On 20 September 2017, at the United Nation's General Assembly (UNGA), Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko called for the deployment of a UN-led peacekeeping mission to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine that would "facilitate restoration of Ukrainian sovereignty and not freeze the conflict" in Donbas.

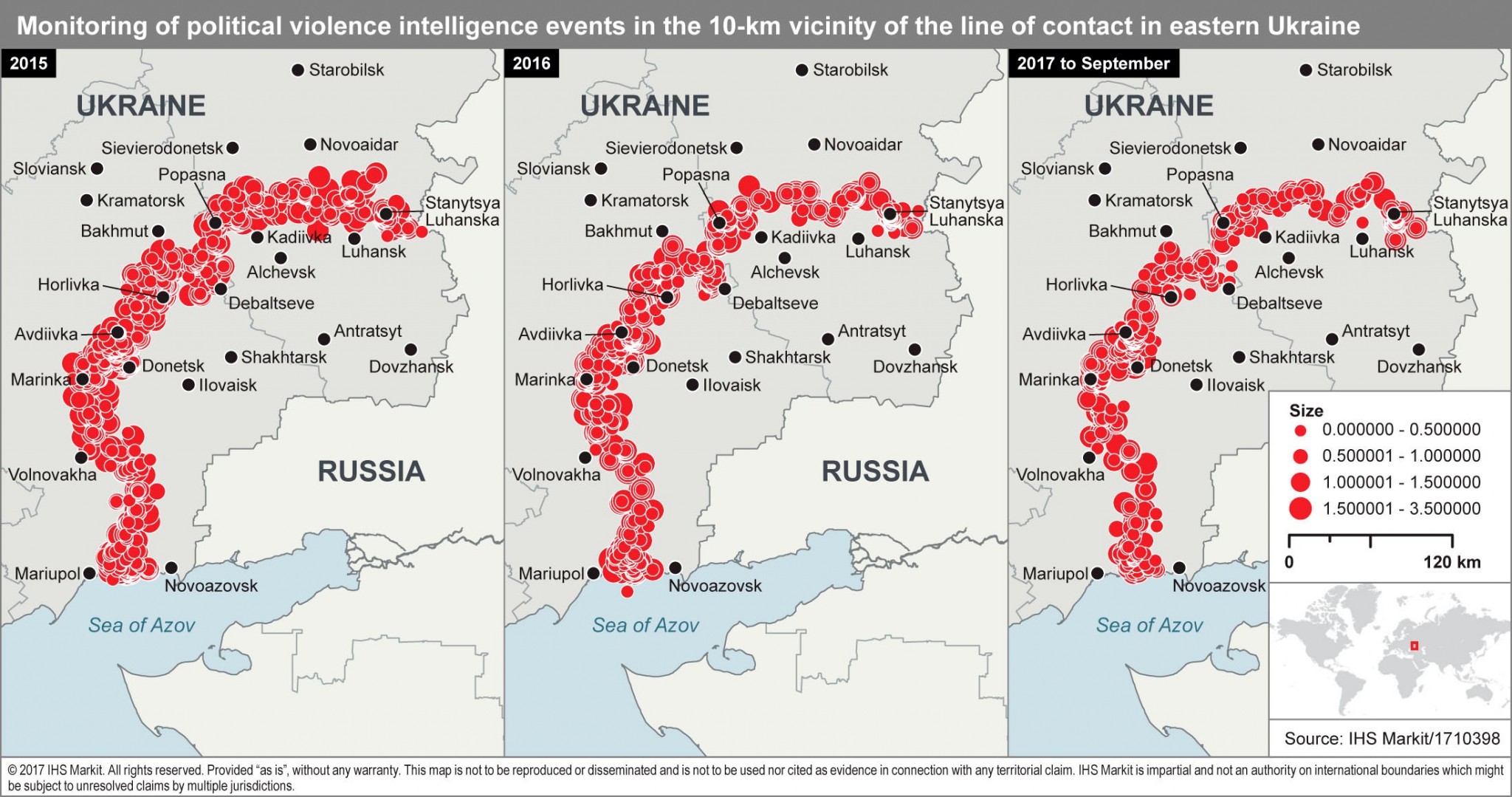

Poroshenko's statement was aimed at reviving the initiative on the peacekeeping mission to Donbas, the areas of armed conflict in eastern Ukraine since April 2014, which have been in a stalemate since early 2015. Although the conflict in Donetsk and Luhansk regions geographically stabilized in February 2015 along the line of contact (LoC) between the Ukrainian government forces and the pro-Russian separatist militias, there are continued outbreaks of localized fighting and a fluctuating rate of daily ceasefire violations along the LoC.

Ukraine has been calling for the deployment of peacekeepers in Donbas since early 2015, but Russia and the separatist entities in Donbas have opposed this initiative. However, Moscow's tone changed earlier this month: on 5 September 2017 Russian President Vladimir Putin called for a UN peacekeeping mission to be deployed in Donbas. The same day, Russia submitted to the UN Security Council its draft resolution authorizing the deployment. This triggered a counter-proposal by Ukraine on the following day.

Russian proposal

The Russian government, which views the conflict in Donbas as an internal Ukrainian conflict or a civil war, and does not acknowledge Russia as a party to the conflict, now proposes the adoption of a UN mandate for a six-month peacekeeping mission. The mission would be peace-keeping, rather than peace enforcement, authorized to use force only in self-defence, meaning that it would only be equipped with light weapons. Russia stipulates the following conditions in its proposal:

- The peacekeeping mission, rather than the Ukrainian government, would be responsible for the security of the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (OSCE SMM);

- The peacekeeping mission would operate only along the LoC between Ukrainian government forces and the separatist militias of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People's Republic (LNR);

- Any decision on the peacekeepers' deployment must be coordinated with the leadership of "DNR" and "LNR"; and

- Both Ukraine and the separatist entities in Donbas must withdraw heavy weapons from the LoC, widening the distance between the respective front lines.

The OSCE SMM, consisting of nearly 600 unarmed observers with the role of monitoring the security situation in eastern Ukraine, has been deployed in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine since March 2014. Its mandate was further expanded geographically to monitor the implementation of both the Minsk ceasefire agreement of September 2014 and Minsk II ceasefire agreement of February 2015. The SMM reports, on almost a daily basis, obstructions to its mandate, such as restrictions of freedom of movement or violence and direct threats against SMM representatives, mostly by separatist militias in the "LNR" and "DNR." In the first six months of 2017, the OSCE SMM reported 480 such incidents, 75% of which occurred in the areas controlled by the "DNR" and "LNR."

For instance, in April 2017, an OSCE SMM vehicle was hit with an improvised explosive device (IED) as two armored vehicles carrying six SMM representatives were driving on a secondary road near Pryshyb, Luhansk region, in the "LNR"-controlled territory. A US citizen working as a paramedic died and two monitors were wounded. Under the terms of the Minsk ceasefire agreement, signed on 19 September 2014 between Russia, Ukraine, "LNR" and "DNR," all sides committed to the cessation of laying of mines and IEDs as well as the removal of all existing mines. After the April 2017 explosion, the OSCE Mission on Ukraine changed its operating procedures, limiting its observer patrols to paved roads.

Ukraine insists on a broader mandate and Russian exclusion

In its own draft proposal, Ukraine stipulated several conditions to the UN Security Council, which significantly differ from the Russian proposal. Ukraine demands that Russia, which Kiev views as a party to the conflict, which provides political, financial and material assistance to the "DNR" and "LNR" separatist militias, is excluded from participation in any peacekeeping mission. Ukraine also insists that "DNR" and "LNR" are not parties to the political coordination on the deployment. In September 2017, both separatist entities, which had previously strongly opposed any peacekeeping mission's deployment, agreed to the Russian proposal.

The key disagreement on the proposal is the geographical mandate of the peacekeeping mission. Although Russia wants it limited to the LOC, Ukraine is seeking a deployment covering the entire conflict zone, including the 425-km long stretch of the Russo-Ukrainian border, currently controlled by the breakaway "DNR" and "LNR." Citing credible evidence, Ukraine claims that this stretch of the border is used by Russia to supply the Donbas separatist entities with weapons, materials and military personnel.

Outlook and implications

If the differences between the two proposals are overcome, which currently appears unlikely, preparation for deployment of a peacekeeping mission in Donbas would take six to nine months. Such a deployment would be likely to substantially decrease the number of shelling incidents across the LoC, especially near Mariupol, Donetsk, Horlivka, and Luhansk, reducing death and injury and civil war risks in the region. However, as Russia and Ukraine are very likely to reject aspects of the other's proposals and insist on their own conditions, a UN peacekeeping mission is unlikely to be sent to Donbas within the next 12 months.

IHS Markit assesses that the negotiations on the peacekeeping mission are most likely to continue in the one-year outlook, and no deployment will take place, with the armed conflict to continue in its current form.

Russia will seek to use the failure to reach an agreement as evidence of the Ukrainian government's intransigence, claiming that it is blocking a political solution. Although Russia would, under diplomatic pressure, be likely to agree to expand the geographical mandate of the mission to additional areas under the control of "DNR" and "LNR," it would still be likely to insist the mission's exclusion zone from the Ukraine-Russia border.

Russian agreement to a UN mission would likely also be conditional on Russian participation. This would likely be unacceptable to Ukraine, on the grounds of alleged Russian military connivance with separatist militias, and the expected consequence is that it would freeze the conflict, as it has in conflicts in Moldova or Georgia in the early 1990s, but would prevent a peaceful resolution.

In the longer run, such a scenario would lead to further distancing between the breakaway "DNR" and "LNR" with the rest of Ukraine. "DNR" and "LNR" would likely evolve as de-facto Russian protectorates, politically and economically linked to Russia and increasingly separated from the rest of Ukraine. This would prevent any Ukrainian aspiration to re-integration of Donbas. Failure to regain sovereignty over Ukrainian territory in Donbas would further restrict any Kyiv plans to progress on the road to potential EU or NATO membership. It would be a potential game-changer were the US and the West to apply sufficient pressure on Ukraine, which depends on funding from its Western sponsors and international financial institutions, to make concessions.

Read also:

- “Zapad-2017”: Russian sabre rattling towards eastern Europe

- Ukrainian President repeats call for peacekeepers to Donbas at UN Security Council

- Putin’s “peacekeepers” — a ploy to legitimize the Donbas “republics”

- Putin suddenly wants armed peacekeepers in Donbas. Why now? What for?

- Putin’s perfect trap for Ukraine

- “Russia tries to exchange peace in Ukraine for Ukraine’s freedom” – President Poroshenko at UN