Newly created communist songs glorifying proletarians replaced the traditional carols; St. Nicholas and the Christmas tree were not spared, either. The novel Soviet New Year was manufactured as a family holiday to replace Christmas, and its allure still perseveres. Nevertheless, the authentic traditions have outlived 70 years of repressions and are undergoing a revival.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, the military occupation of the newly-created national republics, and the subsequent creation of the USSR, Soviet authorities attained political power. They then targeted still popular, so-called “bourgeois,” deeply rooted religious traditions. Obviously, Christmas was one of the strongest cultural links with the pre-Soviet period that was to be uprooted and eliminated.

“Religion — the brakes of the five-year plan” — was the motto of the epoch.

By April 1923, the XIIth Congress of the Communist Party adopted a resolution, “On the Launching of Anti-religious Agitation and Propaganda.” The resolution facilitated the complete eradication of folk customs associated with religious celebrations, including musical works with religious and biblical themes.

Instead of koliady, songs marking the birth of Christ (Christmas carols); shchedrivky and vinshyvky, sung on the feast of St. Basil and St. Melany, which coincided with the New Year, the party proposed communist songs glorifying proletarians. Similar was the fate of St. Nicholas Day, the Christmas tree, and even the symbol of the Christmas star.

For Ukrainians, all of these occasions were steeped in tradition and central to religious celebrations. The examples of rapidly created communist traditions were not only ridiculous but in many cases surreal. They also showcase how terrible and traumatic the totalitarian ideology was. At the same time, inspiring is the fact that the Ukrainian people were able to preserve — and later revive — these musical and religious traditions, despite 70 years of propaganda and repression.

At first, the party was eager to follow Lenin’s recommendation that “it is necessary to replace the religious worldview with a coherent communist scientific system.” Authorities printed more scientific books ridiculing and — by the late 1920s — outright banning religious holidays.

“[The regime] conducted anti-Christmas and anti-Easter campaigns. Children were taught at school that during these holidays crimes take place most frequently. And during lessons, teachers would check that there was no paint from Easter eggs on children’s hands. Along with Christmas, the Christmas tree itself was branded with shame. It was called anti-Soviet, “a priest’s custom,” and religious nonsense. Some still would put it up secretly, behind tightly drawn curtains,” describes Marichka Naboka.

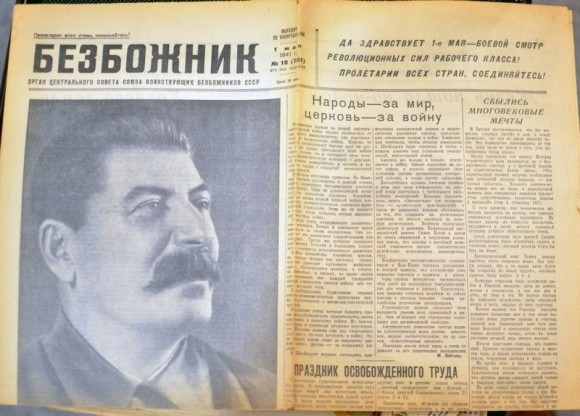

In 1922, the newspaper Bezbozhnik (Godless or Atheist) began publishing in the USSR, followed by the magazine Bezbozhnik u Stanka, meaning “atheist and the workbench,” and many others. In 1925, the Society of Friends of the Bezbozhnik newspaper was transformed into the Union of Atheists.

The USSR also introduced alternative communist rites. For example, Zvizdyny (“Starisms”) as opposed to church baptisms and anti-religious burial rites with a communist star on the tombstone instead of a cross.

Coming to power, Stalin tightened anti-religious policy. In 1929, days off from work were canceled for Christmas, New Year, and other religious holidays.

Regardless of these restrictions, it was not easy to erase traditional rites and rituals that persisted at the community level, even if surreptitiously. Authorities had to change their tactics and did so according to the principle “If you can’t beat them, join them.” But in this case, it was to “lead” them, or more accurately, “mislead” them.

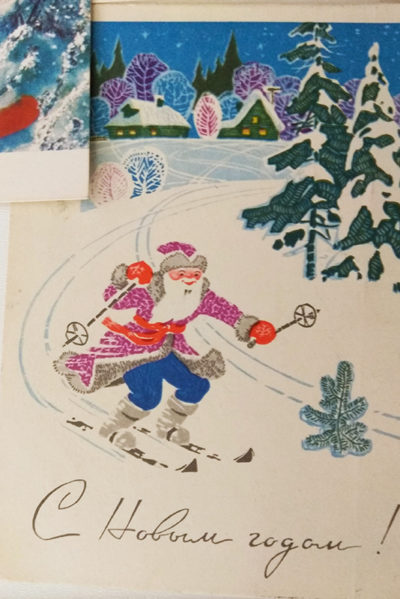

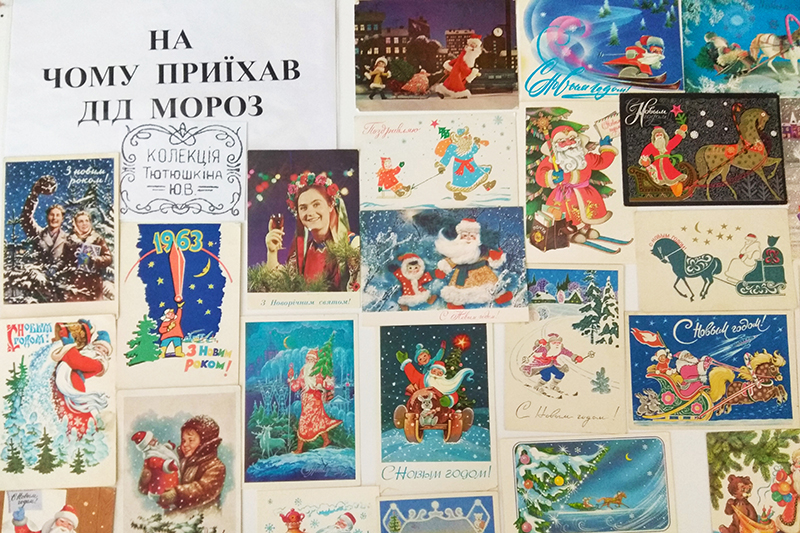

The Soviet New Year spruce tree replaces the (Christian) Christmas holiday tree, while Did Moroz takes the stage instead of St. Nicholas

In the 1930s, it was already evident that simple prohibition and mockery could not extinguish centuries-old traditions. At the same time, after the terror of the Holodomor (1932-33) inflicted by Stalin, along with the dreadful conditions of Soviet life, the regime recognized that they needed to provide some conciliation — give the people something to celebrate, if for no reason than to keep them under control. Thus, they devised a “Soviet New Year” — similar to Christmas in a festive mood, but in place of any religious meaning, communist propaganda was introduced.

The originator of the New Year concept is unknown. However, details were published and popularized by one of the main organizers of the Holodomor. The notorious Pavel Postyshev was the main driver of Stalin’s policy to curtail Ukrainian national identity and a leading member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. On 28 December 1935, on page one of Pravda (Truth), the communist newspaper, Postyshev’s initiative was published as “Let’s organize a good spruce tree for children for the New Year!”

.@hwag_ucmc delves into the story of the creation of Ded Moroz by Communist emissary Pavel Postyshev, known, among other things, for the his role in engineering the Holodomor.https://t.co/wQbtz0vVRc

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) December 19, 2020

Banned a few years earlier as a religious relic, the yalynka (decorated spruce tree) was now rehabilitated from a Christmas symbol to a communist symbol. The order was to prepare “bright New Year’s celebrations that were not dull.” The script for the first New Year celebration was prepared by Sergei Mikhalkov — lyricist of the Stalinist anthem of the USSR and author of popular children’s books — with the help of Lev Kassil, another Soviet author of children’s books.

Officials, enterprises, institutions, the Komsomol (communist youth league), and trade unions zealously reported how many New Year’s trees had been installed and decorated.

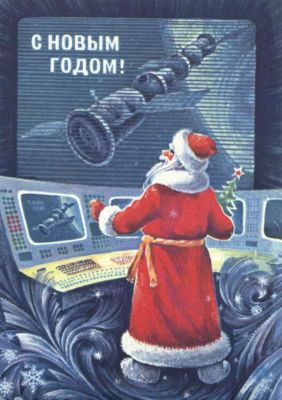

There was a modification, however. The decorative star on the top was no longer the one traditionally associated with Bethlehem, but the communist red star. The New Year’s tree was decorated with communist symbols. Tree ornaments were images of heroes of the revolution, red trumpeters, miners (and later cosmonauts), and of course Lenin, Stalin, Marx, and Engels. And eventually, Did Moroz (RUSS: Ded Moroz) (Grandfather Frost) a secular

figure, replaced St. Nicholas.

As early as 1937, Did Moroz (Grandfather Frost) debuted in the Kremlin palace halls. Like St. Nicholas before the revolution, he brought gifts for children, however, he visited on the secular New Year’s Eve instead of the religious feast of St. Nicholas. The latter had been celebrated on either the 6th or 19th of December — the two dates according to the Julian or Gregorian calendar.

In fact, a new character was a rehabilitated pagan humanized symbol of moroz frost, revamped to fit Soviet ideology. In pagan Slavic mythology, Did Moroz was a strict character who punished evil forces by covering them in frost and whisking away naughty children in his huge sack. But, the Soviet Did Moroz became a jolly person, bringing gifts for everyone and celebrating the New Year with a pint or two.

Snihuronka (Snow Maiden) (RUSS: Snehorochka) in pagan mythology was a beloved child of Did Moroz. In Soviet reality, she became Did Moroz’s worker (mimicking the communist model of a Komsomol scout).

Ironically, Soviet authorities based the characters of Did Moroz and Snihuronka on the 1873 play The Snow Maiden by “bourgeois” Alexandr Ostrovskiy, the play itself arising from Slavic folk tales. The play was mega-popular and possibly inspired pre-revolution “bourgeois” composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov to compose the opera Snow Maiden, and folklorist Viktor Vasnetsov to paint her image. The Soviets borrowed from any number of popular subjects then rehabilitated them to fit the communist ideal.

Although the Church condemned these new atheist and mostly nonsensical celebrations, it could not challenge the official party line.

People continued the tradition of St. Nicholas, bringing gifts to their children on either the 6th or 19th of December. Today, with the fall of Soviet communism, Did Moroz has been losing his appeal year by year, while St. Nicholas has made a strong comeback.

A collection of Did Moroz New Year’s greeting cards gathered by Yuriy Tiutiuskin. Photos: rk.kr.ua

The fate of Christmas carols

Probably the strongest musical traditions during Christmas were koliady, shchedrivky and vinchivky. The communist regime could do little to ban such songs. Instead, it tried to remake them, eliminating any religious reference and introducing yet more glorification of communism. Masterpieces like this appeared:

Добрий вечір тобі, вільний пролетарю!

Нова радість стала, яка не бувала:

Довгождана зірка волі в Жовтні засіяла.

Де цар був зажився, з панством вкорінився,

Там з голотою простою Ленін появився!

***

Good evening to you, free proletarian!

A new unthinkable joy has happened:

The long-awaited star of freedom shone in October.

Where the tsar had settled and took root with the nobility,

There, together with ordinary beggars, Lenin appeared!

Musicologist Pavlo Vashchenko notes that Soviet authorities, seeking to completely quash the spirit of Christmas and its “shameful” religious context, changed not only the lyrics but even the tempo of melodies — instead of the original dolce pastoso (gently, softly) they were performing pateticamente (pathetically, heroically).

“According to censors, this change should have finally removed the ‘religious blunder’ from the minds of Ukrainians,” says Vashchenko.

For example, a pateticamente was recorded in 1930 in the village of Tarasivka in the Kharkiv region as a remade shchedrivka previously sung on the feast of St. Basil and St. Melany:

Щедрий вечір, добрий вечір,

Добрим людям на весь вечір!

Революція вставала,

На бідноту покликала:

Ой, вставай, вставай, голота,

Та рушай-но за ворота,

Будем ворога рубати,

Люд робочий визволяти!

***

Generous evening, good evening,

Let it last for the whole evening!

The revolution was rising,

It called to the poor:

Oh, get up, get up, beggars,

Go through the gate,

We will сhop the enemy,

Liberate working people!

The new communist traditions were contrived and imposed speedily and rigorously. [highlight]While holidays for Christmas and Easter were canceled, the regime introduced 1 January as an official holiday in 1948. New Year became the most awaited holiday for children in the USSR. Not only because of gifts from Did Moroz, but because it was the only non-political holiday, and the family could celebrate together without loud chanting. [/highlight]

Sadly, the ideology probably had the strongest influence at New Year, due to the insidious use of “soft” propagandist power. From the 1970s up to Independence in 1991, special commissions on Soviet traditions were engaged in the development and implementation of new Soviet rites, including approving the release of a series of films, New Soviet Rites.

“The New Year’s menu was decided at the level of the Central Committee of the Communist party. This was the so-called culinary code, which emphasized one of the basic instincts,” explained folklorist and culturologist Olena Chebaniuk.

Naturally, the menu was also influenced by the lack of many products.

[/boxright]

The new communist anti-carols, the red stars, and the Did Morozes, however, did not manage to destroy religious and folk traditions. The party’s official policy of atheism and measures of total control more often had the opposite effect. People simply practiced religious rites and rituals behind closed doors, where opposition to communism thrived.

The lyrics of communist “anti-carols” and other communist impositions, however, are a pained demonstration of the absurdity of the political regime. The political undertones of this cultural association with ludicrous practices influences Ukrainians to this day. Many of the nation’s people still hold a tendency to distance themselves from politics, and perceive the government negatively — regardless of who is in power — even while modern Ukraine is a hard-fought democracy that welcomes participation by the populace at every level.

Read more:

- A Ukrainian Christmas music playlist from Euromaidan Press

- The Christmas mission of the youngest: how Ukrainian scouts bring Peace Light to soldiers on the front-line

- The wonderful world of Christmas as seen through the eyes of Ukrainian artists

- Why does Ukraine celebrate Christmas on January 7, not December 25?

- A Ukrainian composer’s gift to the world of Christmas music

- A Night of Faith: Ukrainian Christmas Eve

- Catholic priest reconstructs Ukraine’s prehistoric Christmas traditions

- The Unknown Ukrainian Carol that everyone knows