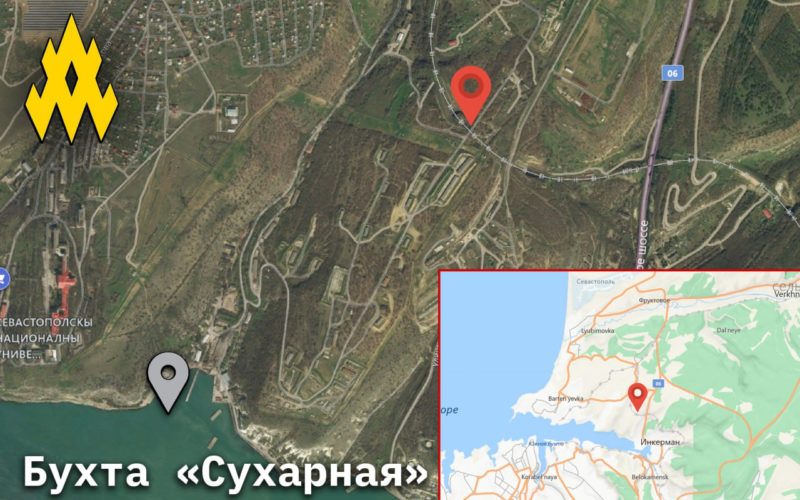

On 22 September, a Storm Shadow missile strike struck the building of the Russian Black Sea Headquarters in occupied Sevastopol. It was timed to a high-ranking meeting, which gathered the top brass of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. 34 Russian officers were reported killed, including the Black Sea Fleet commander.

Making it possible was Ukraine's resistance movement in occupied Crimea, which defies risks of imprisonment and torture to work towards their goal: an independent Ukraine free from Russian occupation.

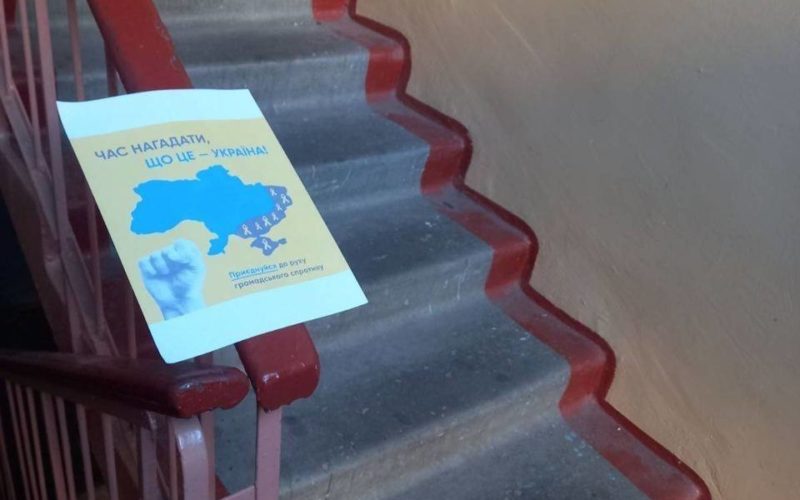

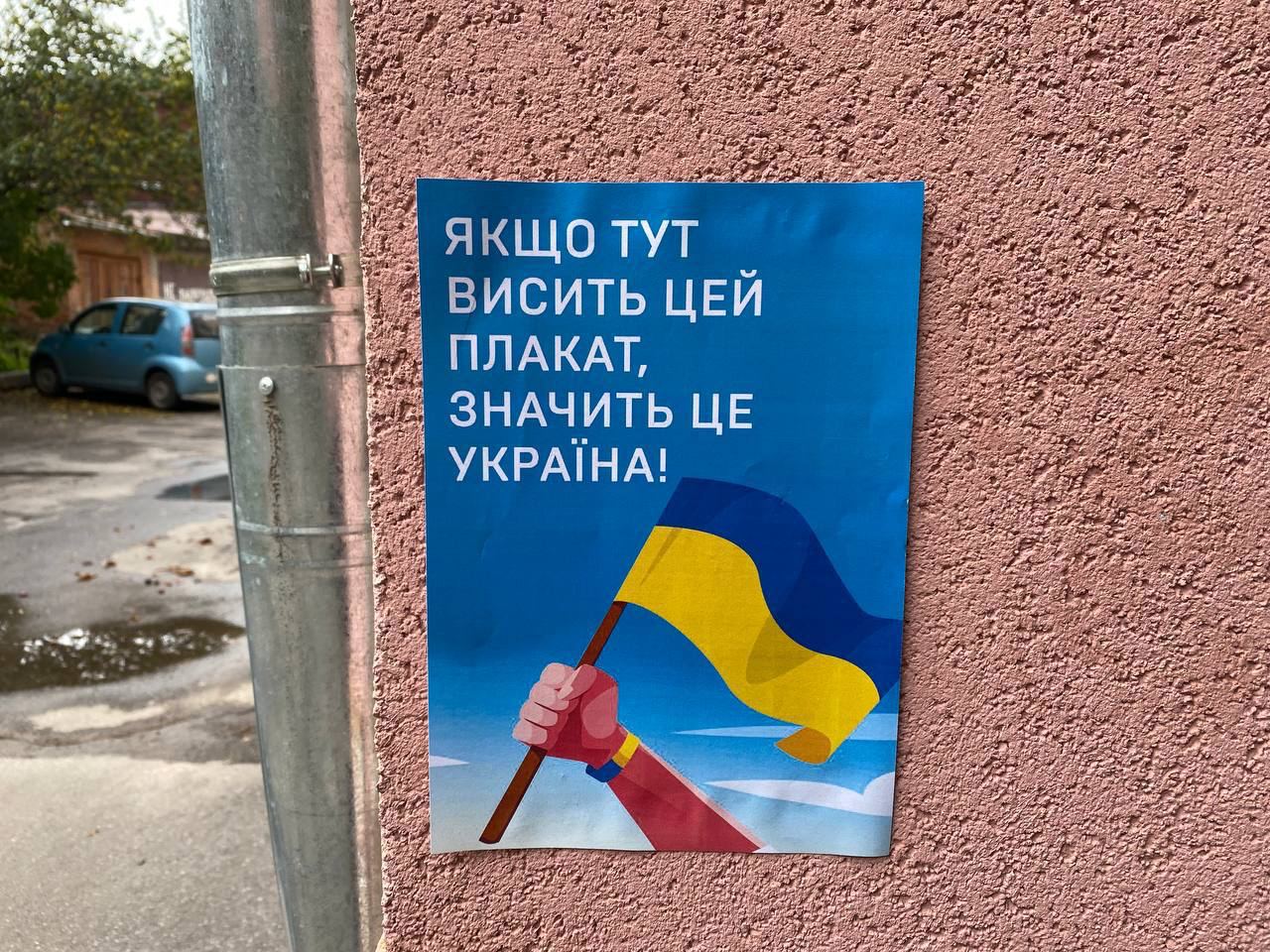

But the resistance extends beyond such active measures: peaceful actions like hanging leaflets stating that the Ukrainian army is close and urging Ukrainians to reject Russian passports are a step towards liberation, representatives of the underground tell Euromaidan Press.

Atesh: Ukraine's resistance fighters bomb railroads and collaborators

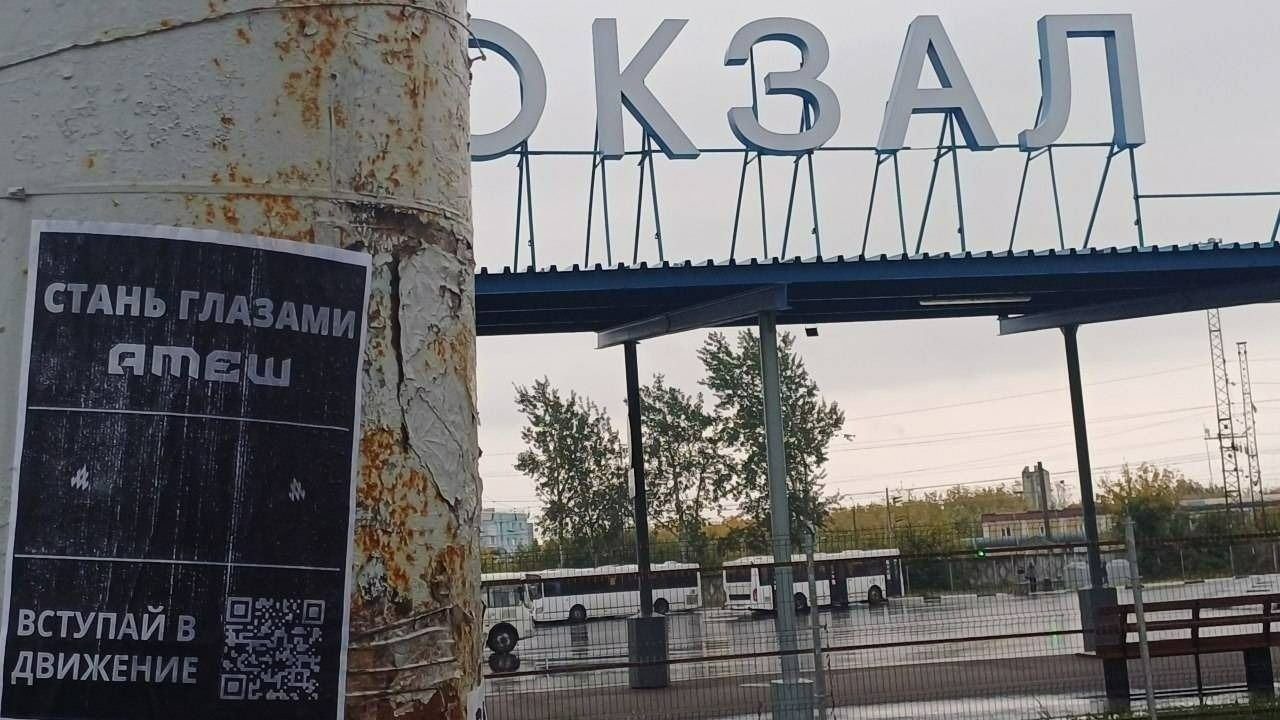

One of the most well-known ones is Atesh (“fire” in Crimean Tatar), which describes itself as a military movement of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars with the aim of liberating Crimea and all other Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia.

It arose in Crimea in the summer of 2022 and now includes 1,800 agents, part of whom are directly in the Russian army, “from Kaliningrad to Siberia.” In fact, it arose with the purpose of capitalizing on the resentment of those forcibly mobilized into the Russian army. Most of Atesh's members are Ukrainians from occupied territories whom Russia conscripted in violation of the Geneva Conventions:

“This is how they try to help their homeland. But [we also have] some Russians who do not support such brutal actions against their neighboring country. They do not fall to propaganda and want this horror under the name of ‘special military operation’ to end sooner. Some Russians want money,” an Atesh coordinator who asked to remain unnamed explained in a written message to Euromaidan Press.

Atesh does not make any bets on Russian protests: the Russians are not ready to resist, as “authorities are sacred to them,” and Russian repressions are effective in keeping Putin in power.

But they are ready to rat. The movement boasts of having lots of information from within the Russian ranks. On Telegram, Atesh regularly reports on the locations of Russian military bases, logistics of Russian missiles, and positions of Russian air defense units in occupied Crimea, and even the production of Russian missiles in Moscow.

It also claims that it helped guide a missile strike on occupied Sevastopol on 13 September, when Ukraine destroyed Russia’s Rostov-on-Don submarine and Minsk landing ship.

Other notable operations include destroying a railroad section on 11 March, disabling Russian military transport, and regular attacks on collaborators. One of them killed the quisling governor of Kherson Oblast Kirill Stremousov.

We'll help you save your life and earn good money. In return, we ask for information and assistance in ending the war by expelling Russian troops from Ukraine!

Our agents are already among you, we are on the streets of the city, and we see you every day. And we are already in action,” it says in social media posts.

One of the ways Atesh promises to “save the lives” of Russian soldiers is by teaching them to wreck their own military equipment. An online school teaches Russian soldiers with second thoughts about invading Ukraine such crucial skills as “burning the wiring of a tank, disabling a BMP engine or making the engine of an MT-LB overheat.”

“Nobody will prove your involvement!” Atesh assures, promising that the saboteurs will get their soldier’s wages while staying out of combat as their equipment is repaired. As well, it promises to pay Russian informers.

The FSB constantly tries to penetrate Atesh’s ranks, a coordinator told Euromaidan Press. However, Atesh is good at finding them and knows how to filter out potential agents. Furthermore, most Atesh agents operate autonomously to prevent information leaks.

“What the Russians are doing in the occupied territories is pure horror. Like barbarians, they are trying to burn out everything Ukrainian or Tatar from our native lands. There are repressions, deportations, zombification of children. This is the worst thing. And it must be stopped as soon as possible,” Atesh explains its motivation.

There are other partisan movements, but Atesh is one of the largest; its success is that it manages to encourage not only Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars but also some Russians to take action: “few can do this,” Atesh says.

“We accept any help: intelligence data, valuable contacts in the occupied territories, dissemination of information about our activities, as this helps us grow even more and work more efficiently,” Atesh stresses.

Yellow Ribbon: proliferating non-violence

The Yellow Ribbon movement is the other pole of resistance in Ukraine: that of non-violence.

For Kateryna, a Yellow Ribbon member who asked for her last name to be withheld, the story of active resistance started on 27 April 2022, on a large protest against the Russian occupation of Kherson. Thousands of Kherson residents waved flags and shouted “go home” to the Russian troops on their streets. There, she met the coordinators of the nascent Yellow Ribbon movement and other like-minded Ukrainians who were ready to covertly resist Russian occupation.

Soon, open dissent was a thing of the past: Russian troops started opening fire at peaceful rallies, wounding and killing the locals. Resistance shifted to the underground.

Ivan, now one of the Yellow Ribbon coordinators, grabbed his mom’s bundle of ribbons, cut them up, and took photos of himself hanging them everywhere: he wanted to show that any material at hand could be a statement against the occupation authorities. A Ukrainian blue and yellow flag is too risky to hang under the eyes of the occupiers, “but things like a yellow ribbon could be hung discreetly, and it became a symbol of resistance,” the activist says.

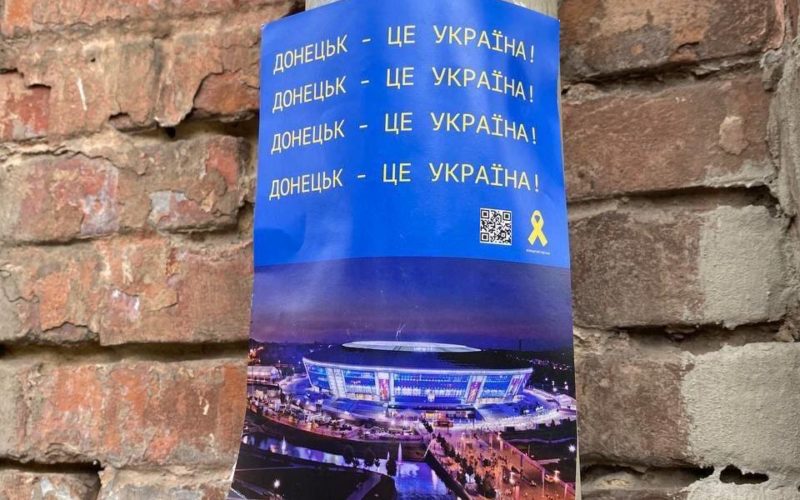

Over the next months, Kateryna scrawled pro-Ukrainian graffiti, tore down and burned Russian propaganda posters, and spread calls to join the ranks of Yellow Ribbon. Over the one and a half years, the acts of non-violent anti-occupation resistance snowballed: now, there are at least 10,000 members in the Yellow Ribbon chat, are all from all parts of occupied Ukraine – from Donbas and Crimea, occupied in 2014, to Kherson Oblast, annexed by Russia in 2022.

The Yellow Ribbon’s Telegram channel, with over 20k subscribers, unites Ukrainians under Russian occupation, showing them they’re not alone, and sends a message to the Russian occupiers. The pro-Russian Telegram channels often fume over “unknown partisans” spray-painting graffiti like “Nova Kakhovka is Ukraine” in the occupied cities.

“Their reaction means we’re doing it right. Maybe we don’t do enough; after all, people at the front lay down their lives. But even these little actions will signal that it’s all worth it, that it’s worth liberating our territories, and I believe that it will soon happen,” Kateryna says.

The Russians try to infiltrate Yellow Ribbon, too. The first red flag is if newcomers start asking to be given the coordinates of existing activists because they’re not brave enough to do the task by themselves. “They ask lots of questions but ultimately don’t perform any resistance tasks, don’t hang up ribbons or anything,” says Kateryna. For safety reasons, no contacts of activists are ever revealed: like Atesh, they operate independently.

Some 70% of the Ukrainians under occupation in Kherson Oblast have a pro-Ukrainian position; 30% could be tentatively called pro-Russian. Kateryna doesn’t feel safe saying she’s part of Yellow Ribbon anywhere: she never knows where a snitch can be.

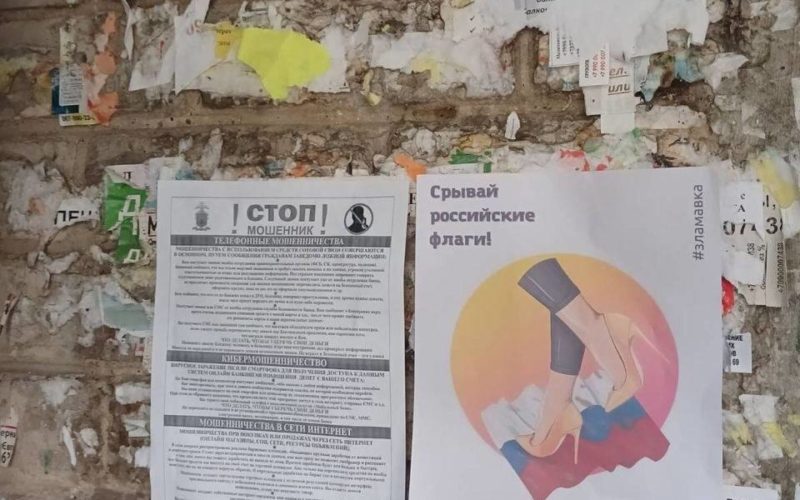

Newcomers are offered a list of activities: create pro-Ukrainian graffiti, hang leaflets or verses by Ukrainian poets, tear down Russian announcements, burn Russian newspapers and leaflets. “Just taking a book of Taras Shevchenko and take a photo of it on the backdrop of the city is already an act of resistance, it shows how you are fighting against the occupation powers,” Kateryna says.

One of Yellow Ribbons's campaigns was to turn the ubiquitous Z, a symbol of Russia's occupation campaign, into an hourglass in the colors of the Ukrainian flag, signaling the ticking clock of inevitable deoccupation. Another one involved spreaing graffiti of the letter "ї," unique to the Ukrainian language. Photo: Yellow Ribbon

Yellow Ribbon is exclusively non-violent, but Kateryna is “positive” about Atesh: “The more dead Russians there are, the happier I am.”

Is violent or non-violent resistance in Ukraine more effective? Both, says Kateryna, and there is a gender dimension to it.

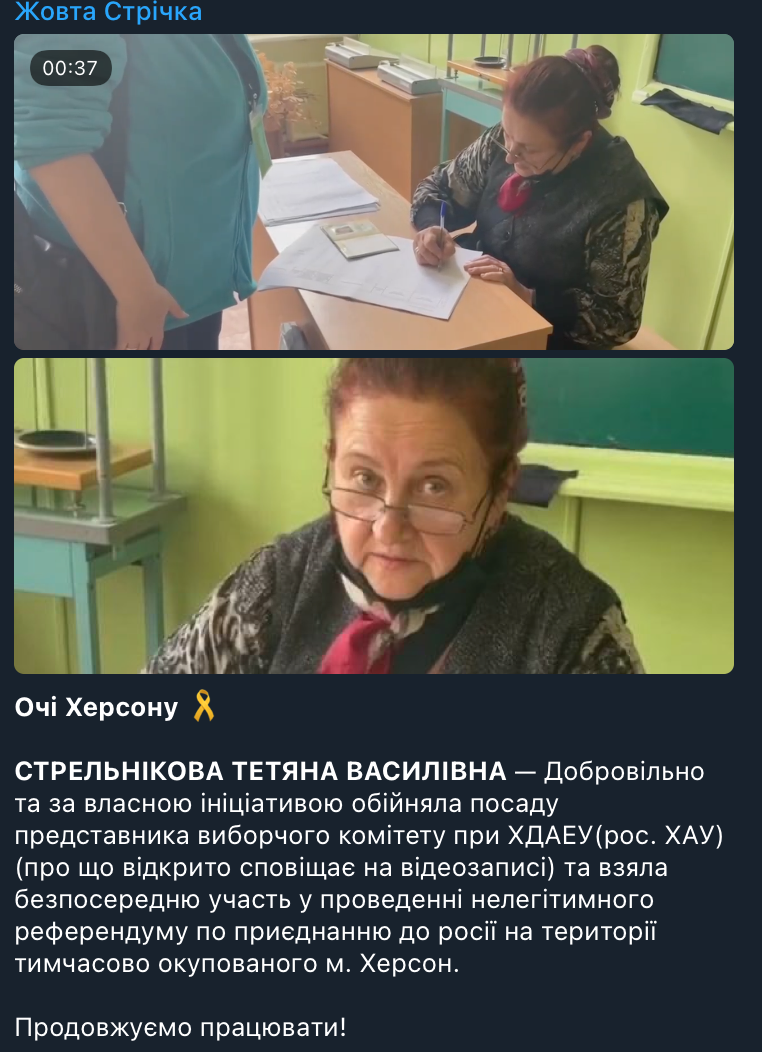

“There are more men in Atesh. But women living under occupation also want to be part of Ukraine’s future victory. Not every person has the strength to take up arms and go to the front line to defend their country. But being a woman, you can make your contribution, starting from gathering intelligence on collaborators who create occupation voting stations, so that they won’t be able to claim they are great ‘patriots’ after liberation,” Kateryna explains. Yellow Ribbon sends proof of collaborators to the Ukrainian agencies.

The act of resistance itself is crucial. “If people don’t see that resistance exists, they think there is none and that Ukrainians have come to terms with being under occupation. This is not true, and even the smallest acts of resistance serve as proof,” Kateryna explains.

Recently, Yellow Ribbon launched a flashmob to increase the visibility of resistance in Ukraine, answering an allegation by techno magnate Elon Musk that there is none.

Elon Musk recently alleged there is no resistance movement in occupied Ukraine. In response, @yellowribboneng launched the #ElonWeAreHere flashmob, the goal of which is to show how many Ukrainians are waiting for liberation under Russian occupation, from Crimea to Donbas pic.twitter.com/mYZixNAOaL

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) November 4, 2023

Being an activist is easier in Crimea, occupied by Russia in 2014: there are no checkpoints or non-stop surveillance like in Ukrainian territories occupied after 2022. So, the largest number of Yellow Ribbon activists are in occupied Crimea, many of whom are Crimean Tatars, the indigenous population of Crimea who “are not content with Russia and have lots of reasons to resent and oppose it.”

Kateryna’s favorite action was from occupied Crimea: a Ukrainian flag was flown into the sky on balloons.

“When I saw it, I couldn’t hold back tears,” Kateryna recalls.

“The situation in Crimea is stable; they can do lots of graffiti and leaflets, fly balloons with flags, and nobody cares too much. For me in Kherson Oblast, it’s much more difficult; to paint one graffiti on some outskirts, I must plan everything ideally,” Kateryna explains the daily realities of the underground.

Activists can be stopped at any turn and searched. To avoid getting caught, they must constantly delete photographs and contacts from their smartphones. Kateryna is not subscribed to the pro-Ukrainian Telegram channels to avoid giving herself away; she finds them by heart.

To hang up yellow ribbons, one cannot, for example, take the whole roll of yellow string but take a bunch of mismatched fabric strips, saying, “I’m going to tie up my tomatoes in the garden with them,” and then hang only the yellow ones.

The leaflets: you can take only a couple and hang them only in the early morning or at night. The surveillance patrols follow identical routes: activists can plan their paths to avoid them.

The Russians were “absolutely pissed off and vicious to the local pro-Ukrainian population” right after occupation. Each time Kateryna steps out for groceries, she doesn’t know if she will make it back, as the Russians hurl “inappropriate phrases” in rounds of “moral humiliation.” Now, they have scaled up searches of activists once again, and Yellow Ribbon needed to scale back their activities to avoid being identified.

Why does Kateryna resist? “I want my future kids to live in a free democratic country, for them to have a choice where to live, learn, to be able to travel freely to any country. I want my kids to journey to see Europe, America, Asia for themselves, to be able to freely choose their way of life, way of thought, way of anything. Russia will not give any of this.”

One and a half years of Russian propaganda is impacting those under Russian occupation who do not have access to non-Russian information. Mostly, these are seniors. Children in schools are being slowly brainwashed: they recite the Russian anthem and get stationary with the Russian flag and Putin’s portrait. However, there are not enough Russian textbooks, only a few per class: the Russians do not want to expend resources on a territory that they fear will soon be liberated, Kateryna believes.

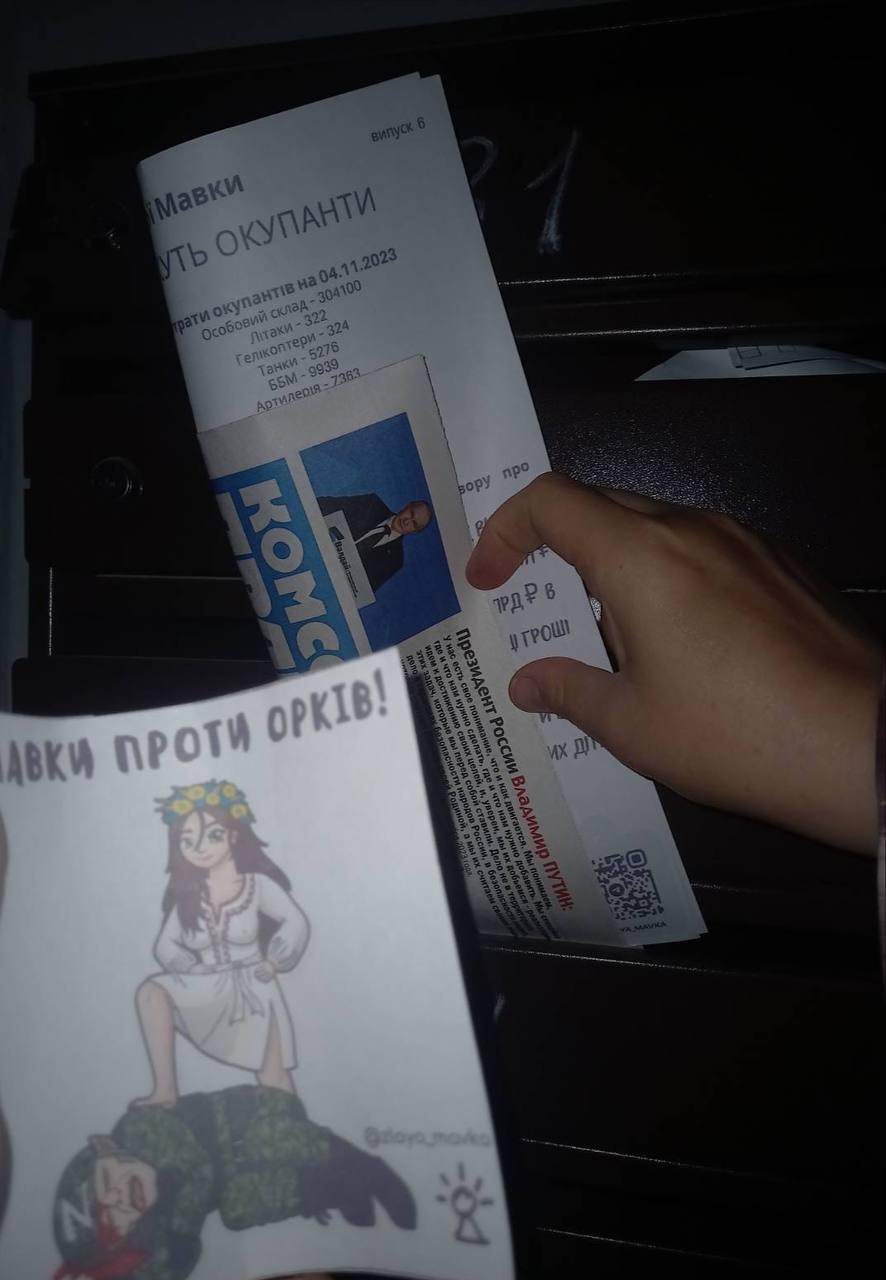

Angry Mavka: women’s underground with dash of spiked moonshine

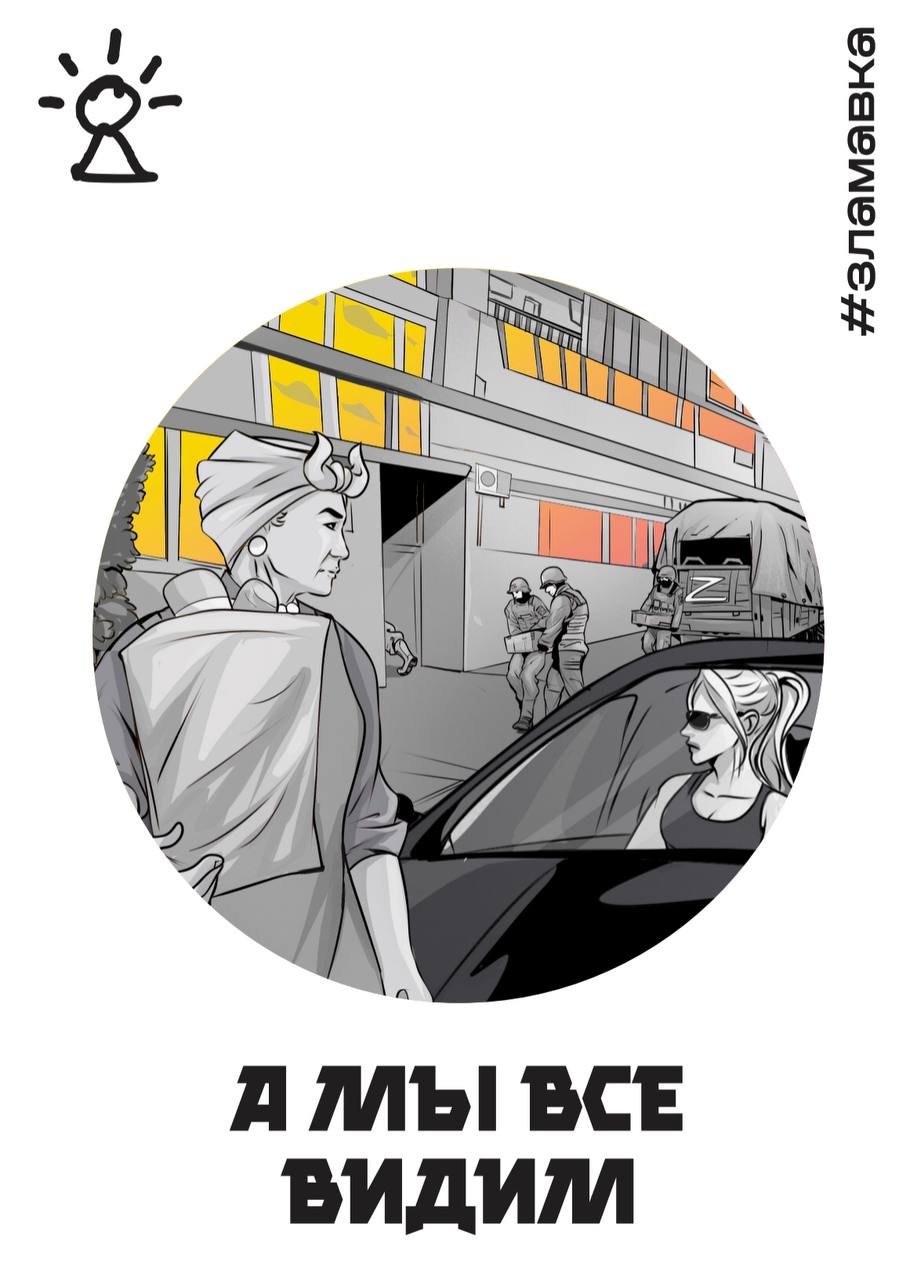

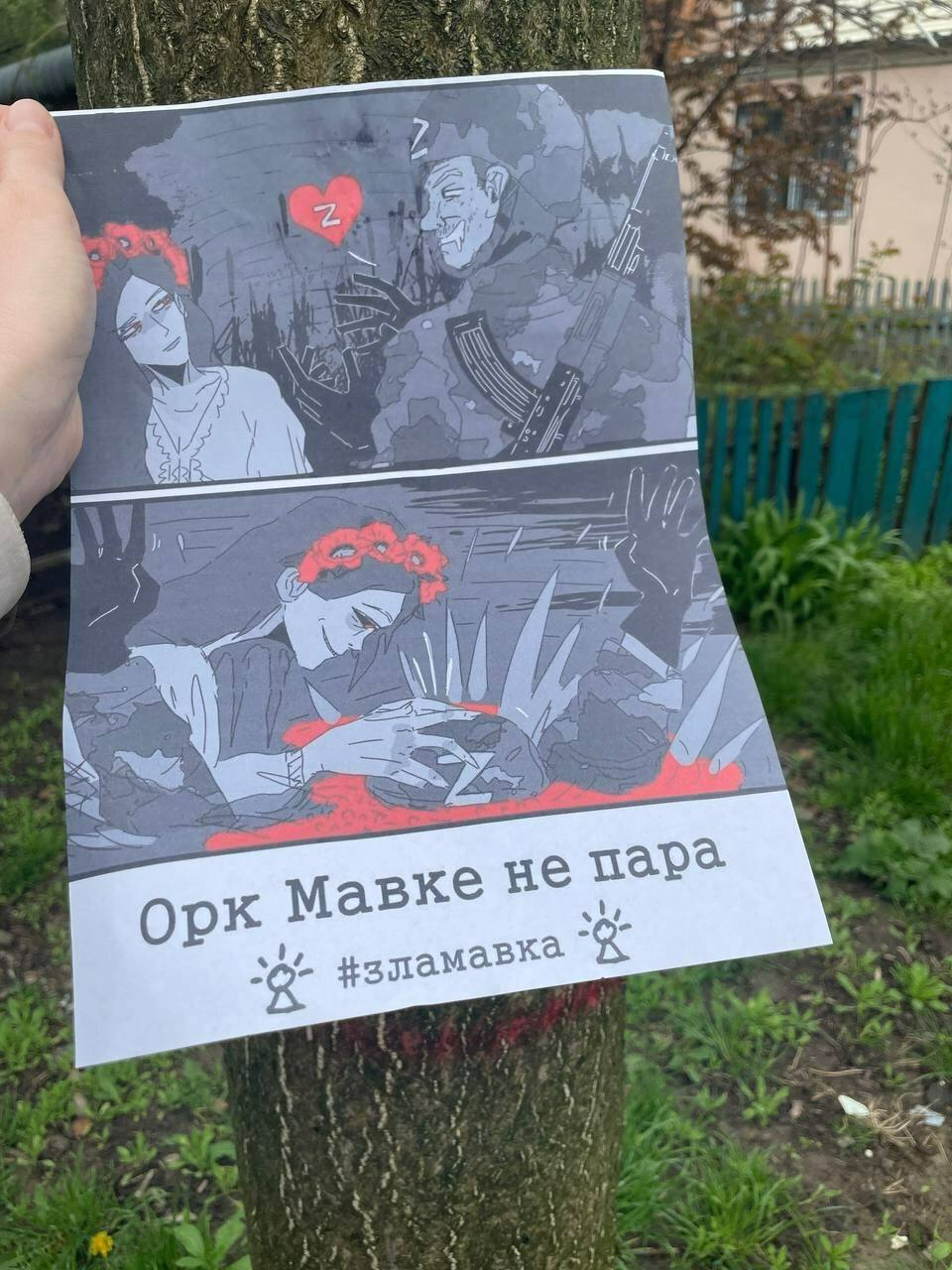

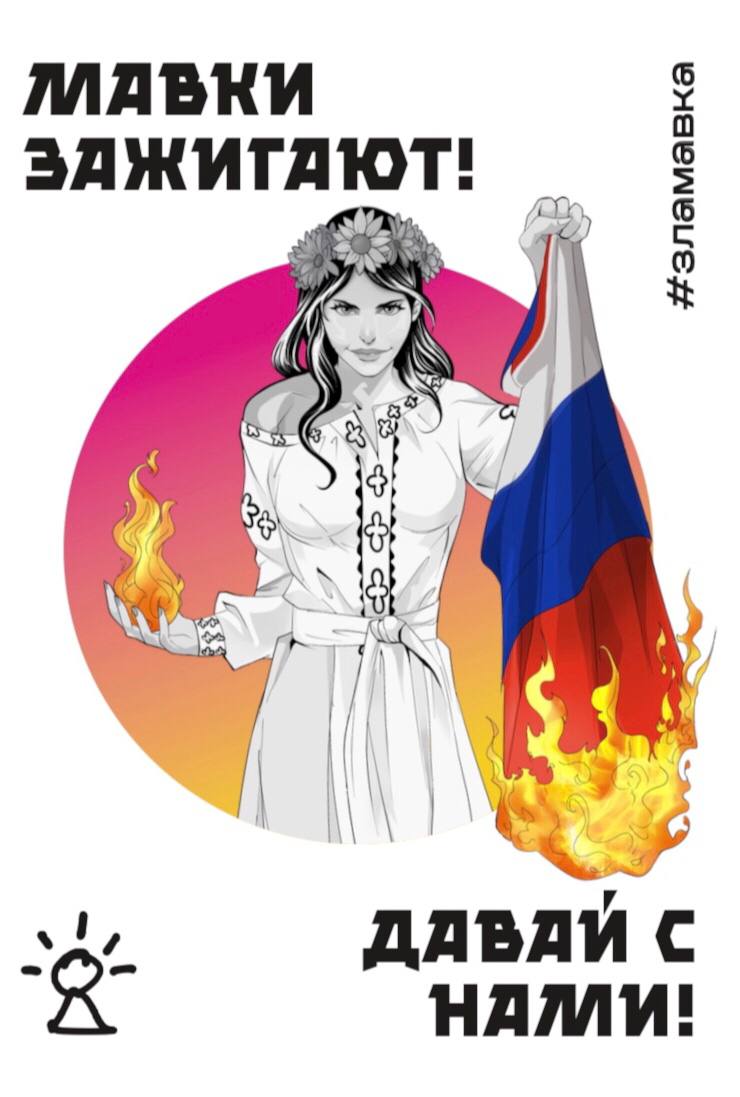

Getting its strength from the Ukrainian mythological Mavkas, malevolent restless spirits of young women who could tickle young men to death, “Angry Mavka” arose as specifically a women’s resistance movement in February 2023 in Melitopol, one of the centers of Ukraine's resistance.

“My girlfriends and I understood that in general, life under occupation is no walk in the park, but for a woman, it is even more difficult,” Mavka, who declined to give her real name, told Euromaidan Press.

“As well, the Russians did not expect that a group of women could mess with them; they were looking for young guys.” And so arose the Mavka; pitted against the orc, the two mythological creatures were a suitable manifestation of the situation in occupied Ukraine.

Mavka’s friend created the posters; the movement got a face and a Telegram channel. They did not expect so many girls to join: first from Berdiansk, then the entire occupied south Ukraine.

“The Russians harass women on the street; they are very rude and behave like they own this place. Going down the street, they can grab a woman by the arm. And the Kadyrovites, who like driving around in cars, can suddenly screech to a halt next to you, and they start yelling, ‘hey beauty, come here.’ In a normal city, you know you could get help, but these are armed men, and if anybody stands up to help you, they’ll fall victim very fast.”

Mavka’s friends have not been sexually assaulted by the Russians, but “it’s clear that it happens”: one friend’s flat was broken into and ransacked. If she were home, who knows what would have occurred.

Hence, one of the movement’s purposes is self-defense: “at least some of the Russians would be afraid to harass girls because they might not know where that could lead.”

One time, this led to “Mavka’s kitchen”: the girls got a chance to deliver some pastries to the Russian soldiers’ quarters. And then, when the Russians enacted a Dry Law prohibiting anything stronger than beer, the Mavkas delivered a batch of moonshine with “very generous additives” of laxatives. “When the opportunity arises, we always take advantage of it; soon, New Year’s will come…”

First of all, Mavkas stick up pro-Ukrainian leaflets: “we really want them to get these messages, so they understand they are not welcome, don't feel at home here.” But even this “simplest form of non-violent resistance’ is now complicated: CCTV cameras are now on every corner.

Trending Now

So, the women came up with a solution: 50 ruble notes with a changed design. The activists simply drop these “like the real thing” bills on the street, where they immediately get picked up – “everyone picks up money”; but instead of the Neva statue of St. Petersburg, a Mavka sits on a throne, saying, “you’re not in Russia, you’re in Ukraine.”

Over a hundred women are Mavka activists; but many more put up leaflets, share information, etc.

“It’s difficult when you can’t talk with your friends or neighbors, as you don’t know who will give you over to the occupation authorities tomorrow. When Mavka appeared, girls started writing me, like pen pals; they could simply tell me their story, ask for advice. We can organize, share insider information with each other. So, it’s not just a resistance movement, but a women’s club, and that’s important, too, when you can’t share your thoughts with anybody.”

In general, the atmosphere in Russian-occupied Ukraine is one of fear, resembling the societal paranoia of the GDR: “you can’t chat on the street or at the market, because there are ears everywhere. Everyone's afraid that someone will snitch. Not only that your own people will, but also that ‘orcs’ walk around, they dress up in civilian clothes and walk around pretending to be civilians.”

What kind of women join Angry Mavka? One category is generally pro-Ukrainian. “They clearly know that they’re in Ukraine, that the Ukrainian Army will soon liberate us, that we need to do something too, that we can’t let the occupiers get away with anything, that we need to torment these orcs.”

A personal vendetta drives the others. They have “already experienced the best of the Russian world firsthand” and are searching for ways to take revenge. One woman’s husband was arrested in 2022 because he fought against Russian proxies in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Till this day, she doesn’t know where he is and if he’s still alive.

Meanwhile, the space for dissent is shutting down in the occupied territories. Ukrainians were forced to get Russian passports. Otherwise, they are denied medical and humanitarian aid, as well as prescription medicines and insulin. Failing to get a Russian passport will mean deportation next year.

“There's simply no way to survive without this passport. It's not a question of agreeing to live under Russia; it's a question of survival,” Mavka says.

Anytime on the street, Russian soldiers can search your pockets and phones. In the evening, a car can pull up to your building, and Russian soldiers will go from apartment to apartment, searching for symbols and documents that can give away partisans and the “liberation-hopefuls.”

“They always find a USA flag, it’s so ridiculous,” Mavka scoffs at the Russians’ preoccupation with their American archnemesis. “Where’s the Bandera portrait, or a [Ukrainian] trident; gentlemen, you’re slacking!”

Russian propaganda takes its toll. Organizations to indoctrinate kids are “sprouting like mushrooms; every day there’s a new one where children are simply being brainwashed, they're given weapons, they hold these demonstrative marches. It's just horrifying,” Mavka laments.

And amid all this, “sometimes you lose heart because it's all been so long. Sometimes you're so immersed in all this propaganda that you catch yourself starting to believe in something, for example. You understand it's a lie, but there's so much of it already that you start believing it; these thoughts creep into your head: what if?.. what if?... and so on.”

The elderly are especially vulnerable, as they don’t know how to access Ukrainian media sources on the internet. This is why Angry Mavkas have created their own newsletter with blurbs of information that the occupiers keep silent about. Each Monday, they are scattered in mailboxes, under doormats, on the street, so that these kinds of people can see it’s not all like they’re being told. “This is probably one of the most important actions of those we're doing because it really does help our people not to drown in this propaganda.”

After over a year of occupation, many Ukrainians are “just holding on” under the press of propaganda. Others are so steadfast that they “don’t let this Russian world into their heads even for a millimeter.”

There are, of course, the collaborators. One category of them are “Russian world lovers; poorly educated people with a limited worldview who haven’t seen anything besides Russian, Soviet films in their lifetime.”

The second are “opportunistic losers.” These could never get a proper job, but suddenly got a second lease on life: “all they needed to do was to shout how much they loved Russia louder than others,” Mavka says.

The underground started from scratch after occupation

Volodymyr Zhemchuhov, Hero of Ukraine, a Ukrainian partisan from Luhansk Oblast who was a prisoner of the Kremlin, has a less than rosy view of the Ukrainian resistance. He divides the resistance of Ukraine into two categories: partisans like Atesh are those who take up arms and become combatants, and the underground like the Yellow Ribbon, which is engaged in civil resistance.

Early prognoses made by the US-based Institute for Study of War of Ukraine’s partisan movement becoming a decisive force for victory were proven wrong: “They probably thought that the war would be like in Afghanistan or Chechnya, where partisans hid in the woods, in the mountains.”

But in occupied south Ukraine, there are no large forests that could offer shelter.

Moreover, the only partisan cell prepared by Ukraine prior to Russian occupation, out of the territorial defense of the Kherson Oblast, was fully demolished, sold out to the FSB by traitors in their ranks and Ukraine’s Security Service. One partisan cell of 12 people in Kherson Oblast lasted until May 2022 but was also betrayed. Others were captured; some put up a fight and died. Only 3-4% remains from the underground prepared by Ukraine prior to the full-scale invasion, Zhemchuhov believes.

“Most of the partisan movement is now starting from scratch. They are local people with a lot of patriotism,” Zhemchuhov says. But there was not a lot to begin with: only in January 2022, one month before Russia’s full-blown war, did Ukraine adopt legislation legalizing partisan activities, such as taking up firearms to fight occupiers.

Fostering this new partisan movement is a game of cat and mouse. In the summer of 2022, Ukraine brought partisans-to-be into government-controlled areas for two weeks of training in conspiracy, safe messaging, and explosives. Three priority directions were given:

- to kill collaborators,

- destroy logistics such as bridges and railways,

- and identify coordinates of the concentration of Russian military equipment, barracks, and headquarters.

The first and third are the most painful for the Russians.

That summer, the partisans were very successful: each week, traitors were killed.

“But Russia caught on and applied proven practices of fighting Chechen partisans. They sent a lot of Rosgvardia and FSB detachments to the occupied territory, used the same tactics as in Chechnya. At 5 AM, many troops arrived in a settlement or city district; some surrounded the area, and others went on raids. They checked people, passports, correspondence, smartphones, computers, searched for weapons. And this is how we lost about 50% of the underground by the end of last year,” Zhemchuhov laments.

He bemoans the young partisans who did not follow the conspiracy guidelines: “They did not follow the instructions they were taught. It’s laziness: they did not clean their smartphones, did not delete photos, coordinates, correspondence in messengers, they did not clear the cache, trash with deleted messengers, photos, videos on laptops, and because of this they were captured.”

Changes were made, conspiracy was boosted, and in the spring of 2023, the partisans resumed their pace of one killed collaborator, military or railway explosion per week. Russian President Putin even started saying in televised speeches that the death penalty should start to be applied to partisans. He forbade exchanging the imprisoned partisans, and they were tortured and sent off to Siberia to camps.

“Because of the torture, we also lost many cells; people broke and betrayed their comrades. Unfortunately, we lost a lot of the underground this year,” Zhemchuhov explains.

Many Ukrainian partisans were given the Hero of Ukraine awards posthumously: three partisans fought back and blew themselves up together with Rosgvardia soldiers when their house was surrounded.

The remaining partisans all cooperate with the SBU, military intelligence, or territorial defense: to survive, support with weapons, special equipment, and communications is needed.

The most effective operations? Zhemchuhov names a strike on the Black Sea fleet headquarters in Sevastopol on 22 September, when partisans found out when Russia’s top brass would gather in the building, and a missile hit it at precisely that time.

As well, the timing of the explosion at the Crimean bridge on 8 October 2022 was no coincidence: it took place precisely when a train with fuel was made to stop on the bridge, exacerbating Ukraine’s missile strike.

Huge ammunition warehouses and airfields in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts, near Khrustalnyi, were blown up thanks to coordinates provided by partisans.

But now, a huge number of the resistance movement is jailed: over 1,000 partisans only in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, and 4,000 underground members who stuck up leaflets and conducted other acts of resistance.

Replenishing the ranks is turning out to be a problem: the Russians’ “terror and repression are doing their job.” The occupation administrations will pay Rub 500,000 ($5,500) to anybody who gives information on the whereabouts of partisans or their caches with weapons.

As lots of the youth supports the resistance movement, the occupiers search children’s smartphones in schools. Earlier, a policeman would come for this task each week in occupied Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts. Now, the occupiers are assigning an “informer” to every school and university, the purpose of whom will be to create an agent network to monitor the children, collect information, and snitch on each other just like in Soviet times.

“Writing anonymous letters about each other is very much encouraged, financed by the authorities, many authorities support these snitches, promote them at work. There are many cases when people write anonymous letters about each other just to get promoted at work and not to lose their jobs. This is very much supported by the FSB,” Volodymyr Zhemchuhov tells about practices born of the oppressive state apparatus of the Soviet era.

The “terror and repression” against the partisans manifests itself especially in the areas of active fighting in eastern Ukraine. In villages next to locations of Ukrainian artillery and missile strikes on concentrations of Russian troops, the Russians employ “World War II” measures: 10-15 men from the settlement who were said to be pro-Ukrainian are taken to the basement and tortured for a week up to being killed, just to find as much information as possible about who supports Ukraine among the locals.

This tactic is also used when the Russians come to a new territory: they torture people to collect a database about the underground for themselves. One year ago, they needn’t do even this: Facebook, with its track record of liked posts, was the occupiers’ database.

However, male partisans are now a rarity in occupied eastern Ukraine. As the Russians ramped up the coerced mobilization of men in occupied territories to throw into their war, most of the men of conscription age had fled. Only women, underage youth, and elderly men remain, bringing the rate of partisan combat operations to one in half a year – “such is the statistic of the people left.” Intelligence is still collected, though, helping guide Ukrainian strikes.

The newly-occupied areas of south Ukraine have more prepared cells remaining who carry out armed resistance partisan actions. Also, the spirit of the underground has revived in Crimea, which saw active partisan combat actions. Railways were blown up several times, and trains with equipment and wheat stolen from Kherson Oblast went off the tracks. The communications of the Russians were undermined, and an assassination attempt was made on Oleg Tsarev, a pro-Russian exiled Ukrainian politician sentenced to 12 years in prison in Ukraine – an attack Ukraine’s Security Service took responsibility for.

Ethnic Ukrainians who had been living in Russia and are Russian citizens also join the resistance: they become part of combat units or help the partisan movement covertly.

But keeping the partisan movement alive is a challenge. Pro-Russian associations have sprung up against Ukrainians awaiting liberation from Russian occupation. Titled “Smersh,” named after the Soviet World War II “Smert Shpionam” (“Death to spies”) counterintelligence operation.

Working, as per Zhemchuhov, in close cooperation with the FSB, the Crimean, Sevastopol, and other “Smersh” Telegram channels establish the identities of anybody not thrilled with Russia’s war. Videos where they are seized and forced to apologize or are imprisoned follow.

Many videos show FSB officers arresting members of the Ukrainian underground: a recent one shows the arrest of the alleged organizer of the Tsarev murder attempt. Another one claims to show the detention of a woman who filmed the results of the missile strike on the Russian Black Sea headquarters.

However, the Ukrainian government is doing its part. It has passed a law that legalized the partisans and is now funding them. “If a person signs a civil contract with us, we provide full guarantee of social and legal support for that person and their family. If he is captured, he can be sure that the country will not abandon him, leave him and his families will receive him, Ukraine will fight for them, they will receive financial assistance and social support,” Zhemchuhov assures.

Moreover, Ukraine is supporting the Russian partisans as well: 300 Russian citizens who helped Ukraine are on Ukraine’s POW exchange list.

Violent and non-violent: Both types of resistance in Ukraine matter

While radically different in approach, the partisans and underground deliver “psychological pressure” in tandem, a spokesman for Ukraine’s Special Operations Center with the callsign “Ostap” told Ukrainska Pravda. Russian soldiers walking in occupied cities will see pro-Ukrainian leaflets that are not followed up with missile strikes as empty threats. And if there are only car bombings and special operations without civil resistance, the Russian soldiers will believe that only the Ukrainian Army is fighting against them, while the locals support them.

But “when a Russian soldier walks around Melitopol and sees a trident painted somewhere, and then reads on Telegram that a car has been blown up somewhere, a picture comes together for him. He understands that both combat groups and civilians are working against him,” “Ostap” said.

What Ukraine's resistance fighters want to tell people pushing Ukraine to freeze the frontline and negotiate with Russia

Atesh: “Foreigners must understand that this is not some kind of territorial conflict for us; it is existential. Putin and other Ruscists want to destroy the Ukrainian nation. And if they are not stopped, they will keep trying. You must help us so that other countries neighboring the Russian Federation do not share the fate of Ukraine.”

Kateryna (Yellow Ribbon): "Ukraine froze the front line in 2014-2022, and what was the result? After eight years, the Russians gathered forces and means and went on the offensive. Who will guarantee this won't happen again? For how long will the problem be postponed? For five years or ten? This means my children will have to go to war. It’s better to deal with this now, so that the next generations can live in peace. We failed to resolve the problem of Russian aggression peacefully; this means we need to finish the job by force.

Ukraine is not the endpoint for Russia; their imperial plans are much bigger and broader than Ukraine. Russian propagandists claim that Poland and Lithuania are originally Russian lands. It is unlikely that the war will end in Ukraine; if it is postponed, there may be even worse consequences: the Russians will come up with some new, scarier weapon that can cause much more harm to people."

Read more:

- Ukrainians of occupied towns protest against Russian occupation

- Russia squashes dissent, imposes terror regime in newly-occupied lands

- Kherson residents share joy of being freed from Russian occupation

- Growing partisan movement of Kherson Oblast now bombs collaborator