The girl whose gold shoes glittered with paste diamonds stood in the aisle of the plane, her arms outstretched, as the aircraft juddered. I caught her eye and she smiled and headed towards the back of the plane, tentative as a newborn calf. It was 1992 and I was going to visit Ukraine, my father’s homeland, for the first time.

He was taking me to see my aunt who had been repatriated from exile in Vorkuta, a Soviet labor camp in the tundra. She lived in Volodymyr-Volynskyi, a historic town with a silver domed, sky blue cathedral at its heart. Her one-room flat was in a Soviet-era tower block. I saw her many times over the following years and gradually pieced together her story.

During a subsequent visit, I asked her to tell my wife what life in the Gulag was like. She peered into the corridor outside her apartment, then switched off the light in the hall and propped a chair under the door handle. Her voice broke as she described seeing bodies stacked like timber: how whole labor brigades had vanished in the tundra. When we met her friends from the camp in the street they would say “I was at university with your aunt.”The truth is as tiny and clear as the final lacquered figurine at the heart of a Matryoshka doll

My aunt never had children of her own and I wondered if I was perhaps a surrogate son whose Englishness meant that I would always disappoint. We talked about literature and I began my literary translations perhaps seeking her endorsement. However my self-absorbed task was, I now realize, always futile. My aunt simply wanted me to be there and the tirades she delivered were simply manifestations of a love that could not express itself otherwise. Stalin had robbed her of the children and life she should have had.

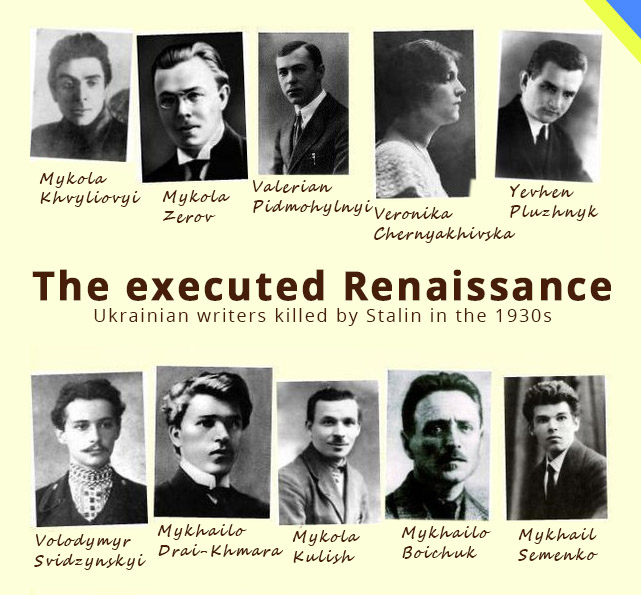

During one of my visits, I purchased a copy of Yurii Lavrinenko’s 1959 tome “The Executed Renaissance.” The book collated work by a whole generation of Ukrainian authors who had emerged during the 1920s. The Soviet government had tried to entrench itself in Ukraine by encouraging the native language. The policy was applied across several non-Russian areas of the Soviet Union.

In Ukraine, where the language had been under attack since the 17th century, the measure resulted in a literary boom.

Ukrainian literature had long been more experimental than Russian perhaps because to write in Ukrainian was to issue a challenge to the empire. The authors who emerged in this period included Tychyna, Bazhan, Svidzinsky, all of whom broke new ground in literature.

The Soviets exterminated the peasantry by means of an organized famine now known as the Holodomor in 1932 to 1933. The country’s artistic and literary elite was also targeted. In both cases, deniable mechanisms were deployed. The Holodomor was applied by a combination of complicated directives and by NKVD officers and party activists who were not privy to its aims.

The country’s authors were subject to a succession of culls using various pretexts.

These began with a grotesque theatrical trial against leaders of a fictitious “League for the Liberation of Ukraine” in 1930. Authors would subsequently be murdered or incarcerated on various ludicrous charges. Oleksa Vlyzko was accused of having fought in Denikin’s army at a time when he would have been ten years old.

The brutally simple ploy of exterminating Ukrainians while pretending to be doing something else works to this day. Many academics are still seemingly bamboozled by events that are simple to understand but wrapped within layer after layer of lies and directives. The truth is as tiny and clear as the final lacquered figurine at the heart of a Matryoshka doll.Ukrainian culture is perceived as a “blasphemous” by some Russians

Lavrinenko’s anthology was compiled in post-war Paris using sources which had been preserved in the diaspora. As you leaf through the book the black and white photographs of the writers embalm their personalities in printer’s ink. Tychyna is lit with an ethereal radiance but looks detached and wary. Zerov’s meditative expression is obscured by the shadows that engulfed him in 1937.Leonid Chernov’s handsome head tilts to one side with a sly grin. You can see the playful poet who danced the shimmy in Ceylon and read Shevchenko to the fishes. The work of these authors is often strikingly beautiful and inventive.

Illustrations for the “Executed Renaissance” anthology by Serhiy Maidukov. Image source: Jetsetter.ua

However, one of the paradoxes of literary translation is that some authors do not travel well. Equally, however, some authors slide effortlessly into another language because they are less experimental in their own tongue (although their work may have other qualities). Lord Byron and Edgar Alan Poe are more lauded in France than they are in England. Auden said that a good poet should be like a valley cheese “local but prized elsewhere.” The very inventivity of some of these Ukrainian authors in their native tongue renders them difficult to translate.

As a 2012 Chatham House paper observed, Ukrainian culture is perceived as a “blasphemous” by some Russians. In their eyes Ukraine is an artificial construct dividing two people; to affirm Ukrainian identity is, according to Joseph Brodsky’s metaphor, to spit into the Dnipro. This message has been internalized in the west which sees Ukraine as reflected in the distorting mirror of Russian narratives. The country is portrayed as having an inferior literature. The Holodomor is depicted as part of a Soviet-wide tragedy. The truth is suffocated within the multiple layers of falsehood and misdirection.

If the western reader can discard the views of Ukraine imbibed from Russia, Ukraine’s culture yawns like Aladdin’s cave before them.

Pavlo Tychyna’s first collection Solar Clarinets (1918) contains a poem Zolotyi Homin (Golden clamour) which anticipates both T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and Ted Hughes’s “Crow.” Gold boats from the mists of antiquity berth on the shores of Kyiv as the bells of Lavra and Sofia ring. The feathers of a vast black crow obscure the sun. The poem captures both the exaltation of Ukraine’s national awakening in 1917 and the violent impulses of the human spirit. Tychyna’s command of Ukrainian is absolute he reinvented the language, much as Paganini remade the violin, as easily as most people breathe.

After 1930, Tychyna would ultimately be compelled to sing praises of the regime while his fellow authors and millions of his compatriots were murdered.

Volodymyr Svidzinsky evaded the bullet and the Gulag until World War 2. On 27 September 1941, he was arrested by the NKVD and accused of anti-Soviet agitation. He and other Ukrainian cultural figures were herded towards the east like livestock. When the convoy was at risk of being surrounded by the advancing German army they were crammed into a disused farm building. The structure was doused in petrol and set alight. For the Soviets, as for the Nazis, people were just resources for the regime or imperfections to be culled. The handwritten manuscript of his unpublished poems was believed to have burned with him.

I kept announcing my modest progress to my aunt. She would listen politely, puzzled, perhaps but I hope she understood I wanted to impress her. However the more I understood about these authors the less I wanted to translate them for personal reasons.

I realized that their story and that of the Ukrainian genocide had lessons for the world today.

This is however, the least important reason for remembering and translating these writers. 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the “October Revolution” and the 80th anniversary of the Great Terror. These events are usually viewed by westerners through Russian eyes. The Ukrainian revolution of 2017 and the mass culling of Ukrainian authors from 1930-37 are concealed within a narrative shaped by Russia. The voices of these writers are as faint as the radio signals from a distant star.

But we need them now. Great literature may be local but it speaks to us of our common humanity. The work of these writers enhances our understanding of the human condition. There are qualities such as Tychyna’s exuberant pantheism which seem uniquely Ukrainian. Yet this poet, like Wordsworth, teaches us the joy of simply existing within nature. Each of his fellow authors can, in different ways, enrich our understanding and experience of the world.

We have heard the voices of Lenin and Stalin who have nothing to say of any value. Let us hear the voices of these writers, their victims, who have so much more to tell us; we will be all the richer for listening to them.

Read more:

- Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance and a kickstarter for one of its modern successors

- Ukrainian translations, Russian oppression, and soft power

- Ukrainians in Russia remember Ukraine’s massacred elite

- Holodomor: Stalin’s genocidal famine of 1932-1933 | Infographic

- Dancing with Stalin. The Holodomor genocide famine in Ukraine

- The Holodomor of 1932-33. Why Stalin feared Ukrainians

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

- The Ukrainian Revolution of 1917 and why it matters for historians of the Russian revolution(s)

- “Rebellious pagan” Ukrainian poet Antonych receives English translation