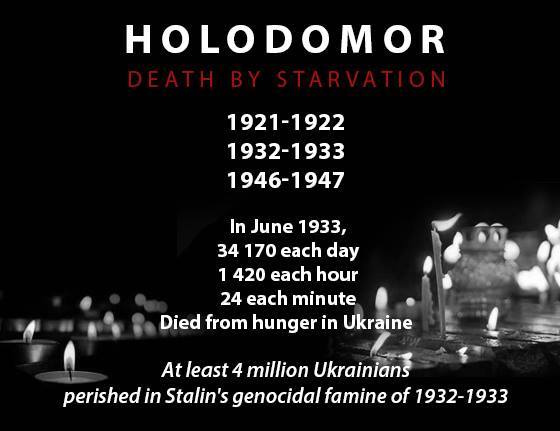

The Kalnysh family survived the Holodomor. Thanks to their father’s skills and his partial collaboration with the communist totalitarian regime, nobody died in the family, and occasionally they even helped their neighbors survive. The story of Semen Kalnysh and his family shows how people on the ground faced a difficult existential choice: become an accomplice to the crime to survive, or remain human in spite of everything. After all, the Soviet regime forced neighbors to become enemies and snitch on each other, and some “activists” caused more damage than was ordered from them. In 2006 the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted the law that recognized the status of the Holodomor in 1932-1933 as a genocide. This decision was a result of the UN Convention of 1948 on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In 2010, the Kyiv Court of Appeal pronounced the sentence in the case of committing genocide by the higher authorities of the communist totalitarian regime, and Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Pavel Postyshev, Stanislav Kosior, Vlas Chubar, and Mendel Khatayevich were found guilty. These seven people artificially created the conditions for the famine in order to exterminate a part of the Ukrainian nation. When the authorities were making criminal and murderous decisions, local people, right to the heads of the kolkhozes and activists, were facing a difficult existential choice, which was to obey, to become a participant but, obviously, to survive; or to disobey, to help, and to be punished. The history usually conceals the names of these people, since there were too many of them, that’s why they are usually called in general, the Executors. The Kalnysh family lived in the village of Obukhivka in Dnipropetrovsk Raion of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. On 15 February 1927, Semen Panfylovych was born there. He was the third, the second-to-last child in the family of wealthy villagers. He received his surname Kalnysh from his grandfather, Vasyl, who was a Lithuanian and came to Dnipro with his three brothers to get a job at the plant. In contrast to his brothers, he didn’t become a worker, but married a local village girl and went to work on the land. Semen’s mother Natalia was from a family which had 10 kids. Her father, Semen’s granddad, was claimed a kulak in times of the Soviet occupation. Fortunately, he was not deported to Siberia or Solovki. “My grandfather had oxen, five or six horses, a few cows, around fifty sheep, goats… It was a rather rich household at that time. And he had the land of eleven hectares in the steppe and a private plot of land of two and a half hectares. He gave everything away to the kolkhoz. To be precise, back then it was SOZ (or TOZ), joint cultivation of land.”The Kalnysh family owned a windmill before collectivization

TSOZs were the early forms of collectivization that involved collective possession of the cultivated fields.

At the same time, equipment and cattle were the private property of each member of the association, though they were used jointly. The equipment was bought communally and was a collective property.

Despite the strong agitation directed by the authority of the USSR, Ukrainians mainly did not support the idea of joint use of the land and agriculture equipment. Though Soviet propaganda constantly focused on the increase of the quantity of TSOZs, in reality, less than 5% of farms were their members. The majority of Ukrainians wanted to work alone, to be the owners of their land.

That’s why at the end of the 1920s, the communist totalitarian regime abandoned the idea of TSOZs and started complete violent collectivization, forcing people to join the kolkhozes. The property of those who disagreed was taken away, they were called ‘kurkul’s and were usually deported from Ukraine without a right to come back.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();

Semen recalls that, though both of his parents were from wealthy families, at the start the life of the spouses Nataliia and Porfyrii was rather difficult.

“At first, we were rather poor. Then, in the NEP times (the so-called New Economy Policy of the 1920s – Lenin’s temporary return to free market economy), when private property was allowed, my father decided to build a windmill. There were seven of them in Obukhivka. Ours was the seventh. And we started to live a wealthy life. My father was a skillful, creative man.”

The household of the family was quickly enriched with horses, sheep, and different poultry. This became possible due to their mill.

Authorities destroyed all mills in the village, millstones were banned by law

“My father was a party member,” Semen Kalnysh says. “For two callings, he was an assessor in the people’s court. My father was a teacher when there came a decision to eliminate illiteracy in Ukraine (‘liknep’, the elimination of illiteracy, a governmental campaign of the 1920s aimed to popularize literacy among the population, a part of ‘Ukrainization’ policy – Ed.). Hence, he accepted the Soviet authority naturally, as well. Although he still didn’t go to the kolkhoz.”

The fanaticism and falling into the trap of the Bolshevik propaganda, a hope to improve the financial situation, an attempt to keep yourself and your loved ones in safety, taking a side of the occupation regime, an absence of understanding of the real state of things and their possible effects. And each situation, each story, the destiny, and the choice of each person is in this case individual.

“The head of the local government in the village came to our house. His last name was Traktorov, he was not local, not from Obukhiv. My father was just ill, and he was lying in bed. And Traktorov said, ‘Panfil Vasylovych, your mill’s time has come.’ They came, pulled it down, yet took nothing away. They brought down other mills and looted everything from them, including the millstones. There was such a law. Traktorov wasn’t guilty. It was an order from a higher authority. We made little grindstones from the mills. We called them ‘kruporushky’. There were seven mills in Obukhivka. The last one that fell was ours.”

The government outlawed possessing millstones, patrol brigades confiscated grain

The farmers brought their grain to the mills – it was usually several mills in each village – to grind it at miller’s in flour. During the implementation of the unbearable grain procurement plan by Ukraine in 1932, an appearance of the villager with a sack of flour at the mill meant that he had a store of food. It was inevitably followed by the searches in the household and the confiscation of the food “on account” of the plan.

That’s why people were forced to use the home millstones, which was hard labor. However, according to the “Five Ears of Grain Law,” even that kind of grinding was regarded as a crime. To avoid it, the patrol brigades often took away and destroyed the home millstones during the raids in the houses.

The patrol brigades did other types of “party work,” in particular, they were engaged in collecting the grain for the grain procurement plan during the Holodomor. In other words, they searched the houses. Semen Kalnysh recalls,

“The grain procurement was performed by the local government. They were local. They were voluntary. They didn’t receive any payment. Officially, they didn’t. They were volunteers, activists. And they did their job voluntarily. There could be two, three, four people in one brigade. They had these ‘shchups’ and shields. They searched and took everything away. They took away the maximum amount of grain. And they took away all the other food, as well.”

Semen recognized some of the activists since they were his fellow villagers.

“For example, Vaniusha was the son of the richest man in Obukhivka. But he was the poorest in the family, although his father supported him, gave him a cow. And Vaniusha started to go with the activists in times of the Soviet authorities. Although they didn’t receive any payment. Maybe they interested the people. I think it was an order from the higher authorities to search the houses. Maybe it was an order from the regional instance. Maybe it was from the instance of the district. And all of them knew the result.”

The head of the Kalnysh family was a communist, that’s why their household wasn’t searched

Semen says that the activists didn’t come with searches to the Kalnysh family after the accident with the windmill. Maybe, the reason was that our hero’s father was a party member. But further on, the situation in the village intensified. It was hard to tell apart a friend from an enemy.

“There was so-called Foma Tsapko, and he had eight sons and two daughters, in total, he had ten children. He also took two orphan boys and fed them,” Kalnysh says. “So, he buried eight poods of millet at night. And his neighbor saw this and denounced him. And they came to him with these shchups. They ordered him to confess. He didn’t confess. They found the grain; they found it and took it away. And he was deported to Siberia. He spent 25 years in jail, and when he came back, he was not allowed to stay in his house, not even in Obukhivka. So, he stayed in Kalynivka, 25 kilometers from here. But later on, he was allowed to come back after all.”

Promised to get their confiscated food back, some villagers denounced their neighbors

The activists often were “tipped off,” which means that fellow villagers snitched on each other as in the mentioned case. These immoral acts were provoked and encouraged by the criminal regime that first took away all the food, and then promised it in exchange for the information. However, they didn’t always keep their word. Dividing and setting people against each other was a communist method.

“All the grain was taken away in 1933. Nothing was given to kolkhoz members, not a gram. There was a decision made, to take it away. But the people buried, hid everything. And these people with shchups searched voluntarily, by denouncements. They didn’t go to the ones who had a higher authority, who could defend. They went to the man who was more humble, who was denounced, and had something hidden. I think this way, regarding the people’s talks, my parents’, grandfathers’, and grandmothers’, the locals did terrible things here.”

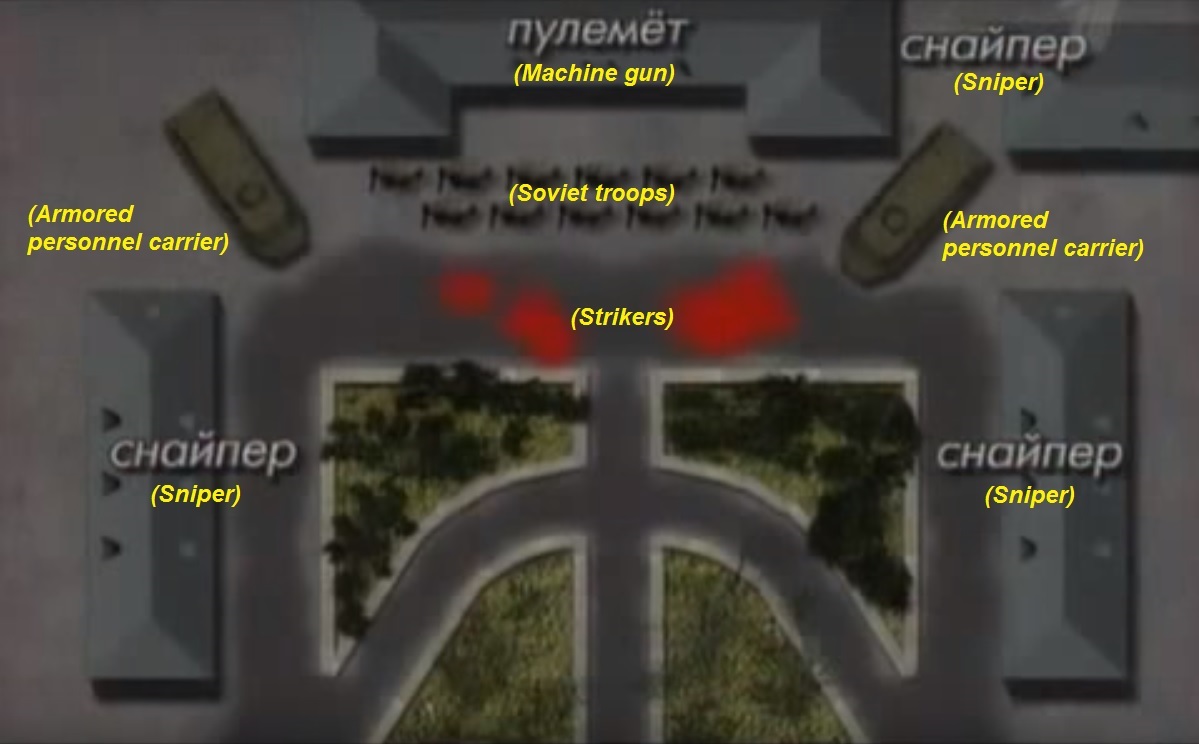

Some peasants rebelled, Red Army suppressed their mutiny

Certainly, the villagers resisted the repressive measures,

“People gathered in a few families and drove these people away. The activists went away, but even more people came back in anger. It means they did their job.”

Communist activists also destroyed churches without orders from central authorities

However, these terrible orders came not only from the higher authorities. Sometimes the local activists took their own initiative.

“That’s what surprises me. We had the greatest church in the district; the same one was only in Novomoskovsk and Obukhivka, built with no nails. But the church was destroyed. And it was an initiative of the local government. There was no order to fall down the church. It means that they did it to curry favor, to account, to make a report to the higher authority.”

During the anti-religious campaign, almost all the churches in the district were destroyed. They took them apart, and the materials were used to build barns, cowsheds, and other farming buildings.

“People didn’t let them demolish the church. It was destroyed only on the third attempt. There was already a militia, and it was put up to support it. They said that the church is not appropriate, that it’s opium. The activists, the followers of the destruction of the churches, were climbing up, demolishing everything, and then taking it apart. There was only a base and a fence left from our church.”

The precious things kept in the church were saved from the Soviet activist robbery by the village chief, Voroshylo. He collected everything, the icons, and other relics, at his place, hid them, and after the Second World War, returned everything to the unfinished house where a local community organized a clandestine church secretly from the occupational authorities.

The priest of the church in Obukhivka managed to escape the repressions since he wasn’t local and used to come from the city every week. According to Semen’s words, after the destruction of the church, the atheistic activists violently shaved the priest’s beard and threatened him with death if he would come back to the village. Since then, no one has seen him.

Villagers survived thanks to grain stored by field mice and fish that suffocated under river ice

The father of Semen Kalnysh refused to join the kolkhoz, even though he was a party member. The windmill brought enough of an income, and additionally, the father was hunting and fishing. The massive searches and dekulakization did not have an impact on the Kalnyshes’ household.

And during the Holodomor genocide, they even managed to help neighbors and relatives.

“There was our neighbor, an old man, Osakii, who lived in the house next to ours. He had a family, a grandmother, and three children, two sons, and one daughter. They were swollen from hunger. And my father helped him, he also helped other people, his brothers and sisters. For example, Yevtykhii was the youngest out of the neighbor’s children, he came saying: ‘Auntie Natalia, give me at least something! Auntie Natalia, give me at least something!’ He said it to my mother. I told you, we stored something. So, in particular, my family did not suffer a lot from hunger.”

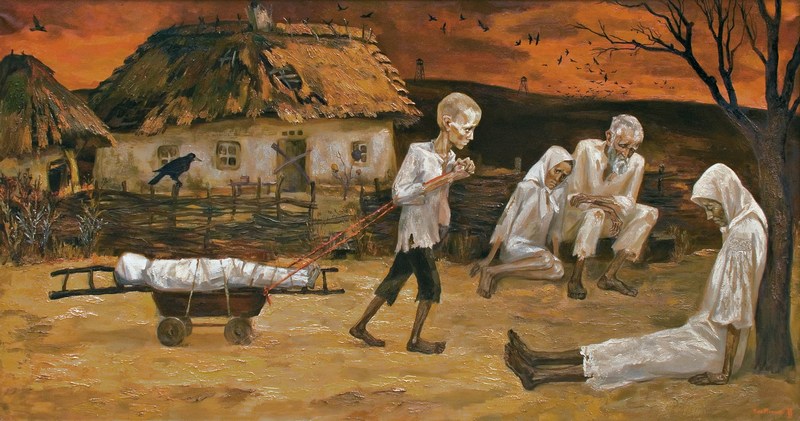

Kalnysh recalls that the general situation in the village was quite hard. People were mainly saved from starvation thanks to “myshaky,” which means the grain stored by the field mice for winter by covering it with the hillocks of soil.

The villagers went in the fields, gathered these hills of soil, and sieved the ground at home, searching for the little grains in the dust. This happened in the winter of 1933 when it suddenly got warmer for ten days and the snow melted.

“There was an accident. There was a family living two kilometers from us called ‘Tsapy.’ The mother and three daughters. In winter, they went to search for ‘myshaky’, but the mother didn’t reach the place, she died on the road because they were far too swollen from starvation. The Kukuriky family also starved. The Tkaches were starving.”

Besides the fields, the citizens of Obukhivka went to the lakes. There were eight of them in the neighborhood. Here, under the ice, the fish couldn’t breathe, and people cut it from the ice and ate it.

Semen Kalnysh recollects that the villagers didn’t refuse to eat anything in despair from hunger. This way, when the horse died in the kolkhoz, it was brought away to the field and taken apart in pieces. People were also eating cats and dogs.

“For example,” Kalnysh continues. “The Osakii family lived nearby, and Yukhym lived beside them. He lived more or less well, he worked at the plant. He had a big dog and a cat. So, Osakii’s father and his sons Yevtykhii and Ananii went in three and took away this dog. They brought it to their place, killed it, and ate it. But they returned the cat. This is how Yukhym and Osakii became enemies for life.”

Semen and his father hunted for gopher meat; his uncle sacrificed himself to save his wife and son

In spring 1933, a lot of gophers appeared. Semen with his father often went hunting them.

“My father used to tell me, ‘Senia (a short name for Semen), take a bucket and a landing net. We went. The sun was shining, and they were near the holes. By two or by one. You come, pour the water, and they jump out, you catch them in the landing net. I say I have never eaten tastier meat than these little gophers.”

This shows that Semen’s family had a hard time in 1933, contrary to his assurances in the opposite as he was only six at the time and probably wasn’t told everything. And the tragic story of Semen’s uncle contributes to this point;

“My mother had a brother Nil. He had a very beautiful wife from Poltava and a five-year-old son. My grandfather helped him; he gave me a half-sack of rye. They divided it, they counted each grain. How many grains are there in a handful of grains? Fifty? Seventy? That was their ration. When only ten kilograms were left, Nil was off to who knows where, leaving the grains for his wife and son. They survived. And he died. My mother and their youngest sister, Kharytyna, took a carriage and brought his body. He was buried here. His name was Nil Svyrydovych Spodynets.”

The Holodomor wasn’t the only famine of the Soviet era

“1921. There was a severe famine in Obukhivka as well,” Semen recalls from the memories of his mother and father. “My parents, and also our neighbors, Samsin and Rodeon, took everything they had, the horse, brychka (a light carriage), kozhukhs (traditional Ukrainian fur coats), valianky (winter footwear), pieces of riadno (a traditional kind of bedsheet) and went away to Poltava region. There was more or less a good harvest. And they brought 10-15 poods of grain from there.”

Patrols arrested people who tried to find left-over grains

Semen Kalnysh remembers that during the mass artificial famine of 1946-1947, severe punishment for collecting the ears of grain was the same, since the “The Five Ears of Grain Law,” enacted in August 1932, did not lose its power until (not accidentally!) 1947.

“In 1947, we collected the harvest. And one man with a teenager son gathered ears of grain on the stubble field. They were caught by the patrol. This man was very arrogant, he didn’t accept the Soviet authority, although he worked in the kolkhoz. And the father and son were imprisoned for eight years! In the neighboring village, the people were also driven out of the stubble field. The local government, the patrols, were special people chosen from the active members of the authority, from the kolkhoz, from the directions that went to search for the people. But could they ‘not notice’?! They could. Or that was such a case. In Kalynika, the patrol caught people and insisted on their imprisonment. Though it wasn’t necessary to notice them. It wasn’t necessary…”

Semen collected the ears of grain as well, though the people were driven out of the fields. But they waited in the forest until the patrol would pass by and came back again to collect. The grain was thrashed in the evening, and they could have about three kilos of grain. There were one and a half buckets of grain a week.

Son of a communist, Semen chose to never join the Communist party

Semen Kalnysh, a son of a party member, survived the Holodomor and the post-WWII mass artificial famine of 1946-1947, but never joined the Communist Party. He studied engineering and worked for decades in the Dnipro Machine-Building Plant that produced equipment for the objects of anti-aircraft and anti-missile defense. It is hard to imagine how in that situation, Kalnysh, who wasn’t a party member, was allowed to manage more than 10,000 engineers and technicians of the munition factory.

“I was offered a position of the deputy head of production. My candidacy had to be approved in the partkom. I wasn’t a party member. I came to the office room, closed the door, and started thinking, ‘What is the party like, if there is a priority?’ And then I decided that I would be an ordinary engineer, but I would not enter the party. I said the same to the head. And he replied to me, ‘Kalnysh, I have 1,200 communists in the partkom, and I just need one deputy head of the production.’”

Kalnysh received two medals for his work. He says that there should be five of them, but he didn’t get the rest since he was not a party member. However, Semen Kalnysh assumes that he has no regrets about it.

“There was an order to make these people suffer and die. That’s it“

Replying to the question, who is guilty that his childhood memories forever darkened with the Holodomor, Semen Kalnysh says that back then he couldn’t tell it for certain, but now he thinks that Moscow had an influence and impact. Since there were famines in the Kuban, in the Urals, and in Ukraine.

“Of the Holodomor as genocide I think in these terms: if there was an order for this Vaniushka to go searching with shchup, it means that it was an intentional purpose to export somewhere this food, the grain. There was a decision to make these people suffer and make them die. That’s it.”

Semen Kalnysh hopes that there would be more discussions on the Holodomor in the future, and he thinks that the history of our country deserves to be known and remembered.

“I think that whatever the history is, whether it’s a history of the tsar regime, or the Soviet Union, or independent Ukraine, it’s history. Whether it was positive or negative, people lived in it! And the history should remain for the next generations. This is my position.”

We should know the history of our nation to avoid repeating similar crimes of genocide ever again.

In fact, the story of Semen Kalnysh has already become a part of the untold till the present-day history of our country thanks to the “Holodomor: Mosaics of History; Unknown Pages” project of the Holodomor Museum, supported by the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

Further reading:

- Surviving in the “collective farm paradise”: voices of living Holodomor witnesses

- How my father saved his co-villagers from starvation during the Holodomor

- “Let me take the wife too, when I reach the cemetery she will be dead.” Stories of Holodomor survivors

- Stalin’s management of Red Army proves Holodomor a Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

- Holodomor, Genocide & Russia: the great Ukrainian challenge

- Bread from tree bark and straw: students launch online “restaurant” with Holodomor “recipes”

- Ukrainian Holodomor Museum launches crowdfunding campaign to create main exhibition

- So how many Ukrainians died in the Holodomor?

- Holodomor in Kharkiv through the lens of Austrian engineer: photo gallery

- Holodomor survivor stories come to life in mobile app for tourists

- Holodomor: Stalin’s punishment for 5,000 peasant revolts

- Was Holodomor a genocide? Examining the arguments