- Moreover, in 1991, not only Ukrainians but also Russians and other nationalities — 83% of Donbas inhabitants — voted for Ukrainian independence.

- Self-declared separatist republics emerged exactly in Donbas some 23 years later, thanks to Russian backing.

The demographic portrait of the region: how Russian propaganda used it

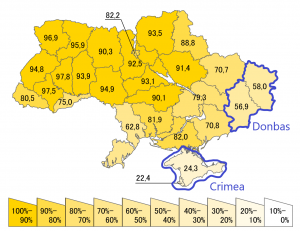

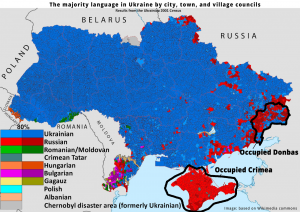

The ethnicity map of Ukraine suggests that Putin had a reason to target the territories of Donbas and Crimea. These are the regions with the smallest percentage of Ukrainians in the country.

Crimea was the only Ukrainian region where Ukrainians were the minority. The proportion of Russians, Ukrainians, and Crimean Tatars in Crimea was around 5:2:1. In the case of Donbas, Ukrainians were 1.5 times more numerous than Russians. However, both in Donbas and Crimea, Russian was the most common native language (in the Donbas, due to a large part of Russian-speaking Ukrainians). Putin used the commonality of the Russian language in south-eastern Ukraine as the main justification for a Russian invasion. The line separating Russian-occupied and Ukrainian-controlled territory runs across territories where the Russian language dominates. And occupied Crimea is predominantly Russian-speaking.

In no way do these demographics justify Putin's aggression or annexation, but they explain why the Kremlin indeed had a part of the local population to rely on. Russian propaganda has claimed that Donbas and other south-eastern oblasts of Ukraine were simply Russia’s regions artificially appended to Ukraine. This, in particular, was stated in the separatist project of “Novorossiya” for Ukraine in 2014. According to it, all south-eastern Ukraine was to belong to Russia or to participate in a so-called confederation of people’s republics.

Read more: 5 facts about “Novorossiya” you won’t learn in a Russian history class

Putin and pro-Russian separatists claimed such a position was historically justified because these regions were conquered, colonized and built up by the Russian Empire. However, this is not a sufficient argument even for Donbas:

Though not historically justified, demographically “Novorossiya” project was comprised of the oblasts of south-eastern Ukraine which voted for pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych in 2004 and, similarly, in 2010. (In 2014 Viktor Yanukovych was removed from the presidency by a parliamentary vote in the consequence of the Revolution of Dignity). Also, a significant part of people in these regions was Russian-speaking, though Ukrainians still constituted a strong majority — 56-82% depending on the oblast.

On the other hand, many Ukrainian historians and even some politicians, like Yevhen Nyshchuk, the Minister of Culture of Ukraine have portrayed the cities of the south of Ukraine and Donbas as imported from Russia during Soviet times. This is yet another manipulated historical fact. Hennadiy Yefimenko, a researcher of resettlement and deportations on the territory of Soviet Ukraine during the interwar period, tells that resettlements from Russia to Ukraine were not so decisive in forming the population of these areas. Overall, 138,000 of people were resettled from Russia - around 3% of the Ukrainian population at that time. More common, however, were forced resettlements inside Ukraine. In the case of Donbas, more people were resettled from the northern Chernihiv Oblast to Donbas than from the whole of Russia.

Neither the portrait of Donbas as initially Russian (Novorossia) nor the portrait of its inhabitants as imported from Russia is fully right, though the formation of the local population of the region was indeed very complex and to a large extent artificial. This last thing created favorable conditions for vulnerability and instability in the region.

Historical insights

Prior to the 18th century, the territory of contemporary Donbas was nearly depopulated. It was a frontier territory between Ukrainian Kozaks (independent warriors) and nomadic peoples. This land was called the Wild Fields (Dyke Pole in Ukrainian). The Donbas is the youngest region of Ukraine because its systematic colonization began only in 18th century. First, it was colonized by Ukrainian Kozaks who created there the Kalmius palanka (Kalmius district) which existed between 1739–1775. After the liquidation of the Kozaks’ autonomy by Russian Empire, those territories were distributed among different nobles and in 1802 The Yekaterinoslav Governorate was created there. This Governorate, according to the first census of the Russian empire in 1897, was populated on 68.9% by Ukrainians and 17.3% by Russians. This fully ruins the propagandist myth that Donbas was ethnically Russian during the Russian empire.

Up to 1870s, the region was still mainly agricultural where most peasants were Ukrainians.

In the 1840s, the mining of Donbas coal was still unprofitable because of bad organization of mining and transportation. At the same time, in the ports of Azov and Black sea, European coal was sold to the Russian Empire at a cheaper price. Only in 1886, the Katerynoslav railway was built in Donbas and it changed the situation entirely. Rapid development began in the region then, and whole new cities were built around new mines among empty steppes in some 3-4 years. The mines and cities required many workers, which lead to demographic changes regarding the social status of inhabitants but not their ethnicity. Most of the industrial workers were former Ukrainian peasants who couldn’t find free land and had to move to new industrial and miner’s workplaces. Also, Russians, Belarusians, Greeks, and other nationalities worked in the region. But even summed up, their number was smaller than the number of Ukrainians.

On the other hand, when moving to Donbas, Ukrainian peasants faced many social problems which made them lose their national identity. First of all, it was language. At first, the industry was “speaking” German and English because of the western capital which was a driver of local industrial development. However, since the 1890s, Russians took more and more ruling positions. In general, it was common that Russians preferred living in industrial cities while Ukrainians wanted to remain in their villages as long as possible. Subsequently, despite prevailing by number, Ukrainians remained on the bottom of the social hierarchy of industrial region, moving there not because of their will but because of the conditions.

As Maksym Vihrov, Ukrainian researcher of Donbas writes, when Ukrainians came to Donbas, they had to learn Russian right on their new workplace since the end of 19th century and this remained the case throughout the 20th century.

According to Tetiana Portnova, who also investigated the resettlement to Donbas, peasants were heavily affected by the gray industrial cities of that time, without trees, with large barracks for workers to live in, full of dust. This sharply contrasted with the places and social conditions where Ukrainian workers used to live before. It was hard for peasants even to get used to such simple things like daily registration at the workplace and work in accordance with a particular shift round the clock, sometimes at nighttime. People didn’t know each other in the giant factory, the staff turnover was extremely high.

All these conditions created a kind of a melting pot, where people had to forget who they were before and either become a new class of workers or return back to other regions.

In the 1920-1930s, during Stalin’s policy of industrialization, this melting pot was warmed up by regular official referrals to work in Donbas from all regions of Ukraine and also outside of Ukraine. Also, people were forced out from their homelands by collectivization (creation of common farms) and Holodomor. Former prisoners preferred to take cover in the anthill of industrial giants. Generally, the migrants, despite mainly Ukrainians, couldn’t fully reproduce their own culture and even language in the social conditions of Donbas under the pressure of Russian elites and Soviet propaganda. New settlers of Donbas were usually dissimilated in the mass of Soviet people in the second and third generation, and the Russian language became dominating.

Simultaneously to Holodomor, the official Russification of the region began in the early 1930s when a large flow of workers was coming to Donbas. Maksym Vihrov writes about an interesting example of the magazine “Literary Donbas” which had been published in Ukrainian till 1930. The editor-in-chief Vasyl Haivoronskyi remembers that the team was accused as betrayers and the magazine was closed in 1930. However, a few months later a new “Literary Donbas” emerged, but this time in Russian. This one paved the way for some local Russian writers.

Later, in the 1950s-1960s, Ukrainian writers rebounded because of the softened official policy. Many Ukrainian writers of that period were originally from Donbas and some, like Vasyl Stus, were still living and writing in Donbas. It’s incredible that prior to 1971, when the government of Ukrainian SSR again turned pro-Russian, Donbas had more Ukrainian schools than after Ukraine's independence in 1991.

Altogether these conditions led to 56% of Donbas inhabitants still self-identifying as Ukrainians but overwhelmingly speaking Russian in 2001 against 68% Ukrainian-speakers in Donbas in 1897.

Yaroslav Polishchyk also mentions in his research one prominent example of Donbas people’ self-identification during the census of 2001. Many inhabitants of the region didn’t want to choose their nationality between Ukrainians (who were portrayed at Soviet times as inferior peasants) or Russians (who dominated and showed intolerance to others) and preferred to identify themselves as Soviet, though it wasn’t one of the many possible answers in the poll.

The same researcher writes, that “millstones of Russification, which were set during the Soviet times, continued circling in the age of Ukrainian Independence.” After 1991, the central government didn’t pay attention to the language policy in the region while local elites secured Russian in education and discouraged the use of Ukrainian. Except for 2 lessons of Ukrainian per week to fulfill official requirements, in most of the schools, Russian was de-facto the language of instruction during the times of Ukrainian Independence. This was the case even with state schools. For example, Luhansk had only three schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction — a nutshell for a city with 407,000 of inhabitants.

The first metaphor of Donbas in 1860-1914: hard physical labor in the steppes

The first metaphor was formed back in the second half of the 19th century. Fear and abhorrence were the main attributes of the region of that time. They were related to the unnaturally rapid speed of the development of the region ruled by the flows of the western capital since the 1860s. 95% of mines in 1914 were owned by foreigners from western countries. The price for the rapid economic development of the Russian empire was natural and beautiful steppes fully occupied by mines, destroyed by new cities full of hard work of thousands of people. This work was accompanied by typical for that time tensions between workers and owners. All this emerged in some 30-40 years.

On the one hand, the region was compared with the American frontier, the Wild West, which was colonized steadily from the neighbor lands where cities emerged on the empty land. New cities in Donbas were attractive because of electricity, modern technologies and promising speed of the development. From the very beginning, the region was torn from the inside between promising industrial and technological development and improper conditions of life.

The colonization and development of Donbas weren’t accompanied by the idealistic image of a cowboy but by the capital and mine. Due to rapidness of the developments, cities of the 19th century were lacking proper infrastructure and giant villages around the mines were common. In the process of quasi-urbanization city-scale was reached but not always with proper functions and level of life. The Italian historian Luidzhi Villary, while visiting Yuzivka (current Donetsk) in 1905, compared the city with “the gloomy views of the suburbs of southern London” because of the dirty streets, big factories and uniform buildings for workers. Metallurgical plants of that time caused mixed feelings of viewers. On the one hand, people were impressed by the power and scale of technologies. On the other — human was eliminated and subjected to these technologies and this was terrifying.

In that first period represented in the first metaphor, the region broke away with the past and natural steppes. Because the industrial cities were created on the empty lands from nothing, they were ahead of time and fully embodied the idea of monocities subjected to certain single industry where life was planned rationally and fully optimized, albeit this had negative consequences on social life and made people fully vulnerable to the government and industry of their city, controlled by local elites.

“In the story "Old Yuzovka", the Soviet writer Ilya Gonimov attributed to John Hughes the words that he allegedly said about the status of the city of Yuzovka: ‘This is not Russia. This is a factory!’. Despite the fact that this plot is similar to an artistic fabrication, it is repeatedly reproduced in academic texts, as described in the story, the situation is quite plausible” (the book “Work, exhaustion and success: Industrial Monocities of Donbas”).

The social and municipal issues, which normally were under the control of municipality, in Donbas where usually managed by the factory.

The second metaphor of Donbas in Soviet times: heroic labor in the heart of USSR

This second metaphor associated Donbas with Soviet industrialization and heroic labor. A hope of the human control over nature and changing it for better conditions was the driver of this period. The fear of dark and inconvenient cities around the mines was overcome by relying on technologies and creating the giant artificial world of agglomerations, channels, parks, and gardens.

From the very birth of the Soviet Union, propaganda portrayed Donbas as the heart of Russia and the heart of USSR — the most developed and important region in the country. It was indeed the most developed in terms of urbanization rate, for example, which from 1928 to 1938 rose from 29% to 74% and became the highest in the entire Soviet Union.

After the creation of the Soviet Union and especially during Stalin’s industrialization between 1918 and 1939, the mining of coal in Ukraine rose tenfold and almost all of it was mined in Donbas. This period was the most important for the region because it created hopes to which Donbas is still bound. In the 1920s the aestheticization of mines and heaps in literature and photography started for the first time and accompanied Donbas till the end of Soviet times.

According to Tetiana Portnova, who describes these transformations, the factory is no more the place of coercion, but the place of devoted work; the machine is no more subordinating the worker but becomes his governable instrument; a factory horn is not a symbol of coercion but a peculiar music of a new industrial society.

After the Second World War, the policy of beautification of the region began. Artificial forests and gardens were planted in the 1950s and later, as well as artificial lakes and channels made.

Resorts were established in the 1950s on the coast of the Azov Sea to provide a comfortable vacation for workers of Donbas. The region had to serve as an exemplary paradise for workers. The cult of the miner as a kind of elite worker was established and it was indeed mirrored in the size of salaries and better living conditions. Not all workers could enjoy personal car but some of them did.

As Volodymyr Kulikov and Iryna Sclokina write in the introduction to the book “Work, exhaustion and success: Industrial Monocities of Donbas” the life of workers in Donbas was ambivalent. The factory indeed cared for their living and provision of goods. At the same time, the factory created strong local paternalism which controlled the life of the city and even the private life of the worker.

However, the propagandist image not aways corresponded to reality. The best example is the comparison of two letters from 1949 which Tetiana Portnova provides in the mentioned book. The letters were written to those prisoners of the Third Reich who remained in Germany after the war. The first one was the letter written under the compulsion of propagandists:

And in stores - a full bowl of what you want and how you want, both products and manufactured goods. Shelves are loaded with various goods and, moreover, at affordable prices. Prices are decreasing each year, and wages are increasing, on the contrary.

And this one was the real letter written by the worker Mr. Biankin from Stalino (now Donetsk) confiscated by censorship:

Now I work in Stalino in the mine. We live as free people, but such freedom is worse than bondage. The payment is so small that it’s even not enough for a meal, and you will not earn anywhere on the side. I saw myself how many companions have already passed away — the picture is terrible. So many guys have run away, many are being convicted for theft. I absolutely do not have a conscience now, I can pull out bread out of someone’s hand, and I do not need anything else. How many of us here are such? What times have come? I hate everyone and people are afraid of me.

In the 1960s, the conditions in the region improved but after the 1970s, the investments decreased and the divergence between the image of the “elite” Soviet region and reality had again widened.

Inna Levchenko writes that Donbas inhabitants accepted two distinct cultural models simultaneously because of this second metaphor. On the one side, there was an image of a special region which deserves the highest level of living conditions among others. On the other side, the decline of coal industries which began in the 1970s and continued all the time till now created a feeling of injustice or, at least, anger towards the wrong governors, either in Moscow or in Kyiv.

The third metaphor of Donbas after 1991: existential emptiness

Finally, the third, the last metaphor that becomes prominent in our time, denies the previous and treats Donbas as a zone of complete crisis, dehumanization, and existential emptiness. As the Ukrainian contemporary poetess Lyubov Yakymchuk writes in her verses, contemporary Donbas is similar to the decomposing human body. People become disillusioned from previous hope: artificial channels and heaps turn out to ecological catastrophe and the region loses its economic importance. Last but not least, the war separates and destroys it.

The economic sign of this decay emerged already in 1976 when the peak of the coal mining was reached. The downfall of the next three decades was similarly rapid as the rise of Donbas one hundred years before. Today, the mining of coal in Ukraine is 3 times smaller in scale than in 1976. The reason for the downfall was the growing role of oil, gas and nuclear power as well as the breakup of the Soviet Union which resulted in the breakage of old economic ties. As the economy of the region depended on local industries and mines, these economic changes had heavy consequences and were depicted in the modern self-perception of the region, mirrored also in Ukrainian literature.

Serhiy Zhadan, a Ukrainian poet born in Luhansk Oblast was among the first who described the new existential emptiness of the region in his verse “The mushrooms of Donbas” (2007), where he depicts the total despondency in old ethos and portrays the current emptiness which can be filled by anything. In 2010 he wrote a novel “Voroshilovgrad”, which describes life in Donbas in total uncertainty and insecurity where business and mafia are bound together. It was named the book of the decade by BBC. The film based on the novel, The Wild Fields (“Dyke Pole” in Ukrainian) was directed in 2018. The trailer of the film perfectly transmits the spirit of the novel and the region, even if it is a bit exaggerated.

As Yaroslav Polishchyk writes in his research analyzing other Ukrainian writers from Donbas region, particularly Oleksiy Chupa and Volodymyr Rafayenko,

both writers reflect the existential loneliness and helplessness of each of the characters. Insecurity, uncertainty, and unpredictability, which they are constantly experiencing, are not only consciously, but also intuitively felt. After all, they live quite close to each other, even under one roof, but these people remain completely alien and can’t find a common language...

... At the same time, they [authors — e.d.] produce the corresponding, in their opinion, stylistics: dry, laconic, coarse, with elements of naturalism way of writing suits to the hard realities...

... Donetsk discourse of unregulated power, violence, tough guys, on the one hand, and obedience, humiliation, and silence, on the other, has already become a sad tradition.

When the crisis of the Soviet identity revealed itself, the new emptiness wasn’t filled by Ukrainian identity and Donbas, in the opinion of American political scientist Roman Shporliuk, remained one of those regions of the former Soviet Union where “one is enticed to call them the luddites of the post-communist era.”

Several important facts from the time of Ukrainian Independence illustrate faults in the regional state policy that prolonged the feeling of Soviet nostalgia and described Luddism.

The first important thing is the strikes of Donbas miners that began in 1989 as the answer to the decline of the local economy. Among other things, the miners supported in their strikes the independence of Ukraine which was mirrored later in the results of the national referendum for Ukrainian independence in Donbas.

However, the reasons for this support and affirmative voting were not ethnically or democratically driven, but economically and socially.

Accordingly to the miners’ requirements in 1990, they wanted to transfer financial accounting and payments from the level of Moscow to Kyiv and further regionalization of the economy in order to get more autonomy. Their strikes continued after the proclamation of Ukrainian Independence. Particularly, in 1993 one of the requirements was the autonomy of Donbas, still in hope of economic profits because of that. In 1996 miners who participated in the strike were heavily beaten by state police.

Generally, the state didn’t respond to the demands of miners by effective changes in the economy. Yet, the important thing, according to the research of Marta Sudenna-Skrukva, is that the strike movement was appropriated by newly emerged Donbas oligarchs in 1990s. The conditions of work and life among miners only got worse during the 1990s which created strong distrust towards Kyiv. From the end of the 1980s to the mid-1990s, the number of workers employed in mines declined from 1 million to 500,000, as an example of economic decline.

The social and class identity was more important for Donbas inhabitants than their ethnicity, nationality or language and the belonging to Ukraine wasn’t valuable as such. As the historian Andreas Vitkovskiy writes, the independence of Ukraine was the result of a tactical union of 3 powers: national elites, party nomenclature of the Ukrainian SSR which wanted to hold power and miners of Donbas who hoped that exit from the Soviet Union will save the coal industry. When it became clear that independence doesn’t give any guarantees of the immediate economic growth of mining industry, inner tensions took place.

Donbas oligarchs interested in profits could solve the economic problems to a certain extent. They contributed to the organization of exports of steel and local inhabitants acquired at least some semblance of stability together with sharp social stratification and inequality. Simultaneously, Donbas oligarchs were receiving support from the state in a form of subsidies for coal. Cheap coal made it possible to acquire giant profits from the export of steel by market price.

In spite of state subsidies for the coal industry, local elites were portraying Donbas in opposition to Kyiv, scaring local people by forced Ukrainization. The example of this pro-Russian malice against Kyiv in 2000s, especially after the victory of pro-European president Viktor Yushchenko is the case of Serhiy Melnychuk, a student from Luhansk, who in 2006 protected in the court his right to study in the Luhansk university in Ukrainian (otherwise it wasn’t possible to achieve adherence to his constitutional right). However, the student was heavily beaten during TV live by the local deputy Arsen Klinchaev and hospitalized. It was the same Arsen Klinchaev who raised the Russian flag over the Luhansk state administration on 1 March 2014.

During 1991-2014, the state didn’t care about implementing language laws. There were no sanctions for the use of Russian in the official documents, which also happened from time to time. State policies to incorporate the region in the Ukrainian language and cultural domains were absent. This explains why 56% of ethnic Ukrainians in the region (according to the census) didn’t have a voice and representation while the oligarchs and local elites were becoming more and more daring and even allowed themselves to beat their own citizens with impunity.

This also is one of the reasons why the existential emptiness remains just that, an emptiness.

It was also the case that only suboptimal candidates of parties alternative to the pro-Russian elites remained in the region and local elites had many real reasons to accuse pro-Ukrainian parties of wrongdoings. Among the most recent examples was the “symbolic assault” on the Luhansk state administration on 23 February 2014 by members of UDAR party armed with plywood shields and other Euromaidan-looking stuff. The assault didn’t lead to any real positive consequences. However, local pro-Russian and Russian media received the image of aggressive "banderites" who come to Luhansk to kill for the Russian language; local elites could once more show that they’re simply the best among inadequate Kyiv parties.

Read also:

- 12 facts about the Donbas that you should know

- Moscow’s integration of Donbas from below–via Russian regions–accelerates

- A businessman, nurse & food technologist: stories of three civilian hostages in occupied Donbas

- Moscow increasingly acknowledges it controls Donbas regimes, Kirillova reports

- How the UNR Army liberated the Donbas in 1918

- A warning sign in the Donbas: Moscow replacing local people with Russians

- The story of Alina, 23-years-old volunteer at the front line in the Donbas: #Being20