Historians have often observed that one of the fundamental weaknesses of tsarist Russia was that the country was held together only by personalist ties of loyalty to the tsar and so that when the tsar was removed from the equation, Russia had little or no reason to continue to exist.

And more recently, commentators have routinely pointed out that Chechnya is linked to the rest of the Russian Federation only on the basis of the personal loyalty of Ramzan Kadyrov to Vladimir Putin, an arrangement that the actuarial tables make clear cannot possibly last forever.

Now, Russian commentator Oleg Kashin argues that this pattern holds for the peoples within the borders of Russia as a whole and that “except for mass loyalty to Putin personally, the peoples it unites have nothing in common,” something that makes that state’s future anything but secure.

“In the West,” he writes, “Vladimir Putin is often called a nationalist, but in Russia such a title sounds ambiguous as does the very word ‘nation.’” The political class in post-Soviet Russia rejects nationalism as a form of “ultra-right-wing radicalism” and thus not something on which the state must rely.

The problem of defining the people of Russia only intensified with the annexation of Crimea. Moscow talked a lot about an ethnic Russian world, but it became increasingly obvious that a more appropriate term would be a civic Russian world – even if that did not correspond to the emotional needs of ethnic Russians.

That is because the term “civic Russian” can be used for a Chechen or a Buryat and not just an ethnic Russian. But both these nations and other non-Russians, not to speak of many ethnic Russians aren’t comfortable with the idea of sacrificing their national identities as peoples for something else.

In the aftermath of the Soviet collapse in 1991, “post-Soviet Russia was concerned with a plethora of much more immediate issues than nation building,” Kashin says. And as a result, it retained “the Soviet administrative divisions, the most important characteristic of which were national autonomies,” in which ethnocracies rapidly arose.

“Their existence,” he continues, “do not allow Russia to be called a state of the ethnic Russian people: official rhetoric uses the term ‘multi-national state’ presupposing that Russia belongs to all the ethnoses which are included within it.” And “at this stage, nation building stopped in 1991, possibly forever.”

For Russians to this day, the word “nation” retains its ethnic content and even suggests to most something related to background by blood. That is why the Soviets introduced the concept of “the Soviet people,” an identity that was not so limited and that was supposed to supplant ethnic identities over time.

According to Kashin, “the bankruptcy of this theory became manifest under Mikhail Gorbachev when ‘the Soviet people’ in Azerbaijan and Armenia began between itself a real inter-ethnic war.” It became clear that national identities had not disappeared or even grown weaker.

That pattern has been replicated in the period since 1991 in the fighting between Ingush and Ossetians as well as in other conflicts. For the time being, such “inter-ethnic contradictions are suppressed by a strong centralized power; and Vladimir Putin evidently understands this perfectly well.

Putin almost certainly would like to be a nationalist if only he could create a nation. But that isn’t happening. As long as he is in power, the personalist ties of the peoples of the Russian Federation will likely hold the country together; as soon as he isn’t, the prospects that such arrangements will continue decline precipitously.

Related:

- Putin’s drive to build totalitarianism with political technology alone collapses, Eidman says

- Putin’s ‘real but Pyrrhic victory’: infecting the world with distrust and division

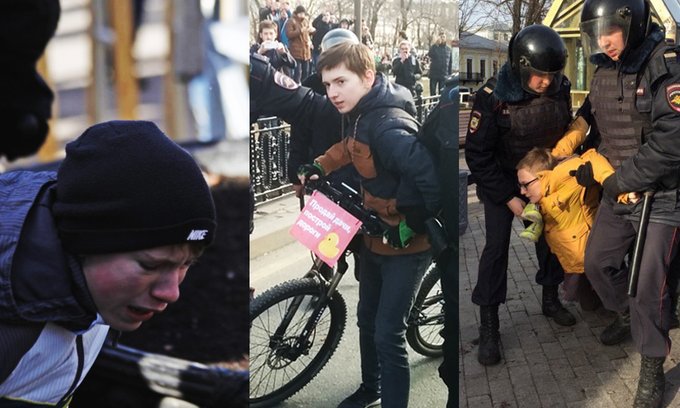

- New Reichstag for Moscow children to storm — ‘a universal meme’ for Putin’s Russia, Movchan says

- Putin’s Russia pursuing ‘survival by paradox,’ Shevtsova says

- Putin now fears a threat he helped create – 4,000 Russian citizens fighting for ISIS

- ‘There are no liberals in Putin’s Kremlin,’ Barbashin and Inozemtsev say