The anti-corruption demonstrations in Russia this week – for an interactive map on locations, numbers and arrests, see meduza.io – are supported by 57 percent of all Russians, according to the Levada Center.

They have even attracted comment by Vladimir Putin who says that the problem the Russian opposition has is “not in simply struggling with the powers but showing citizens and voters that the programs [it] is proposing better correspond to the interests of the electorate.”

But precisely because these demonstrations even more than those in 2011-2012 or on March 26 this year are widely perceived as a watershed event in advance of Russia’s presidential elections next spring, they have been the subject of an enormous number of commentaries. Three of them, which consider the consequences of these protests, are especially interesting.

In the first of these, Lev Gudkov, the head of the Levada Center, says that by its harsh response to the demonstrations, the authorities “have contributed to the politicization of young Russians” and thus have made it likely that there will be more protests and that these will be more political.

“As a result of the worsening of the economic situation, the very lengthy crisis and the sense that there is no way out, social tension and dissatisfaction is growing in Russia,” the sociologist says. Much anger is directed at the corrupt nature of the authorities, more for economic reasons than moral ones.

It would be a mistake to see this just as populism, he continues. In fact, the regime’s half-hearted fight against corruption has contributed to the widely held view in the population that the entire government is corrupt. Alexei Navalny has capitalized on this and that is the major reason for his success.

“The portion of Russians who are really dissatisfied with the current regime is not too large but nonetheless notable – consisting of between 15 and 25 percent” who really want to see a change in the composition of those at the top of the state. But the number of such people is “beginning to grow: this is perfectly obvious.”

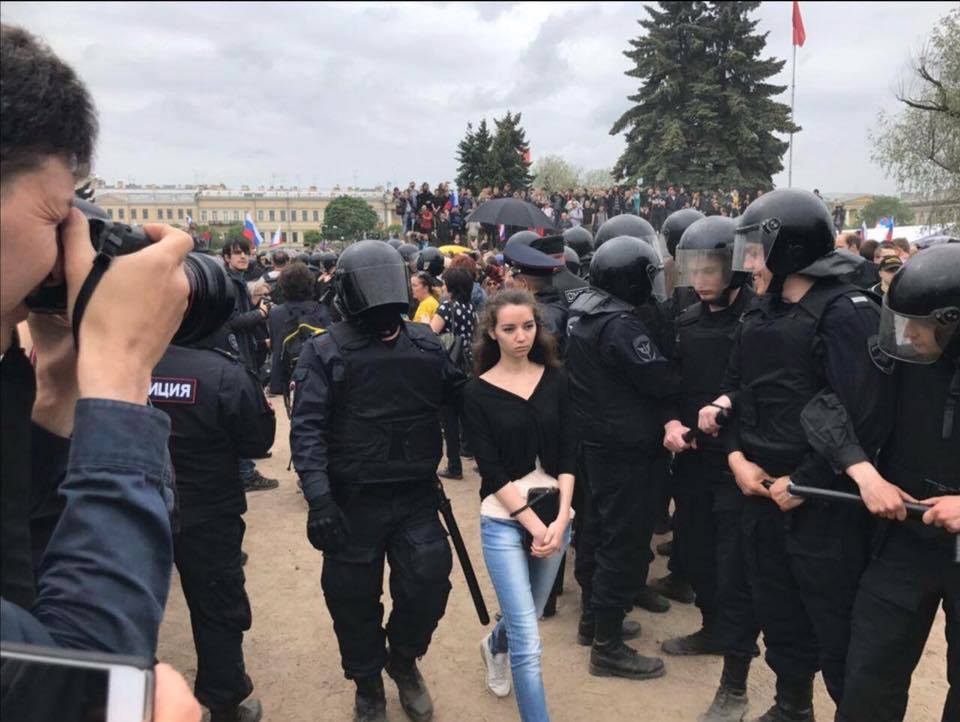

What was especially interesting about this week’s demonstrations was the dominance of young people among the participants. “Because the action was banned, people of older age groups were much less in evidence than usual … By their harsh position of suppression,” Gudkov says, “the authorities are contributing to the politicization of young Russians.”

The Levada Center head says “it’s worth noting that the authorities have quite strong concerns relative to the growth of protest attitudes. They really fear that because massive protests are the only factor which could destroy the system. Because the movement is not egoist and mercantilist, the authorities don’t know what to do” besides using force.

In the second commentary, Moscow political analyst Aleksandr Morozov argues that Navalny by his actions is opening up the political system for “extra-systemic” players but that the relationship of young people to him is more “situational” than many think and that young people could desert him over his perceived authoritarianism.

Russian society at large, Morozov continues, is still behaving in a very “passive” way.

People “recognize very well the risks of entering into conflict with the authorities and they are already frightened … But this atmosphere of hopelessness and pessimism … is not entirely justified.”

And this is “for one simple reason: the high political inventiveness of Navalny and the unpredictability of his political thought.” Because of that, Morozov says, the opposition leader is “constantly broadening the possibilities of the political situation,” as shown by his ability to organize a massive “unsanctioned” protest.

What he will do next is by definition unpredictable, the political analyst says, but his “audience is waiting” for him to “begin to attack not only Medvedev but also Putin. Now, it is still too early to do that, but at a certain moment, it will be already too late.” Navalny has to figure out just when to shift from corruption to the slogan of “’no fourth term.’”

And in the third, Rosbalt’s Sergey Shelin argues that the protests Navalny has organized this year are not just complaints and demands that the authorities do something, “but a struggle for a change in the powers that be.” That means in Russia today, there is something that hasn’t existed for “almost 20 years,” a struggle for power.

That is hardly an equal struggle, of course, but one that prompts the question just “how many divisions” does Navalny have? According to Shelin, what matters now is not so much the numbers of people and places where protests have taken place as the passion that those taking part have brought to them.

He suggests that there are already “three main results” visible.

- First, “it is obvious that in the capitals the authorities were much more afraid this time than in March but that they had prepared for the struggle much better this time around.”

- Second, Russia’s “silent majority” isn’t yet ready to repeat a demonstration and that’s why many took “a pause” now.

- And third, “The June events have shown that a new group of young opposition activists have come into the streets.” Not yet in the millions but already in “many tens of thousands” who are prepared to oppose repression and “the archaic, anti-modern regime” of Vladimir Putin. Thus, Navalny has a serious and consolidated political base. As yet, it isn’t large, perhaps two percent or a bit more. But under Russian conditions, that is a start and something he can build on. And Navalny’s backing will only increase if the authorities try to block him from running as they have up to now. That fact, confirmed this week, makes Monday’s demonstrations a turning point.

The Day of Russia this year “clearly did not become a holiday for the regime.” Instead, it became “a breakthrough day for his opponents. I call it the day of confirmation,” Shelin continues, confirmation that “the Putin era continues, but the atmosphere of the last 18 years has disappeared forever.”

- Russian protest spreads to more than 150 cities

- Ex-Berkut chief suspected of organizing Euromaidan massacre now dispersing protests in Moscow

- Russian protests don’t threaten Kremlin for one simple reason, Portnikov says

- Every meek pointless protest in Russia is a nail in the regime’s coffin

- Even direct costs of Putin’s aggression unsustainable, Pashkov says

- Russian diplomats Chisinau expelled reportedly recruited Gagauz to fight in Ukraine

- Academia again serves state ideology as Russia convicts Ukrainian library head