Article by Euheniia Martyniuk, Alya Shandra

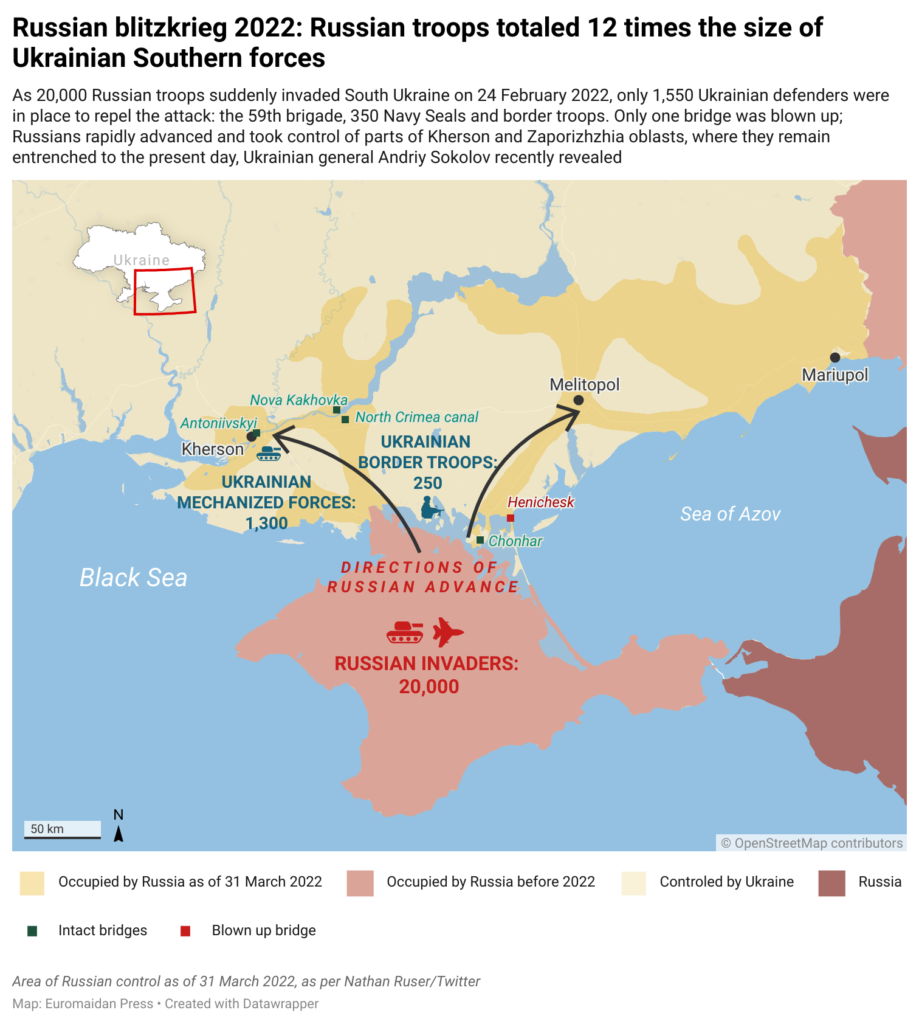

Unanswered questions have fueled debate among Ukrainians since Russia’s rapid seizure of Kherson and advance on Mariupol early in the February 2022. Because the bridges stood intact in Chonhar, one of the two road and rail connections of the occupied peninsula with southern Ukraine, Russia’s invasion was swift and it promptly occupied vast swaths of land that Ukraine is currently struggling to regain.

Why didn’t Ukraine blow up the bridges to Russian-occupied Crimea? Who cleared the minefields at the Chonhar isthmus? Despite intelligence warnings, Kyiv seemed unprepared to defend the South. With no official explanation to what enabled Russia’s rapid invasion from Crimea, speculations flowered online: did a traitor enable this on purpose? Major General Andriy Sokolov, who commanded Ukraine’s Southern forces, now addresses these controversies in an interview with Ukrainska Pravda. He does not appear to blame himself and paints a picture of stretched resources and chaos, suggesting that the Ukrainian leadership was not taking threats of an impending Russian invasion seriously.

1,500 Ukrainians against 20,000 Russians

Major General Andriy Sokolov revealed to Ukrainska Pravda that Ukraine lacked adequate forces in the South at the start of Russia’s invasion. The military’s defense plan called for four brigades of 1,000-8,000 troops each, but there was only a single brigade in the region when the attack began.

“The Southern grouping operated on a rotational basis, meaning that personnel would arrive and then be replaced by others. Overall, there were approximately 1,500 combat-ready personnel at the time of the invasion,” Sokolov explained.

The general noted a particular shortage of artillery in the South. Two artillery units were away training near Kyiv and combat engineers were exercising in Khmelnytskyi Oblast when the invasion began.

At first, the Russian forces encountered just three minimally manned Ukrainian strongpoints: one at the Chonhar bridge and two checkpoints. Ukraine’s leadership had weighed reinforcing the South but lacked sufficient resources, according to the general.

“[Russia]concentrated its forces along a large stretch from Belarus to Crimea. We did not have enough forces, as we needed to keep troops in the Joint Forces Operation area [in the Donbas region], cover Kyiv, cover the north, Slobozhanshchyna [Northeast Ukraine], the Kharkiv direction. I believe that this is exactly why there were not enough forces,” the general stated.

According to Western estimates, Russia had 190,000 troops at Ukraine’s borders on the eve of the invasion. The number of Ukrainian defenders is not easy to determine. According to various estimates, Ukraine had some 130,000 active troops, but not all of them were located at the border. Roughly 30,000 most experienced soldiers were in eastern Ukraine, engaged in a conflict with Russia’s proxy Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics” that had been simmering since 2014.

These 1,550 troops were wildly insufficient to defend the territory, Sokolov admits. For simply “stabilization operations,” meaning periodically repelling Russian sabotage groups, he needed at least two. A plan for actively defending the territory called for four brigades: two mechanized or combined arms brigades and two territorial defense brigades. The two former brigades had been formed, but no command was given for them to be assembled and transferred to Sokolov.

Effectively, the general met the Russian invasion with only one brigade.

Sokolov had reported about the scarcity of Ukrainian troops in the south to commander of the Joint Forces Serhiy Naiev, but no results followed. This is despite Russia acting “exactly as predicted” in Ukraine’s wargames, which all had a Russian invasion from the south.

Russians used artillery to clear the minefields

On the first day of Russia’s invasion, Sokolov remained at his command post monitoring aircraft flights, clinging to the hope that it was merely a provocation rather than full-scale war until the last possible moment.

“At around 4-5 AM, we witnessed a large-scale aircraft takeoff in Crimea. We counted them and lost track around the 30th plane. Initially, they circled over Crimea, presumably organizing into a combat formation. There was a glimmer of hope that they might return to their airfields, as had happened on previous occasions. However, they dispersed over the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, initiating a massive missile launch,” Sokolov recounted.

Initially, the Russians struck at the checkpoints leading into occupied Crimea and used rocket artillery to clear the minefields. The Russians knew about their locations, as everyone in the region did. It couldn’t be otherwise – to protect civilians from mine explosions, warnings were prominently displayed everywhere.

The Russians’ second strike hit almost all military sites in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts.

Ukraine had few prepared defensive lines: the Kherson Oblast, unlike the conflict zone in Donbas, did not have a special status, and building fortifications would require alienating the land from its owners.

A dozen bridges connect Ukraine to occupied Crimea. Only a few of them were destroyed – notably, a Ukrainian soldier in Henichesk did so at the cost of his own life.

“Bridges should be demolished before the enemy arrives, not when it is already in place. This should be done in advance of the enemy’s approach and potential shelling of the bridges. This way, there is a greater chance of achieving a 100% success in the mission,” explained the general.

According to Sokolov, the bridges at the Crimea border have been mined since 2014. With the bridges deeper into Kherson Oblast, things were different, although they were also important. For example, the bridge over the North Crimean Canal connected Kherson with Henichesk, and the bridge over the Kakhovka Canal crossed the Dnipro River. Those bridges were initially mined and guarded in 2014, but as forces shifted to the Donbas, the number of troops in southern Ukraine decreased. Sokolov explains that the mined canal bridges were eventually cleared due to a lack of personnel to monitor them.

The ammunition from the bridges was stored nearby at the Chaplynka depot. After the war broke out, Sokolov promptly gave orders to place the ammunition back under those bridges, and succeeded in destroying some. Yet, the Russian soldiers managed to advance via many others.

Despite the looming Russian invasion, no orders were given to mine the roads to Crimea. And at the start of the invasion, Russia jammed the radio communication of Ukrainian troops, forcing them to rely on unstable means such as Whatsapp messages, further complicating organized defense.

“I realized the war had started when I witnessed a massive missile strike on our units. However, there was still the possibility that the enemy might not initiate the ground phase immediately. Instead, for the first day or two, they could have launched concentrated air and missile strikes. Such methods of operation do exist,” the general reminisced.

Russian forces were entering Southern Ukraine with 25 battalion-sized tactical groups comprising approximately 20,000 personnel. Additionally, the Russians held a substantial equipment advantage.

“That’s a lot. It includes both artillery and all the equipment they have. Plus, there’s an air component with around 140 aircraft, 60 helicopters, and their naval assets from the Black Sea Fleet,” said the general.

On the initial day of the invasion, Ukrainian air defenses remained unresponsive, granting the Russians undisputed air superiority, Sokolov recollects. Furthermore, he points out that the defense strategy for the Dnipro River needed to be more adequately coordinated. For instance, the bridges in the Kherson Oblast, such as Antonivskyi Bridge and the Nova Kakhovka dam, were left unmined. Sokolov explains that his responsibility extended solely to the east (left) bank of the Dnipro, as he lacked the forces to defend the west (right) bank simultaneously.

“Generally, we should have, without relying on our small contingent, created some kind of strategic line of defense there, at least in pockets in the area of the Antonivskyi Bridge and in the area of the Nova Kakhovka dam. This should have been done in advance, before the war,” Sokolov says of Ukraine’s poor defense planning in the region.

The 59th Brigade was responsible for Kherson and was in combat at the Antonivskyi Bridge. However, no dedicated brigade was stationed in Melitopol, prompting Sokolov to seek reinforcements for the city’s defense urgently. He decided to transfer one battalion from the 59th Brigade to Melitopol. In addition to this, support arrived from a National Guard regiment, patrol units, and the 110th Territorial Defense Brigade. The Russian forces were stationed near Melitopol, and Ukrainian defenders effectively targeted them with the Uragan multiple rocket launcher system. While Ukrainian National Guardsmen entered the city, they ultimately couldn’t maintain control.

“The local authorities in Melitopol were in disarray, and it seemed anyone could have assumed control, given the absence of organized resistance or defense. The enemy subsequently entered Melitopol, leading to the withdrawal of the National Guard units from the city,” recollects the general.

According to Sokolov, the Ukrainian military command had been preparing for a potential Russian attack from the South. This specific scenario had been practiced in all wargames, and the Russians followed the anticipated script precisely. On one front, they captured bridges and river crossings over the Dnipro, and on another front, they seized Melitopol and Mariupol to establish a land corridor to the occupied Crimea.

However, the general believes that Ukraine lacked the forces and means to repel this attack.

“We were embroiled in a major war while operating within a peacetime framework. We had no additional military formations at our disposal. We had to make do with what we had. Let’s break it down: at that time, there were 12 brigades in the Joint Forces Operation area [in the Donbas region], 5 in each tactical group, plus reserves. We were also responsible for securing Kyiv, Kharkiv Oblast, and Chernihiv Oblast,” the general elaborated.“The command allocated as much as it could to the south,” Sokolov is convinced.

In hindsight, the situation could have been better managed through early mobilization and a more efficient organization of territorial defense, Sokolov says. For instance, territorial defense units could have been strategically deployed to border areas under the guise of training exercises.

Sokolov also noted his awareness of the criminal case related to the defense of Southern Ukraine. He has already been questioned in this regard, albeit as a witness. Nonetheless, the general is confident that the principal evaluation of these events will ultimately come from Ukrainian society.