The Russian propaganda machine produces endless streams of fakes and manipulative stories. While at times they may seem outrageous or silly, they are far from being random. Russian propaganda for both domestic and foreign audiences follows techniques that stem from Goebbel’s times. Ultimately, it is a weapon of war. In our series A guide to Russian propaganda, we examine how propaganda works, and how one can avoid falling for it.

One of the ways Russia achieves national goals is by creating falsifications and conspiracy theories."The truth becomes one of many possible competing theories, just one of several alternative realities. It messes with people’s minds and that’s what it’s designed to do." - Liz Wahl, former RT anchor

When Russia wants to, it can create high-quality fakes and sophisticated deceptions with brilliant intricacy, like operation INFEKTION or the moon landing hoax. But when something goes wrong in Russia’s wars abroad, there’s no time. Quick and dirty conspiracy theories and disinformation slow down analysis and distract people in the early stages of a news story.

Just recently, Russia used this tactic to hide its bombing of a UN humanitarian aid convoy delivering food and medicine to Syria, which was bombed on 19 September 2016, with 21 people killed and aid for 78,000 people destroyed. Since that part of Syria is controlled by the joint Rusian-Assad forces, the suspicions fell on Russia.

First, Russia’s Ministry of Defense claimed on 20 September that a mortar was moving with the convoy, suggesting either the convoy was protecting a “terrorist” truck, or that terrorists had attacked the convoy. However, this was easily debunked by Conflict Intelligence Team, which proved the truck shown on the MoD's video was filmed 6 km away from the bombing site, 5 hours before the incident.

Then, Russia's MoD claimed that the convoy wasn’t destroyed by an air strike at all. But it was obvious from the photos that only an air strike could leave those kinds of holes in the destroyed vehicles.

Then Russian propaganda suggested a US drone was responsible for the bombing - which was the total opposite of the previous version, but it does dovetail with recent fears of US overreach with drone warfare.

But photos from the site showed the tails of OFAB 250-270s, Russian-made bombs used by the Syrian and Russia air forces and not used by NATO forces, sticking out of the wreckage.

Russia’s domestic media immediately created more theories, first saying that it was Assad, then that it wasn’t, that it was a US plot, that it was the Syrian rebels. One even suggested there was no convoy in the first place, and that the whole story was a conspiracy against Russia.

Who attacked the UN humanitarian convoy in Aleppo? Here's what today's Russian papers are saying. pic.twitter.com/OBu8eCPoB8

— Steve Rosenberg (@BBCSteveR) September 21, 2016

Then, alternative outlets picked up the story from there - one said that it was the White Helmets–the rescuers!

Do you feel your head swirling already? That’s exactly the point! You are witnessing the birth of conspiracy theories. Since they’re being made up on the run, they contradict each other, creating chaos and confusion. Amateurs will take them up, weave them together, and produce new material that Russian propaganda can use later. In the meantime, specialists in Moscow are probably already working on the “official” deceptive story that will be much more airtight.

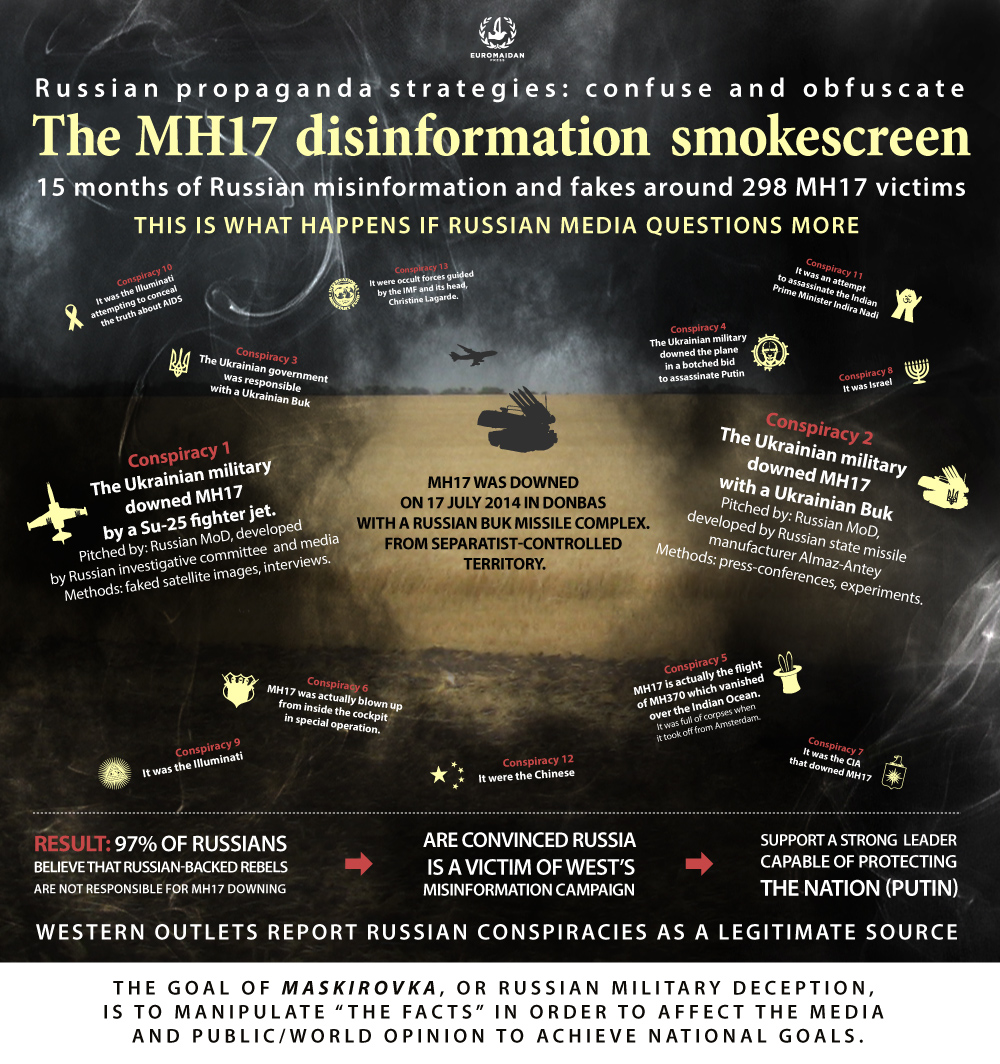

We’ve seen this before: on 17 July 2014, civilian airliner MH17 was shot down by a Russian Buk, operated by Russian servicemen invading Ukraine who were aiming for a Ukrainian military plane. But to obscure the facts, Russia produced multiple conspiracies.

Days after the crash Russia’s Ministry of Defense planted two theories that would later be regurgitated many times over: that it was either a Ukrainian plane or a Ukrainian Buk that shot down MH17. For this, it on 21 July 2014, it produced faked satellite images of a Buk that bellingcat proved were taken at least one month before the launch, and on 21 July 2014, fake radar data purporting to show a a Su-25 warplane 3-5 km from the civilian airliner. The Joint Investigation Team report later on showed that this was impossible and that the distance between the closest aircraft and MH17 was approximately 30 km.

Ahead of @mod_russia's #MH17 press conference this afternoon here's a reminder of their last press conference pic.twitter.com/D6UL7h3nqI

— bellingcat (@bellingcat) 26 вересня 2016 р.

Someone in Moscow even edited Wikipedia to make you think that SU-25s fly at the same altitude as airliner MH17 (which they don’t); and to make you think that Russia doesn’t use that same type of missile anymore.

Too bad Putin took a photo right next to it at a Russian military base in Armenia. The same rocket was displayed at a military parade in Chita, Russia, on 9 May 2015.

And other theories flooded the landscape.

Read more: The most comprehensive guide ever to MH17 conspiracies

Do all these theories work? Let's listen to Liz Wahl, former anchor at RT:

"Part of the strategy is to plant seeds of doubt to the official story and question everything so facts can’t be established. So no one really knows what’s fact and what’s fiction. What ends up happening is that the truth becomes one of many possible competing theories, just one of several alternative realities. It messes with people’s minds and that’s what it’s designed to do."

The Joint Investigation Team confirmed conclusively that MH17 was shot down by a Russian Buk, but Russia is still trying to sow a seed of doubt, accusing the investigation of bias, and that it’s all a conspiracy against Russia.

Rapid fire conspiracy theories distract people at the early stages of the story, concealing the most obvious and damning version of events.

Luckily, these conspiracies are produced so fast, there’s no time for a credible theory, and with the help of investigative journalists the truth will come out.

Related: Former RT anchor: I became the target of a Russian propaganda conspiracy theory

[hr]Scenario by Alya Shandra, Alex Leonore, graphics by Ganna Naronina, narration by Paula Chertok. Find more videos about Russian propaganda in our series A guide to Russian propaganda.