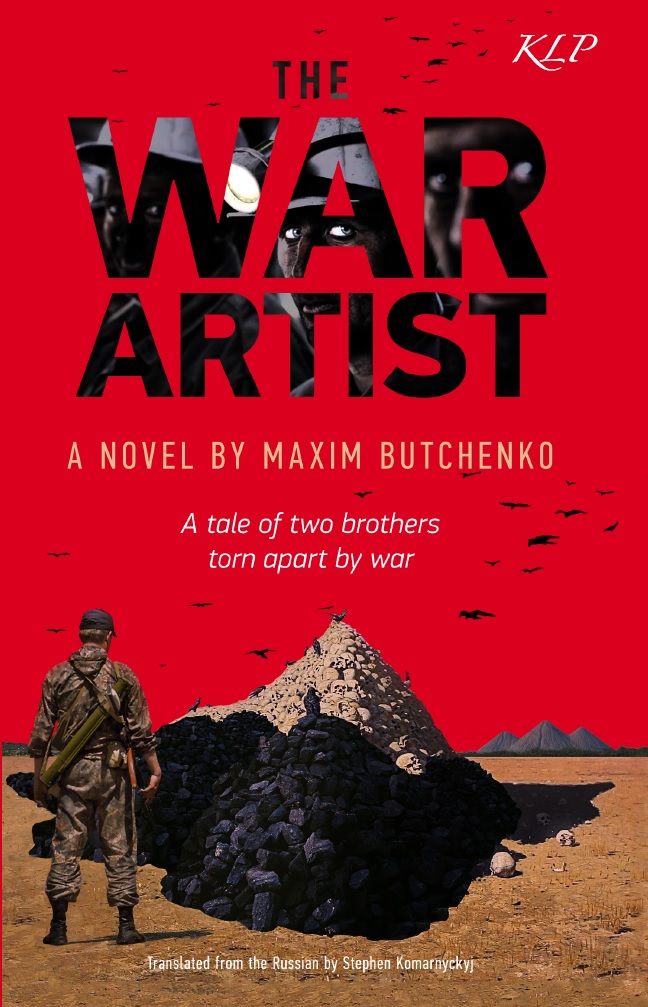

What makes a man betray his country? Maxim Butchenko’s novel The War Artist explores this question against the backdrop of a war forgotten by Europe.

As I write this introduction in February 2017 shells are raining down on a city in Adviyivka, a European city. A 24-year-old ambulance driver has been killed overnight. A Russian shell landed next to his vehicle and his brains are smeared onto its ceiling. Civilians huddle in tents in temperatures of – 20 c around field kitchens were the Ukrainian army doles out hot food.

Nolan Peterson an ex-US Special Forces pilot turned journalist says he has never seen fighting as intense as he has witnessed in Ukraine. The Russians currently deploy more tanks in the Donbas than the entire Czech French and German armies combined. The war has claimed 10,000 casualties by some estimates. However, a German intelligence report which emerged in February 2015 gave a figure of 50,000 .

Yet the conflict is often misunderstood largely due to Russia’s ability to manipulate western media by distributing stories through manipulated journalists and corrupt politicians. This introduction explains the origins of the war and its implications for the West.

Read also: How Russia’s worst propaganda myths about Ukraine seep into media language

The Donbas in East Ukraine is a vast rolling expanse of Steppe where the horizon is broken by collieries and slag heaps. Miners work with primitive equipment and are often maimed and killed. They see the corpses of their colleagues carried to the surface and draped with a sheet on a weekly basis.

The area was the site of what Luhansk native Maxim Butchenko a Soviet experiment after world war two. Cities were built according to a strict Soviet model and miners often ex-convicts were shipped in from across the Soviet Union. Some areas retained a Ukrainian identity but many became soulless enclaves of Marxism-Leninism.

The area was the site of what Luhansk native Maxim Butchenko a Soviet experiment after world war two. Cities were built according to a strict Soviet model and miners often ex-convicts were shipped in from across the Soviet Union. Some areas retained a Ukrainian identity but many became soulless enclaves of Marxism-Leninism.

After the Soviet Union collapsed the area became a kind of wild east where organized crime flourished. Business rivals were assassinated and crime bosses donned lounge suits and posed as ordinary businessmen while sending thugs in ski masks to beat up or kill their enemies. Oligarchs with shadowy pasts soon owned the area's mines and industries. Two of them, Renat Akhmetov and Viktor Yanukovych went into politics.

Yanukovych won a presidential election by means of massive voter fraud (including multiple voting by the same people and support from dead voters) in 2004. Massive crowds took to the streets in Kyiv to protest and the result was canceled. Yanukovych tried to organize his own demonstrations. He and his cronies bussed in miners from the Donbas. They were told that the rest of Ukraine was Fascist. The soviet mindset which had survived in the Donbas had fossilized like the coal beneath its vast plains. Its inhabitants were only too willing to believe the fairy tale of Fascists ruling Kyiv. Yanukovych lost the subsequent rerun but despite massive evidence of fraud he and his cronies were never prosecuted.

He won a presidential election in 2010 aided by an American consultant Paul Manafort who managed to present this burly Mafioso as a slick technocrat. However, Yanukovych soon tore off the mask crafted by Manafort and soon imposed perhaps the most corrupt regime in history on Ukraine.

During 2010 to 2013 businesses were seized by a small gang of his cronies collectively known as “The Family.” State tenders were won by forms linked ultimately to him or his entourage. Opposition politicians were jailed on bogus charges. However, Ukrainians believed that he would keep his promise to sign an association agreement with the EU. They thought that he would have to hold fair elections to have any credibility with the Europeans.

When Yanukovych refused to sign the agreement in 2013 students demonstrated on Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Kyiv’s main square. They knew now that Yanukovych would try and stay in power and loot the country indefinitely. He sent thugs in uniform to crush the protests and ultimately inflamed them. Activists were kidnapped and murdered or died under sniper fire. Yanukovych ultimately fled the country with the aid of his patron Putin in March 2014. Russia sent Special Forces into Crimea and organized a fake referendum to legitimize its occupation. Special Forces went into the Donbas and seized public buildings. There were already demonstrations organized by Yanukovych’s Party of the Regions. They whipped together crowds of workers from their enterprises as they tried to hold onto power in a region they regarded as their own personal bailiwick.

Read also: How it all happened: from Euromaidan to the occupation of Crimea and war in Donbas

Russia was able to recruit some of these workers into hybrid forces comprising a mixture of locals and Russian mercenaries. They set up two pseudo-republics, the DNR and the LNR, in Donetsk and Luhansk. These were led by shadowy characters, Nazis like Pavel Gubarev or GRU agents like Igor Strelkov. Fake countries created by Russian intelligence and its deniable assets. The hybrid army was used as cannon fodder by the regular Russian army who were in Ukraine from 2014 onwards despite the brazen lies of the Kremlin. There is no genuine separatist movement in Ukraine. There is the Russian army. There are some Ukrainians and multinational mercenaries in Russian-led units.

Russia had hoped to split Ukraine apart in 2014 believing that many people across south and east Ukraine would flock to their banner. This operation, known as the “Russian Spring," or "Novorossiya," failed dismally because Ukrainians remained loyal to their state and understood Putin’s kleptocracy only too well. Putin was left occupying part of the Donbas.

Read also: Meet the people behind Novorossiya’s grassroots defeat

Maxim Butchenko’s novel begins at the point where Russian Special Forces are seizing buildings and destabilizing Luhansk.

It exposes how Russia inflamed the conflict and used bamboozled locals as a cover for its invasion. Anton Nedelkov is a miner whose dreams of becoming a painter are frustrated. The book explores what motivates his betrayal of his country in a non-judgemental manner.

The war is, as Nolan Peterson says, a destination. You can sit on a café veranda in Kyiv and watch the wind flurry your cappuccino then catch a train hundreds of miles east to the combat zone. However, Putin’s aim is to wreck the west and transplant his oligarchic society across Europe and the EU. Those miners who betrayed their country live in poverty while criminals cruise the streets in Bentleys. The majority of the population in the occupied areas are simply terrorized into compliance. They only know of the world outside through media outlets controlled by oligarchs. This world sees as remote and unreal as if glimpsed through the wrong end of a telescope. However, the gold doors of Trump tower could just as easily adorn one of Putin’s many obscenely opulent palaces.

This book is a glimpse into Ukraine’s present but also into one potential future for the West. We stand at a crossroads and must choose wisely. Or we will end up like Anton in darkness, deeper than that congealed within the fossil coal of the Donbas.

More about English translations of Ukrainian literature:

- Ukrainian translations, Russian oppression, and soft power

- “Rebellious pagan” Ukrainian poet Antonych receives English translation

- A XIX-century poet is now Ukraine’s driving force of change

- Ukraine’s Executed Renaissance and a kickstarter for one of its modern successors

- Let the songbird out of the cage – vote for Ukrainian literature

- Ukrainian book on “little things in life” seeks to reach the English reader

More by Stephen Komarnyckyj:

- Putin’s propaganda machine and how to smash it

- A strategy for damaging Russia’s propaganda machine

- Dancing with Stalin. The Holodomor genocide famine in Ukraine

- How Russia’s use of deniable assets bamboozled western security services

- Fancy a frack? How the UK Greens got into bed with Putin