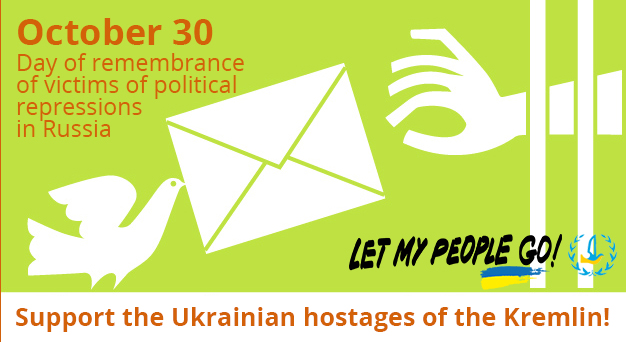

On October 30, Russia’s Day of Remembrance of the victims of political repressions, write a letter to the Ukrainian hostages of the Kremlin!

At least 28 Ukrainians are in Russian prisons on political motives, being charged with crimes they did not commit, facing ludicrous accusations and forged evidence of their “guilt.” They are all part of the #LetMyPeopleGo list.

One of them is the famous Ukrainian Crimean-born film director Oleg Sentsov, who resisted Russia’s occupation of Crimea, and Oleksandr Kolchenko and Oleksiy Chyrniy, who the Kremlin assigned as part of his mythical “Right Sector terrorist brigade,” and Viktor Shchur and Valentyn Vyhivskyi, who sentenced to over ten years for “spying,” and Serhiy Lytvynov, whom the Kremlin’s main propaganda showman Dmitri Kiselyov accused of being a “punisher” who killed 30 men and raped 8 women in eastern Ukraine (all of which is untrue). Mykola Karpiuk and Stanislav Klykh were accused of fighting in the Chechen war 20 years ago, with zero evidence to prove the claim. Stanislav is being driven crazy by the surreal situation and the torture in prison…

A great many Crimean Tatars are also imprisoned, being targeted for their fierce resistance to the Russian occupation of their homeland. Haiser Dzemilev became a hostage because of his father, the famous Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzemilev.

The Crimean occupation authorities is branding Crimean Tatars as “terrorists” left and right, accusing them without any proof of participating in the Hizb ut-Tahrir organization, which nearly only Russia considers to be extremist in the first place. Among the hostages are Ruslan Zeytullayev, Nuri Primov, Ferat Sayfullayev, Rustem Vaitov, Enver Bekirov, Emir-Usein Kuku, Vadim Siruk, Muslim Aliev, Arsen Dzhepparov, Refat Alimov, Enver Mamutov, Remzi Memetov, Zevri Abseitov, Rustem Abiltarov. Many were the sole bread-earners of the family with small children left at home.

The Crimean occupation authorities are persecuting also the leader of the Crimean Tatar Mejlis – Akhtem Chiygoz, and two participants of the anti-Russian demonstration – Mustafa Degrmendzi and Ali Asanov. At the demonstration, which took part on 26 February 2014, prior to the unrecognized referendum with which Russia illegally annexed the peninsula, the Crimean Tatars attempted to block the Russian takeover of the Crimean parliament in Simferopol.

Perhaps, the pinnacle of absurdity is the Russia’s Crimean occupation authorities’ persecution of two Euromaidan activists for purported actions against the Berkut riot police in Kyiv, Ukraine, during the events of winter 2013-2014. The cases of Oleksandr Kostenko and Andriy Kolomiyets appear to be an open retribution.

Like their Soviet predecessors, the modern Ukrainian prisoners of the Kremlin are being deprived of independent lawyers, are being sentenced based on testimonies of “anonymous” witnesses, the court proceedings are being classified, the court refuses to consider the defense’s materials proving that the person isn’t guilty. They are being tortured, and this makes a person agree to any accusations so only the torture would stop. They are being incriminated with wrongdoings they did not commit and sentenced to dozens of years in a modern GULAG.

Why does the Kremlin take these prisoners? They are the bodies that the Kremlin’s propagandists need in order to serve as “living proof” that the tales the Russian population has been hearing on TV – about the Ukrainian “punishers” massacring Russian-speakers in Donbas, about “spies, terrorists, extremists” plotting to take over Russia. After being tortured, these people are likely to confess to anything.

Overall, there are at least 87 political prisoners in Russia, as identified by the Memorial human rights center. Memorial recognizes many Ukrainians from the #LetMyPeopleGo list as political prisoners.

Write a letter to the hostages of the Kremlin!

First of all, join the facebook event and invite your friends.

There are two ways of writing to the prisoners:

(1) by traditional mail,

(2) via the Russian online service RosUznik (not for all the Kremlin’s hostages). In both cases, the message you convey should be politically neutral.

A certain challenge is that the Russia’s penitentiary system delivers to its prisoners only the messages written in Russian. De jure the prison staff has to translate the correspondence in foreign languages, but this is not always the case. Thus you can either try to write in Russian or use RosUznik, and its activists will make the translation.

(Nota bene: the language requirement does not apply to the letters sent to those who are kept in custody in occupied Crimea. These letters are gathered in Kyiv (the address is always: 01014, Ukraine, Kyiv, 22/14 Sedovtsiv Str., Crimean Tatar Mejlis office) and then delivered to a detention facility without the use of Russia’s post service. In this case, you can write you message in English.)

If you’re going to use traditional mail, you’ll find the necessary information in this table at the end of this section (note that sometimes there are slight differences in the English transliteration of the same names from Ukrainian and Russian. Here the transliteration from Russian is applied out of necessity.)

You can use google translate to write something simple, send a postcard, or check out our instructions for writing Christmas cards in Russian for political prisoners- any sign of attention works wonders for them!)

Here is just one example of a template for greetings in Russian:

“Дорогой [here you put the given name of the prisoner, which goes in the middle of the respective record in col. A],

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения. Надеюсь на Ваше скорое освобождение!”

= “Dear [name],

I wish you good health, courage, and patience. Hope you will soon be released!”

Of course, you can ask someone who speaks Russian to translate what you’ve written.

On an envelope, you should write, in Latin letters, an address (do not forget a zipcode) + full name of the prisoner + year of his birth. For instance:

344010, Russia, Rostov-na-Donu, 219 Gorkogo Str., detention facility #1, Primov Nuri Vladimirovich (1976).

It would be helpful if you put inside a sheet of blank paper and a new envelope, because some prisoners want to write in response or simply make their own notes but face a shortage of paper in jails.

RosUznik delivers letters only to the nine Ukrainian prisoners, namely:

Олег Сенцов=Oleg Sentsov,

Александр Кольченко=Aleksandr Kolchenko,

Николай Карпюк=Nikolay Karpiuk,

Станислав Клых=Stanislav Klykh,

Ахтем Чийгоз=Akhtem Chiyhoz,

Мустафа Дегерменджи=Mustafa Degermendzi,

Али Асанов=Ali Asanov

Александр Костенко=Aleksandr Kostenko,

Андрей Коломиец=Andrey Kolomiyets.

Go to the link http://rosuznik.org/write-letter, where you will see a form you should fill. You can easily use Google translation to get all questions on that page in English.

To send you words of solidarity via RosUznik is faster than by traditional mail, as their office is based in Russia. You can ask them to print and send a certain photo (for instance, your selfie with a poster in support of your addresses) along with your letter. If the prisoner replies you, they can send a scan to your email. However, if you want to write to anyone other that the nine listed by RusUznik, please use traditional mail.

History of the Day of Remembrance of the victims of political repressions

On 30 October 1974, the first “Day of the political prisoner” was commemorated for the first time in the USSR at the initiative of the dissident Kronid Lubarskiy and other political prisoners of the GULAG camps in Siberia. The participants all took part in a hunger strike – a common method of resistance among the Soviet political prisoners – and lit candles in memory of the killed innocent people. At the same day, a press conference was gathered at the apartment of Andrei Sakharov, Soviet dissident and future Noble Prize winner, at the same day. At the conference, dissidents demonstrated documents from the prison camps and showed the latest edition of the Chronicle of Current Events, an underground human rights bulletin which was released during 1968-1983 (due to the large number of political repressions in modern Russia, it is now being released once again).

After this, on 30 October each year political prisoners went on hunger strikes, and from 1987 demonstrations were held in Moscow, Leningrad, Lviv, Tbilisi, and other cities. On 30 October 1989 nearly three thousand people holding candles created a live chain around the building of the KGB in Moscow. After they departed to the Pushkinskaya ploshcha for a demonstration, they were dispersed by the riot police.

Ukraine commemorates the day of remembrance of victims of political repressions on the third Sunday of May. First, the date appeared in the country’s national calendar in the late 1990’s and was called “Day of victims of the Holodomor.” Later, a day to commemorate political prisoners was created separately from the day of victims of the Holodomor.