Why Russia was sanctioned

It was the US who imposed the first batch of the Ukraine-related international sanctions on Russia as then-President Barack Obama signed an executive order called Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine on 6 March 2014 amid the unfolding Russian occupation of Crimea. In a matter of two weeks in Crimea, Russia held what it called a referendum, illegal under Ukrainian laws and not recognized by the international community. The next step was claiming independence of the peninsula from Ukraine as the result of the plebiscite and immediate annexation of this Ukrainian region by Russia.

The ongoing Russian attempt to redraw the internationally recognized borders, first of its kind since World War II, led to targeted sanctions against Russia introduced by the US, the EU, and Canada. The countries introduced sanctions on 17 March 2014, the day after the sham referendum and hours before Russian President Vladimir Putin recognized in his decree independence of Crimea, creating the formal premises for its subsequent annexation.

Later in the same month, Japan and Australia announced their sanctions against Russia, and the US government expanded its restrictions.

On 27 March 2014, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution A/RES/68/262 "Territorial integrity of Ukraine," calling upon all states and international organizations

“not to recognize alteration of the status of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol... and to refrain from any action or dealing that might be interpreted as recognizing any such altered status."

In the next month, Ukraine, Iceland, Albania, and Montenegro supported the EU restrictions against Russia.

As Russia expanded its aggression against Ukraine to the Donbas region by unleashing war in the area, more Russian individuals and organizations faced sanctions, and more countries supported these restrictions. Further on, the Kremlin remained reluctant to obey the international laws, which resulted in subsequent extensions of the sanctions in the following years and several Russian defeats in the international courts. Moreover, even more sanctions were introduced, such as those for Russia's use of the military-grade nerve agent on the British soil, its malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, and illicit trade with North Korea.

In total, the lists of legal entities under the Ukrainian, US, and EU sanctions include 1,270 enterprises, political and military organizations, with the Ukrainian lists including 1,137 legal entities, the US one with 469 o them, and the European lists of 68.

The Russian occupation regimes continue their crackdown on Crimean Tatars - the indigenous people of Crimea - and on pro-Ukrainian activism of any kind in both Crimean and Donbas regions.

Since the sanctions not only affected the Russian economy but also backfired on the countries that had introduced them when Russia enacted its own sanctions in retaliation, there is a growing chorus of opinions that the sanctions are not effective and should be lifted as Russia doesn't seem willing to fulfill the demands anyway.

What impact do international sanctions have on Russia and should the international community ease or even lift them?

Russia has been trying to use any opportunity to advocate the lifting of the sanctions and the authors of the report believe that

“It is no coincidence that the first thing Russia did when the [COVID-19] pandemic began was to attempt to use this factor to have the international sanctions lifted.”

Sanctions increase Russian spendings on Crimea

The authors of the report predict that highly-subsidized Crimea is going to face even more financial difficulties in the wake of the coronavirus crisis and the collapse of the oil prices that are going to cause economic and budgetary issues for Russia.

How much money does Russia dole out to Crimea? Citing the lack of a specific methodology to calculate the total spendings, the authors, however, list the confirmed articles of expenditure that include:

- the annual subsidies to the Crimean and Sevastopol budgets that make an average of up to $3 billion a year; the state subsidies account for 67.4% of the budget of Crimea and 57.4% of the budget of the city of Sevastopol, placing Crimea among the most-subsidized Russian regions;

- at least $12 billion spent on building the Kerch Strait Bridge and various road infrastructure projects on the peninsula;

- undisclosed costs for maintaining federal officials in Crimea;

- an undisclosed particular "Crimean line" in Russia’s military budget.

Before the war in 2013, some 66% of people traveled to Crimea by railway and 24% using the highways, the cargoes arrived by road (70%), and by train (24%). Sea and air traffic were insignificant before the occupation in Crimea. With sanctions, Ukraine and international organizations introduced elements of a continental blockade of Crimea from mainland Ukraine since the spring of 2014, which contributed to the Russian financial burden since the Kremlin had to ship everything in Crimea exceptionally by sea and air.

Russia’s indirect losses from sanctions “hundreds of times heavier” than direct costs

According to the report, the indirect losses Russia incurred as a result of the international sanctions for the occupation of Crimea and its subsequent aggression in the Donbas are hundreds of times heavier than direct costs spent for occupied Crimea.

An example of such "indirect losses" is a $200 billion decline in fixed capital investment in Russia in 2014-2015, when the sanctions were introduced:

The authors note that even in the current economic situation Russia is going to sustain high levels of military spending on its Black Sea Fleet based in Crimea which, given the economic downturn, is going to decline the living standards that are already low in occupied Crimea.

Another factor of the indirect losses is the suspension of economic cooperation with Russia that disrupted development and manufacturing at Russian enterprises dependent on imports. For example, as Russia didn’t receive German and Ukrainian ship engines due to the sanctions, its military shipbuilding program failed. The state policy of “import substitution” aimed at revitalizing the projects hit by the sanctions didn’t bring any results in this particular case.

However, the US thinktank FAS says in its January 2020 report,

“Overall, more than four-fifths of the largest 100 firms in Russia (in 2018) are not directly subject to any US sanctions, including companies in a variety of sectors, such as railway, retail, autos, services, mining, and manufacturing.”

Meanwhile, given that the major source of Russia’s export revenue is oil, the Russian leadership often has time to partially neutralize the effects of sanctions to some extent when the global price of oil grows up.

Sanctions thwart the further absorption of Crimea into Russia

Another major implication of sanctions is that they prevent Crimea's further absorption into Russia. As Ukrainian banks stopped operating in Crimea back in 2014, Russia had to recreate the financial system on the peninsula while trying to avoid the operations of its major banks in Crimea since they would have risked becoming a target for new sanctions.

At present, there are only 6 Russian banks still operating in Crimea compared with 36 in the first years of the occupation. All of them are now under sanctions.

"Banking sanctions make it impossible to invest in Crimea, even when it comes to private Russian investment, or use international payment systems and other financial services," the report's authors note.

As Ukraine officially closed the ports of occupied Crimea, international sea traffic dropped in Crimea significantly. Every vessel that calls an officially closed Crimean port risks putting its owner under international sanctions. That’s why the number of violating ships decreased over the years of occupation: while in 2014, flags of 32 countries were seen in Crimean ports, in 2019, the number stood at 6. Also dropping is the general number of foreign vessels in Crimean ports.

The sanctions made Crimean maritime exports and imports illegal and it rendered the whole port industry of occupied Crimea unnecessary for the economy. This means that Crimea is losing a major part of its economy, leading to further expenditures by Russia to sustain the territory it occupied.

Sanctions thwart the militarization of Crimea

The prospects to be sanctioned is one of the factors that stop many Russian enterprises from expanding their operations to Crimea or maintaining their production in the peninsula. This is important for resisting the absorption of Crimea into Russia overall and increasing Russia's expenditures, but it is especially important for thwarting the militarization of the peninsula that Russia is increasingly turning into a military base. Particularly, the report estimates that Russia invested up to 150 billion rubles ($1.25 billion) into its military base in Sevastopol, leading the experts to conclude that

"the main reason for the existence of occupied Crimea for Russia is to provide transit from the territory of Russia for everything the military base in Sevastopol needs."

Therefore, any sanctions that make it more difficult for Russia to develop its military make it more difficult for it to expand its military base that threatens not only Europe but the Middle East.

Particularly important for Russia in the occupied peninsula were the Crimean plants that could be used to bolster Russia's military production. Particularly, in 2018, Russia incorporated the Zaliv shipyard in Kerch and Morye shipyard in Feodosiya in the overall framework of military production, as a result of which several warships were built, namely - diving boat Vodolaz Kuzminykh, Karakurt small-size missile ships, experimental multi-role high-speed vessel of Project 03550 Sleming-2, and other ships for the Russian Navy.

In 2019, the US slapped sanctions on six Russian defense firms collaborating with the seized shipyards in Crimea. This led to the unplanned suspension of military production in Crimea - namely, in the Morye shipyard.

After the occupation as Russia seized all Ukrainian state-owned assets, the Leningrad Shipyard Pella became a “curator” and a “leaseholder” of the Feodosiya-based Ukrainian state-owned Morye Shipyard. The state of Russia leased the stolen factory to the Pella in fall 2016 until the end of 2020, and the Saint-Petersburg based Pella laid down a number of military ships at the Crimean shipyard.

However, under the threat of international sanctions, Pella decided to suspend the construction of the three missile corvettes of the Karakurt Project simultaneously in October 2019, a year before the lease term expires. It had to transport unfinished ship hulls along a more than 3,000-kilometer route from Crimean Feodisiya through the Azov Sea, along the rivers of Don and Volga up to Saint-Petersburg.

In 2020, Russia had for the first time assembled an entire warship at Zaliv, the Pavel Derzhavin сorvette, and is assembling four more corvettes. In May 2020, for the first time in the history of the Russian Navy, the construction of two Landing Helicopter Docks carrying 20 attack helicopters and 1000 marines was scheduled to begin at the seized Zaliv shipyard.

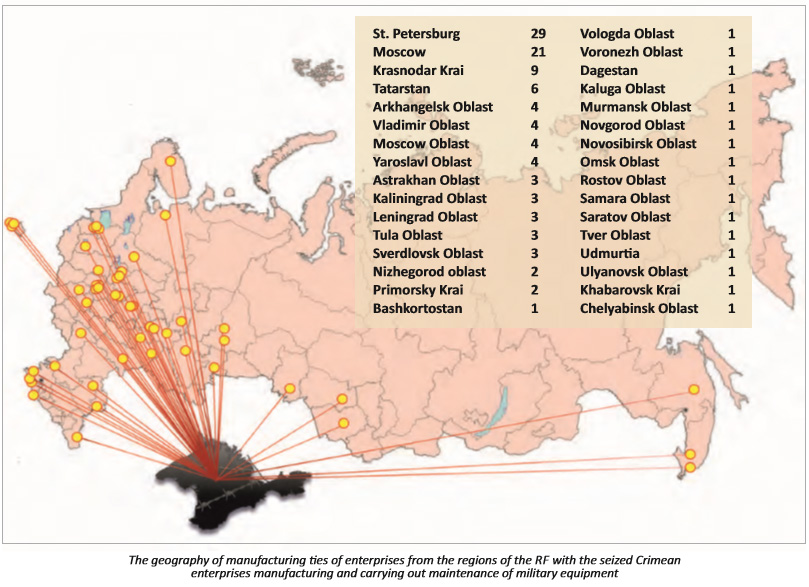

The construction of these amphibious assault ships will greatly enhance Russian military expansion in the Black Sea-Mediterranean region. As well, the construction of warships of this class will require production cooperation with hundreds of plants in Russia.

Sanctions should not only remain but be expanded

All the sanctions had clear causes and the Russian Federation hasn't even tried to get anything back to the status quo or undo any damage it had done to Ukraine. Neither had the Kremlin ever recognized the true nature of its actions, sticking to its propaganda narratives that only justify everything it has done instead.

Therefore, if some of the sanctions are eased or lifted without Russia fixing the issues, the Kremlin will see such a move as an appeasement of the aggressor; impunity will only escalate Russia's aggressive behavior.

As well, sanctions thwart the further integration of occupied Crimea into Russia, making it harder for the aggressor to sustain the territory it occupied and increasing overall expenditures on transport and infrastructure. As well, they undermine the economic sustainability of Crimea, forcing Russia to dole out subsidies to the region from its state budget.

Russia's economy further takes a toll from the indirect costs: it is estimated that international sanctions cost Russia 2-2.5% of its GDP in 2018.

Crucially, military-related sanctions can slow down Russia's military growth in Crimea, as well as create difficulties for the incorporation of Crimea's shipbuilding facilities in the Russian defense infrastructure. This is important for overall security in Europe, as well as to counter Russia's increased influence in the Black Sea and Mediterranean regions. The production of major warships with the help of seized shipyards in occupied Crimea will require the collaboration of hundreds of Russian enterprises and offers new opportunities for enacting sanctions.

At present, the Kremlin's political unwillingness to comply with international rules destroys the country's economy slowly but surely; sanctions have Russia, even if it is not clear at first sight.

But to obtain results, sanctions should be expanded, argue the authors of the report "The real impact of Crimean sanctions," and offer an updated Crimean sanctions package, arguing that Crimea has become a base for Russia's military expansion not only in mainland Ukraine but also more widely in the Black Sea-Mediterranean region.

Particularly, this sanctions package could include the following measures:

- synchronizing the sanctions lists of Ukraine, the EU member states, the USA, the Commonwealth of Nations that include Russia's legal entities operating on the occupied Crimean peninsula;

- imposing international sectoral sanctions on Russia's shipbuilding industry for collaboration on the construction and repair of Russia's warships and vessels at Ukrainian plants and design bureaus seized during the occupation of Crimea;

- imposing international sanctions on Russia's enterprises involved in the production, repair, and maintenance of military equipment at enterprises in occupied Crimea;

- imposing international sanctions on all owners and operators (managers) of vessels that called at ports of the occupied Crimean peninsula in 2014-2020;

- imposing international sanctions on Russian ports in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, namely Port Kavkaz, Rostov-on-Don, Temryuk, Azov, and Novorossiysk, for regular maritime transportation from these ports to the occupied Crimean peninsula.

Read also:

- Sanctions matter even if they won’t change Putin’s policies because ending them would lead to disasters

- Russia pushes to complete Nord Stream 2 challenging US sanctions

- Urging to reconsider Russia sanctions: peace at the cost of European integrity

- Pandemic adding to burdens sanctions have imposed on Moscow for seizing Crimea

- Company that brought “little green men” to Crimea violated EU sanctions for years

- NGOs to push for sanctions on 29 Crimea-based enterprises and their 60 Russian collaborators

- Sanctions matter even if they won’t change Putin’s policies because ending them would lead to disasters

- Britain urged towards Magnitsky-style sanctions against torturers of Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin

- What if Russia wins in Ukraine? Consequences of Hybrid War or Europe