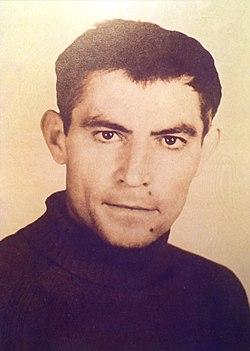

Particularly illustrative is the story of a Ukrainian politician, people’s deputy, and oligarch, former KGB agent Victor Medvedchuk (65) who “defended” the renowned Ukrainian poet, Vasyl Stus (1938-1985) as his attorney in a 1980 court hearing. In truth, Medvedchuk did not defend Stus at all, instead, he declared his ostensible “guilt” and thus contributed to Stus’s incarceration. The poet died five years later in a correctional labor colony — his only crime had been voicing, in his works and in public, the cynicism of the Soviet System and Ukraine’s relentless quest for freedom.

Medvedchuk played the same role in the imprisonment of other Ukrainian intellectuals. Yet, his current status demonstrates how Ukraine has not attained full political independence. UPDATE (2021): Medvedchuk was arrested in Ukraine in 2021 thus bringing justice to the case of Vasyl Stus.

The story of Vasyl Stus finally gained popularity in Ukraine, when film and books on his life appeared

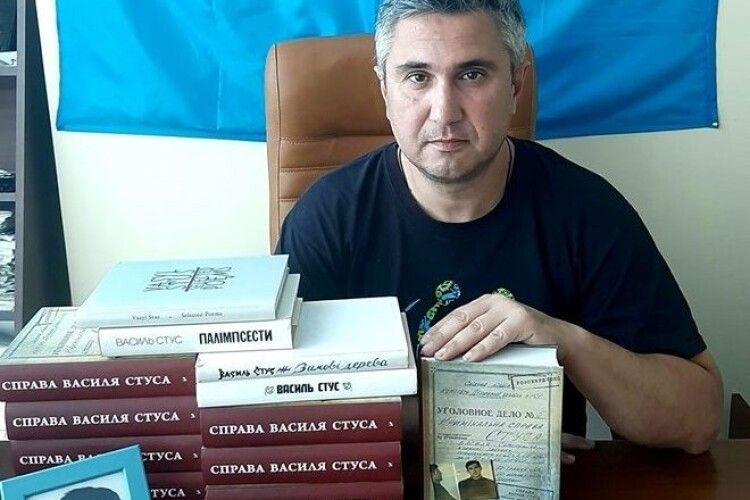

Although much delayed, the story of Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus finally gained its proper due, when the biographical novel Заборонений (Prohibited, 2019) and the film of the same name were released this year. Just as importantly, historian and journalist Vakhtang Kipiani recently published his research and archival documents regarding Stus’s conviction in Справа Василя Стуса (The Case of Vasyl Stus).

Video about the film: [embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNnZtKiDfBY[/embedyt]

Although Stus’s story has become iconic, it is not unlike other stories of the Ukrainian dissident movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

During the political Thaw — a lessening of constraints and partial liberalization — under Nikita Khrushchev from the early fifties to the early sixties, Stus continued his studies as a doctoral aspirant (Ph.D. candidate) in Literary Theory in Kyiv. This was when he published his translations of Rilke and Goethe, the first collection of his verses.

Yet, in 1964, a new wave of arrests began as Leonid Brezhnev took over the communist party. Stus supported Ukrainian dissidents Ivan Dziuba and Viacheslav Chornovil who publicly condemned new arrests of the Ukrainian cultural elite. They did so most poignantly during the 1964 premiere of Serhiy Paradzhanov’s internationally acclaimed film about ancestral Ukrainian highlanders in the Carpathians, Тіні забутих предків (Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors).

Stus called upon those in the audience who opposed totalitarianism to stand. For that he was expelled from university, and the KGB began constant surveillance of his every move.

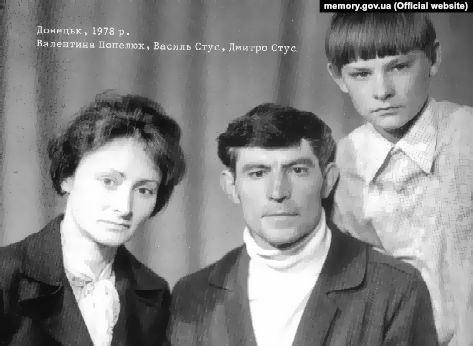

In 1972, Vasyl Stus was convicted of “the dissemination of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” and sentenced to five years of imprisonment and three years of deportation to Siberia. During a few months of freedom — if it may be called so — in 1979-1980, he became a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group advocating for human rights in Soviet Ukraine. Then in 1980, Stus was convicted for the second time – 10 years in prison, plus five of deportation. He died in 1985 in his prison сell under questionable circumstances.

During this second trial, Medvedchuk acted as his “defense attorney.” Shamefully, Medvedchuk not only failed to defend Stus for a false conviction, he went so far as to denounce his client and proclaim his “guilt” — an act completely contrary to his sworn legal code of ethics, which should have compelled him to deliver a rigorous defense.

The path taken by Stus demonstrates the gradual disillusionment in the Soviet system of many dissidents. At first, he was not a radical opponent of the regime and promoted Ukrainian culture within the allowable limits.

However, once new waves of arrests started in the mid-sixties, he went on the offensive. From 1965-1972, Stus wrote open letters to the Writers’ Union, the Central Committee of the Communist Party, the Verkhovna Rada of Soviet Ukraine, and others. He criticized the ruling system, which in the aftermath of the Thaw returned to its former dogmatism: totalitarian control, cult of personality, and an even harsher disregard of human rights. Stus soon learned that an attempt at dialog was naïve and futile.

During his first trial, he had still tried to defend himself, reserving some hope for justice. He testified that he was not against the Soviet system and was only trying to improve inconsistencies. In his closing submission, he even admitted that some of his earlier expressions were too radical. His closing comprised a dozen pages in the official protocol of court hearings. It was his last attempt at any sort of dialogue within the system.

As transcripts from the late 1970s and at the 1980 trial reveal, the only answers Stus gave to questions were, “I refuse to answer,” “I will not comment on this,” and “I reject any Soviet attorney and will accept only an international one.” At this stage of his life, following his unjust convictions, he had no hope left for any positive changes within the Soviet system.

The ultimate goal of Soviet repressions was to coerce those who opposed it either into acceptance or submission. With Stus however, the opposite occurred – he rejected it entirely. In 1979, he wrote a statement to the Soviet authorities in which he disclaimed his Soviet citizenship:

“To hold Soviet citizenship is an impossible thing for me. Being a Soviet citizen means being a slave.”

In 1979, he became a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, but at the same time heavily criticized it. Stus felt that group members were still too loyal to the regime and too naive to think they could make a difference by working within the system. He pointed to the Polish Solidarity movement as an example of a society which, in 1980, was already holding mass strikes. Although he expressed his ambivalence to the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, he joined it:

“[Upon my returning to Kyiv in 1979] I saw that people close to the Helsinki Group are being brutally repressed. So, at least, were Ovsiyenko, Horbal, Lytvyn — and then they dealt with Chornovil and Rozumnyi. I didn’t want that kind of Kyiv. Seeing that they had actually left on their own, I joined [the Ukrainian Helsinki Group] because I simply could not have done otherwise. When life is taken away – I don’t need crumbs.”

In 1985, Ukrainian intellectuals in the diaspora nominated Vasyl Stus for the Nobel Prize. They started the arduous task of preparing his many works, advocating for him vociferously. Sadly, he died that same year. His health had been deteriorating, especially after his starvation campaign. His death was suspicious — whether he died from illness and exhaustion, or whether he was killed remains unknown.

Soviet courts vs Kafka’s The Trial: which is worse and whether a lawyer could do anything in the Soviet system

Stus’s court case is a telling example of the total subjugation of the Soviet system. As in Kafka’s novel The Trial, in the Soviet system, as soon as KGB officials detained an individual, all hope was lost. It is difficult to say which is worse – to be arrested by two unidentified agents for an unspecified crime, as in The Trial, or to find your reality suddenly turned upside down and yourself deemed mad in a court judgment.

The irony of the Soviet system is that all court procedures, all transcripts of both the convicted and the accusers, and all judgments and sentencing were meticulously documented. By the same token, however, the thorough practice provides the perfect methodology to decrypt the text and reveal the truth of events.

When studying Soviet court documents, one should simply reverse all that appears — changing yes to no, minus to plus, up to down, negative accusations to positive assertions, and so on. By this bizarre interpretation, it is possible to see what actually happened.

The following are fragments from the 1972 Court judgment against Stus:

“These libelous documents denigrate the socialist attainments in our country; a vicious slander has been directed against the Soviet democracy and guaranteed by the constitutional immunity of a person, against the national policy of our country; attempts have been made to “prove” the impossibility of building a communist society in the Soviet Union.

…

This [a letter of Stus] libelous document, when it was attained by the publishers of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists abroad, was widely used in propaganda activities against the Soviet Union.

…

In these verses, the slander is directed against the work and life in the collective farms, the Soviet democracy, the Soviet people.

…

In these verses, an attempt is made to prove to the reader a perverted view of the Soviet socialist society.

…

In the article “The Phenomenon of the Epoch” … tried to impose on the reader anti-Soviet, nationalist views and ideas about the evaluation of the creativity of the Soviet Ukrainian poet … tried to prove the “harmfulness” of the principle of partisanship in literature. At the same time, he tried to impose distorted hostile views on the collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union.”

No less illustrative were the protocols of official searches. Any documents that were found, if considered useful for the case, were marked, “Document of ideologically harmful content,” “Slanderous document,” or with the label “In general, the records are ideologically harmful by their content.”

Other extracts worth examining are the reviews of Stus’s poetry, written by Arsen Kaspruk, a scholar of the Kyiv Institute of Literature, as had been commissioned by the KGB. On the collection of verses titled Winter trees Kaspruk writes:

“Soviet life appears here as voluntary custody where people live and act: slovenly ethics teacher, yesterday’s Christ-seller, drunkard, gigolo… More disgusting, more horrible hatred could not invent the most ingenious prejudice against our reality … It is not necessary to prove that Stus’s book is harmful in all its ideological directions, in all of its essence. A normal unprejudiced person can read it only with abhorrence, with disdain for the ‘poet,’ who so defames his land and his people.”

A reviewer also wrote about the collection Cheerful Cemetery:

“The Soviet people, according to Stus, are soulless vending machines, people without heads, mannequins that mechanically play a silly performance set by the scheme.” “From the literary side, Stus’s verses are something stupid, malicious mutter, and from the political is a conscious slander, denigration of our reality.”

An attorney who was appointed as a defense for Stus, also proved to be the exact opposite of a defender — as Stus put it, in effect, he was a second prosecutor. In the 1980 court hearings, Medvedchuk made no attempt to soften Stus’s accusations. Nor did he inform relatives about the trial, which was his direct duty. Finally, he said at the end of the court hearing: “I consider the validity of Stus’s prosecution to be true.” Needless to say, for a defense attorney to agree with the prosecution, against one’s own client, is a travesty of ethics and a violation of his very role.

After his very first meeting with Medvedchuk, Stus knew that his defense would be a sham and wanted to reject the attorney, stating he would defend himself. His entreaty was summarily dismissed, under a supposed loophole in the regulations.

Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Ukrainian literary critic, and Svitlana Kyrychenko, a member of the Ukrainian human rights movement were fervent supporters, who publicly advocated for Stus. In testifying at the court, Kotsiubynska called Stus “a person with a pure conscience, unable to commit the slightest injustice.” Kyrychenko refused to make a statement to the court, saying she would only testify in a court where, “Stus himself will be charging, not sitting on the bench.”

Victor Medvedchuk as a collaborator with the Soviet regime and a KGB agent: facts about his role in the conviction of Vasyl Stus

Victor Medvedchuk was born in 1954 in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russian SFSR, where his father was exiled allegedly because of the cooperation with Nazis. In 1972, Medvedchuk started his studies at the law faculty of Kyiv State University. During his studies, he headed the Komsomol operational detachment of the voluntary people’s guard — a student organization that supported the regime and helped police target fellow students to harass and deter. In 1973, after having beaten a young so-called “offender,” Medvedchuk was relieved of all criminal responsibility — very likely because he became an agent of the KGB.

Upon completing his studies, Medvedchuk was invited into a group of “select lawyers” whose role was predetermined by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and KGB. They were entrusted with the most “important” cases and to “defend” the most “dangerous” opponents of the regime.

The roles Medvedchuk has played in Ukraine are worth examining. He has been a Member of the Coordination Committee on Combating Corruption and Organized Crime under the President of Ukraine (1994-99); Deputy Head of Ukrainian Parliament (1998-2001); Head of the Presidential Administration (2002-2005); People’s Deputy (1998-2006, and currently, 2019); as well as a Ukrainian oligarch and owner of several Ukrainian TV channels. Most telling is that Vladimir Putin is the godfather of his daughter. Medvedchuk vocally opposes the recognition that Russia committed aggression against Ukraine in 2014.

In a recent interview Medvedchuk explained his role in the conviction of Vasyl Stus as follows:

“…As Levko Lukyanenko once very rightly remarked when asked ‘Is [Stus] wrongfully convicted?’ he said, ‘Why? Legally condemned.’ They [dissidents] simply did not consider this power legitimate. And I, for example, considered the Soviet power legitimate.”

Medvedchuk also says:

“If anyone thinks that I could save Vasyl Stus, then he is either a liar or has never lived in the Soviet Union and does not know what it is. Such cases were decided not in court, but in party instances and the KGB. The court only formally approved the sentencing.”

Can such reasoning be an excuse for Medvedchuk? In a word, “No.”

Medvedchuk willingly became an agent of the KGB, and gladly accepted the offer to “defend” Stus, knowing exactly what that meant. Moreover, Medvedchuk’s pronouncements that the Soviet system and its laws were somehow legitimate, only underscores his adherence then to destroying Ukrainians who wanted to think independently from the Soviet Union.

To act as a defense attorney for someone who has been charged according to a special political article of the law, an attorney had to be a trusted person in the eyes of the Soviet system — a member of the ratified list.

In his book, Kipiani provides the testimony of Vasyl Ovsiyenko, a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, who was a political prisoner (1973-1977 and 1979-1988):

“In those years there was a list of attorneys, among whom you had to choose your lawyer if you were accused in a political case. These, of course, were verified people who had the so-called “admission” to our cases from the KGB … But there were exceptions. For example, Serhiy Makarovych Marysh had such an admission. He wrote a brilliant cassation case to protect Oleh Sergiyenko, arrested according to a political article of the law. After that, Marysh was thrown off the list immediately — he could only defend criminal offenders thereafter.”

Verified as a KGB agent, according to recent materials from the declassified KGB archives in Lithuania, Medvedchuk definitely was on the list. He “defended” not only Stus, but at least three other Ukrainian dissidents. In the case of Mykola Kuntsevych, when a prosecutor demanded a three-year conviction, Medvedchuk not only failed to oppose his sentence, but when so far as to ask the court to make it longer(!):

“I fully agree with the comrade prosecutor on the punishment. But, for reasons unclear to me, the prosecutor forgot that the accused had not yet served one year and nine months from the previous term. I think it is necessary to add this term to the new punishment.”

Medvedchuk apparently has not changed his views, even after 28 years of Ukrainian independence. In his interview with the BBC, he said that his perception of most Ukrainians is negative, adding that 46% of them have a negative attitude towards him:

“Well, that’s ok. I have a bad attitude towards them as well. How it could be different … 60% in Ukraine consider Russia to be an aggressor, and I don’t think so. Should I be among that 60%? No, I will be in the other part.”

The second argument against Medvedchuk is that even in the Soviet system — although there was almost no chance to save Stus — an ethical attorney would have tried to soften his conviction and actually support him at trial. Medvedchuk, however, was not only hostile to the Ukrainian dissident, but in complete violation of his professional responsibilities. This was underscored in the research conducted by Ukrainian lawyers Roman Tytykalo and Kostin Illia:

1. Medvedchuk did not even read the criminal case and did not file such a petition to do so. He did not file any protest or request, did not file any complaint, explanation, evidence, etc.

2. Medvedchuk did not support any petitions by Stus, including to provide him with the UN Declaration of Human Rights (Helsinki Accords), to consider the torturing in detention, and to be able to provide a final speech – all legal rights that were usually provided in Soviet courts.

3. When a provocateur who does not even know Stus spoke as a witness (normal Soviet practice), Medvedchuk was silent. However, he asked witness Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, who tried to defend Stus, about his anti-Soviet orientation.

4. Stus was rehabilitated in 1990 according to the same Soviet laws because “… he did not allow public calls for the violent overthrow, undermining or weakening of Soviet power. Stus fought for the establishment of democratic foundations in society, against certain violations committed during that period.” Medvedchuk could have tried to point out this legal Soviet norm to soften the conviction of Stus before he was convicted and died in prison.

5. Medvedchuk should not have proclaimed Stus as guilty in the court, according to the role of an attorney. Even according to Soviet law regarding the duties of an attorney, he had no right to do so. He, therefore, violated regulations.

The battle continues: In 2019, Medvedchuk sued historian Kipiani to prohibit publication of his book Справа Василя Стуса (The Case of Vasyl Stus)

Today, Victor Medvedchuk is one of the most influential Ukrainian oligarchs. He is the owner of pro-Russian 112 TV channel, a founder of the pro-Russian NGO “Ukrainian choice,” the people’s deputy for the pro-Russian Oppositional Platform, and an adherent of the disintegration of Ukraine.

At the end of August 2019, Viktor Medvedchuk filed a lawsuit claiming that Справа Василя Стуса (The Case of Vasyl Stus) should be banned because the information in it was allegedly false. The lawsuit was filed using these terms: “To protect the honor, dignity and business reputation of Viktor Medvedchuk.”

Commenting on the issue, Medvedchuk said that Kipiani’s book is allegedly an American provocation:

“This is a provocation. One of the steps that Americans are doing today. We have proof of this. They constantly provoke. This is from a series of things that are being done because Medvedchuk is taking a public position today, Medvedchuk is in public policy today, and Medvedchuk is an enemy to them … This is another provocation that, unfortunately, is taking place today. And we will survive it too. In the case of Stus, that was 38 years ago, I am glad that Americans have not found anything new in 38 years. History is distorted.”

Medvedchuk’s demand to ban the book is now a moot point — Справа Василя Стуса (The Case of Vasyl Stus) has already been published. However, it might be possible to extract sections or chapters in future editions, if Medvedchuk wins the court battle. Kipiani thinks the lawsuit is merely intended to frighten him and not to force an actual ban. Either way, it’s an attempt to limit the freedom of speech:

“There is a lawsuit against nine episodes of these articles that Medvedchuk considers to be damaging his ‘brilliant honor, dignity and business reputation’. For me, this is direct pressure on freedom of speech. Because among these nine points, seven are so-called opinion judgments; that is, there is nothing to dispute, because I think so and I am not going to give up my mind. As for the other two, there is a need to speak with lawyers who believe that it will be necessary to prove that something was not meant. All of these claims relate to my evaluative judgments about Medvedchuk’s role in the lawsuit, his personal qualities, his motives”

In the end, the ongoing influence of Medvedchuk in Ukraine troubles civil society — at the very least, it threatens Ukrainian integrity and security. But even more disturbing is the question of why nobody among Ukrainian Presidents and other high officials have tried to limit Medvedchuk’s influence. Perhaps his ties with Putin — his family ties, in particular — might provide an explanation.

Make me, O God, the noble collapse as the circle shuts;

There remains one thing: death to save the internally free;

free for themselves and for Ukraine

Now foresaw in delusional

Ukraine somewhere — there

all — in Anton’s flame

here in the east; we go from it

Good for her journey on which you will fall

and friends — also fall;

Prophecy fulfilled.

Vasyl Stus. Translation by

Read more:

- How Ukraine’s Vasyl Stus used poems to fight the Soviet Regime

- Remembering Soviet atrocities: Solovki and Sandarmokh

- They broke the Gulag: How Ukrainians overcame the Soviet repressive machine

- Russian police arrest Yuri Dmitriev, Karelian human rights leader

- The Kremlin and the GULAG: Deliberate amnesia