One of the most well-known art phenomena from the ex-USSR, “russian[1] avant-garde” is perceived as a unique combination of spiritually driven art experiments, political engagement, and revolutionary impulse, thus embodying the features that Western society usually sees as the positive side of the mysterious russian culture.

Unsurprisingly, this art became instrumental in the artwashing of the russian regime, on par with “humanistic” russian literature.

All the major modern art institutions, from Museum of Modern Art (New York) to Pompidou Centre (Paris) regularly host exhibitions and events with “russian avant-garde” in the titles, and the books on the subject, popular as well as academic, are countless. However, a closer look reveals a complicated history of a multicultural art movement, deeply rooted in Ukrainian visual traditions, a brain drain to the imperial center, and cultural appropriation.

If you open Google and type “russian avant-garde,” you will find multiple popular articles, exhibition descriptions, and videos, all intended to explain the art phenomenon known under this name to the widest audience possible.

Some of them come from russian sources (like this, for example) and they are engaging and well-written. They will have almost obligatory statements about how social revolution enhanced the revolution in art, emphases on the role of art in creating the new world, and usually more or less the same lists of artists. Malevych[2], Kandynskyi, Tatlin, Rodchenko, El Lisitskyi, Ekster, Burliuk.

And, of course, the adjective “russian” is repeated so many times it becomes ingrained in the reader’s subconscious.

At the same time, typing “Ukrainian avant-garde” will produce a considerably shorter list of links, predominantly from Ukrainian sources. You will, again, find lists of artists – very much overlapping with the ones from the previous search. Some exceptionally curious readers may come to understand that this art and its national affiliation is a topic of hot debate, but nevertheless, leave confused as to whether there is any “right” side in this debate.

To begin solving this riddle let us start with the history of the term itself.

A history of the term “russian avant-garde”

Originally the term “russian avant-garde” appeared in European leftist circles in the 1960s.

Before that, russia was perceived as a country with rich literature but poor visual culture, while émigrée artists like Kandynskyi and Chagall were considered German and French, not russian. That changed in 1962, when art historian Camilla Gray, after miraculously gaining the access to the special secret funds of Moscow and Petersburg museums, published the book “The great experiment: Russian art 1863-1922.”

The discovery of the largely forgotten art treasures of the late russian empire and early Soviet Union fascinated western art lovers. While at first Soviet officials were angered by the publication, soon they came to value the importance of this art in creating a positive image of russian culture and russia in general.

In 1979, the famous Paris-Moscow exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (followed by a twin exhibition in Moscow in 1981) started the triumphant journey of the avant-garde among the general Western public. It is worth mentioning that while those exhibitions were also the first that showed the pieces from the Soviet collections, none of the works from Ukrainian museums were included.

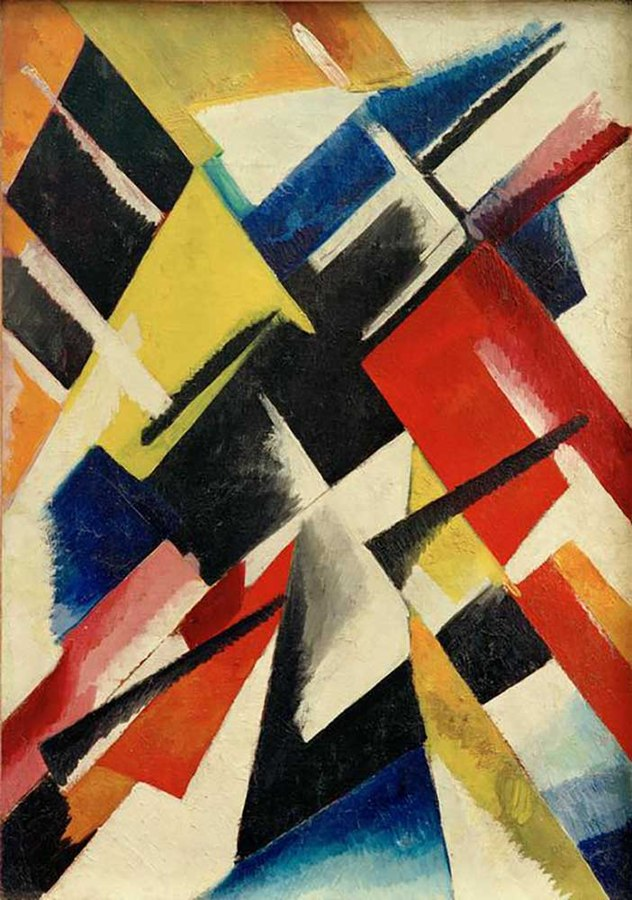

An idea that at least some part of all this mysterious Soviet art can be more accurately described as Ukrainian has been sluggishly circulating among art critics since the 1980s, proposed originally by the French art historian Jean Claude Marcade. Besides introducing the term Ukrainian avant-garde, Marcade highlighted some distinctive features in the works of Ukrainian avant-garde artists: the richness of color, attention to light and space, and excessiveness of forms that could be traced back to the Ukrainian baroque.

Armed with these definitions, Ukrainian researchers started to claim that a large chunk of “russian” avant-garde is actually Ukrainian.

The most passionate proponent of this idea was Dmytro Horbachov, who was the first to open the special secret fund of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, where he worked as a chief keeper of the collection.

However, despite all the hard work of Ukrainian art critics and cultural diplomats, most prominent names are still marked as russian, and it is very hard to challenge the status quo.

For example, in 2017, the large-scale Museum of Modern Art exhibition A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde was met with dismay from Ukrainians, due to numerous inaccuracies and thoughtless listing of most authors as russian (yes, nationality was specifically mentioned in all the exhibition tags). After numerous efforts from the Ukrainian side, famous film director Oleksandr Dovzhenko was reattributed as Ukrainian. However, the attribution of Malevych, Ekster, and many others as russian had not been changed. Neither was Ukraine even mentioned in laudatory articles about the exhibition.

The russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 made this part of pre-Soviet and Soviet art more acutely contested. However, could there really be a final answer whether it is wholly or partially Ukrainian or russian? Especially considering the fact that avant-garde in general positioned itself as an international movement and rejected traditions.

There are several possible ways to define the national affiliation of an artwork. The simplest (and most widely abused) of them are based on the artist’s biography — like her or his ethnic origin, place of birth and/or living, and citizenship. Sometimes (but not in many cases) there is also such a useful tool as a national identity, openly proclaimed by the artist.

Other categories are more subtle, digging more into the artworks themselves than into life events: like how much these artworks were influenced by a specific national tradition. Or how much their production was embedded into the local cultural life — such as it could not possibly appear elsewhere.

Keeping these categories in mind, let us have a short look at the biographies of the avant-garde artists, who make their way into the top 5 the most often.

Kazymyr Malevych (Russian: Kazimir Malevich)

Malevych, whose name is basically synonymous with avant-garde movement, was born in 1879 in Kyiv in a Catholic family of Polish origin and spent his childhood in the Ukrainian province. Malevych also took his first steps in art education in Kyiv, under the lead of Mykola Pymonenko.

Unfortunately, the Kyiv Art School could not provide further education, so most aspiring artists of the time had to choose between either the St. Petersburg Academy of Art or the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. Malevych chose the latter, and for the next three decades, his career unfolded mostly in the two russian capitals.

Among his later collaborations with the Ukrainian art scene, participating in the work of a unique workshop in Verbivka village in 1915-1916 and teaching at the Kyiv Art Institute in 1927-1930 were the most significant.

In the Verbivka workshop/cooperative avant-garde artists teamed up with local embroidery masters, producing experimental designs, influenced by local traditions. Embroideries from Verbivka were exhibited in Moscow in November 1915, thus being the first public presentation of Suprematism.

The Kyiv Art Institute in the 1920s was a vibrant place, where traditional approaches to art and art education coexisted with the most radical ones, so Malevych fit in perfectly. This vibrancy was short-lived, though, with repressions against Ukrainian artists and cultural figures soon putting an end to all the experiments.

Malevych was forced to cease teaching and come back to Leningrad. In 1930 he was arrested anyway, accused of espionage, and threatened with execution. Though released a couple of months after, Malevych was banned from exhibiting and creating “formalist” art. At least he was spared the fate of Mykhailo Boichuk, his colleague from Kyiv Art Institute, executed in 1937.

Was Ukraine something more for Malevych than a place of childhood memories and occasional collaborations?

In various documents and letters, the artist self-identified as either Polish or Ukrainian. Notably, during his interrogation by the KGB, he stated his nationality as Ukrainian. In memoirs, he wrote about his childhood fascination with Ukrainian folk art. Some researchers (Dmytro Horbachov among them) argue that Ukrainian embroidery, wall paintings, and ornaments became a foundation for his famous suprematism. And surprisingly for those who know Malevych through his famous Black Square, most of his art is full of bright colors, as is Ukrainian folk art.

Oleksandra Ekster (Russian: Alexandra Ekster)

A brilliant scenographer and one of the inventors of cubo-futurism, Oleksandra Ekster was born in 1882 in Bialystok (now Poland) in a mixed Jewish-Greek family. She grew up in Kyiv and began her studies at the Kyiv Art Professional School, organized on the basis of the Kyiv Art School.

With her good academic foundation, she continued her education in Paris. There she got to personally know Picasso and plunged into cubism – the latest and most outrageous development in art at the time. While in France, her cubist works were sometimes criticized for their bright colors, unusual for French cubism, but in line with Ukrainian visual tradition.

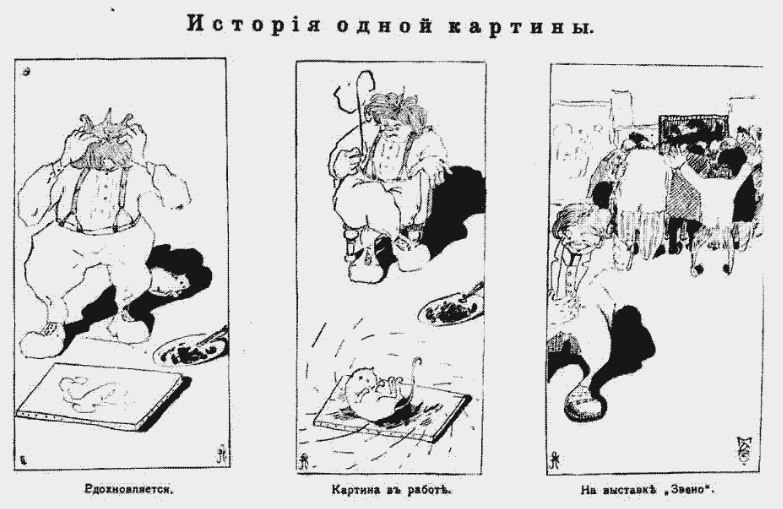

On return to Kyiv, Ekster brought photos of Picasso’s works, which served as inspiration for David Burliuk, who later would be named “the father of russian futurism” (see more on Burliuk below). Together they organized the “Link” exhibition in Kyiv in 1908 – one of the very first exhibitions of local avant-garde artists in the empire.

In 1915-16 together with Malevych, she worked in the Verbivka cooperative, where she collaborated with talented folk artist Hanna Sobachko. In a time when most experimental artists wanted to cut ties with the past, Ekster wove effortlessly both Ukrainian folk tradition and European classics into the new Cubo-futurist art. This elegant and unique combination laid the foundation of work in the famous studio she opened in Kyiv in 1918.

1918 was a bittersweet moment in Ukrainian history: a brief period of independence between two russian occupations.

Despite changes of authority and waves of hostilities, the cultural and artistic life in Kyiv began developing rapidly. Kyiv lost its status as a provincial town that is backward and boring in comparison to Moscow and Petersburg. Oleksandra’s studio was pivotal in this turn from backwardness to the bloom of modern art – all in accordance with her motto “As much free creativity and as less provinciality as possible.”. It was not a traditional painting studio, but rather a place for getting acquainted with new art. Ekster’s studio basically marked the beginning of Ukrainian avant-garde, as many prominent artists, such as Vadym Meller and Anatol Petrytskyi studied and discussed their art and their plans there.

However, all these plans were canceled when the Red Army entered Kyiv in February 1919. Ekster fled to Odesa, but the city was also soon occupied by the bolsheviks. The artist was forced (literally at gunpoint) to make street propaganda posters for May celebrations. Unlike many of her avant-garde colleagues of the time, Ekster never shared Communist ideas. Feeling stifled and threatened under the new Soviet order, in 1925 she emigrated to Paris.

Vasyl Kandynskyi (Russian: Wassily Kandinski)

Pioneer of abstract painting, Kandynskyi was born in Moscow in a family with German, russian and Mongolian roots in 1866. However, he spent his childhood in Odesa and began his initial art studies at the Odesa Art School.

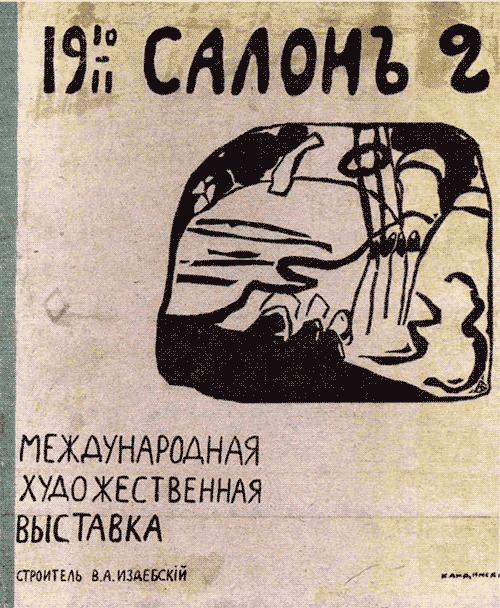

After receiving professional art training in Munich, Kandynskyi maintained personal and professional connections with Ukraine. In 1909, he was among the participants and organizers of the first Izdebsky Salon in Odesa – the first international avant-garde exhibition in the russian Empire. The second Izdebsky Salon in 1911 was basically a personal Kandynskyi exhibition, where the artist originally presented his newly emerged abstract art.

Before WWI, Kandynskyi resided mostly in Germany (where he contributed much to the emergence of German expressionism), while 1914-1921 marked his Moscow period. Initially, he was involved in Soviet cultural life; however, his spiritual approach to art did not really go well with Soviet politics. Mocked and ridiculed by Soviet colleagues and intelligentsia, in the early 1920s the artist took the opportunity and went back to Germany to teach at the Bauhaus.

After Stalin’s turn to socialist realism, all Kandynskyi’s art that remained in the USSR, was prohibited and hidden in the museums’ special secret funds.

Ironically for the artist with German and Russian roots, the German Nazi regime was no kinder to him and his works. Many of Kandynskyi’s paintings and sketches were deemed “degenerative” and publicly burned, while the 68 years old Kandynskyi fled to France.

Davyd Burliuk

Known best as the “father of russian futurism,” poet and artist David Burliuk was born in Kharkiv gubernia in a family with Cossack roots. After studying at the Odesa Art School, he continued his education in Munich, Paris, and Moscow, thus following the typical trajectory of an ambitious Ukrainian artist. A natural organizer, generator of ideas, and socializer, Burliuk participated in most of the very first avant-garde groups, helped to organize exhibitions, and befriended and influenced many other cultural figures of the time, including Kandynskyi and Mayakovsky.

Burliuk’s family estate near Kherson saw the birth of the literary group Hylaea, that in 1912 issued the manifesto of russian futurism “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.” In this manifesto Burliuk, Mayakovsky, and Kruchenykh called to “throw Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, etc, etc off the Ship of Modernity.” After over a century, this famous catchline seems to be acutely relevant again…

Before his emigration first to Japan and then the USA in 1921, Burliuk lived and worked mainly in Moscow. At the same time, he always openly acknowledged his Ukrainian heritage and drew from Ukrainian folk art in his paintings. He wrote in his memoirs: “My colors are deeply national and Ukrainian: orange, green-yellow, red and blue tones are bursting from my brush like the Niagara waterfalls.”

Volodymyr Tatlin (Russian: Vladimir Tatlin)

The first star of constructivism, Tatlin was born in 1885 Moscow in a mixed Ukrainian-russian family, but spent his childhood and began art studies in Kharkiv.

Far from conventional, his biography included running away in his teen years to become a shipboy and later studying in Odesa maritime school. After studying (though never graduating) in Moscow and Penza Art Schools, Tatlin dedicated himself to avant-garde art. As his main rival Malevich, Tatlin taught in Kyiv Art Institute in its golden age of free experiments (1925-27).

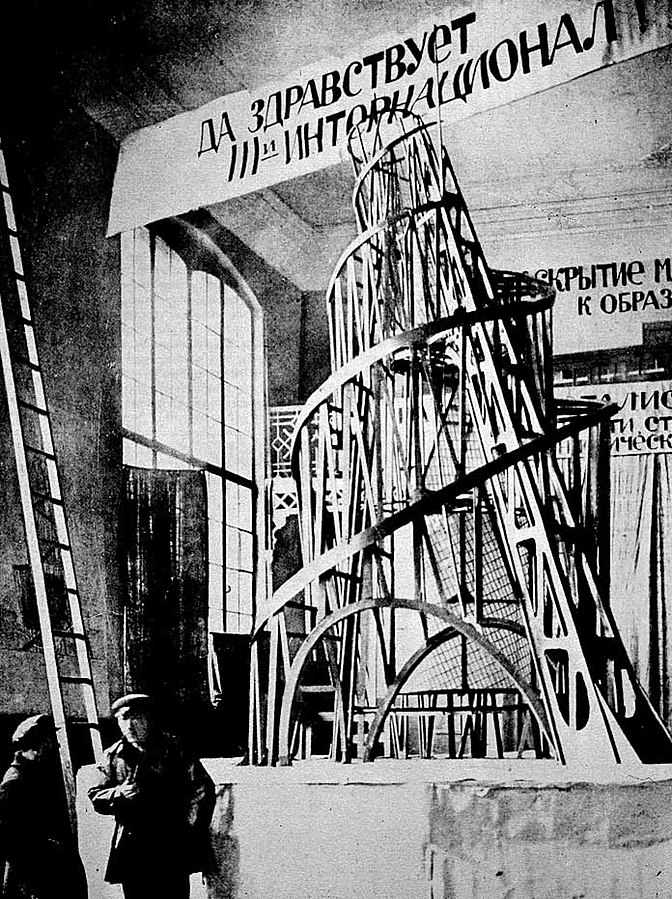

Paradoxically for an art movement that aspired to be embedded to everyday life to gradually shape new humans and new society, Tatlin’s most famous constructions – flying bicycle Letatlin and Tatlin’s tower (project of the Monument to the Third International) – never came beyond project stage.

In the 1930s-1940s, Tatlin was forced to move away from the art spotlight and into the less strictly controlled genres of scenography and book illustration.

Tatlin identified himself as half-Ukrainian. However, there was another link to Ukrainian culture, and quite surprising for an avant-garde artist. The artist played bandura – perhaps the most iconic among traditional Ukrainian instruments, depicted in many poems and paintings. Tatlin even performed in Europe as a traditional bandura player, introducing Ukrainian folk songs to Picasso. Some researchers even see an outline of bandura in Tatlin’s Tower.

Though this hypothesis might seem too far-stretched, if confirmed, it would beautifully reveal one of the most distinctive features of Ukrainian Avant-garde: growing from tradition instead of rejecting it.

Who are these artists by nationality, Russian or Ukrainian?

Besides these top-5, “russian” avant-garde included many artists of Jewish origin, famous El Lissitsky and Marc Chagall among them. Most of them were part of Yiddish movement Kultur Lige (Culture League), founded in Kyiv in the very same pivotal year of 1918. And many studied in the Ekster studio. However, this topic would amount to a separate article.

All these biographies do not provide neat answers to our pending question, whether these artists and their art were russian or Ukrainian. However, they do share a common pattern:

- Talented people of diverse national backgrounds had basically no choice besides studying in the imperial centers Moscow and St.Petersburg and to build their career mostly stayed to work there;

- At the same time most of them spent a significant part of their formation in Europe and were immersed in and contributed to all the European cultural and art trends of the time;

- While not all of these artists openly identified themselves as Ukrainians, their works were often strongly based in Ukrainian visual culture;

- Their creative experiments blossomed in the vibrant atmosphere of large Ukrainian cities in the short pre- and early Soviet period;

- These freedom and vibrancy were short-lived, though. The Soviet regime reestablished talent-drain to the centers, thus dooming Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities to the status of cultural province.

- Avant-garde artists were involved in Soviet propaganda work – sometimes willingly, sometimes by force.

- The revolutionary character of avant-garde soon came into odds with Soviet ideology, and the artists were persecuted by the regime, often forced to leave their homes and emigrate.

- Their works were either destroyed or hidden for decades.

However, after Soviet authorities recognized the potential of avant-garde art to create a “human face of the regime,” the screws were loosened. Russia made avant-garde one of the cornerstones of its international cultural politics. All mentions of complicated identities, diverse ethnicities, and influences of national traditions were erased. It is thus erasure that allowed to claim pre-soviet and early Soviet avant-garde art as russian.

The time to change this is long overdue.

- words “russian” and “russia” are written in lowercase as a sign of protest against the russian invasion of Ukraine. ↑

- as name spellings are an important part of cultural politics, I intentionally use Ukrainian spellings here, which often differ from the ones an English speaker is accustomed to, e.g. Malevych not Malevich, Kandynskyi not Kandinski, etc.

Svitlana Tsurkan is a cultural manager and museum educator, author of lectures on Ukrainian avant-garde

Svitlana Tsurkan is a cultural manager and museum educator, author of lectures on Ukrainian avant-garde

Related:

- A taste of Ukraine’s poetic Renaissance executed by Stalin

- Poetry on fire: a personal journey through Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance

- Slovo House — how a special Soviet apartment block for writers became their prison

- Recovering the forgotten names of the Ukrainian avant-garde