“Protective” invasion?

In conventional understanding, World War II began on September 1st, 1939, when Nazi Germany launched its invasion of Poland. On the 17th, Nazi Germany was joined by the USSR when it began its invasion of Poland.

On the 20th, a debate on the war situation was held in the British Parliament. Of note in this debate, Robert Boothby MP rose up and claimed:

“I think it is legitimate to suppose that this action on the part of the Soviet Government was taken […] from the point of view of self-preservation and self-defence” on the basis that “the action taken by the Russian troops […] has pushed the German frontier considerably westward.”

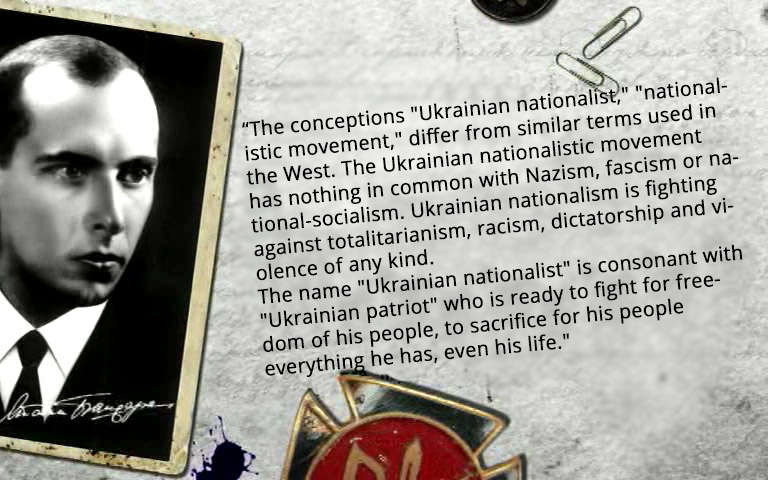

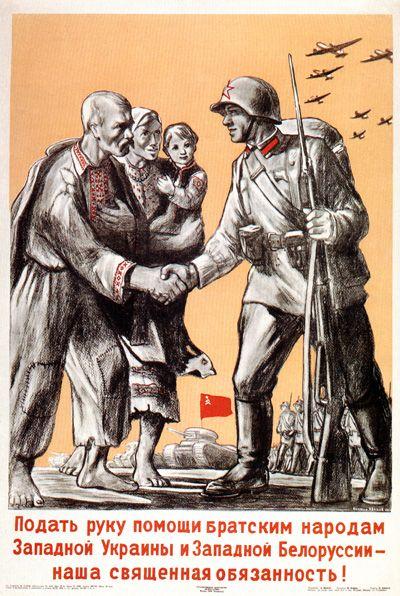

As the Red Army was moving its tanks on the 17th, the Polish Ambassador to Moscow, Wacław Grzybowski, was handed a note stating that Poland had ceased to exist, that this had rendered Polish-Soviet agreements such as the 1932 non-aggression pact null and void, and that the Red Army was moving into Poland in order to “protect” its Belarusian and Ukrainian populations. [1]

This line helped form the theme of how Western newspapers covered the initial Soviet invasion. Chicago Tribune, for example, had as its front page on the very next day the headline “Reds Invade Poland: Russians cross border to ‘protect minorities.’”

In the occupied city of Brest-Litovsk on September 22nd, Soviet forces participated in a victory parade and marched under a banner that read:

“Long live the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, the liberator of laboring masses of W[est]B[elarus] and W[est] U[kraine]!”

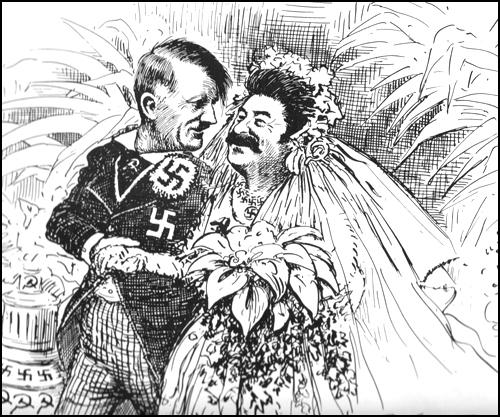

Soviet forces were marching along with the Germans, and not just under this banner but also under German flags. It was a joint victory parade in a very symbolic city. This was where on March 3rd, 1918, the Bolsheviks signed a peace agreement with Imperial Germany taking Russia out of World War I.

A wishful war

To understand why the USSR invaded Poland, one must understand the diplomatic context as well as Soviet philosophy, which is not taken into account by the conventional understanding of the invasion as “defensive” or “protective.” Stalin’s motivations were, in fact, much more sinister.

Stalin, like Lenin before him, took much of his inspiration from Marx and Engels. Far from being a deviation from Communist thought as certain Trotskyists have claimed, Stalin was at the very least a holder of thoughts that represented a continuation of Lenin’s rule in a number of key areas, including the beliefs in global domination and that war, even world war, was a necessary mother to progress.

On that latter theme, Engels wrote in 1887:

“No war is any longer possible for Prussia-Germany except a world war and a world war indeed of an extent and violence hitherto undreamt of. Eight to ten millions of soldiers will massacre one another and in doing so devour the whole of Europe until they have stripped it barer than any swarm of locusts has ever done. The devastations of the Thirty Years’ War compressed into three or four years, and spread over the whole Continent;

famine, pestilence, general demoralisation both of the armies and of the mass of the people produced by acute distress;

hopeless confusion of our artificial machinery in trade, industry and credit, ending in general bankruptcy;

collapse of the old states and their traditional state wisdom to such an extent that crowns will roll by dozens on the pavement and there will be nobody to pick them up;

absolute impossibility of foreseeing how it will all end and who will come out of the struggle as victor;

only one result is absolutely certain: general exhaustion and the establishment of the conditions for the ultimate victory of the working class.”

For Lenin and Stalin, these “prophetic words” were proved correct in 1917 when they found power laying on the streets of St. Petersburg after Tsar Nicholas II had abdicated and after Alexander Kerensky had pledged to continue involvement in a war that was driving his country to economic ruin. Likewise in 1917, Communist revolutionaries were gathering pace in Germany and Hungary in the wake of their collapsing economies.

The end of World War I was not only marked by violence directly caused by the increasingly radical Left and Right forces, but the treaty of Versailles, which ended the conflict, was also marked (in theory at least) by the principle of national self-determination in mind. This meant an independent Polish state for the first time in 123 years. It also meant independence for the Baltic peoples along with Finland and Ukraine, which had been colonies of the Tsarist Russian Empire.

Polish barrier to the Bolshevik expansion

Poland’s new leader Józef Piłsudski might have been a socialist but he was not a Soviet socialist. Somewhat ironically, Marx and Engels during their lifetimes supported Poland for its revolutionary potential but now, in the eyes of the most important Communist leaders in Russia, Poland provided a stumbling block to the fantasized world revolution.

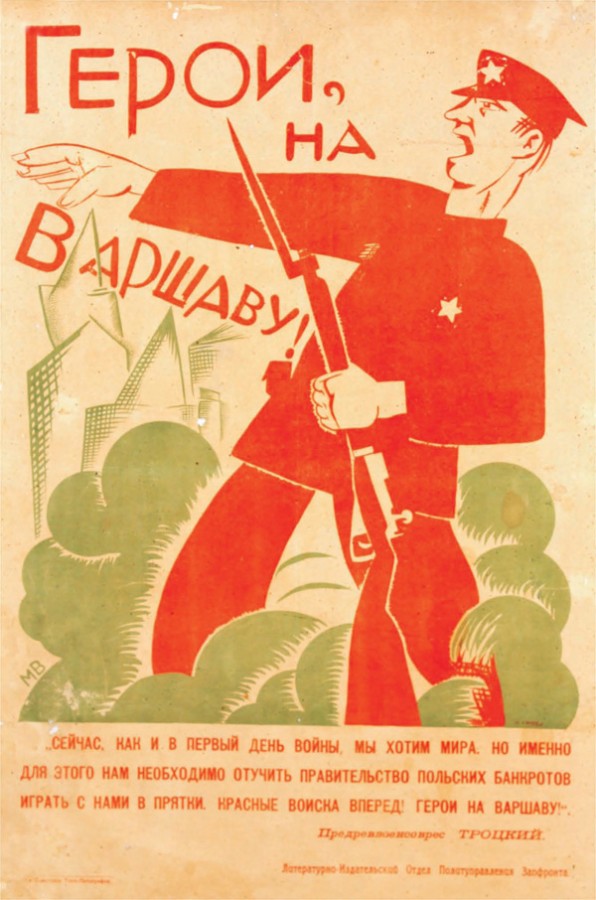

Exploiting the fact that in 1919 the Polish-Russian border was as of yet not fully defined, Lenin ordered his burgeoning Red Army troops to probe the Poles, to see how far they could get before they encountered resistance.

In the early hours of February 14th, 1919, a Red Army encampment was intercepted by Polish cavalrymen at the village of Bereza-Kartuska (now Byaroza, Belarus). This was the 1st engagement of the Polish-Soviet War of which there is an excellent history by Professor Norman Davies. Lenin’s attitude towards Poland is best exemplified by the words of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, commander-in-chief of the Red Western Front, to his men. “To the west!” he barked. “Over the corpse of white Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration.” [2]

Here it must be noted that Lenin’s wars of reconquest, which after a long struggle ultimately consumed Ukraine and the Caucasus but failed to reconquer Poland, Finland, and the Baltics, were concurrent but not a part of the (typically defined) “Red vs White” Russian Civil War.

Reflecting on the outcome of the Battle of Warsaw during the conflict, Edgar Vincent D’Abernon, British ambassador to Berlin, remarked that the Poles had saved Christendom and Western civilization from certain imperilment. [3] On the Soviet flipside, the failure to capture Poland represented a missed opportunity, which prompted the birth of “Socialism In One Country.” In ideological terms, the Soviet regime justified Socialism in One Country on the basis of building up a base within the USSR on which to lead the described “world revolution” and to export it at some future time.

Even though Polish-Soviet public diplomacy during the mid-30s might have been marked by the aforementioned non-aggression pact, at no time did this mean the idea of conquering Poland (or, indeed, other territories that used to be a part of the Tsarist Empire) into the Communist banner was ever fully abandoned. In 1939, Hitler simply gifted Stalin a golden opportunity to fulfill an old wish.

All the meanwhile, during the 1920s, the USSR began to pursue economic deals with Western nations, the most notable of which involved that other “pariah state” of Europe: Weimar Germany. As Gerherd Weinberg observes, “Hatred of Poland was a major factor in bringing Weimar Germany and the Soviet Union together.” [4]

Read the following part: Hitler’s Anschluss