Vladimir Putin’s regime, which has always been authoritarian and kleptocratic, nonetheless has evolved over the course of the last 18 years through four stages and now is entering its fifth and final one, according to Moscow commentator Igor Yakovenko.

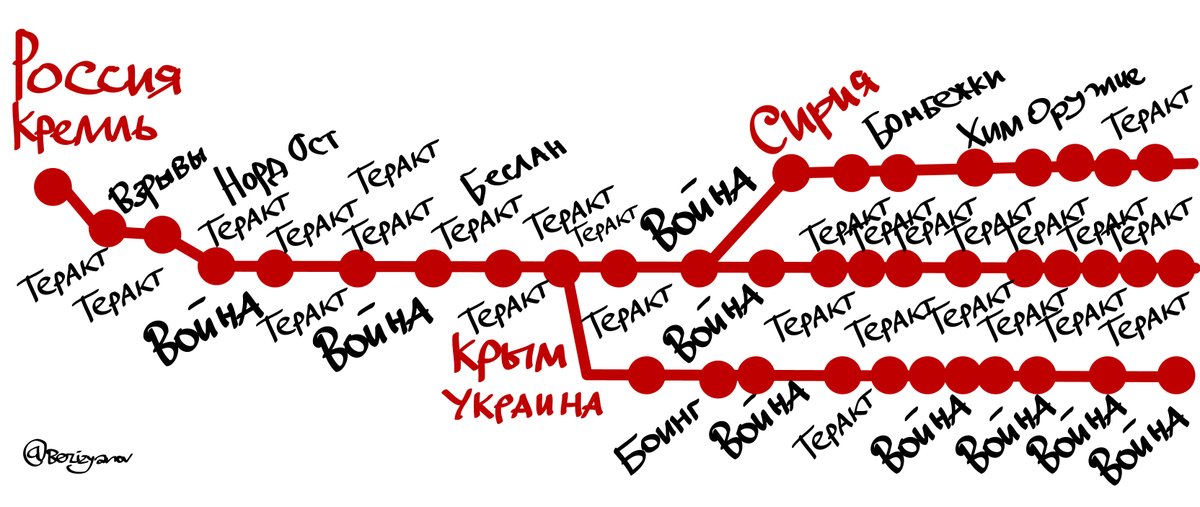

The first period lasted from 1999 to 2003, having begun with the blowing up of apartment buildings and the start of the second post-Soviet Chechen war, had as its “main event” the destruction of independent mass media, something that allowed Putin to make the lie the basis of his power, the commentator says.

The second period (2003-2007) involved “the destruction of private property and the transformation of corruption” into the key feature of the regime. That was accompanied by the “cleansing of the political field” and remarks like “parliament is not a place for discussion.” As in the first, “the world didn’t understand anything” about what Putin represented.

The third period (2007-2014) extended from the Munich speech to the Crimean Anschluss and aggression against Ukraine. In this period, “the Putin regime ceased to be a problem of Russia alone and become a problem of the entire world.” As a result there was a partial return to the cold war and a search in the West for an explanation of Putin’s behavior.

The fourth period, one of “an imagined empire,” lasted from 2014 to 2016, from the Crimean Anschluss in 2014 to “a series of foreign policy failures of the end of 2016 and the beginning of 2017. Putin conducted “’wars for television,’” and he promoted a series of “imperial myths” taken from the past but projected on to the future.

During that period, Yakovenko points out, “Russia was excluded from the G8 but with the help of television imagined itself as a world empire.” The West “began to understand that Putin’s Russia is the main threat for humanity” but “nevertheless felt compelled to conduct negotiations” with it. After Brexit and the victory of Donald Trump, Russian television shifted from the idea that “Crimea is ours” to notion that “the world is ours.”

But then things began to go wrong, the commentator says, and the Putin regime entered its fifth period. Trump turned out to be something other than Putin expected. “The main hero of Brexit by the name of Boris suddenly became the chief supporter of anti-Russian sanctions.” And Russian military actions in Syria highlighted not Moscow’s strength but its weakness.

Moreover, a series of developments in Europe have shown that despite everything Russia can do in the propaganda sphere, there are definite limits to its influence, given the realities that ever more people in the West can see. Montenegro is now in NATO, and “the Balkans are lost for Putin.”

In Austria, the Kremlin’s preferred candidate for president lost, thus “depriving Putin of support in Central Europe.” The elections in the Netherlands deprived Moscow of yet another supporter in Europe. And the French elections served up a crushing defeat for Putin’s preferred candidate Marine Le Pen. There is little reason to think Putin will win the German elections.

And according to Yakovenko, Putin has even called particular attention to these losses by his support for his defense minister Sergey Shoygu’s construction “for 20 billion rubles” of a plywood Reichstag in a Moscow park so that Russian children could “storm” it. Hardly an advertisement for Putin’s success.

In short, Putin’s Russia is in its fifth and final stage. When it will end is as yet unclear, but that it will end is certain because in so many ways, Putin’s regime recalls that of the Soviets in the 1970s and 1980s, a time when what propagandists said and what people saw diverged so much that the regime became unsupportable.

Related:

- Since 1945, Moscow has been involved in a military action on average every 2 years

- “Syrian strikes transform Trump from ‘ours’ to ‘another Hillary’”and other neglected Russian stories

- ‘Spetsnaz of the USSR’ – the new Russian irregulars in Syria now fighting for Assad

- Chechen and Afghan echoes of Putin's military operation in Syria

- 'The Chechen War isn't over'

- Ukrainian War far more dangerous for Russia than even the Chechen War, Nevzorov says

- Chronology of the annexation of Crimea

- West fails to recognize nature and scope of Putin's hybrid war against it, Eidman says

- Can there be another coup in Montenegro?

- How the Kremlin influences the West using Russian criminal groups in Europe