25 October 2020 is the day when local elections will take place across Ukraine. Citizens will choose the heads of villages, towns, and cities, as well as the heads of the corresponding councils. For the first time, the elections will take place according to the new Election Code.

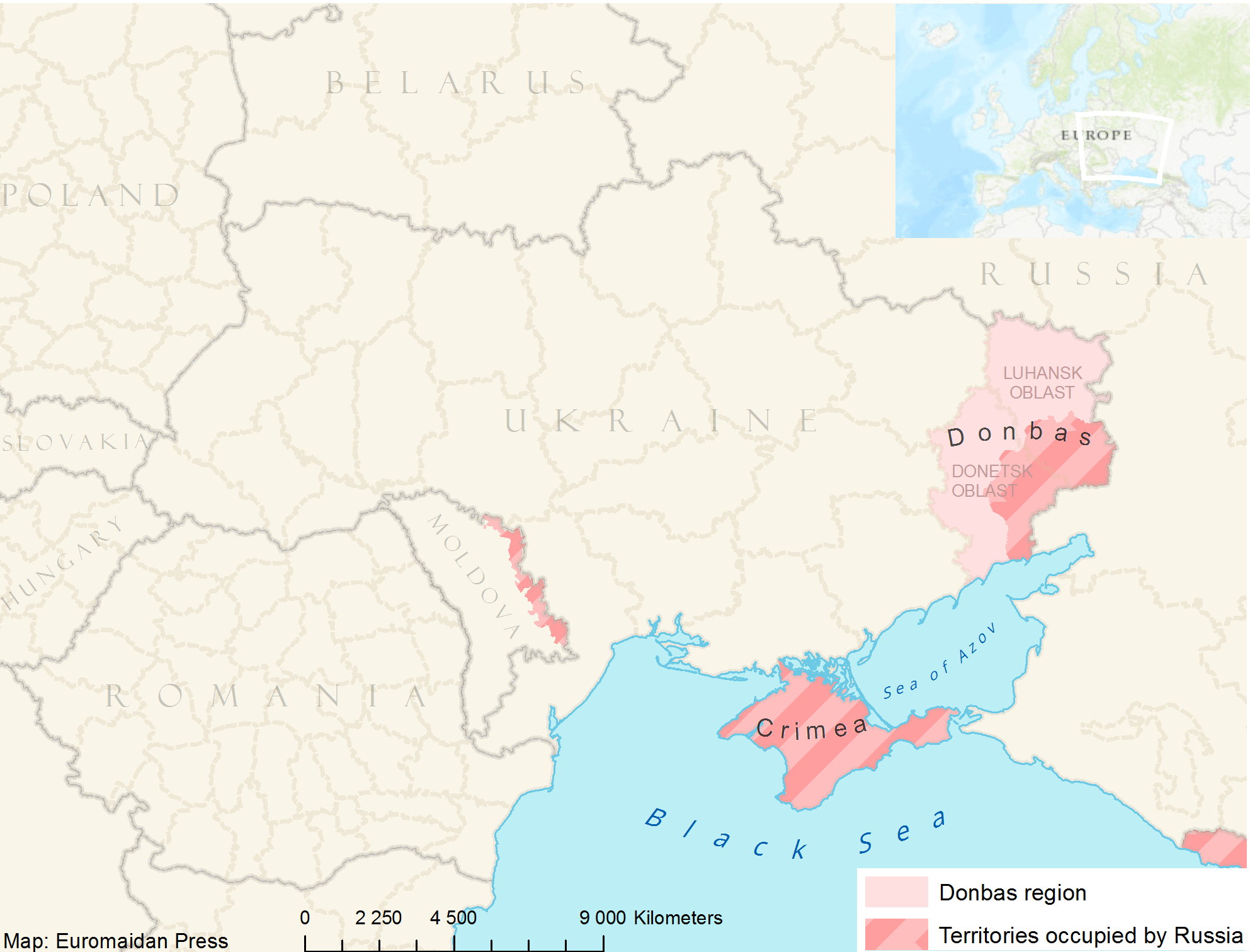

Since the de-facto war in Donbas started in 2014, Ukraine’s political scene has changed greatly. New political parties have appeared. Some of them gained seats in Parliament. New officials were appointed to executive bodies.

However, the old so-called political elites of the ancien regime have not left the stage. Even more, those whose politics or direct actions led to the war appear to regain power or at least strengthen their hold.

Donbas, the easternmost region of Ukraine, has not yet managed to diffuse the influence of these people.

As Ukraine nears its local elections, Euromaidan Press talked to Kostyantyn Reutskyi, executive director of the human rights organization Vostok-SOS which supports citizens of eastern Ukraine.

Last year, Reutskyi, together with two of his colleagues, ran in the 2019 parliamentary election. None of them won. However, they learned a lot about why local citizens tend to vote for a particular candidate.

On 9 September, the Sociological Group Rating released its research on Ukrainians’ electoral preferences. According to the Rating’s poll, leading in the parliamentary race across Ukraine is President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Servant of the People party (25.7%); pro-Russian Opposition Platform for Life is second (16.7%); Petro Poroshenko’s European Solidarity third (15.6%); Yuliya Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna fourth (9.4%); and Oleh Liashko’s Radical Party fifth (6%).

The poll does not provide data by region. However, the thinking is that the pro-Russian Opposition Platform for Life, as well as pro-Russian mayoral candidates, will win majorities in eastern Ukraine.

In 2019, among the main goals Reutskyi and his colleagues set for themselves when campaigning was:

- to inspire local citizens to enter politics themselves;

- to draw attention to the problem that unpunished representatives of the ancien regime are regaining power.

“These people were involved in separatism and betraying Ukraine’s interests in 2014. They had been under investigation and managed to avoid responsibility. And nowadays they run for positions in power, probably to provide the same policy they did before.”

The key message of Reutskyi and his team was “Let’s get involved in politics, otherwise scoundrels will.”

To give a sense of what kind of local candidates are campaigning now in Donbas, this is a brief overview of some of the “old elites” of politics in the region.

Controversial politicians of Donbas represented by ancien regime corrupts and supporters of Russian invasion

Reutskyi and his colleagues point to the shortsightedness of local citizens who usually ignore the past actions of politicians.

Reutsky describes Volodymyr Struk, his main opponent in last year’s parliamentary election:

“He is an ex-MP, and before it, the perennial mayor of one of Luhansk satellite cities, representative of the Party of Regions [of runaway president Viktor Yanukovych], and an associate of the ‘powerbroker’ of Luhansk Oblast Oleksandr Efremov. At the time of the Euromaidan Revolution, Struk organized thugs to attack the protests in Luhansk and Kyiv. During the so-called Russian Spring, he financed the creation of the so-called self-defence squads and armed them. Now he has moved to the north of Luhansk Oblast, trying to take hold there.”

Reutskyi stresses that last year Struk — who was among those who kindled the war in Luhansk Oblast — ironically campaigned under the promise of bringing peace to the region. However, he did not win a seat in Parliament. Expectations are that this time he will run for mayor of one of Luhansk Oblast cities, with a high chance of victory.

One of the key figures in the region is Serhiy Shakhov. It was Shakhov’s associate who won a parliamentary seat in the same district where Reutskyi and Struk campaigned. Shakhov is another example of the old guard local elites. For some time after the Euromaidan Revolution, Ukrainian media reported on his strong ties to the Yanukovych family, as well as his shadowy corruption schemes on behalf of the family. However, due to his intelligent media campaigns, Shakhov managed to publicly distance himself from his old connections.

Notwithstanding, Shakhov was well known for his own large-scale scheme to bribe voters.

Last year, he ran as an independent candidate and now is a member of Parliament’s Trust [Dovira] sector. A number of his associates are also running for key positions in Luhansk Oblast.

“I see a great threat in Shakhov’s strengthening. Now, he takes his people to a number of Luhansk united territorial communities and sees his gaining control over the resources of the oblast as his goal,” says Reutskyi.

If political leaders do not recognize the threat Shakhov will possess over time, Reutskyi believes he could become another corrupt powerbroker of the oblast — like Efremov.

“To me it is sad to observe how some democratic politicians and civil society activists who promote democratic transformations enter into situational alliances with Shakhov.”

Nellia Shtepa, ex-mayor of Sloviansk – the first city to fall under Russian aggression in 2014 (liberated later that year) — is another controversial Donbas figure whose chances of returning to power are high.

German NGO strengthens civil society in Sloviansk, first victim of “Russian Spring”

In 2014, Shtepa was detained and accused of encroaching on the territorial integrity of Ukraine which led to several deaths and the creation of a terrorist group.

The pro-Russian terrorist group led by Russian FSB officer Igor Girkin seized the city of Sloviansk in April 2014, and then-Mayor Shtepa threw her support behind the militants. During the six years of court hearings against Shtepa, judges were replaced, and courts were frequently disrupted. In 2017, she was released and put under house arrest. In early 2020, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that Ukraine pay EURO 3,600 compensation to Shtepa after considering her complaint against her long-term detention which did not allow for alternative preventive measures, such as an electronic monitoring ankle bracelet.

In the upcoming elections, she is campaigning for Mayor of Sloviansk again.

The old political elite of Donbas, whose core was the Yanukovych family, and which in 2014 were associated with the pro-Russian movement, is still popular in the region. Paradoxically, those who were blamed for opening the doors to war now campaign under the slogans of bringing peace.

Donbas citizens vote for the return of the status quo, not for Russia

Reutskyi suggests that the citizens of Donbas do not recognize the threat of Russia, nor — just as menacing — of pro-Russian politicians, because of their own psychological damage as victims of war.

“People tend to displace the main reason for the problem as it might be very traumatic for a person to comprehend it.”

Reutskyi points out that the main messages for pro-Russian politicians are that everything will return to normal.

“In fact, people do not that much have pro-Russian feelings, they rather want a calm life like it was before the war. They want to return to the status quo. That is exactly why many believe the Opposition Platform For Life [the main pro-Russian political force mostly made out of ex-Yanukovych politicians].”

Reutskyi describes last year’s parliamentary election campaign as a festival of ways to bribe voters.

The abovementioned Shakhov was seen giving out sugar to the elderly. A candidate in the city of Lysychansk had roads re-paved — they had deteriorated in less than a year because of cheap construction. Still, because there had been no road repairs for many long years, people saw this as a great contribution to their locale. Shakhov even handed out glasses to old people. A common practice among candidates is to give food packages and even money to voters.

An observation by Reutskyi and his colleagues is that Donbas locals tend to focus on their day-to-day problems, not taking a long-term perspective. They ask candidates for simple things: “Will you repair the road?” If a candidate answers yes, the voters will naively support them.

Such candidates manipulate people long before the elections.They bribe local opinion leaders to create a positive image for them year-after-year.

Yet, if all candidates use bribing tactics, why do some in particular consistently win? Reutskyi explains Shakhov’s success in the region:

“He is good at playing the role of a person who cares about voters and sincerely wants to help them. He also has some key representatives among the locals whom he pays money to campaign for him permanently, during the entire period between the elections. His close representatives, as well as he personally, come to different locations. To be honest, he indeed comes to voters and gives them attention. He listens to them and promises that he’ll make their life better. People see that he is one of only a few who comes and talks to them. People need attention. And apart from these meetings, there is a physical manifestation of this attention in the form of a few kilograms of sugar.”

Reutskyi underscores Shakhov’s strategic media campaign. For example, recently the MP announced Struk was running for the mayor of Ukraine’s capital Kyiv.

“Probably he did it not to win, but to ease the task for his associates to hold positions in Luhansk united territorial communities. The mechanism is simple. People vote for strength. In such a case if he runs for the mayor of Kyiv he is perceived as strong.”

No matter what the real intentions of candidates, longtime attention to the citizens of Donbas — the region most abandoned by the democratic forces — is the key to win votes. Equally so are the promises — even when empty — to bring peace.

Democratic forces do not devote much effort to the region

Reutskyi admits that pro-democratic forces do not conduct a significant level of activity in eastern Ukraine.

“Unfortunately, eastern Ukraine is seen as an area of ex-representatives of the Party of Regions. And all the Ukrainian political parties don’t try to take hold there to change the political situation. The only exception is Batkivshchyna [Yuliya Tymoshenko’s party] which, however, also doesn’t intend to increase its number of supporters in Donbas.”

He admits that most democratic segments of government resort to making agreements with ex-Party of Regions representatives for some form of parity. Or they give up the region to them in exchange for loyalty on the national level.

“This improper tactic leads us to the increase of the pro-Russian attitudes imposed by the old eastern elites. And it all leads to the increase of the pro-Russian attitudes in Central Ukraine as well.”

Reutskyi concludes that the systemic work of the democratic forces and the government in the region is the only chance to improve the situation there.

Breaking the monopoly of politicians of ancien regime can ease the development of Donbas

Reutskyi suggests the following tactics to improve the political situation in eastern Ukraine:

- Destroying the monopoly of the ex-Party of Regions by completing all investigations of its representatives; the worst examples being those cases relating to financing terrorism or committing treason;

- Expel officials still loyal to the old elites.

Lustration preventing comeback of Ukraine’s ancien regime challenged after five years

Reutskyi also sees educating society and the support of local activists as important drivers for democratic change in the region.

Youth initiative breathes life into Donbas’ first occupied city| Video

Locals disapprove of the situation in their region and are twice more Euroskeptic than national average

In April 2020, the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation released a poll it conducted with the Center for Political Sociology. The study analyzed the attitudes of people living in the government-controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

In particular, it showed that locals mostly disapprove of the situation in the region. 54% of the respondents of Donetsk Oblast saw the situation as tense, and 12% as explosive. In Luhansk Oblast, the discontent was even higher — 63% tense and 13% explosive.

The research showed that residents of Donetsk Oblast were much more likely to recognize Russia’s involvement in the war.

When asked whether Ukraine and Russia were at war, the oblasts differed again. 64% of Donetsk respondents agreed, while only 20% disagreed. In Luhansk, 38% agreed, while 43% did not.

However, since 2018, recognition of Russia’s involvement in the war has increased in both oblasts.

Regarding the actual form of Russia’s involvement in the conflict, in Donetsk Oblast, the most popular response (46%) was that Russia totally controls the so-called “LNR/DNR.” In Luhansk Oblast, only 20% saw total control. When it comes to humanitarian aid, 40% of respondents from Donetsk Oblast, while 44% from Luhansk, are confident that Russia provides humanitarian aid to Donbas. Compared to the similar report of 2018, the perception of Russia’s actions has become more positive.

In eastern Ukraine, 26% were ready to vote to enter the EU; 50% were against, and 5% were undecided. Opposition to NATO was even stronger: 16% of the respondents were ready to vote for it, 62% would vote against, and 22% were undecided.

Whereas in all of Ukraine, 56% would vote for entering the EU and 43% for NATO, 26% and 31% against, and 22% and 25% were undecided.

Reutskyi notes some positive changes since 2014: the government, which up to 2014 was quite monolithic and closed, now has the highest level of openness since Ukraine’s independence in 1991.

Future of war resolution depends on government-controlled Donbas

Discussions on the future of Donbas usually concern the future of its occupied areas and the ongoing military conflict. Meanwhile, the other parts of the region, those that are controlled by the Ukrainian government, are usually ignored by the national government and by politicians in general.

Yet, it is these free areas of Donbas that will play the lead role in the reintegration of the entire region when freedom returns.

Local elections are the time when Donbas chooses the vector of its development for the next several years. Without building democracy and a democratic mindset, in a free Donbas, the psychological return of the occupied territories is hardly possible.