Moscow commentator Andrey Malgin delivers a warning that no one should ignore: Vladimir Putin, he argues, “will use Western values like direct democracy (referenda), freedom of speech and assembly and all the rest for the destruction of the West and these things which are its values.”

(Image: kasparov.ru)

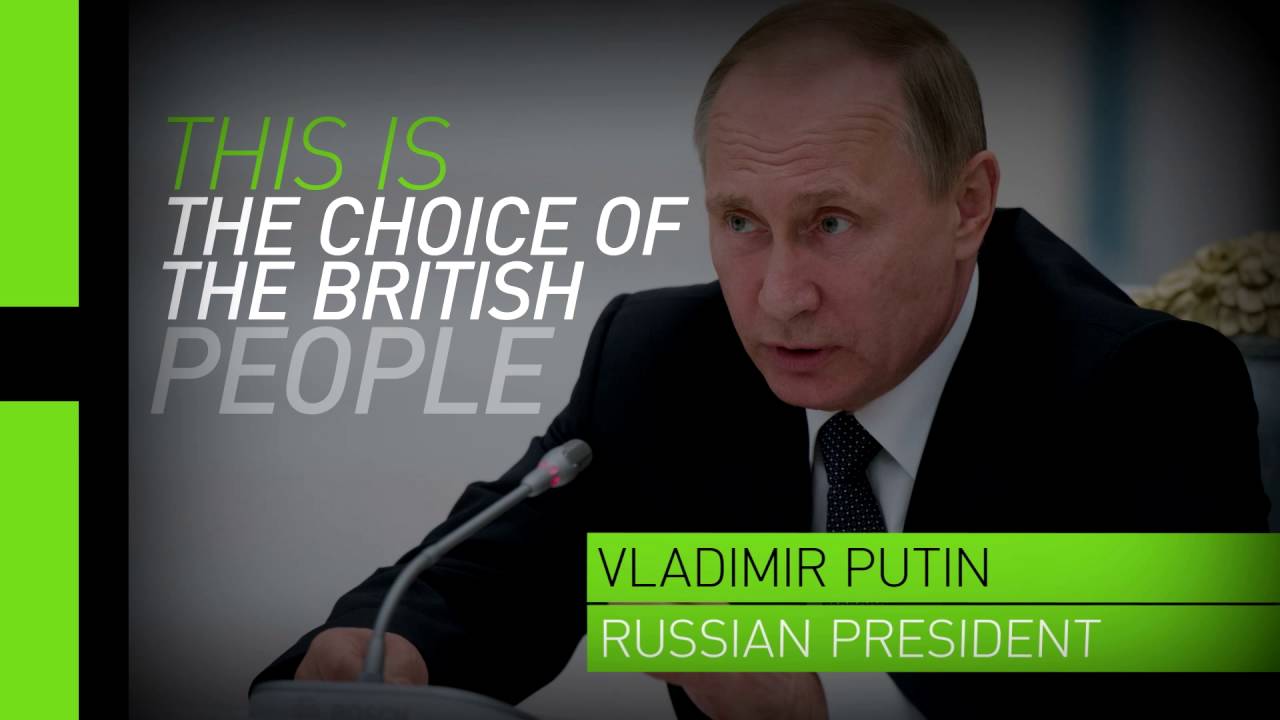

The Kremlin leader understands perfectly well, he says, that he will not be able to defeat the West by economic or military means and thus must choose an indirect approach, one that judo-style exploits the West’s strengths against it. Putin will thus promote populist anger in Western countries with the goal of “converting any vote into a protest.”

There can be “no doubts,” Malgin says, “that Putin’s agents will now push for referenda wherever possible” and on whatever subject, left, right or center, with the goal of achieving the most “destructive” outcome possible. And to that end, he will step up his propaganda directed at Western countries.

Anyone who objects as some have and more will, he continues, Moscow will challenge with the question “Are you against freedom of speech, respected ‘partners’?” To be sure, Russia Today (RT) is “not taken seriously” by many. But it is useful for Putin because of the impact it has on Western journalists who cite it in the name of balance, the current standard of objectivity, and thus spread “Lubyanka fakes” to their audiences.

Sometimes, of course, this will be exposed; but the work is “so total that individual failures will not be able to have an essential impact on the results” the Kremlin seeks, Malgin says, adding ominously that this is the way “the third world war” is being fought, even if one side refuses to acknowledge that fact.

Political editor, Novaya Gazeta

(Image: novayagazeta.ru)

Kirill Martynov, the political editor of Moscow’s “Novaya gazeta,” offers an explanation for why Putin is being so successful in this effort. It is because he appears to understand something that many in the West do not: the way in which the Internet revolution has spread contempt for all elites and expert opinion.

In recent years, he says, “there have been many arguments about what changes the Internet promises us,” especially in the wake of the impact of Twitter on the Arab Spring and the supposedly “liberating potential of new media.” But, he continues, “only now are we beginning to understand how these changes work in fact.”

“It is possible that the main thing that the Internet teaches people is distrust in their own elites,” he argues, noting that “it is difficult to imagine the Trump phenomenon or the ‘incorrect’ voting on Brexit in an era of television” alone. But the Internet in both cases has done its destructive work.

“Now in the new media, we see experts much closer up and in more detail than ever before,” Martynov says. “We observe representatives of the establishment as living people who make mistakes, say stupid things and are laughable.” As a result, “voters in the West no longer want to subordinate themselves to the directives of ‘the empty suits.’”

And that in turn means, he concludes, that “a revision of the social contract in the entire world awaits us.” Such a process will entail many “risks,” including “the collapse of old political alliances and the coming to power of populists.” Those who are banking on this like Putin may thus win, particularly if those he wants to defeat do not recognize the challenge.

Related:

- Kremlin trolls are engaged in massive anti-Ukrainian propaganda in Poland

- Seven strategies of domestic Russian propaganda (Infographic)

- Kremlin disinformation and Ukraine: The language of propaganda

- A guide to Russian propaganda. Part 1: Propaganda prepares Russia for war

- How Russia's worst propaganda myths about Ukraine seep into media language

- 15-point checklist of Putin regime's propaganda techniques

- Propaganda stereotypes paralyze Russia's potential for change