Since gaining its independence in 1991, Ukraine keeps trying to revive the Ukrainian language in all areas of life after centuries of Russification.

Prior to 1918, most of Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire which had only one official language — Russian — that remained the language of prestige while Ukrainian, the second most-spoken language in the entire empire, was oppressed and marginalized.

The Soviet Union, a successor to the Russian Empire, pursued the policy of creating the so-called “Soviet people,” a non-national communist entity that happened to be primarily Russian-speaking. The USSR saw enemies not just in class opposition of any kind, but also in national activists in the vanquished nations, which led to mass terror on Ukrainians, especially throughout the early Soviet history, when the “de-kulakization,” Executed Rennaisance, Holodomors, deportations, years of imprisonment in GULAG concentration camps destroyed in uncounted numbers the most active, independent, or just recalcitrant Ukrainians who found themselves under Soviet rule.

Formally, the Ukrainian language was the principal local language in the Ukrainian SSR, however, in practice Russian dominated in all areas of life as the Soviet Union’s state language and “language of the inter-nation communication.”

Nowadays, Ukraine’s every step aimed at widening the use of the Ukrainian language in Ukraine and developing the language competence among Ukrainians comes under harsh critique by the local pro-Russian politicians and the Russian Federation, who usually label any improvements with Ukrainian as violating the rights of local Russian-speakers, most of which, however, still identify themselves as Ukrainians by nationality.

Belarus

Following the collapse of the USSR and restoration of the sovereignty of the countries annexed by the Soviets in 1918-1939, Belarus and Ukraine had an analogous situation with national languages, as Russification policies of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union not only promoted Russian as the empire’s language of prestige but also mostly displaced the national languages in education and the public sphere.

Both Belarusian and Ukrainian languages are the closest relatives to Russian – the three share a lot of distinctive features, making up the Eastern Slavic subgroup of the Indo-European family’s Slavic group of languages. The Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Russian languages are pretty much mutually intelligible — at least, Belarusian and Ukrainian speakers have little difficulty understanding Russian and each others’ language. Native Russians can understand both Ukrainian and Belarusian, albeit to a much lesser extent.

The mutual intelligibility contributed to the effectiveness of the impact of the long-standing Russification policies among the Belarusian and Ukrainian populations as it made the transition to Russian much easier for the East Slavs than, say, for Georgians or Uzbeks.

According to the only Russian Imperial Census of 1897, conveniently visualized on this interactive map, the number of those who used Belarusian as their primary language in the empire’s five predominantly Belarusian-speaking governorates was over 5 million or about 68%, with Belarusian-speaking minorities totaling 280,000 in adjacent Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian governorates.

In the late Soviet census of 1989, about 66% of Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic’s citizens (BSSR) called Belarusian their mother tongue. By the 1999 Belarusian census, the percentage of Belarusian speakers was higher by about 8% than 10 years before, and then it plummeted by 20% in the next 10 years down to 53%, according to the census of 2009. Moreover, despite the fact that the majority of Belarusians still call Belarusian their mother tongue, the Russian language dominates as a spoken language, especially in cities.

The original sources don’t include the absolute numbers and percentages shown in the table, therefore we had to calculate percentages based on the sum of the fields “called their nationality’s language as their mother tongue” for Belarusians and the figures showing how many people of other nationalities called Belarusian their mother tongue.

These figures mirror the changes in Belarus’ language policies and the results of those over the last 30 years.

In early 1990, the year preceding the collapse of the USSR, the BSSR Supreme Soviet adopted a law On Languages in the BSSR aimed at increasing prestige and use of the Belarusian language over the upcoming 10 years. The government-sanctioned a relevant state program later the same year.

In the first years of Belarusian independence, the post-Soviet government promoted the Belarusian language and encouraged its wider usage in educational institutions, on TV and radio.

In 1992, 55% of first-graders were going to be taught in Belarusian and the then deputy minister of education predicted that the entire system of education would shift to the Belarusian language in 10 years.

- Read also: Russian as a minority language in Ukraine vs Russian as Putin’s weapon: Is there a compromise?

In March 1994, months before the country’s current dictator Aliaksandr Lukashenka came to power, Belarus adopted its constitution that declared Belarusian to be the sole official language with the status of the “language of inter-ethnic communication” given to Russian.

In May 1995, about a year into the reign of former Soviet collective farm director Lukashenka, a referendum was planned that initially intended to pose one question — about economic integration with Russia. However, Lukashenka interfered and added three other issues to the upcoming voting, proposing to replace the country’s historic flag and coat of arms with the Soviet-times one sans Soviet symbols, to equalize the status of the Russian language with Belarusian, and to extend the presidential powers allowing him to disband the parliament.

All four initiatives were reportedly approved by a landslide (79-87% of votes).

In the wake of the controversial referendum, state support for the Belarusian language and culture dwindled and Russian restored its Soviet-style dominant position in the country. For now, Belarusian is considered “vulnerable” by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

How similar and different was it to Ukraine?

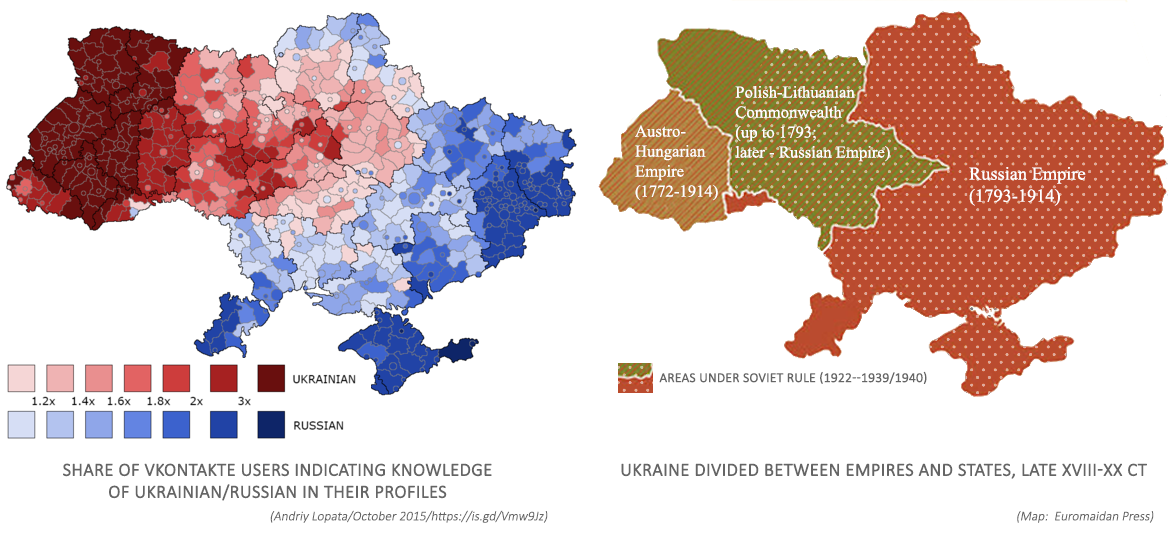

The initial Belarusian language situation in the 1990s was close to Ukraine’s, however, Belarusian was in even more substantial decline. The entire territory of Belarus was part of the Russian/Soviet empire for centuries. The limited exceptions were a short-lived nation-state in 1918-1919 and the west of Belarus being part of Poland in 1922-1939.

Meanwhile, several west-Ukrainian regions were part of the Austro-Hungarian empire for centuries and, following its demise after WWI, were incorporated into Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania.

In these territories, even though the Ukrainian language and culture were evicted from education and public life, the Ukrainian population preserved their national identity and suffered less de-Ukrainization than central, southern, and eastern regions of Ukraine, which were Russified for several centuries straight just like entire Belarus.

In the Russian Empire, both Belarusian and Ukrainian were often considered the rural spoken dialects of Russian.

In the late Russian Empire, the Russian language prevailed in most of the cities of both Belarus and Ukraine. For example, the Census of 1897 showed that 80% of inhabitants of Ukrainian rural regions called Ukrainian their native language, while in cities there were only 32.5% of Ukrainian-speakers on average, or even less.

With the industrialization and urbanization of the early and mid-20th century, urban populations were growing faster than the number of national language speakers in the cities. Settlers from the whole empire arrived in newly created industrial centers, using Russian as a lingua franca. This eventually led to the almost total Russification of major cities under the late Russian Empire and further under the Soviet Union.

Ukraine avoided the same scenario in 1999 when a local communist leader, Petro Symonenko, who challenged then-incumbent Leonid Kuchma, reached the run-off at the presidential elections yet lost by some 20%.

As the statistics show, the Belarusian language has been losing its ground to Russian, and with the country’s aspirations to further integrate with Russia, the Belarusian language risks ending up on the brink of survival.

Now, Ukraine’s ongoing efforts at reviving the Ukrainian language in the country face the opposition of the same kind as in middle-1990s Belarus. Then, local pro-Russian politicians, backed by Russian officials, advocated for the Belarusians’ right to not know the national language. As in Ukraine, this was disguised as a struggle for the rights of Russian speakers.

Ireland

The Irish or Gaelic language is one of the Celtic languages, a group within the Indo-European languages that was once prevalent not just in the British Isles, but across entire Europe, covering in the 3 BC most of the territories of modern Spain and France, and stretching from the Atlantic up to the Black sea. However, the centuries of Roman and Germanic conquests reduced the areas where the Celtic languages were spoken to parts of British islands and France’s Brittany.

Starting from the 12th century, primarily Gaelic-speaking Ireland was the first English colony to later become Great Britain’s client state in the mid-16th century and then part of the United Kingdom in 1801. It gained independence in 1922, seceding from the United Kingdom, although without Northern Ireland that remains in the UK till this day.

Under British rule, the Irish language lacked an official status and was actively discouraged and suppressed so that by 1800, “Irish had ceased to be the language of anyone in Ireland who had political, social or economic power.”

Nevertheless, it is believed that the number of Irish speakers at the time still was four million people or even higher. Yet, on the one hand, they were mainly the poor, who comprised most of the population. On the other hand, the language had retreated completely from the country’s east.

Closer to the middle of the 19th century, Ireland experienced a language shift that resulted in English becoming the main language on the island. The growing market economy and increased centralization of government contributed to viewing English as the language of prestige. Irish was further marginalized and associated with poverty.

The Great Hunger of 1845-1852 drastically decreased the population of Ireland by 20-25% as about 1 million people died and more than a million emigrated and the emigration continued in the subsequent years. In 2016, the combined population of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland was about 6.66 million which still remains lower than than the pre-famine population of 8.18 million in 1841.

Irish was totally omitted from the curriculum of public schools until 1878, when it was added to be learned after English, Latin, Greek, and French. In 1928, independent Ireland made Irish a compulsory subject at schools, yet in the following decades, support for the language was gradually reduced.

Attempts to revive Irish in Ireland continue to this day.

The Irish language is the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland under the Constitution of Ireland, and English is the other official language. Despite the government’s various measures for strengthening the language in all areas, such as the 20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010-2030, Irish is still considered “definitely endangered” by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, and English remains dominant in the country.

At the 2016 census in the Republic of Ireland, the total number of people who said they could speak Irish was 1,76 million or about 40% of the population of about 5 million. However, only 6.3% claim to speak it weekly, and only 1.7% speak it daily outside the education system. And only some 8,000 of the 2016 census forms were completed in Irish.

Similarities with Ukraine

The histories of Irish and Ukrainian are similar not only because of centuries-long oppression. Ukraine, like Ireland, also saw a great famine — the Holodomor — that also hit primarily poor rural populations who were carriers of the national language.

Another parallel is reducing the status of the national language to an unpopular rural tongue while promoting the ecdemic language among local elites. This resulted in a significant part (or even vast majority) of the population acquiring the language of prestige.

As a result of the long-standing colonization process, it is next to impossible to find a Ukrainian who can’t speak Russian, even if Russian is their second language. The same applies to the speakers of Irish in Ireland and their knowledge of English.

The Czech Republic

Czech, closely related to Slovak, is a West-Slavic language together with Polish and two native Slavic languages of Germany, Upper and Lower Sorbian.

As of 2012, the Czech language was spoken by 98% or about 10 million residents of the Czech republic. However, the current language situation in Czechia hasn’t always been this bright.

“Czech culture blossomed under the 14th-century emperor, Charles IV, but faced turbulent times with the Hussite wars that came soon afterwards. With the onset of rule by the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, Czech went into decline as a written language, with German becoming the language of the elite. Czech remained the language of the countryside,”

Since the early 17th century, Habsburg monarchs had actively Germanized the Czech lands. The Czech language was mostly eradicated from education, state administration, and among the upper classes.

Czech was reduced to a means of communication between often illiterate peasants.

In response to such policies, the movement of the Czech National Revival took place in the 18-19th centuries. It aimed at reviving the language and national identity.

In the 19th century, Czech grammars and a dictionary were compiled. They modernized the language, making it possible not just for literature, but for original Czech research to develop.

The National Theater and National Museum were established and the Czech-language journal of the Bohemian Museum provided a platform for the national intelligentsia to share their ideas in their own language. The revival movement succeeded and the Czech language was restored as an official language.

As of 1910, Czech was spoken by 63.2% in Bohemia (German by 36.8%) and by 71.8% in another Czech region, Moravia (with 27.6% primarily German speakers).

Parallels with Ukraine

In the 19th century, Ukraine saw a similar movement aimed at the revival of the Ukrainian language and culture. However, unlike quite liberal Austro-Hungary, the Russian Empire met it with hostility and boosted its crackdown on the Ukrainian language, prohibiting works of Ukrainian authors, banning the Ukrainian language even in primary school, church, theater.

The Czech case shows that revival of the national language is possible given the right measures, conditions, attitudes in the society.

Further reading:

- Post-Euromaidan gains for Ukrainian language challenged by creeping Russification and state indifference

- Should Ukraine take over the Russian language? Scrutinizing Prof. Snyder’s arguments

- Services in Ukrainian by default: new phase of language law sparks debate

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language: Infographic

- Russian as a minority language in Ukraine vs Russian as Putin’s weapon: Is there a compromise?

- The Ukrainian language is gaining ground, official says (2018)

- Why Ukraine’s language law is more relevant than ever

- Ukraine creates free online courses of Ukrainian language for foreigners

- Ukraine adopts law expanding scope of Ukrainian language (2019)

- The rebirth of Ukrainian literature and publishing: famous contemporary authors and new policy for their support

- Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas