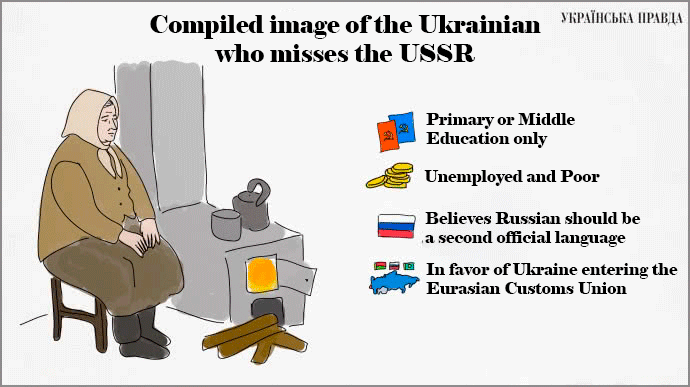

Ukrainska Pravda studied research from the Razumkov Center and the Rating Group, spoke with sociologists and historians, became familiar with their professional works and at last returned to compile an image of a Ukrainian who yearns for the USSR.

Does this have any logical explanation? And what is more threatening to the future of the country – a poor old woman from the village, or that Ukrainian who did not live a single day in Soviet times but still possesses Soviet values?

They are sad because they are poor

“The higher the level of education among people the less they miss the USSR. Therefore the ones who lost the most, miss it most,” explained Yaroslav Hrystak, a historian and Professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University. “This is, first of all, a desire to return to the times when ‘things were good.’ Generally, the longing to return to a ‘golden age’ is a global tendency.”

Statistics reinforce this: the older the individual and the lower his or her level of education and income, the greater the individual misses the Soviet Union. Nostalgia is greater among women (38%) than among men (31%). This is linked to the fact that in Ukraine women tend to live for 10 years longer than men.

In Hrytsak’s words, only a few miss the USSR for its ideology, but the majority misses it for “the stability.”

The majority of people’s regrets are linked to the perception that in Soviet times “there existed a certainty about tomorrow”, “a high level of social guarantees”, “free higher education”, “zero unemployment”, and “a sufficient level of material life.” Half of those who miss the Soviet Union also name as reasons the “perception of pride in a great state on the global scale”

and “the absence of armed conflict.”

It is clear that many of the aforementioned thoughts are subjective and arguable. But they are expected because they belong to people who today live in the villages, who do not travel, who have no access to any medical care, who are unable to take care of themselves, and who receive pensions paradoxically lower than what the amount of work they believe they put into them.

As long as the Russian Federation continues to associate itself with the Soviet Union, this portion of the population not only is disenchanted with Ukraine but has a pro-Russian outlook as well. For example, they desire Ukraine to enter Russia's Eurasian Customs Union, and that the Russian language became a state language or an official regional language.

There are no current data on who these “nostalgic” voters voted for in the presidential elections. The most recent data are from 2016. At that time they gave their support to the Opposition Bloc of Yuriy Boyko [the pro-Russian party which is the successor to ex-President Yanukovych's Party of Regions - ed.], to ex-Opposition Bloc MP Vadym Rabinovych or to Nadiya Savchenko, then only recently freed from Russia.

Sociologists remark that the political outlooks of people who miss the USSR are quite diverse. First, their outlooks depend on the region of residence. Second, in the thoughts of Danylo Sudyn, Docent of the Department of Sociology at the Ukrainian Catholic University, these people feel social deprivation and will be most strongly attracted to the party which promises the most.

Back in the USSR

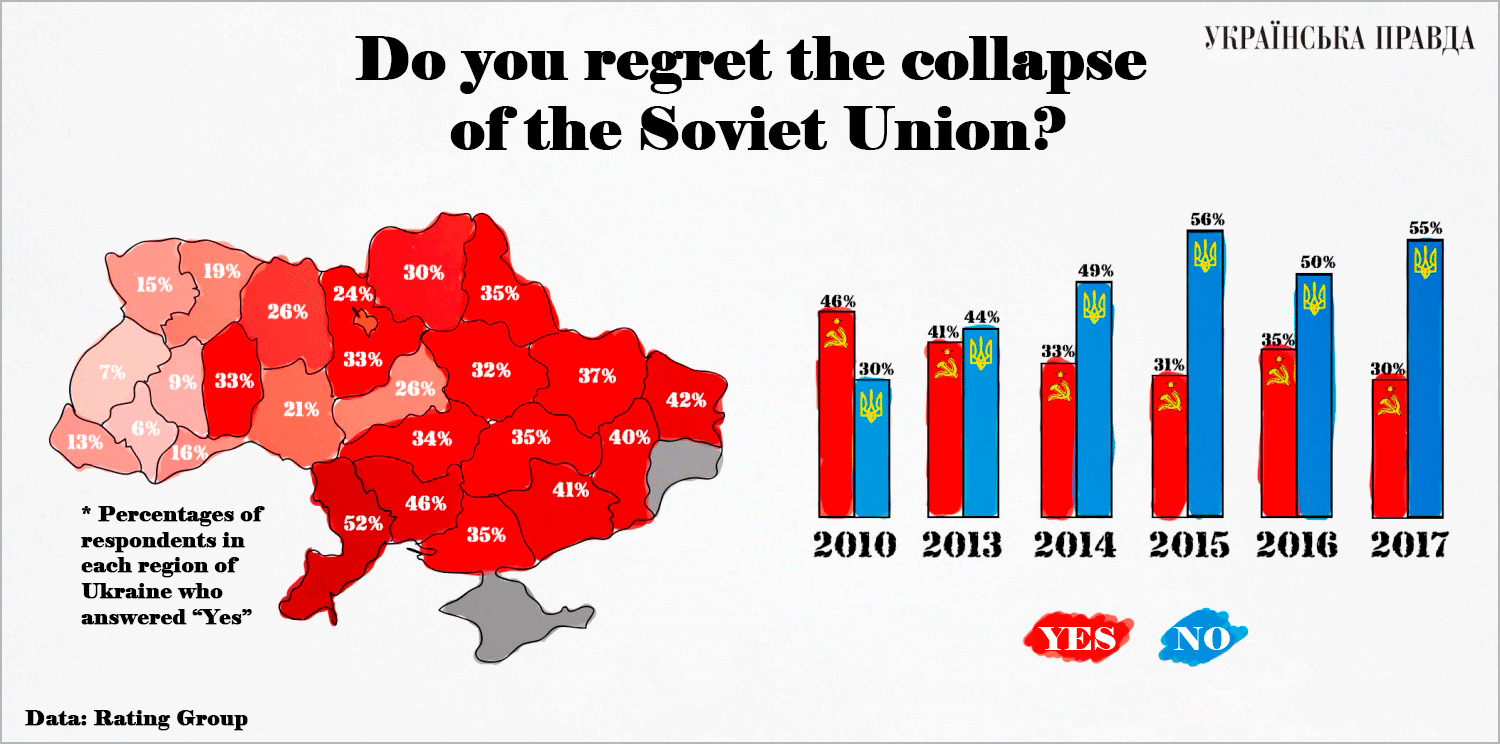

Today those nostalgic for the Soviet Union are four times more prevalent in eastern and southern Ukraine than in western Ukraine. If in the south and east their number has remained stable in the last few years – approximately 40% - then in the west and center, the number has declined substantially.

The majority of researchers are interested in the fact that the Soviet Union is missed by those people who never lived within it or almost can’t remember it. Thus, according to data from 2016, 14% of youth aged 18-29 years and 25% of those between 30 and 39 years are nostalgic for the USSR.

“This widespread phenomenon began to be recorded at the beginning of the 2000s. One of its markers is that they do not yearn for the Soviet Union, for its state structure, limitations, and deficits, but rather for the image of something which is the opposite of today’s world,” explained Danylo Sudyn.

“The ideology of the USSR was built on the ideas of equality and justice. Accordingly, that portion of the youth which does not perceive these in today’s society yearns for the idealized Soviet past.”

In Sudyn’s opinion, social inequality, which increased with the development of market relations in Ukraine, has not yet improved. In this light, the Soviet Union looks like a project which propagated an idea of equal possibilities and chances in life. The generation of youth, which is nostalgic for the past, has not thought about the limitations of these possibilities.

Soviet Man, or the Homo Sovieticus

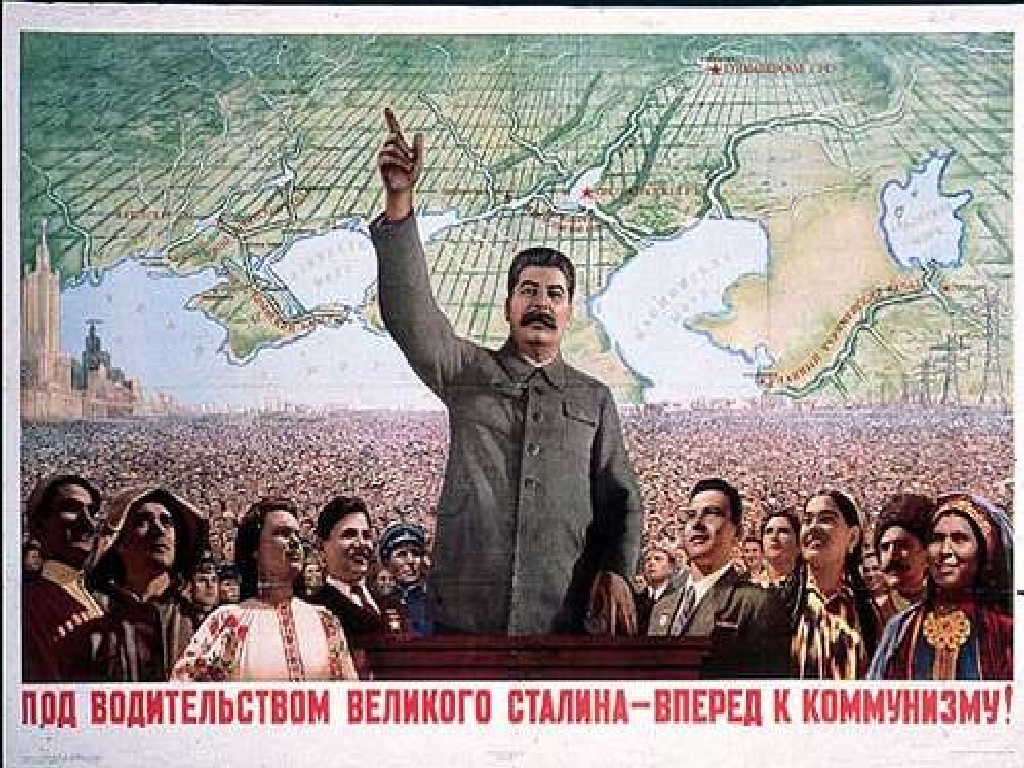

Researchers also compare nostalgia for the Soviet Union with grief over “a great father.”

For Ukraine, paternalism is an inherent political practice, in which the people are perceived as “children”

who need “fatherly care” from the authorities. And the population expects that the authorities themselves must change the country.

Statistics demonstrate this: 30% of Ukrainians desire a dictator to lead the country. However, they do not want one because they like tyranny, but rather they want a “Glorious Leader” who will fix everything himself.

Yaroslav Hrytsak cites evidence of this thesis: “40% of those who support Bandera at the same time have a positive view of Tsar Peter I [who initiated a reign of terror in Ukraine at the beginning of 18th century - ed.]. Ideology does not matter to people, only the personification of a strong hand.”

A similar mentality is for the most part inherent in Russia. 58% of the Russian population regret the collapse of the USSR and 78% consider that Russians require a “strong hand” at least some of the time, if not always.

People for whom a psychology of paternalism is inherent frequently evince other signs of “Soviet Man.” The idea even has its own sarcastic synonym: “Homo Sovieticus.” The phrase became well known in 1982 after the Soviet émigré sociologist Aleksandr Zinoviev published a book with that title. So long as the term does not have a single definition, the number of “Homo Sovietici” in post-Soviet countries is difficult to determine. Nonetheless, the idea has been researched for several decades. Sociologist Lev Gudkov is one of those who most clarified the given subject. In his works, which have become classics, he characterizes the Homo Sovieticus type these ways:

- Conformity, the desire to be “like everyone else.”

- Adaptation to the existing social order, and a readiness to require less.

- Simplicity and Limitations in the planes of ethics and intellect. The “Soviet Person” considers this primitivism an advantage.

- Hierarchy. These people have a faint idea of “the elites.” They are certain: as with material goods, so too human rights, respect, intellectual quality and so on, are divided depending on “position” and "status.”

- Chronic Dissatisfaction in life’s arrangements. Because of this, the Soviet Man believes that he has the same right as the officials and authorities to cheat. He acts loyal but really takes care only of his own interests.

- Uncertainty in himself. He does not feel secure socially or capable of living in “stability” because of the undeveloped state institutions. This gives rise to a chronic complex of undervaluation.

- The Soviet Man’s own disenchantment and undervaluation are compensated by feelings of uniqueness and superiority. From here the ideas of “empire” and “the great nation” emerge. With these are also linked xenophobia and sometimes even paranoid certainty that one is surrounded by enemies and hostile conspiracies.

- Corruption. As a result, there is a readiness to tolerate rough treatment of oneself from the authorities. This corruption has different sides – not only do the authorities, in the form of different individual officials take bribes, but the population itself “sells out” for privileges, promises, or symbolic tokens of abundance.

Politically Uncultured

People who miss the Soviet Union or who consider themselves citizens of the USSR are characterized by several signs of “Soviet Man.” However, it is unfortunate that traces of Homo Sovieticus can be found in a wide swath of Ukrainians.

Apart from that, those nostalgic for the USSR overwhelmingly evince low social activism and are not ready to partake in actions to support their viewpoints.

“They can grieve, but that means little,” explained Yaroslav Hrytsak.

Which is a greater threat to the future of the country: a villager who lives on the minimum pension of 1373 Hryvnia a month and regrets at times that there used to be more to eat; or the corrupt values of the “Soviet Man” in the younger generation?

If the country is not to be overwhelmed by “Homo Sovietici” then it is necessary to change the political culture.

Researchers have delineated four such cultural types:

- First: actively antidemocratic, characterized by the epoch of Stalinism.

- Second: passively antidemocratic, inherent to the period of stagnation, when the system was still totalitarian, but the “silent majority” no longer cared about protecting it.

- The third type is actively democratic, characterized by developed states in which people are ready to fight for democracy.

- The last type is passively democratic, in which democratic principles are declared, but there is not a critical mass of people to embody them.

This fourth type essentially dominates in every region of Ukraine. Actively antidemocratic types outnumber actively democratic.

The same is true of simply “wanting to join the EU.” Changes in the minds of millions will not occur quickly. One must start with changes inside oneself – Europe begins there in Ukraine.

Read more:

- 'Homo putinus' - the successor to 'homo sovieticus

- Many Ukrainians remain “Soviet people” decades after collapse of the USSR. How to eliminate “Bolshevism of the mind”?

- The decolonization of Ukraine is irreversible - Viatrovych

- Post-Soviet states built the Soviet-style caricature of capitalism

- A new man emerges in Russia – Homo Putinisticus – Eidman says

- SBU Archive director: “Cause of death - Ukrainian” in 1933 registry

- Building a new Russia means rooting out Stalin's destructive Soviet legacy

- Disentangling the 'fraternal' Russian and Ukrainian peoples in 1991 and now

- "Immortal regiment" march in Toronto - shameful display of Russian propaganda

- Stages of Russian occupation in a nutshell

- Why Americans are "stupid," according to Russians

- Russia’s accelerating return to Soviet past: Key dates under Vladimir Putin