Revisiting the blackest pages of history, 18 May stands as a solemn reminder of a genocide not often discussed—that of the Crimean Tatars. Recalling the events which took place between 18 and 20 May 1944 means facing up to a story of horror and untold human tragedy. In one merciless swoop, the Soviet authorities dragged some 200,000 Crimean Tatar civilians from their homes and their loved ones. This barbaric forced migration policy, decreed by Joseph Stalin, inflicted unimaginable pain.

Ten things about the Crimean Tatar deportation you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

Women, children, and the elderly were forcibly deported to Central Asia. The men, meanwhile, were thrust into the inferno of World War II. Around 8,000 people lost their lives thanks to the inhuman nature of their transit, while countless others perished in the brutal conditions of the lands to which they were transplanted, which were often unsuitable for a human existence.

But even as the mass deportation approaches its 80th anniversary, oppression of the Crimean Tatars has returned with a vengeance. While Crimean Tatars were granted the right to return to Crimea in 1989, since 2014 and Russia’s illegal occupation of the peninsula, its indigenous peoples have again been facing the state-sanctioned eradication of their religion, language, and identity – their very right to exist.

In a damning report published in April this year, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights identified repeated patterns of human rights violations committed against the Crimean Tatar people. “The Crimean Tatars have suffered enough,” she concluded.

These violations have intensified and throughout Russia’s occupation and even more so since Russia’s full-scale invasion of the Ukrainian mainland, which has seen many Crimean Tatar men forcibly conscripted into the Russian army to fight their Ukrainian compatriots – a war crime in itself.

This spring, Russia began its 17th illegal conscription campaign in Crimea since the occupation began, with a new law making it practically impossible for those conscripters to avoid service. With an estimated 80 per cent of summons being issued to Crimean Tatars, a group making up only 15% of the Crimean population, it is clear they are being specifically targeted.

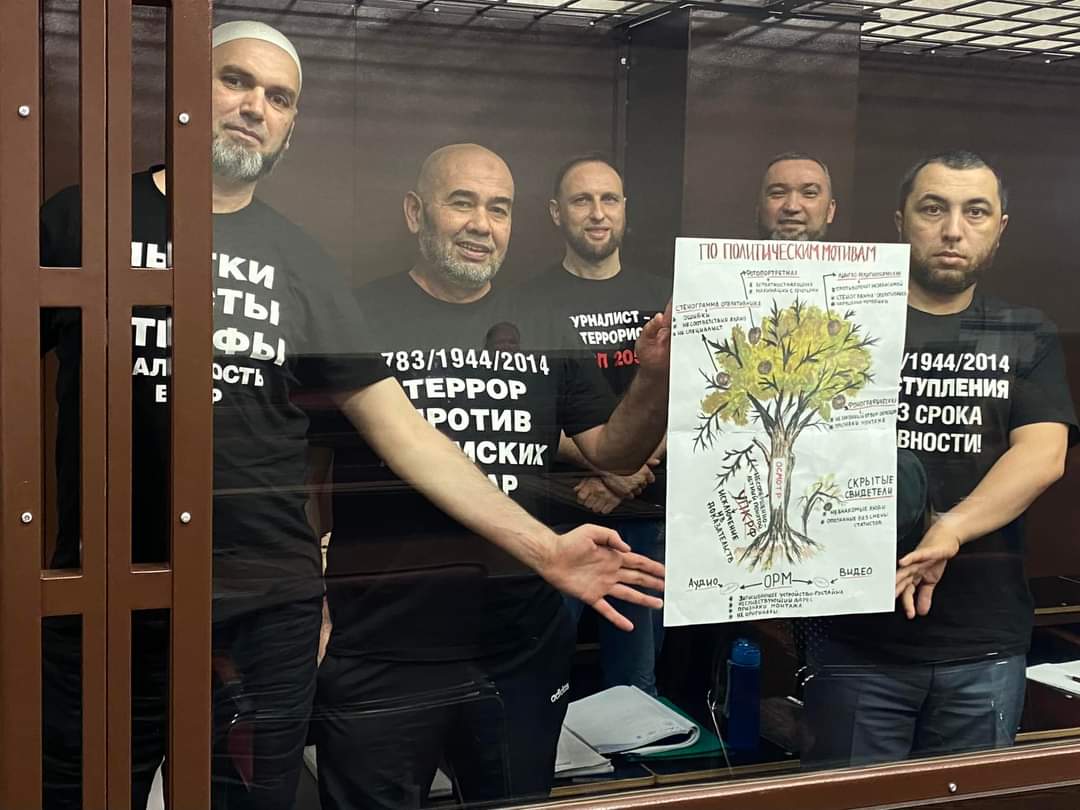

Conscription is not the only area in which Crimean Tatars face persecution. Journalists, religious leaders, and human rights defenders are frequently targeted for politically motivated prosecution. Innocent civilians find themselves accused of “terrorism” on ludicrously flimsy grounds.

Citizen journalist Amet Suleimanov, for example, was one such victim of this campaign. Suleimanov has a serious heart condition which requires surgery. Nevertheless, he fearlessly reported on the persecution of Crimean Tatars by Russian security forces, for which a Russian court sentenced him to 12 years in prison. Considering the absence of proper medical care in Russian prisons and the gravity of his condition, his lawyers reckon that this sentence amounts to a slow death.

Suleimanov’s case is not unique. Last February, it came to light that two Crimeans, one of them a Crimean Tatar, had died in detention after they were denied medical assistance. Both Kostiantyn Shyring and Dzhemil Hafarov had known medical conditions and were left to die by the Russian authorities regardless.

The oppression and ongoing elimination of Crimean Tatars by the peninsula’s occupiers is part of Russia’s plan to turn Crimea – a region known for its scenic beauty and rich history and culture – into a military barracks of enormous scale.

The Port of Sevastopol has housed Russia’s Black Sea Fleet since 1783, but Russia’s military activity has now engulfed the entire peninsula. Its territory and surrounding waters have become springboards for missile attacks on Ukrainian civilians, its hospitals have been commandeered by the Russian military, and its schools have been reduced to tools for the indoctrination of Crimean children into the Kremlin’s militaristic and ethnonationalist worldview.

Suleimanov, Dzhepparov, and many other brave Crimeans have courageously risked their lives in the name of the rights of all Crimeans. But, today and every day, it becomes clearer and clearer that the liberation and de-militarisation of Crimea is imperative not just for the survival of the Crimean Tatar people, but is also a precondition for returning stability to the wider region. Russia’s illegal occupation of the peninsula cannot be allowed to continue.

Related:

- Ten things about the Crimean Tatar deportation you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

- Deportation, autonomy, and occupation in the story of one Crimean Tatar

- I survived genocide. Stories of survivors of Crimean Tatar deportation

- Haytarma: the film about Stalin’s deportation of the Crimean Tatars Russia doesn’t want you to see | Watch online

- Apakay – a song for the Crimean Tatars deported by Stalin

- Russia tortures two Crimean Tatar political prisoners to death