Seventy-five years ago today, when Stalin was Hitler’s ally, Moscow began the forcible deportation of tens of thousands of Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians from their occupied lands to the interior of USSR from which fewer than half returned alive, an event that continues to cast a dark shadow on these countries and their relations with Moscow.

The deportation from the three occupied Baltic countries of more than 40,000 people was the first mass action of its kind following Stalin’s Anschluss of those countries as a result of the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that made the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany allies.

Earlier senior officials in the overthrown governments of the three were arrested and exiled, most to their deaths. But on June 13, 14, 15 and 16, the Soviet occupiers gathered up as many Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians as they could according to categories that had been worked out long before 1941.

According to an article in “Estonian World,” that plan called for the deportation of all those in the following categories and their families:

- All the members of the former governments

- Higher state officials and judges

- Higher military personnel

- Former politicians

- Members of voluntary state defense organizations

- Members of student organizations

- Persons having actively participated in anti-Soviet armed combat

- Russian émigrés

- Security police officers and police officers

- Representatives of foreign companies and in general all people having contacts abroad

- Entrepreneurs and bankers

- Clergymen

- Members of the Red Cross.

Taken together, such people constituted 23 percent of Estonia’s population at the time. Similar measures were adopted and taken in Latvia and Lithuania.

What made this act of genocide even worse was that a large number of people were deported not because they were in these categories but because others wanted their housing or “to settle scores.”

The Baltic people subject to this degree had no appeal and only a single hour to pack before being loaded onto cattle cars. In Estonia alone, “Over 7,000 women, children and elderly people were among the deported … more than 25% of all the people deported in June 1941 were minors (under 16 years of age). [And] the deportations also severely affected Estonia’s Jewish population — more than 400 Estonian Jews, approximately 10% of the Estonian Jewish population, were among the deportees.”

The travails of those deported did not end there or even in the difficult places to which they were sent. At the end of the first year, special Soviet commissions came to the camps and settlements and had “hundreds of the detainees” shot. “By the spring of 1942,” “Estonian Life” reports, “of the more than 3,000 men dispatched to prison camps, only a couple hundred were still alive.”

Many not sent to the camps but rather classified as “forced resettlers” died of cold, starvation or overwork. The same pattern obtained for Latvians and Lithuanians as did yet another round of deportations from the Baltic countries in March 1949 after Soviet forces retook and reoccupied Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

This year, as they did privately in Soviet times and publicly after the recovery of their independence, the peoples of these three countries are marking this day as a memorial to those who were expelled and died. Fortunately, they are now being joined by others who have pledged themselves never to forget what Moscow did.

Today the justice ministers of the three Baltic countries together with their counterparts from Poland and Ukraine issued a joint statement declaring that “history cannot be changed or forgotten especially because today there are still living witnesses of the crimes that were committed.

The five ministers pointed out that the Soviet Union by this act and others as well sought to deprive people of their spirit and memory of independent statehood. “However, [even such] crimes against humanity cannot destroy spirits striving for freedom,” despite the continuing efforts of some to deny what happened.

The five decried that “the official rhetoric of Russia remains what it has always been: the crimes are denied and the Soviet past and its leaders are praised to the skies.” Those who remember the deportations of June 1941 know just how wrong and even ill-intentioned such claims are.

But perhaps the highlight of this day of memory was the visit of Crimean Tatar singer Jamala [the winner of 2016 EuroVision Song Contest – Ed.]to Vilnius and her meeting with Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite, a meeting that a Russian commentator condemned.

Day of remembrance of mass deportations of 1941 with @jamala. Soviet crimes will never be forgotten pic.twitter.com/jmVrBSejdx

— Dalia Grybauskaitė (@Grybauskaite_LT) June 14, 2016

The Lithuanian leader said that it was entirely appropriate that the Crimean Tatar singer who won the Eurovision contest with her song recalling the deportation of her people by the Soviet government should be in Vilnius on the 75th anniversary of the first mass deportations of Lithuanians and other Baltic nations by the same government.

Jamala’s coming on that day, she said was “symbolic” of the fact that “soviet crimes will never be forgotten.”

Related:

- Kremlin ‘really thinking about occupying Baltic countries,’ former RISI expert says

- Moscow seeking to subvert Baltic conservatives with “family values” campaign

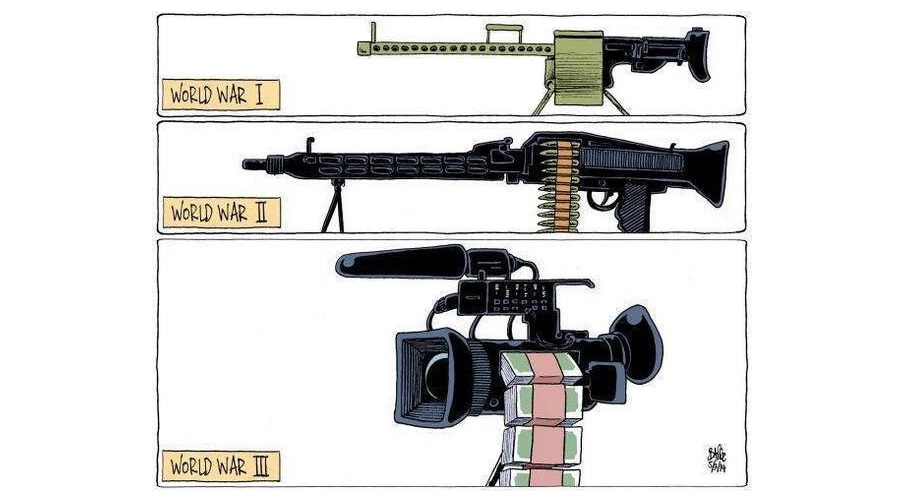

- Internet, not TV, now Moscow’s main propaganda channel for Baltic countries, Lithuanian expert says

- Kasparov on the breakup of Russia, invasion of Baltics and end of Putin’s regime

- Could a Baltic-Black Sea Alliance be taking shape

- Confirmation: NATO is not able to defend the Baltic States

- Russian coverage of Jamala’s victory descends to the level of old Soviet anecdote

- ‘Jamala glorified Ukraine and Crimea!’ — Crimeans on Jamala’s Eurovision win

- 8 shades of Jamala, Ukraine’s Eurovision contestant