Does the Hybrid War actually work? In the aftermath of the first round of the presidential election in Ukraine, that question has become more relevant than ever. Additionally, it triggers the need for new predictions for 2019 and beyond.

Basis for a prediction

During the last decades, NATO has been an active and leading contributor to peace and security on the international stage. In the process, NATO has demonstrated its doctrinal and technological basis for both present and future operations. It is based on an effective combination of two key pillars: cutting-edge weapons systems and platforms, and forces trained to work together seamlessly. The validity of small, but technological advanced capacities has been demonstrated (in scenarios of our own choosing).

The alliance has demonstrated its comprehensive approach to operations. This includes the parallel and synchronized use of both military and non-military means in order to influence, defeat, or stabilize an opponent.

At the same time, both the conduct of operations as well as debates triggered by them, has fully demonstrated our core values. These include respect for human dignity and human rights, freedom of religion, freedom of thought, freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, democracy, equality and the rule of law. Values we adhere to, uphold and protect, and consequently, are open for exploitation. The debates have simultaneously shown that NATO has grown wary of costly, complex and enduring operations.

We have basically “shown our cards while continuing playing with the same hand”.

On 27 February 2013 (barely one year before Russia started its military aggressions in Ukraine), General Valery Gerasimov, the current Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia, published his analysis of the last 10 years of conflicts. In the article “The value of science in prediction” (translated and analyzed by Mark Galeotti) he concluded, that:

- “The role of non-military means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness.”

- “Frontal engagements of large formations of forces at the strategic and operational level are gradually becoming a thing of the past. Long-distance, contactless actions against the enemy are becoming the main means of achieving combat and operational goals. The defeat of the enemy’s objects is conducted throughout the entire depth of his territory.”

- “The focus of applied methods of conflict has altered in the direction of the broad use of political, economic, informational, humanitarian, and other non-military measures — applied in coordination with the protest potential of the population.”

The Russian strategy for Ukraine is founded on the above observations. But not exclusively. It is also based on its analysis of both US and NATO military innovations, including the doctrinal and technological basis for its use of military power. Most importantly, the strategy has been adapted to the victim of its aggressions: Ukraine.

Hybrid War (or whatever you would like to call it)

Adapting to the temporarily military domination established by NATO, Russia has introduced a conflict design which allows it to avoid our strengths, while exploiting our weaknesses. It has wisely chosen to challenge the West on its own terms.

I have found the term “Hybrid War” descriptive. It implies a war of mixed character or composed of different elements. Due to the dramatic consequences of the combined use of both military and non-military means, war is most certainly the only accurate description of the ongoing aggressions.The hybrid war seeks to weaken and subdue. Physical destruction of the enemy is not its goal

Bohdan Yaremenko recently described “its totality” as one of the features of the hybrid war.

Targeting the economy, energy, politics, diplomacy, religion, the information space, cyber, internal security and more, the hybrid war is more radical than wars of the past. Not only because of its comprehensive approach and potentially devastating effects, but also due to our lack of effective strategy to counter the threat.

Conflict design

In accordance with the International Criminal Court, Russia instigated an international armed conflict between Ukraine and the Russian Federation not later than 26 February 2014. The legal definition of its aggressions in Eastern Ukraine is still being worked out (five years after its aggressions started). The preparations for the military aggressions, however, started years earlier.

Russia started employing non-military means against Ukraine means years before the armed aggressions started. It meddled in Ukrainian elections, supported pro-Russian political forces in Ukraine, established political and military influence, introduced treaties and bilateral agreements beneficial to Russia, ensured control over the Ukrainian energy supply, invested in the Ukrainian economy, secured the position of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine, engaged in a propaganda war against Ukraine, and more. Much more.

Sun Tzu’s explained the wisdom of avoiding the strength and striking the weakness of one’s enemy. The principle is equally applicable in the employment of both military and non-military means. It allows you to win all without fighting. The use of non-military means allows Russia to target and exploit core values of democracy.

If successfully employed, the victim doesn’t even recognize that it is under attack before the military means are being employed. More importantly, it undermines the military resilience of the victim. The Ukrainian Armed Forces were effectively dismantled during the period 2010-2014. Russian generals were at the head of Ukraine’s armed forces and security agencies. It was literally in ruins through

“… the mechanisms of foreign agents, the sale of troops, demoralization, criminal reduction of the military personnel, elimination of the logistics system, elimination of the training system.”

When hostilities finally broke out, the annexation of Crimea bore all the hallmarks of a well-planned and prepared military operation. Even the attempt to destabilize the eastern and southern part of Ukraine during the spring of 2014 had signs of previous planning due to the comprehensive and cross-sectoral Russian effort. The non-military means had consequently been actively employed many years before both Ukraine and the international community recognized the situation as an interstate conflict.The similarity between the Russian strategy and the Nazi German annexation of Austria and the occupation of Czechoslovakia is striking. As of today, the international community at the time chose dialogue in the face of several “hybrid de-escalations.”

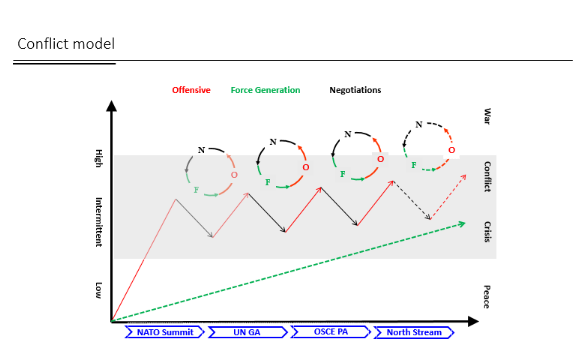

The military effort has followed several lines of operation. It allows for both escalation and de-escalation, followed by negotiations.

Russia has equally utilized the time for dialogue most effectively. It has rebuilt, trained and exercised its military forces, preparing for a military confrontation if required. The militarization of Crimea is a reflection of the Russian force build-up along the Russian/Ukrainian border. The Swedish Defence Research Agency has analyzed Russia’s Strategic-level Military Exercises from 2009 till 2017. The report concluded that Russia is Training for War. At the end of 2018, NATO published the report “VOSTOK 2018: Ten years of Russian strategic exercises and warfare preparation.”

“Nearly five years on from the initiation of hostilities against Ukraine and three years after the start of operations in Syria, Russian military forces continue to operate in both theatres, while also continuing or initiating operations (such as air and maritime patrols) in other regions. [ ] These developments suggest the need to reassess doubts about Russia’s ability to sustain military operations, including large-scale ones”.

The level of violence varies between intermittent and high intensity in order to remind Ukraine about the constant threat to its sovereignty. Both the build-up of Russian forces along its border as well as its regional capacity building supports the efforts. As a consequence, Ukraine is forced to prioritize its limited budget for the reestablishment of an effective security and defense sector. The Ukrainian authorities are effectively denied the opportunity to fulfill the expectations of both society as well as its strategic partners. The economic impact of the aggression on Ukraine is crucial to Russia’s attempt to destabilize Ukraine from within.

The Russian information campaign is a crucial part of the conflict design.

An effective information campaign helps rising expectations beyond what’s reasonably achievable while fuelling the anger and disappointment when the expectations are unfulfilled. Simultaneously, military and non-military means are being employed in order to ensure that the expectations remain beyond reach.Attacking schools, residential areas and civilians (etc.) exploits the West’s focus on humanitarian challenges.

Targeting the international perceptions of Ukraine and the domestic trust in the Ukrainian institutions follows the same logic. Attacking schools, residential areas and civilians (etc.) exploits the West’s focus on humanitarian challenges. Sabotaging reform processes would equally undermine the international support and destabilize Ukraine from within.

Exporting and exploiting corruption within the political system is an element of the same strategy. Corruption within the fields of politics, justice, security, and defense erodes the confidence required in order to stabilize Ukraine, ensure international support and attract foreign investments.

Russia has so far not used its full military potential. It has avoided a full-scale war.

The Russian strategy exploits the international community’s lack of strategic patience.

Time is an essential asset in view of conflicting national interests, shifting political focus, commitments, and alliances. The hybrid war doesn’t require a military victory; only the ability to outlast your opponents.

The most important aspect of the hybrid war seems, however, to be its hybrid aim and objective. After five years of Russian aggression, the international community is slowly awakening to the realization that Russia is attempting to undermine Western values and institutions. While Ukraine is an essential prize, Russia has global ambitions.

Does it work?

I am tempted to respond affirmatively to the question. The Ukrainian population is in the process of demonstrating its effectiveness.

Ukraine is no longer as united as it was six months ago. Sadly, the Russian aggressions united Ukraine in time of distress; while the Russian hybrid war over time has potentially succeeded in weakening it. Both president Poroshenko and Zelenskyy have called for national unity.

Ukraine's voters are blaming president Poroshenko for all the problems and unfulfilled promises. In accordance to recent polls, 68% of the voters supporting presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelensky will be casting their vote in protest of the situation in Ukraine.

Myroslav Marinovich, recently summarized the Russian efforts to destabilize Ukraine brilliantly when he pointed out that the Russian tactic:

“is to channel outrage of people in one direction and to make Putin’s enemy the enemy number 1 of the Ukrainians. This is a huge talent to do this and people bought it.”

In 2015, Lucy Sohryu published an article with the catching title “Teaching responsibility” in which she explained the political power and responsibility of both the president and the Ukrainian Parliament. The author pointed out that in a semi-presidential republic like Ukraine; the head of state enjoys larger than ceremonial powers, but does not actually control the executive branch outright. The President is responsible for things like national security and foreign policy. He is the guarantor of the Constitution and represents Ukraine abroad. Normally, he also exercises some control over his faction in the Rada (but nowhere near to the control Putin exercises over United Russia). And that’s it. The President of Ukraine “is not actually the head of the government’s executive branch. Or, for that matter, any other branch. The rest falls to the Rada. Nothing may be done till the Rada says it’s the law.”

There are of course several nuances to the above explanation.

Rostyslav Averchuk argues that the president of Ukraine has stronger constitutional powers than any other president does in countries with the same form of government. While formally he does not belong to the executive branch of powers, the “strong veto power alone enables the president to take an active part in the legislative process.” His actual power is, however, defined by whether he controls the majority in the parliament or not. Averchuk concluded, however, that

“the institutional restrictions on the presidential authority in Ukraine do seem to work. The powers and the influence of the president are weaker than they were under the former presidential-parliamentary model (1996-2006 and 2010-2014).”

What is he being blamed for?

In a survey conducted in November – December 2018, 82% of Ukrainians assessed the socio-economic situation in Ukraine as bad. The military conflict in Eastern Ukraine is the main concern (58%); closely followed by low wages and pensions (57%); increased tariffs for utilities (52%) and increased prices on basic goods (35.9%). In 2014, president Poroshenko promised to end the conflict within months after taking office.

The Russian use of military force caused the Ukrainian GDP to contract by 16% during 2013-2015. Inflation, exchange rates, credit rating, trade, foreign investments, and even taxation are still being affected by Russian aggression. North Stream 2, Russian sanctions, continued military operations in Donbas and the maritime blockade in the Sea of Azov are all designed to further erode the Ukrainian economy.The government has been unable to convey their many success stories. The great majority wouldn’t trust the message, nor the source or the news channel

In a poll published at the end of 2018, more than 60% of Ukrainians responded that they were not satisfied with how democracy has developed. Public trust in Ukrainian institutions and organizations are extremely limited. Institutions like the media, Security Service, National Police, State system of social protection, Public health system, National Anti-Corruption Bureau, State pension system, Prosecutor's Office, President, Prime Minister, Political parties, Cabinet of Ministers, Judicial system and Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine have all a huge negative trust/distrust balance (media being the “best” (minus 31%) and Verkhovna Rada the worst (minus 84,4%)).

As a consequence, the government has been unable to convey their many success stories. The great majority wouldn’t trust the message, nor the source or the news channel.

Russia has, of course, exploited the inherent distrust within Ukrainian society.

Ironically, Zelensky has used the very same undercurrents as the basis for his presidential campaign. He has tapped into the anger, frustration, and disappointment within the Ukrainian society, becoming a representative of the anti-establishment forces.

Most of its international partners have turned down Ukraine’s request for support of military systems and material. Struggling to fully rebound economically, Ukraine is being forced to prioritize the National Security and Defence Sector ahead of all other sectors.

Due to Russian aggression, the latter has been prioritized above all other commitments for the last five years. In spite of being priority no 1, it is still grossly underfunded. The Armed Forces have not been able to invest in high-end technology in the volume which as required. Nor has it been allowed to close some of its critical vulnerabilities. Imagine the budgetary situation within all other sectors if the National Security and Defence Sector is underfunded?

Lacking the budget, the government lacks the means to meet domestic and foreign reform expectations. As a consequence, the overwhelming majority of the population believe that the country continues to move in the wrong direction (68.3%). Nearly 2/3 of respondents in a recent survey indicated that radical changes are needed (63.7%).

Predictions for 2019

Five years after the Russian aggressions started, the Ukrainian population has every right to protest. The direct and indirect consequences of the Russian hybrid war have made life harder. Costs of living are up and a number of post-Maidan expectations remain unfulfilled.The fact that Russia carries the main responsibility for the present situation seems lost to some.

President Poroshenko is of course not without blame. In fairness, he shares the blame with his predecessors, past and present parliaments, as well as the other Ukrainian institutions who have resisted reforms and allowed corruption to continue unabated.

The Ukrainian election is, in many aspects, identical to the US election in 2016. In the same manner as the Americans decided not to vote for Hillary Clinton and ending up with Donald Trump as a consequence (as opposed to electing), Ukraine might very well end up with Volodymyr Zelensky as a president for the very same reason.

Ukraine seems to have decided to punish the incumbent president, electing populism and uncertainty while at (hybrid) war as a consequence. The “American choice” might, therefore, indicate that the present national unity will be under threat. Ukraine runs the very real risk of division and internal instability.

A vote of non-confidence for president Poroshenko (and in reality, the present parliament) is not the same as a vote of confidence for Zelensky. The future president and parliament will have limited room for manoeuvre. The great majority of the Ukrainian population expect Ukraine to continue its Western movement. Having picked someone who (on the face of it) represents a new political force, the expectations for reforms, fight against corruption and a higher living standard will, however, increase. Sadly, there are no quick fixes.

Russia’s attempt to gain control over Ukraine will continue in full. The Ukrainian economy will not miraculously rebound. Consequently, Ukraine does not have sufficient financial muscles to both build an effective Security and Defence Sector as well as fulfill its “social contract” with the population. The opening of North Stream 2 might, in fact, aggravate both the security and economic situation.

Additionally, in 2018 the conflict evolved into the maritime domain. The maritime blockade of the Ukrainian ports in the Sea of Azov has increased the financial burden on Ukraine.

Electing a new president doesn’t change the parliament. That comes later. There is, however, no reason to believe that the reform tempo will increase under the same parliamentarians with a different political affiliation. As we have seen elsewhere in Europe, it will take generations to eradicate corruption, oligarchism, and vested interests and reform the juridical system.

What’s going to happen after the presidential election?

The power to change Ukraine is vested in the parliament. Consequently, a new president will not be able to make any real impact on the present situation. Depending on his ability to control the block of "Servant of the People" faction and its future alliances, we shouldn’t expect to see any changes to the Ukrainian domestic or foreign policy before or after the parliamentarian election. The outcome of the presidential election is, however, an indication of an upcoming parliamentarian “tsunami”. New political blocks and alliances will emerge, potentially to the benefit of Russia. Or not.

Russian has been able to exploit the protest potential of the Ukrainian population. The hybrid war has enabled the rise of populism and wishful thinking, increasing Ukraine’s vulnerability for future protests, division of society and destabilization. According to some, Zelenskyy is attracting voters from both anti-establishment and pro-Russian forces as well as Ukrainian patriots. In spite of the inconsistency, the latter are dead-set on punishing Poroshenko for expectations not fulfilled.

Russia has, consequently, no reason to change the present conflict design before the parliamentarian election. I expect the military part of the conflict to remain low intensity, while Russia will intensify its attempt to influence minds and hearts in order to ensure a positive outcome in the next election.

After the parliamentary election?

Russia’s strategic aim and objectives for Ukraine will not change until Ukraine either falls or succeeds in building a strong economy and consequently, the Armed Forces required in order to defend the country, deter future aggression, and protect Ukraine’s national interests. Becoming a NATO member would be an immensely important milestone in this context.

The outcome of this election will, consequently, have influence on the future political, diplomatic and military posture of Russia.

If Russia fails to undermine the pro-Ukrainian and pro-reform forces within the parliament, it might change its strategy altogether. The build-up of Russian forces on Crimea and along the Ukrainian border has been ongoing relentlessly since 2014.

Oleksanrd Turchynov shows Russian military build up around Ukraine. Russia is preparing for war. #KSF2019 pic.twitter.com/Mjvxdkt7XC

— Orysia Lutsevych (@Orysiaua) April 11, 2019

In spite of the extremely impressive reestablishment and modernization of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the same period, Ukraine has unfortunately not been able to close all of its critical vulnerabilities. Being open for exploitation, one should expect Russia to utilize its military superiority within both the air and maritime domain.

Russia has been building the legal case for a humanitarian intervention since 2014.

Its key strategic documents have been updated accordingly. It has argued for the need for an international peacekeeping force (on terms unacceptable for both Ukraine and the international community). The effort has been supported by an extensive and far reaching information, diplomatic and political campaign. But most importantly, and as previously stated, Russia has been gradually building its military capability to execute an operation based on the “need” for a humanitarian intervention, but designed to break the back of the Ukrainian economy. The emergence of a Russian “Peacekeeping force” in Donbas, supported by a maritime embargo in the Black Sea and a no-fly-zone over parts of Ukraine, would have devastating impact on all sectors of Ukrainian economy.

Outcome

The predictions might be perceived as somewhat pessimistic. Admittingly, it is difficult to paint a positive outlook in the face of the Russian hybrid war.

But the one factor which truly makes a difference is the Ukrainian population. Having lived in Ukraine from 2014 until 2018 (and returning next year), nothing has impressed me more than the civil society’s democratic awareness, its contribution to the fight against Russian aggression and its assistance to Ukraine’s gradual transformation into a future member of both EU and NATO. I have observed a commitment and engagement I have never seen anywhere else in Europe.

When being asked about the situation and future development in Ukraine, I always respond: “When you say Ukraine, what do you mean? The country? It’s legally elected representatives? The Ukrainian institutions? Or the Ukrainian population. Depending on what you mean, the answers will be different!”

For a nation at (hybrid) war and at times, close to defaulting, I am truly impressed by the achievements so far. Ukraine has demonstrated a moral, motivation and resilience which I am sure, has surprised Russia.

I have faith in both Ukraine and Ukrainians.

Read also:

- The Kremlin’s hybrid arsenal – an annotated checklist

- This war won’t end while current Russian authorities hold power in the Kremlin – Horbulin

- Rules for peacetime don’t work when you’re at war for national survival

- How it all happened: The Hybrid War in Eastern Ukraine

- How states can get real about Russian cyber attacks: Estonia, the UK, and Poland explain