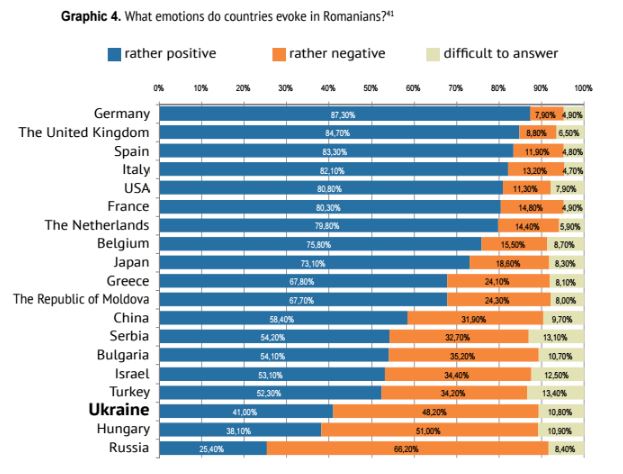

For a long time, Ukraine was positioned as an unfriendly state in the public space in Romania. The Ukrainian information space and political assessments reciprocated by generating a high level of suspicion, mistrust, and even hostility to the neighboring state.

2014 brought clarity to the situation. Russia, the country that had sworn eternal friendship, committed aggression against Ukraine, whereas Bucharest, which was sometimes perceived in Ukraine as possibly the main threat to national security, helped Kyiv.

The revival of Ukrainian-Romanian cooperation did not, of course, lead to settling the host of problems that were accumulated over more than 20 years of tense relations, but now there is at least hope for the development of trustful cooperation based on the security-first principle.

The emergence of a common threat forced the two countries to revise their relations, but it is too early to say that they have completely put distrust behind them.

Luggage of distrust

After 1991, the relations between the two countries revived but were affected by numerous conflicts.

The most important foundational document for bilateral relations was signed in 1997 – the Agreement on Good Neighborly Relations and Cooperation between Ukraine and Romania.

Romanian experts note that Bucharest wanted to show in this way that it had no territorial claims against Ukraine, which was essential in view of its desire to obtain candidate status for NATO membership.

The hottest debates hampering progress for both countries were about protecting the rights of the Romanian minority in Ukraine and those of the Ukrainian minority in Romania, the delimitation of the continental shelf in the Black Sea, creating a deep waterway between the Danube River and the Black Sea in the Ukrainian part of the delta, and the situation with the Kryvyi Rih Mining and Processing Works.

All these questions arose against a background of mutual suspicions of insincerity.

The Ukrainian authorities suspected that Bucharest intended to implement the Greater Romania project, while the Romanian leaders distrusted Kyiv’s multivector policy, which occasionally tilted more towards Russia, creating an additional source of anxiety.

2014 was a turning point in the relations between the two countries.

Similarly, an agreement on small border traffic was signed in 2014, which provided an opportunity for nearly 500,000 Ukrainians residing in the 30-kilometer zone on the border with Romania, to travel to the neighboring country without visas.

(It’s worth mentioning that negotiations about this had carried on since the beginning of Yushchenko’s presidency, however, no consent was given from the Romanian side – ed.)

Romania’s support for the Euromaidan and condemnation of Russian aggression against Ukraine largely determined the new dynamics in bilateral relations.

Over the past year, the two presidents met four times including that in 2015, when the Romanian President Klaus Iohannis was in Kyiv on an official visit.

Achievements that indicate a new spirit of cooperation include the opening of Romanian consulates in Solotvyno village in the Zakarpattia Oblast, cancellation of payment for long-term (national) visas, and joint border patrols to combat smuggling.

This list may grow longer, considering the desire of the leadership in both countries to establish transport links between the countries (direct railway connection between the two capitals, direct air connection, and the Chernivtsi-Bucharest bus route).

Unlike his predecessor Traian Băsescu, he is less burdened by historical legacy in his approach and rhetoric regarding Ukraine.

And the country’s global foreign relations policy changed, too. Romania, whose regional ambitions used to be limited to the Moldovan direction, is now emerging as a key player in Central and Eastern Europe and in the Black Sea basin, gradually taking over Poland’s position of a regional influencer.

Security above all

An awareness of common security threats was the reason for intensifying bilateral relations. Romania was not fully convinced by Ukraine’s pro-Western course and suspected excessive dependence of the Ukrainian ruling circles on Russia, but Bucharest reassessed challenges after the annexation of Crimea and the launch of hostilities in the Donbas.

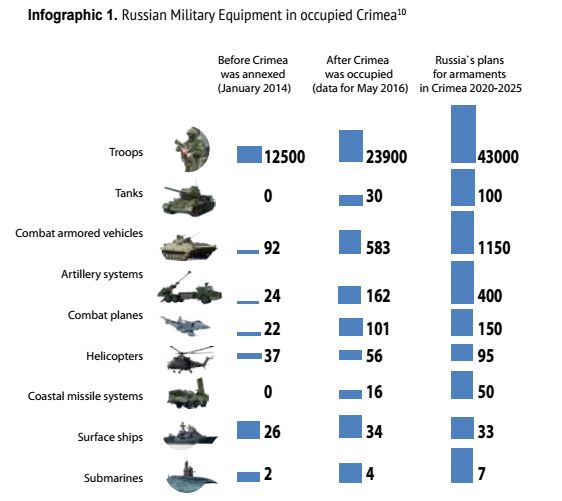

The militarization of Crimea, lying just 300 km off the coast of Romania, is turning into a major threat.

Russian aggression against Ukraine can’t remain unnoticed.

In April 2016, Russia conducted training over the Krasnodar region and the Black Sea involving the air forces and Black Sea aviation. They practiced an attack to block the Black Sea straits.

Moreover, after Romania and US launched the Deveselu NATO missile defense shield, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened retaliation, pointing out that Romania would be in the crosshairs.

Romania is a leader in coordinating regional efforts to build a security balance, which essentially means creating countermeasures to Russia’s provocative actions in the Black Sea. There is an initiative to create a NATO flotilla in the Black Sea with the participation of Romania, Bulgaria, and Türkiye. (However, Sofia has taken a cautious position regarding this issue.) Ukraine has expressed its desire to join in, and Georgia may follow suit if NATO accepts the Romanian initiative.

Therefore, Ukraine may become a connecting link in the regional security framework.

President Petro Poroshenko also came up with an idea to form a military brigade together with Romania and Bulgaria (following the example the Ukrainian-Lithuanian-Polish brigade).

Looking into the future

Security risks are the converging point of Ukraine’s and Romania’s interests. This does not mean that the two countries have forgotten the problems accumulated in the past. Obviously, Kyiv and Bucharest have decided not to bring them to the fore while faced with much bigger threats (Russia’s military machine, terrorism, and disintegation sentiments in the EU).

In any case, the parties are unable to avoid solving issues that have been on the agenda for over two decades. The involvement of a third party (international organizations) may be necessary. This approach may cause a barrage of criticism in Ukraine’s public space because Romania is perceived to have greater leverage on issues involving international arbitration. One often-mentioned argument in this context is Ukraine’s loss in the International Court of Justice in 2009 in a case versus Romania about the delimitation of the Black Sea. However, Ukraine and Romania may have no other solution than to turn to a third party.

Therefore, it is important to explore new avenues of cooperation between the two states, so that their bilateral relations are fully independent of Russian factor.

To this end, a series of recommendations could be considered:

SAFETY AND CYBERSECURITY. Ukraine should actively participate in Romania’s security initiatives. Adopt experience in cybersecurity. It is important to maintain dialogue on the creation of the Black Sea flotilla which would include at least one Ukrainian ship and a military brigade jointly with Romania and Bulgaria (following the example of a similar brigade formed with Poland and Lithuania). Participate in military exercises aimed at fighting in the conditions of a hybrid war and overcoming external threats.

UKRAINE-POLAND-ROMANIA TRIANGLE. Promote Romania’s regional initiatives on coordinating efforts in foreign policy, particularly establishing the Ukraine-Poland-Romania triangle.

EXPERIENCE OF REFORMS. Maintain close sectoral contact with Romania, particularly in combatting corruption. Organize active exchange of experience between Ukrainian and Romanian agencies for fighting corruption under the aegis of the EU.

ENERGY SECURITY. Implement mutually beneficial projects in the energy sector. Continue dialogue (learn the technical capacities) on the reverse delivery of Romanian gas to Ukraine as a priority project.

Romania has the third largest natural gas reserves in the European Union, importing 15% from Russia (85% of its demand is met by domestic production). As statistics about gas dependence are largely correlated with the political behavior of a country and its evaluation of Russian aggression against Ukraine, Romania’s energy independence can be an additional factor for placing this country among the logical partners of Ukraine.

SETTLEMENT BY ARBITRATION. Resolve existing problems in bilateral relations in the spirit of partnership as much as possible. If an understanding cannot be achieved, involve third parties, such as arbitration and international organizations (OSCE and the Council of Europe).

MINORITIES. Ukraine should ensure the necessary conditions for promoting the cultural rights of the Romanian minority. The activities of the Ukrainian side cannot be less than those implemented by the Romanian side regarding the Ukrainian minority.

NOT BY PRESIDENTS ALONE. Support the development of dialogue at different levels – not just between the presidents and governments, but also and especially at the parliamentary and civil society level. The two states should financially support conferences, workshops, and business aimed at facilitating mutual contacts.

CONDITIONS FOR TRADE. Both countries should focus their efforts on creating favorable conditions for the development of economic cooperation. Success in combatting corruption (using Romanian experience) could also encourage investors from Romania to enter the Ukrainian market. A series of business forums should take place between the two states in order to enhance economic cooperation at the level of SMEs.

MOLDOVAN FACTOR. Deepen cooperation with the Republic of Moldova and Romania to exchange views on reforming and preparing new ideas to strengthen the Eastern Partnership project.

TRANSNISTRIAN FACTOR. Continue dialogue regarding Transnistria settlement in the context of a common interest to limit Russia’s influence on the security situation in the region. Consider the creative approach of jointly ensuring the security of Moldovan air space provided that Chisinau agrees to this.

TRANSPORT CONNECTION. Contribute to solving transport connection problems, in particular regarding the launch of flights between Kyiv and Bucharest.

- Other materials from this series:

- How the Ukrainian-Polish partnership can pass the test of history

- Moldova – Ukraine’s problematic neighbor or partner on the road to the EU

- Foreign Policy Audit. Ukraine and Georgia are friends, but no longer allies

- Foreign Policy Audit. How to revive Ukrainian-Chinese relations

- Austria: a weak link in Europe or historical ally of Ukraine?