Many commentators are pointing to the influence Vladimir Putin’s irredentist policy in Ukraine is having on non-Russian nations and Russian regions, but few have focused on the way in which some of the dispersed nationalities of the Russian Federation are considering what his promotion of a “Russian world” could mean for them.

And in at least a few cases, including that of the Kazan Tatars, most of whose titular nationality members lives outside the borders of Tatarstan, and the Circassians, who live in several republics as a result of Stalin’s policies, national elites which decide to extrapolate from Putin’s ideas about Russians to their own could have an equally important impact on the future.

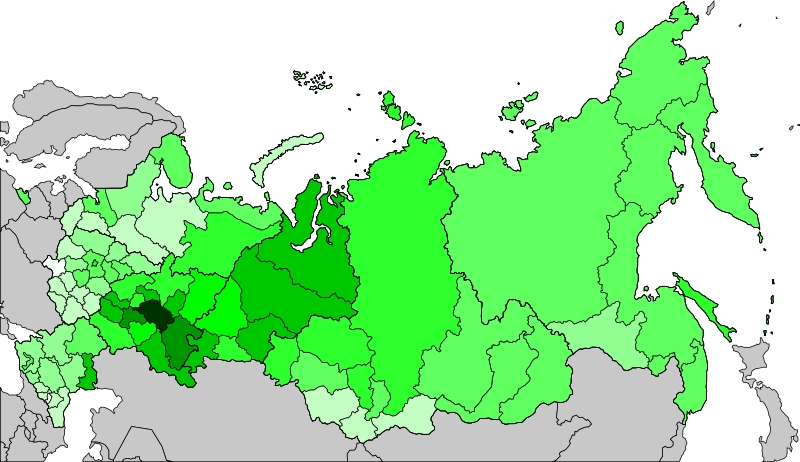

The case of the Volga Tatars is especially striking in this regard. Of the 5.3 million Tatars counted in the 2010 Russian Federation census, only two million lived within the Republic of Tatarstan. A million more lived in neighboring Bashkortostan where they formed 25 percent of the population, slightly less than the titular Bashkirs.

(The division of the closely related Tatars and Bashkirs into two republics in 1920 was Stalin’s first great act of ethnic engineering, one that Moscow has institutionalized by continuing to promote tensions between the Tatars and the Bashkirs, including by installing representatives of each in power there.)

The Volga Tatars, the second largest nation in the Russian Federation, have always felt constrained by this arrangement, believing in many cases that Kazan should play a much bigger role in the life of Bashkortostan than it has been able and that it should speak not just for the residents of Tatarstan but for all the Tatars in the Russian Federation.

This week, in the current issue of “Zvezda Povolzhya,” Damir Iskhakov, a Tatar historian and one of the founders of the All-Tatar Social Center (VTOTs), reiterated those concerns but with a twist: he pointed to Putin’s promotion of a “Russian world” as a model for the Tatars and a “Tatar world” strategy (“Zvezda Povolzhya,” no. 28 (708), July 31-August 13, pp. 1-2).

Not surprisingly, Iskhakov devoted most of his attention to what he said should be a vastly more forward Kazan strategy in neighboring Bashkortostan where he said, the Tatars should be pushing for much greater representation in the senior positions of the government and society there.

His discussions of what Kazan might do and who is might support are interesting in and of themselves – he provides some remarkable insights into the nature of the political relationships among Ufa, Kazan and Moscow – but it is his suggestion that Kazan pursue a “Tatar world” strategy modelled on Putin’s “Russian World” one that is most intriguing.

Were Kazan to do that, it would almost certainly strengthen the ethnic Tatar component of Tatarstan’s identity and trigger conflicts inside other federal subjects where Tatars are numerous, two more unintended, unexpected. and likely unwelcome consequences of Putin’s policies in Ukraine.

[hr]

Photo: Tatars in Russia

Originally publisheed on Window on Eurasia