On the “Novaya Versiya” portal today, Temur Kozayev reports that Putin has given his approval to a call from Vice Prime Minister Aleksandr Khloponin to create a state corporation for such explorations on the base of the Rosgeologiya state company which currently exists.

“The goal of the reforms,” the journalist says, “is to secure the independence of the country in geological exploration,” something that sanctions, the opening of the Arctic, and the contract with China make a first order necessity. But it is unclear whether this step will work or whether it will simply become another paper reorganization.

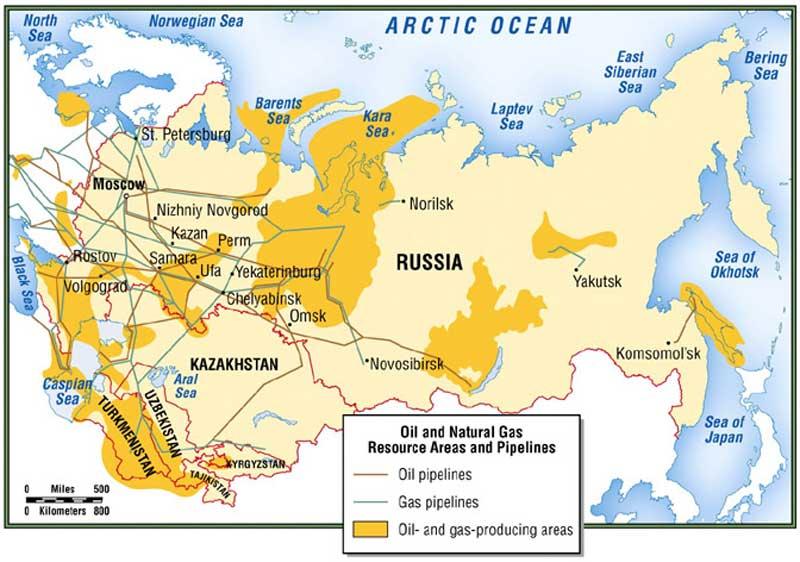

Academician Aleksey Kontorovich, head of the Institute of Oil and Gas Geology and Geophysics at the Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences, says there is no time to waste: Russian production of oil will begin to decline in five to ten years, and gas production may decline as well in the future unless new fields are discovered.

Failure to conduct such explorations over the last 20 years, Ivan Nesterov, the director of the West Siberian Oil Geology Institute, says, have cost the country an enormous sum of money, largely because the government has not been willing to commit the funds needed to explore for new sources as it exhausts old one and to do the kind of basic mapping work required.

In Western countries, all the territory has been mapped, but only 40 percent of Russia as a whole and much less in particular regions has been, with the average share of the territory now on accurate 1:50,000 maps being about 20 percent. And in some major areas, geologists haven’t even been allowed to go at all, such as the Taymyr peninsula.

Foreign exploration companies had been involved, but they are now leaving. As a result, Kozayev says, Russia must develop its own capacity in this area as a matter of national security. That will require an enormous investment, something Moscow could make if the money did not drain off in corruption.

The Khloponin proposal that Putin has now approved would put the state at the center of this “import substitution” effort, but the leaders of many major Russian oil and gas concerns do not think that is the way to go. Instead, they argue that the government should help them do the job. Consequently, Putin’s approval of the idea is unlikely to be the end of the story.

But given the withdrawal of Western firms and the commitments Moscow has made to China, the Russian government may feel it has no other choice than to try to boost an exploration organization that in the years since the end of the USSR, it has given remarkably little support. And if it does not, then Russian production of oil, gas and other natural resources will fall further and faster in the future than many are now projecting.