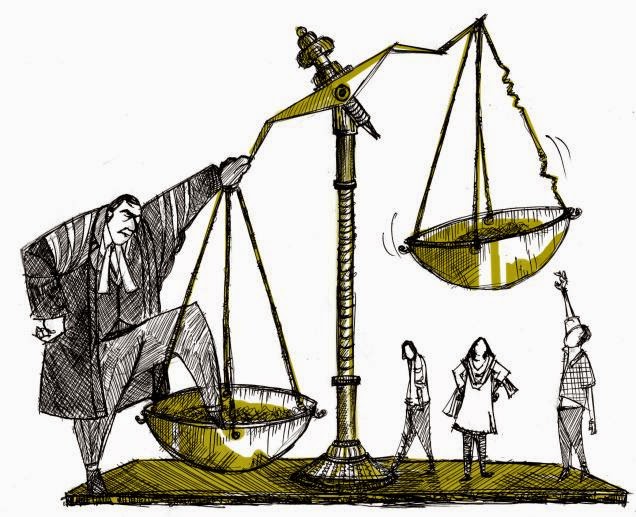

The good news is that the last two years have seen a great deal of change and reform in the civil service and judiciary and consequently both spheres are in a state of flux. The bad news is that the government’s policy of lustration has had very limited effect and faith in the justice system remains extremely low.

As Anders Aslund has pointed out, there is an almost universally shared view that Ukraine’s 10,279 judges and 20,367 prosecutors are ‘all corrupt’.

One poll from The Democratic Initiatives Fund found that 80% of respondents did not trust the judiciary, while nearly 94% said that corruption is widespread amongst judges. Yet in the past two years only 227 judges have been dismissed, some simply because they surpassed the age limit, worked in Crimea or had personal reasons for doing so.

One prosecutor who had worked under Yanukovych and was due to be lustrated managed to get reinstated in just three business days. An anticorruption drive announced by President Poroshenko in October of 2015 was criticized for being cosmetic, with one critic labeling it ‘political theatre, if not selective justice’ and another dismissing it as ‘a Potemkin village of empty crackdowns.’

Moreover, the Prosecutor General’s Office has been completely inert and has failed to bring a single major corruption case to court. The Prosecutor General, Victor Shokin, had long been criticized by civil society groups, Western donors (including the US ambassador) and reformists within the Rada.

The Ukrainian branch of Transparency International blamed Shokin personally for the failure and accused the country’s leadership of “trying to establish control over key anti-corruption bodies in order to make them work in their own interests.” There have been dozens of allegations against key figures suspected of corruption, including Mykola Martynenko, Ihor Kononenko, Borys Lyozkhin, and Arsen Avakov, yet none of them have been pursued by the Prosecutor General.

Consequently, Shokin’s recent forced resignation was welcomed by many but his ineffectiveness and close links to the President underline how far away Ukraine is from having an independent judiciary. An important indicator of the government’s intent will be their choice of successor, for the promotion of a genuine reformer could have a real impact, whereas another living corpse would have the opposite effect.

Come what may, it is important to acknowledge that not all judicial reform has failed.

The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission has approved amendments to Ukraine’s Constitution, designed to ensure judicial independence. The Carnegie Reform Monitor reports that these amendments ‘introduce a three-tier court system designed to improve citizens’ access to justice and the quality of appellate court hearings’.

Moreover, in October the Rada adopted a law which sought to reduce the power of the prosecutors and stripped them of their oversight function – a Soviet throwback which rendered them superior to judges. The law is also supposed to make the recruitment process more rigorous and transparent. Nevertheless, such seemingly positive laws can easily be hijacked by antireform elements who distort them to their own ends.

A member of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group claims that the selection committee designed to hire external candidates as new prosecutors was comprised primarily of Shokin’s cronies. Thus, after the selection commission had finished interviewing candidates, ‘only 3 percent of the successful candidates were outsiders.’ As always, the devil is in the details.

In another piece of analysis Vitaly Kasko, the deputy prosecutor general who recently resigned in protest at government corruption and inaction, estimated that 84 percent of the local prosecutors Shokin appointed were previously district prosecutors under Yanukovych. Similarly, the Rada Anticorruption Committee’s head, reformist Tetiana Chornovil, resigned soon after her appointment because her reform plan ‘Strategy 2020’ had been quickly adopted by Parliament but was then subsequently ‘emasculated by special interests in the Rada’.

Furthermore, on February 2nd the Rada approved the first reading of a bill touted by Poroshenko as a ‘radical overhaul of the court system’. Yet critics say that the bill is largely symbolic and still leaves the president with enormous power including the right to transfer judges from court to court, potentially allowing him to punish or reward judges.

Indeed, the head of the Justice Ministry’s Lustration Department likened the bill to “vetting the old traffic police and then letting the same people patrol the roads”.

Finally, it is clear to all that those responsible for the murders during the Euromaidan are yet to be brought to justice.

Amnesty International states bluntly that ‘those responsible for these violations continue to enjoy almost complete impunity for their actions’. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR) was no less scathing and described Ukraine’s approach to the rule of law as an “accountability vacuum.” In short, judicial reform has thus far failed and the government will have to do much more if it is to live up to its promises.

Related:

- Revitalized and energized: Ukraine’s energy reform success | #UAreforms

- Old faces in courts endanger all Ukrainian reforms | #UAreforms

- Mixed expectations for Ukraine’s new government | #UAreforms

- Making a miracle: Ukraine's untapped economic potential | #UAreforms

- 3 reasons to be optimistic about Ukraine’s battle for better bureaucracy | #UAreforms

- Why Ukraine needs a technocratic government | #UAreforms

- Oligarchs: good old buddies who own Ukraine | #UAreforms