Europe – Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Bohemia, Western Ukraine, and Hungary.[/box]

Wilhelm was born and lived in an extraordinary period of European history, when the old order of the past was giving way to an undefined future, when rival nationalisms were emerging throughout the Empire, when European borders were fluctuating, when everything, including identity itself, seemed ready for change.

Wilhelm’s life is strongly reminiscent of a true adventure novel. As we follow him from his young years at the parental estate in the Polish city of Zywiec, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, to his tragic death in a prison hospital in Kyiv, we cannot but wonder why and how a prominent European royal would fall in love with Ukraine and choose a life of political activism and struggle over a carefree aristocratic existence and the privileges of royalty.

Early years

Archduke Wilhelm was the youngest son of Archduke Karl Stephan and Archduchess Maria Theresa, Princess of Tuscany. Karl Stephan and his family resided at the Castle of Saysbusch (Zywiec) in Galicia (today’s Halychyna, Ukraine, a crown land of Austria-Hungary which straddled the modern-day border between Poland and Ukraine). Archduke Karl Stephan was considered a serious candidate to be regent and eventually king of a future Poland.

Although Wilhelm was born in a distant land – on a family estate on Losinj Island (present day Croatia), he grew up on the parental estate in Zywiec and was daily exposed to Polish culture and traditions.

Wilhelm’s father, Archduke Karl Stephan, loved his adopted land – Poland, and although there was no independent Polish state in the early 20th century, he was able to combine his loyalty to the Habsburg monarchy with his love of Poland. He decided that his children would adopt a Polish identity and study the Polish language.

However, Archduke Karl Stephan was not very fond of the Ukrainians who populated certain regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; he viewed them as unruly peasants and rough-and-tumble bandits vying for a free Galicia (Halychyna). In fact, the whole family was contemptuous of Ukrainians and spoke scornfully of the “wild and unruly bandits” living in the Carpathians.

Early travels to Hutsulshchyna – the land of the free

Young Wilhelm was intrigued by his father’s tales of this “rogue tribe” of Ukrainian mountaineers and rebelled at his family “Polishness”. In 1912, at the young age of 17, he decided to see for himself and set out for Western Ukraine in search of these mysterious Ukrainians. He boarded a train and traveled incognito to Vorokhta, then Zhabye (now Verkhovyna), through several Hutsul villages in the Carpathian Mountains, and stayed with local families. He did not see anything particularly “wild” about these people, but he fell in love with their culture and language.

Indeed, it was during these travels that he developed a strong feeling and passionate attraction to Ukrainian culture and spirit, a sentiment that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

“I first heard about Ukrainians [on the family estate in Zywiec]. The Poles called them ‘Rusyns’ and spoke of them as thugs and bandits. I truly believed that the Ukrainians who lived so close to Zywiec were wild rogues.

When I turned 17, I was able to arrange a journey to the Hutsul mountains. I travelled through Lviv and Stanislaviv [now Ivano-Frankivsk] incognito. I was impressed by the beauty of the Hutsul mountains… I met a Hutsul peasant in Vorokhta and I stayed with him for a while. I traveled far and wide, searching high and low for those Ukrainian thugs and bandits. In vain… I was disappointed. I returned to Zywiec a changed man,” he wrote.

World War I

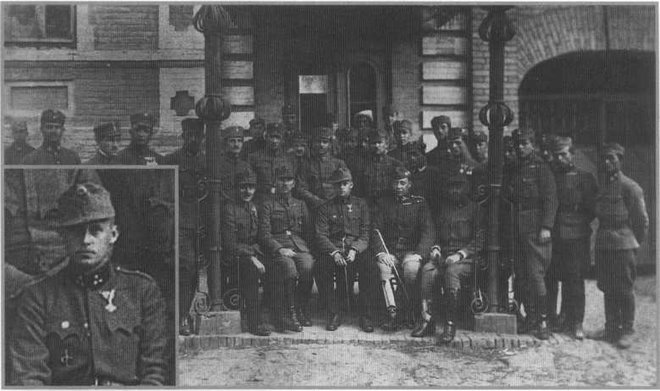

During the early war years, Wilhelm studied at the Vienna Military College. He graduated in 1915, and was deployed to the frontlines with a platoon (sotnya) of the 13th Galician Lance Regiment, 55% of which was composed of Ukrainians, primarily from Zolochiv region (today, in Lviv Oblast). The recruits mainly spoke Ukrainian and introduced the young Austrian prince to such notable Ukrainian literary figures as historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, writer Ivan Franko, poet and bard Taras Shevchenko, and many others.

“I learned to read Ukrainian in the winter of 1915. I was taught by soldier Prymak from Ternopil region. My first book in Ukrainian was a short history of Ukraine by Hrushevsky. I also read many poems by Ivan Franko. His writing is most impressive, especially ‘The Stonecutters’ (Kamenyari). I also enjoyed stories by Fedkovych and Stefanyk, while Hnat Khotkevych’s ‘Stone Soul’ had a special meaning for me, because I love the Hutsul mountains!… Of course, I read Shevchenko with passion, as well as all literature related to the Sich Riflemen.”

Archduke Wilhelm admired his men, and often spoke of and wrote about their courage and military prowess. Constantly surrounded by Ukrainians, his acute Austrian mind caught all their virtues and flaws, recording them daily in his memoirs.

“My regiment was composed of Ukrainians who all had a strong national identity, but were afraid to reveal it, because every Ukrainian was considered a political suspect. Almost all the officers were German. Ukrainians were so afraid of being persecuted that many of them identified themselves as Poles. I admonished them for this, and told them that if I acknowledge the Ukrainian nation, they should also. The fighters in my sotnya have high moral values and are fantastic fighters. I truly believe that Ukrainians make the best soldiers. But, they’re a bit like sheep: if they trust and believe in their commander, they will go through hell and high water and do the impossible,” writes Vasyl Vyshyvany

And further, Vasyl speaks of the courage and steadfastness that he so often observed in Ukrainian soldiers during combat.

“I will say one more thing about the Ukrainian soldier: he has the nerves of steel required of a good soldier. Here’s one example: in the autumn of 1917, we lay in the trenches near the village of Kadubysk (Brody County). It was quite peaceful. Suddenly, the moskali began firing. A grenade fell into the trenches between two Ukrainian soldiers. No explosion. Well, there aren’t many people who wouldn’t jump away from such a ‘gift’ by an enemy. But, both soldiers only cursed loudly and remained in the trench… I could tell you many stories! In a few words, I believe the Ukrainian soldier is the best in the world!

Ukrainians soldiers can go hungry, work very hard and endure all kinds of hardship… There are no better soldiers to launch an offensive than the Ukrainians. They rush forward so eagerly that sometimes they get out of hand. But, they’re not very good in defensive positions (Prussian Germans are the best). The Ukrainian soldier’s weakest point is his lack of initiative, but he is ready to execute any command. He also has a good sense of direction… even at night. If the commanding officer cares for his men, the Ukrainian soldier will be faithful and true even to death.”

Wilhelm’s soldiers loved their commander and gave him as an exclusive gift – a Ukrainian embroidered shirt (vyshyvanka), which he always wore under his uniform. It was during these years that young Wilhelm asked his soldiers to call him Vasyl, and later, he was given the surname Vyshyvany (Embroidered).

Wilhelm’s men were encouraged to wear blue-and-yellow armbands, the Ukrainian national colours. This infuriated the Poles, who came to regard Wilhelm as a dangerous socialist subversive, calling him the “Red Prince”.

“My sotnya, which consisted only of Ukrainians (I got rid of the Poles), was called ‘red’ or ‘socialist’, and I was called the ‘Red Prince’. Of course, I was branded a socialist not because I was spreading socialism, but because I demanded that every Cossack in my unit wear a Ukrainian blue-and-yellow insignia, which was seen as treason in Austria, because all Ukrainians were viewed as Russophiles…”

Discovering the land of the Cossacks

In September 1917, Vasyl Vyshyvany arrived in Lviv, where he welcomed and befriended Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, who had just returned from Russian captivity. They became good friends and worked closely on Ukrainian issues. Sheptytsky saw the young Habsburg as a leader of the Ukrainian monarchical movement and the main contender for the throne.

During this period, Vasyl also served as a liaison between Ukrainian community leaders and Karl Josef’s successor, Emperor Karl I of Austria, pushing the ‘Ukrainian issue’ and the creation of an autonomous Grand Duchy of Ukraine, which was to include all the territories of Galicia and Bukovyna, as well as the Ukrainian lands ruled by Imperial Russia, which had to be re-conquered.

With the disintegration of the Russian Empire, the chaos of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the emergence of the Ukrainian National Republic on 25 January 1918, and the signing of the Beresteisky Treaty on 9 February, 1918, whereby the Central Powers (German Empire, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria) declared Ukraine’s sovereignty in return for food support (in German ‘Brottfrieden’ – peace for bread), the political and geographical map of Europe began to change.

Emperor Karl I of Austria placed his young cousin Vasyl Vyshyvany in charge of the ‘Battle Group Archduke Wilhelm’ (Ukrainian soldiers and officers from the Austrian Legion of Sich Riflemen) and sent him first to Odesa, then Kherson and Zaporizhzhia to fight the Bolsheviks. It is here, in the Cossack homeland that Vasyl Vyshyvany found his place and mission. He began to ‘Ukrainize’ the territories, spreading the message of national liberation.

On May 22, 1918, UNR colonel Petro Bolbochan’s Cossack regiment and Vasyl Vyshyvany’s Sich Riflemen met to honour and celebrate the Day of the Holy Trinity (Pentecost) in Velyky Luh (Great Meadow) of Zaporizhzhia.

“Our hearts and souls burn with a lovely, bright, uncontrollable flame of pride and joy on the occasion of May 22, here in Velyky Luh…

The village starshyna [elder] arrives. He greets the Prince, the Galician Ukrainian Sich army, Otaman Bolbochan and all of free Ukraine with bread and salt, and sincere and burning words of joy. The Prince responds in Ukrainian, shaking hands with the villagers, and suddenly cries of joy rise from the crowd as a huge human wave sweeps us and my men into this huge, lush garden…” recalls Vasyl Vyshyvany in his memoirs.

Vasyl’s troops occupied a small area near the site of the old Zaporozhian Sich, and were tasked with disseminating the Ukrainian national cause in any way possible. Vasyl mixed easily with the local peasants, allowing them to keep the lands that they had taken from the landlords in 1917.

He also prevented the Habsburg armed forces from requisitioning grain from the peasants. Ukrainians who had resisted requisitioning elsewhere were given refuge in Vasyl’s territory. These actions outraged Germany and Austrian officials in Kyiv, but increased Vasyl’s popularity among local Ukrainians, who referred to him affectionately as ‘Kniaz Vasyl’ (Prince Vasyl).

In the autumn of 1918, Vasyl Vyshyvany’s command was transferred from Zaporizhzhia to Bukovyna. During 1919, he served as colonel in the war ministry of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR).

The end of WWI and self-imposed exile

Within a year, Germany and Austria had lost the war, and events were moving at a fast pace. At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, no one was interested in Ukraine… and monarchs, actual or prospective, were out of fashion. At a meeting of the Big Five (France, Britain, Italy, the USA and Japan) on 16 January, Lloyd George called Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura an adventurer and dismissed Ukraine as an anti-Bolshevik stronghold.

“I only saw a Ukrainian once. It’s the last Ukrainian I have seen, and I’m not sure that I want to see any more.” declared Lloyd George

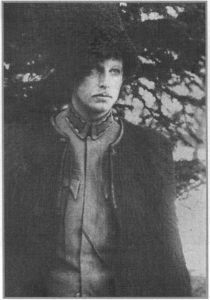

After the defeat of the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1921, Ukraine was once again partitioned, this time between Poland and the Soviet Union. In protest at the Treaty of Warsaw in 1920 (Symon Petliura’s military-economic alliance with Josef Pilsudski), Vasyl Vyshyvany resigned and began the life of exile, first in Vienna, followed by sojourns in Spain and Paris. Wherever he went, Vasyl became involved with Ukrainian émigré circles and searched for funds to support his Ukrainian campaign.

In Vienna, Vasyl founded the Ukrainian Free Cossack Society and headed the General Board, which published the weekly Soborna Ukraina.

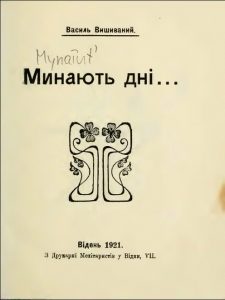

In 1921, Vasyl Vyshyvany published a collection of poems in Ukrainian, Mynayut Dni (Минають дні – The passing days), dedicated to the “Fighters who fell for the freedom of Ukraine”.

The collection consists of 23 poems, which, according to writer and literary critic Yuriy Khorunzhy, are heavily influenced by Taras Shevchenko, Oleksandr Oles, Hryhoriy Chuprynka, Spyrydon Cherkasenko and the authors of Sich Riflemen songs.

“Gone are the days of exuberant love,

Gone are the days of sorrow,

Gone are the days of grievous suffering,

And our long and arduous struggle…”

In Paris, Vasyl Vyshyvany maintained close ties with the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO), the newly-formed Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, mainly with OUN leader Yevhen Konovalets, and corresponded regularly with Dmytro Dontsov, Ukrainian writer, political journalist, and theorist.

For a brief spell during the turbulent years of World War II, Vasyl felt that Nazi Germany might help him in his quest for the leadership of Ukraine, but he soon realized that Hitler would never recognize an independent Ukraine. After he and his brother Karl Albrecht were arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo, Vasyl saw the error of his ways, joined the local anti-Nazi resistance in Vienna and moved closer to the Ukrainian Banderite movement. By 1942, he was spying for some intelligence services, possibly the British SIS which financed and supported resistance movements throughout Europe. Eventually he became a spy for the French Resistance against the Nazis and then the Soviet Union.

Arrest and death in Kyiv

In 26 August, 1947, Vasyl Vyshyvany was kidnapped on the streets of Vienna by the Soviet secret service SMERSH and MGB. He was accused of espionage with Western powers (cooperating with English and French counterintelligence) and of links with the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). A year later, the Soviet authorities decided to transfer him to Lukyanivska Prison in Kyiv.

Ukrainian SBU archives give a detailed account of Vasyl’s interrogation. At one point, prison director Zhuravliov addresses him curtly:

“So, you call yourself Vasyl Vyshyvany? Tell me who you really are. If you are an Austrian, a foreigner, we will treat you as a foreigner, but if you’re Ukrainian, you understand very well how you will be treated…”

Vasyl Vyshyvany answers firmly and resolutely:

“I am a citizen of the Ukrainian National Republic, a colonel in the UNR Army and the Ukrainian Galician Army. I took the Oath to the Ukrainian people. My native language is Ukrainian.”

The investigation was completed in April 1948, and Vasyl Vyshyvany was sentenced to 25 years in the Soviet Gulag. He never made it to the penal colony… on 1 July, he was transported, feverish, delirious and hemorrhaging profusely, to Lukyanivska Prison Hospital. On 18 August 1948, Archduke Wilhelm of Habsburg, aka Vasyl Vyshyvany died a broken man, ill and alone in a Soviet prison hospital.

But, a question remains… Why did the Soviet regime abduct and imprison a foreign royal, a fallen prince and a ‘leftover’ of the old empire?

The post-war period saw the USSR “cleansing” Europe of prominent Ukrainian and Russian figures (Ukrainian writer and theorist Lev Rebet assassinated on 12 October, 1957 in Munich; political leader Stepan Bandera assassinated on 15 October 1959 in Munich) and public opinion leaders in the countries of the future Warsaw Pact. Thus, an information vacuum was created, and the USSR could expand its spheres of influence, undermining world democracy.

For the Bolsheviks and the KGB, Wilhelm von Habsburg was a dangerous name, because he was a living thread between a potential Ukrainian revival and the ‘New World Order’ after World War I.

National tributes and European legacy

Until the very end, Vasyl Vyshyvany considered himself Ukrainian and dreamt of a free and united Ukraine within Europe. In his memoirs, he clearly stated his purpose in life:

“… I want to work for Ukraine, and I shall continue working as long as I can…

In my report, I openly stated that I feel Ukrainian and the interests of Ukraine come first.”

In his powerful poem To Arms!, Vasy Vyshyvany turns to his men and the Ukrainian nation, echoing a war cry that is more than relevant today.

To arms! To arms, my riflemen!

To save your native land!

Stand tall and strong like loyal Cossack sons,

And return home as Heroes!

Unfortunately, Vasyl Vyshyvany is virtually unknown in today’s Ukraine. For years, the Soviet Union systematically destroyed all evidence, all memory of Ukraine’s Heroes. And yet, Vasyl Vyshyvany representes an entire epoch of important European history, and his life reflects the story of the Ukrainian liberation movement and Ukraine’s European aspirations.

Vasyl Vyshyvany Square was inaugurated in Lviv in 1993. It lies in a quiet district of the city, with its unadorned stone plinth. The plinth was intended as the base for a monument, never completed, to the square’s namesake, a man of numerous identities, titles and nationalities.

On November 15, 2020, a plaque was unveiled on the facade of the old Austrian barracks, at the entrance to the Training Centre of the National Guard of Ukraine on Sichovykh Striltsiv Street in the town of Zolochiv, Lviv Oblast, where Archduke Wilhelm von Habsburg of Austria was stationed 105 years ago.

On 10 February, 2021, the project of a future monument to Vasyl Vyshyvany, created by sculptor Mykhailo Horlovy, was presented to the public. The monument will be inaugurated on 20 May, 2021 (Vyshyvanka Day) in a square at 39 Illienka Street, Lukianivka District in Kyiv. It will stand close to the planned monument of another Ukrainian Hero – Colonel Petro Bolbochan, the liberator of Crimea.

In a moving tribute to the ‘Red Prince’, the Ambassador of Ukraine to Austria Alexander Scherba stated:

“… This historical figure embodies all that is unusual, brilliant, passionate, and alive – from his first romantic trip incognito to Halychyna (Galicia) to his last sombre transfer to Soviet Ukraine. Not far from this place, in Lukyanivska Prison, he speaks his last words. In the face of death, he voices his name: Vasyl Vyshyvany. He answers questions in Ukrainian. He understands that these are his last days – and he, a royal born in Austria, desires to enter the other world, to appear before God… as a Ukrainian.

For all its tragedy, for us Ukrainians, this remarkable story is a bright sign of the future, a sign of hope. A reminder of a passionate love story between Ukraine and Europe. In fact, not only has Ukraine been in love with Europe, but Europe has more than once fallen in love with Ukraine. We Ukrainians must know these important pages of our history. The more we learn about the historical figure of Vasyl Vyshyvany, the more we can learn about ourselves. We are at the very beginning of this exciting journey. I’m convinced that Vasyl Vyshyvany will soon become the subject of books and operas, monuments and research, and maybe even TV series. We owe it to him and to ourselves. It is a debt of love.

WILHELMVS · FRANCISCVS · ARCHIDVX · AVSTRIÆ · ET · PVGNATOR · PRO · POPVLO · UCRAINÆ”

On the occasion of his 60th birthday on 11 January, 2021, Karl von Habsburg, grandson of the last Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl I, former European MP, a strong advocate of the Pan-Europa movement, and the head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, delivered a speech on the future of Europe, where he underlined the importance of Ukraine within the European community.

“…But we must also look to the East, where a country like Ukraine, with the Euromaidan, the Revolution of Dignity, as it is also known, has made it clear that the citizens of this country see their future in Europe and not under Russian dominance. No doubt there are still major problems in all of these countries, for example, in the areas of the rule of law and corruption, but they are European countries. Anyone who takes European unification seriously must make it possible for every European country to join the European Union. That is why I am also in favour of changing the current neighborhood policy towards Ukraine into a concrete policy on the prospect of membership.”

Since the 2014 Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine, there has been much talk and discussion about the country’s ‘Europeanness’, the European course and European integration. In truth, there is plenty of evidence that Ukraine’s place in Europe is not just a geographical concept. It is a strong determination which has its roots in history and is mentally ingrained in all Ukrainians.

Archduke Wilhelm von Habsburg, aka Vasyl Vyshyvany knew this, fought for this, but did not live to see his dream materialize.

A good read: Timothy Snyder’s The Red Prince (2008) is a captivating tale of the Habsburg dynasty during a turbulent period of European history dominated by emerging national identities and modern ideologies. The book focuses on the adventurous, glittering life of Archduke Wilhelm von Habsburg, the ‘Red Prince’, aka Vasyl Vyshyvany, who was a Habsburg royal, an officer in the Austrian army, a Ukrainian colonel, a playboy, a spy and would-be king of Ukraine. Timothy Snyder tells us that Archduke Wilhelm von Habsburg, Vasyl Vyshyvany, “wore the uniform of an Austrian officer, the court regalia of a Habsburg archduke, the simple suit of a Parisian exile, the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece, and, every so often, a dress. He could handle a sabre, a pistol, a rudder, or a golf club; he handled women by necessity and men for pleasure. He spoke the Italian of his archduchess mother, the German of his archduke father, the English of his British royal friends, the Polish of the country his father wished to rule, and the Ukrainian of the land he wished to rule himself.”