Russia masterfully promotes divisions in its neighboring countries, supports internal opposition to weaken them, and then allegedly becomes a defender of the Russian minority, sending military support to bolster Russia advocates.

In this very manner, it supported the breakaway of Moldovan Transnistria in 1991; conducted an offensive against Georgia and occupied South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008; and occupied Ukrainian Crimea in 2014. Finally, Russian officers, soldiers, military equipment and weapons, and financial backing helped the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) to wage war in eastern Ukraine since 2014.

What can those attacked by Russia, i.e., other European states as well as internal Russian opposition do to stop the aggressive behavior of Putin’s regime? We asked 10 intellectuals from post-Soviet states, including Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Moldova, Georgia, and the Baltics.

This is the last of the four-part series, 30 Years of Freedom. The series is based on the comments of our speakers, including extracts from their published essays:

- Part One. Demolishing monuments not enough to destroy post-Soviet nostalgia, but property rights help | 30 Years of Freedom, p.1

- Part Two. The post-Soviet oligarchies and how they shaped national state politics | 30 Years of Freedom, p.2

- Part Three. The end of the Soviet Man: How ex-USSR states forged their national identities | 30 Years of Freedom, p.3

- Part Four. How to stop Russia’s wars in post-Soviet states? | 30 Years of Freedom, p.4

Moldova

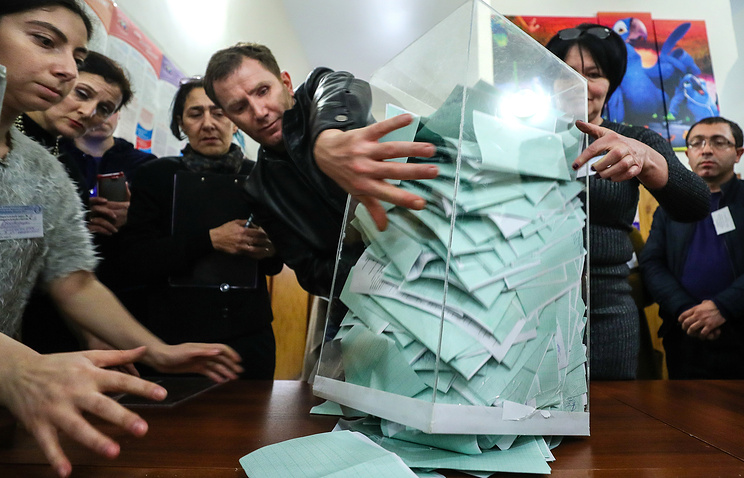

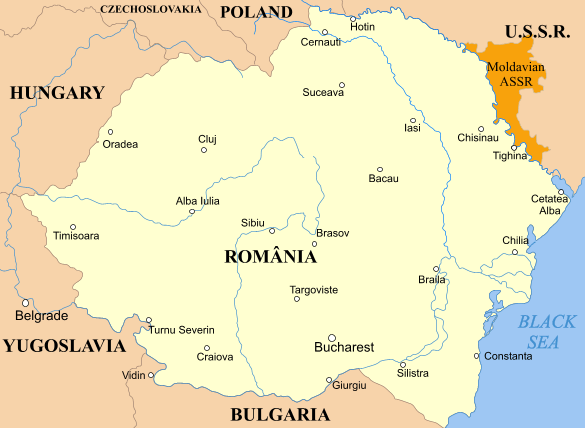

Unlike most of Moldova, which was part of Romania in the interwar period, Transnistria was an autonomous Moldovan republic within the USSR stretching along the banks of the Dnister River. In 1990, the 14th Soviet Army [Russian army after the fall of the USSR] was stationed there. Russian military personnel actively participated in the 1990-1992 war of self-proclaimed Transnistria against Moldova, training and supporting local militia while at the same time declaring neutrality. After a ceasefire was reached on 21 July 1992, the war became a frozen conflict, with the leverage of Russian influence.

Negura: We have this frozen conflict, but frozen in a sense that nobody cares about it. People are moving from one bank to the other quite freely, we don’t have real conflict in this regard.

Moldovan authorities and Transnistrian authorities are provoking public opinion by forbidding any kind of routine action; for example, forbidding access for Transnistrian vehicles to Moldova because of Transnistrian vehicle registration, or Transnistria forbidding access for Moldovan farmers. So we have these kinds of isolated political skirmishes, but we don’t have active or strong large-scale conflict.

It’s not comparable to what happens now in Donbas and especially not to what happens in the Caucasus — for instance in Armenia and Azerbaijan, or in Abkhazia and other post-Soviet enclaves.

About the Russian army — yes it is present, but it doesn’t create problems for people’s everyday life. Right now, we have polls asking people what are the most important problems in Moldova. Transnistria is probably the fifteenth listed — not the main one.

I don’t know whether that’s bad or good. Maybe it’s good that we don’t have massive collective violence, but perhaps it’s not very good that we keep tolerating the Transnistrian regime which is not legitimate. Also, there is a handful of oligarchs who are actually leading this territory according to their own interests and carrying on all kinds of dirty activity.

Solution

I don’t know if there is any political power interested in solving the Transnistrian issue. Yes, we have a popular discourse saying that Transnistria is our territory so we have to get it back — expelling the Russian army.

At the same time there is a kind of political realist one saying that we don’t need Transnistria because these people are not really Moldovan citizens, although many of them do have official Moldovan passports. They are educated and socialized in the system that brainwashed them, and they are completely different from us. These realists fear that if Transnistria joins Moldova then a so-called “Transnistriazation” of Moldovan politics will occur.

And there is a third faction that thinks we should focus on Moldova, solving problems within Moldova of top-level corruption, mismanagement and bad economy, and then we will try discussions with Transnistria. And perhaps when we become more developed economically, socially and politically — more democratic — then we will be able to propose something positive to Transnistria.

But now when someone goes from Chisinau [Moldovan capital] to Tiraspol [Transnistrian main city] or from Tiraspol to Chisinau, they would not easily realize which part is more developed. It is quite the same. And sometimes people who come from Tiraspol say that the streets there are cleaner and there is more order.

Ben: What does the physical border look like between Transnistria and Moldova? Is there a fence or soldiers and what more?

There are soldiers and checkpoints. We have something like a border, but you pass through this border quite easily. At the border you just fill in a form because you are passing through. There are some soldiers protecting the [Moldovan] border from Transnistria. People don’t feel this border is really difficult to pass. When you have to go from Chisinau to the Odesa Oblast in Ukraine, then sometimes you have to pass through Transnistria because this way is shorter and then you just pass through.People don’t feel this border is really difficult to pass.

Ben: What is the biggest victory and the biggest disappointment of the last 30 years in Moldova?

The disappointment consists of two parts. One is that we didn’t have proper politicians or political elites that were honest, successful, or competent with good intentions. The other is that I’m quite disappointed with civil society which was closed-in, quite isolated from society as a whole, and quite dependent on Western funding. It did not care about attracting people at the ground level.

The biggest achievement? Perhaps liberty, but a relative one within a society with such poverty. It’s as if you are free to buy everything in a supermarket but you don’t have money. You can benefit from all this freedom and all these rights but you don’t have real capabilities. But I do have hope that this will change, and I really hope that this change will occur quite soon.

Erizanu: I’ve been there several times and in 2011 organized a forum for young people living on both sides of the Dnister, and in Gagauzia. This was one of the first times a youth forum was held.

In my work, I come across Transnistrian artists as well. Communication does take place, but obviously their life is very different because of the elites that create very different frameworks. With censorship in place in Transnistrian television and all Russian media, people are exposed to a different ideology — a mentality shaped by the government.

Ben: What about identity issues? What language do people in Transnistria speak?

60% are native Russian speakers and 40% are Romanian native speakers. There is the issue of the rights of Romanian people in Transnistria — the government in Transnistria has tried to limit instruction, using Romanian as little as possible. It’s quite difficult for Romanian speakers there.

Young people mostly leave Transnistria and either go to Moldova to study or to Ukraine — Odesa, for instance — or to Moscow, or to Western Europe. With what I know from Transnistrian artists, the country itself is waning because of depopulation.

Ben: Is Russian popular contemporary culture present in Moldova, such as TV series produced in Russia and broadcast in the Russian language, as well as Russian pop music, etc.?

We still have television and radio that broadcasts Russian films, TV shows, and music. The big-budget TV programs produced in Russia really attract people — high-quality entertainment. We also have local Russian theaters. I would say we are kind of mixed, very influenced by both Romanian culture, Russian culture and Western culture — all three. In the capital city, about half of the citizens speak Russian and half speak Romanian. In the countryside, the largest part of the population is Romanian speaking.

Baltic states and expansion of EU and NATO to the east

Voren: Russian culture is not popular today in Lithuania. It might be to a certain degree, but solely among the Russian minority. However, there is no ban on Russian music or people coming from Russia. Two years ago, we organized a conference in Kaunas called “Building bridges — thoughts about the other Russia.”

I think there is an understanding that Putin’s Russia is not the whole of Russia. But at the same time Russia is the threat. It’s felt all the time and it’s clear that Russia is trying to destabilize the country.

I’m now organizing a conference about 30 years of diplomatic relations between Russia and Lithuania. It is very interesting because the treaty that Russia and Lithuania signed on 29 July 1991 is the treaty where Russia acknowledged that it occupied and annexed Lithuania.

It’s the only treaty of that kind for post-Soviet states. Of course, Russia doesn’t want to remember this treaty. It’s very difficult to find good speakers from Russia for the conference, because they are also scared of what is happening and they are scared to speak out.

Ben: Why is it so difficult for other post-Soviet states to join the EU and NATO, as the Baltic states did as long as 17 years ago?

The situation in which you are now is quite different from that of the Baltic countries in 2004. Internationally, the Baltic states were considered to be occupied by many countries and in the process of reinstating their independence. Joining the EU and NATO was only a matter of time for them. In the case of Georgia, Ukraine and others, it is the Western fear of being decisive and taking steps that Russia won’t like.

[bctt tweet=”Robert van Voren: There is a general problem in Europe which was not there when the Baltics joined the EU. There is a complete lack of vision in the EU, no European spirit, no feeling that we are doing something together.” username=”EuromaidanPress”]The EU has become a very bureaucratic machinery which reacts passively rather than positively, and I really think the EU needs to reinvent itself. Moreover, the fact that it doesn’t dare to do anything regarding Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova is because of the internal corrosion that first needs to be dealt with. I think this is something that needs to happen first before Ukraine can really hope for membership in the EU. The foundations are rotten. This is truly a big problem.

Liekis: The main issue here is that everybody looks at their own interests. It means that the interests of the French, the Germans or whatever nation usually direct their policy toward Russia. Their interst towards Russia is usually greater than their interest in the Baltics or Ukraine. This is a matter of size. They have particular interests in Russia. Put simply, they can’t say that they support country X because they like it. Their interests are about reality. The reality and issues with Russia are usually considered much more important than the issues with Ukraine or with Poland.

Usually, we disregard the element that a particular entity has its own specific selfish interests. Often, we think about the world as being governed by certain principles based on values. This position is often the position of the weak side. Because a strong element usually speaks openly about their interests, and their laws or principles come from this position.Usually, we disregard the element that a particular entity has its own specific selfish interests

The problem with Ukrainian or Baltic politicians is the same. Usually they think that we have to go with policies based on values — like democracy, human rights, etc. But look at the United States.

[bctt tweet=”Sarunas Liekis: Regaring the US and Ukraine relations, the US often refers to corruption in Ukraine. But their greatest ally in the Middle East is Saudi Arabia. Is it a democracy? For sure not. An autocracy of the worst kind.” username=”EuromaidanPress”]But Saudi Arabia is the greatest ally of the US Very often we don’t think in these categories. For example, how does the US deal with South and Central America, like Guatemala, Mexico, etc.? How do they deal with all kinds of human rights abuses in South American countries, like Columbia? Columbia is an ally, Venezuela is not.

Let’s take even Ukrainian and Turkish affairs. Ukraine is a democratic country. Is Türkiye a democratic country? Come on, I don’t think so. But nobody in Ukraine has a problem making good deals with Turks because they support the Crimean issue in terms of technology transfer, etc. So, Türkiye is an ally. But is it democratic, is it a proper country in terms of values? I think Türkiye is not very different from Russia in this regard, but the interests of Ukraine are violated by Russia, not by Türkiye.

Ben: What can be done about this?

It takes time to get the balance of powers in certain regions and certain geographic areas. It takes time, it’s not a matter of transformation.

[bctt tweet=”Sarunas Liekis: EU member Romania is not very different from Ukraine, when we speak about rule of law, corruption. But Romania is in the EU and Ukraine is not.” username=”@EuromaidanPress”]In 2008, Georgia and Ukraine were speaking about NATO membership. But the opportunity was lost because of the Georgian/Russian war, and the Americans decided to stay away. So, it’s a matter of power to take a risk.

The Russians are challenging the Americans right now. Are the Americans ready to go into conflict? I don’t think so, when you look at Biden’s decisions: Nord-Stream, Afghanistan, and other decisions.

Look at Afghanistan! 20 years of war, 1 trillion dollars spent, hundreds of thousands of people killed, and it finally ends up with the Taliban again in power. So, where are we right now?

I think everybody is balancing right now, trying to establish a new configuration of power interests. Because of that, this stage is very dangerous, everybody can make moves in one or another direction. This is an element of instability. It seems that Americans are not ready to push, but they are the only power who have the potential to do so, unlike Europeans. The EU is a soft power, but without America they are not able to do anything for all kinds of objective reasons. They lost this hard element in the policies. They cannot threaten in any way.

But also, regarding Ukraine, we should look at transformations in Ukraine, such as not trying to please somebody, because it doesn’t matter if you are pleasing or not. This is like men and women for example. It doesn’t matter whether you please, you try hard, it doesn’t work. She thinks that you are a “shmuck,” you know. If you get more power as a country, better organized, collect more taxes, acquire greater military power, etc, then everybody will start paying attention.

The Baltics are a very different case. They are very small, nobody made a big deal about them. It was simply a small window of opportunity and they just slipped in. Had they lost this window of opportunity, they might be like Belarus right now, despite all the rhetoric of being pro-Western.

In the Baltic countries there was a clear political consensus on what they needed to do, and it helped them to slip in.

Belarus

The biggest victory of the last 30 years is that despite strong Russification, despite Lukashenka, who is the Soviet kind of leader, despite a huge Russian informational presence in Belarus, Belarusians have managed to evolve their own national identity and statehood.

Both of these have become a major value for the majority of Belarusians, and this seems to be irreversible. This is a very important new trend in Belarusian history, because Belarusians had traditionally a very weak national identity — only the intelligentia, the elites, maintained one. That’s why the fact that Belursian national identity is now held nationwide is a very important change — a tectonic change.

On the other hand, the biggest loss is the ongoing brain drain, because this is not the first wave of emigration of young talented Belarusians. Hundreds of thousands of talented Belarusians have left because of Lukashenka’s mismanagement of the country and this is the most problematic trend strategically, because it deprives us of all forms of potential progress — in politics, economy, industry, culture and other areas.

Georgia

Both were supported by individual volunteers from Russia. Although a ceasefire was declared in 1992, the war flared up anew in 2008 with direct involvement of the Russian regular army. As a result, South Ossetia and Abkhazia became self-declared unrecognized republics backed by Russia.

Jishkariani: I don’t think we have to compare the conflict in 2008 and 1919. These are two totally different circumstances and situations.

In 1919, the situation in South Ossetia was highly supported by local Bolsheviks and those situated outside the borders of Georgia. But it didn’t have a clear ethnic formation because, for example, many Georgians were among those Bolsheviks supporting rebellion in South Ossetia.

So the ethnic component in this conflict existed, but we have to underline that there was also a struggle between two political parties, such as the social democrats and Bolsheviks. At that time, the ethnic configuration was totally different. Many Ossetians supported the First Georgian Republic, and demonstrations were held in favor of Georgian state policies in South Ossetia as well as in Abkhazia.

Regarding 2008, it’s quite clear this was definitely an occupation. We had Russian forces just 100 kilometers outside of Tbilisi. Many villages were being occupied by Russian forces. It was the same as what is happening now.

Ben: Who actually are Ossetians? How similar is their identity to Georgian or Russian, and why can Russia so easily manipulate them?

Even in the 19th century, under the Russian Empire, Georgian-language newspapers were published and Georgian-language schools existed in Ossetia. Political elites communicating in Georgian existed — including in South Ossetia. Georgian nationalists who tried to construct a new Georgian nation had been active as of the 1860s and 1870s. Ossetians were quite well integrated into part of the Tifliyskaya Gubernia, which comprised most of the ethnic territories of contemporary Georgia. Ossetians knew the Georgian language well and their intellectuals were part of a Georgian-speaking sphere. Children graduated from Georgian schools. Local Bolsheviks launched uprisings against the Georgian democratic republic in 1919. Subsequently, the region became autonomous during Soviet times and Ossetian separate identity was actively promoted and manifested. (Read more on the Georgian and Ossetian identity in the following article).

Russia

I think and hope that the process of USSR disintegration has stopped. States surrounding the former Soviet Russian republic became independent, as was prescribed in the Soviet Constitution. The Russian Federation should seek its own ways of self-organization. It should become a state, like the US, not dangerous for others (because people want dangerous states to fall apart), but a state which helps to save stability. This is not just the US

[bctt tweet=”Andrey Zubov: The biggest democracy on Earth is India. All main religions are represented in India, all races. And it is still a united democratic state. This is an example for Russia.” username=”EuromaidanPress”]I hope and I do everything possible as a politician so that Russia becomes this kind of state friendly to its neighbors. I’m happy that I can say this once more to the Ukrainian people. Our party, from the very first day of the occupation of Crimea and war in Donbas was speaking out decisively against the occupation of Crimea and war in Donbas. We adopted necessary formal statements, they are all on the party’s website and everyone can read them.

The position of our party hasn’t changed at all. We think that the first steps of the democratic Russia — perhaps even before the first democratic elections are conducted — should be to leave Donbas, get out of Crimea. Of course, those people who want to move from Crimea to Russia should have this possibility, while those who want to remain in Ukrainian Crimea should have this option as well.

We will appeal through the European Community so that principles of international cohabitation are applied to Crimea, and in that way Russians there will have some guarantees. But we don’t have the right to hold Crimea for a single day. This is a question for Ukraine, its desire to be a civilized state and solve its own issues without foreign interference. It is not our task. We came by force and violence and should go away without any conditions. The same is about Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria. Our party doesn’t raise any question about whether we should do this.

The other thing, I will say this sincerely, is that the majority of Russians will not agree with our position and it’s not clear how it will evolve later. So, it’s better to solve the issue of Crimea before the first elections, because after the first elections it may be harder to solve it.

Ukraine

Currently, Putin tries both hard and soft approaches to return Ukraine into its sphere of influence. And the best response is asymmetrical — not by counterarguments, but by actions. To build a Ukrainian state that isn’t affordable for Putin’s Russia would be the real victory.

Europe means a lot of different things but contemporary Europe means above all the absence of war. As for Ukraine, I believe that Ukraine is European because it has managed to reconcile with the Poles. Whatever we may say about the current relations between Poland and Ukraine, generally speaking, the Polish-Ukrainian reconciliation has taken place. You can’t imagine a war for Lviv or Przemyśl now. And that was the reality a few decades earlier.

Unfortunately, that is not the case with Russia. There are many Russian politicians and intellectuals who claim that Ukraine has territories that must belong to Russia. If they thought otherwise, there would be no war in Donbas and no annexation of Crimea.

How far will the EU spread to the east? The key issue is Russia.

The Russian state views a sovereign Ukraine as evidence of its own inferiority. Currently, Russian wars are about the imperial arrogance of Russia, which is largely refuted by the fact that Ukraine and other states have chosen their separate ways. Many Russians think this way:

“They are almost like us. Why do they have to separate from us? We did so much for them! We are such a great world civilization, we gave the world culture and everything else! And then suddenly Ukraine separates.”

In fact, the separation of Ukraine is evidence that Russia is a weak civilization. An independent Ukrainian state wounds Russia’s pride. This is one of the reasons why Putin has recently published his new article about the alleged “historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” and has even ordered to translate this article into Ukrainian.

Interestingly, when Russia feels that Ukraine is pulling away more and more, its language becomes softer.

In my recent commentary on Putin’s article, I affirm my concern that Putin is forcing us to play this game, and we play it according to his rules. We respond to his arguments with our counterarguments. But actually we can defeat Putin by acting in some other way. Not by arguments/counterarguments, because I am convinced they will never convince any of us.

[bctt tweet=”In fact, Ukrainian response to Russia should not be in words but in action. Building of better institutions. To do what Russia can’t afford. Russia cannot afford to have open political competition, the existence of opposition, independent courts, and an efficient economy.” username=”EuromaidanPress”]Everything they do have is just an attempt to mask a bad game with good words. Our best response to Putin now would be the emergence of independent courts in Ukraine. For me, the main difference between Ukraine and Russia is not in the language, but in the different way of organizing society and power.

Former Canadian Ambassador defines “top 10 mistakes” in Ukrainian reforms

Why post-Euromaidan anti-corruption reform in Ukraine is still a success