On May 17, 2016, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny and his family and colleagues from the Anti-Corruption Fund (FBK) were attacked by a hoard of paramilitary “Cossacks” shouting “Get off our land” while police casually looked on. At least one person had to be hospitalized and several others suffered injuries. All were terrorized.

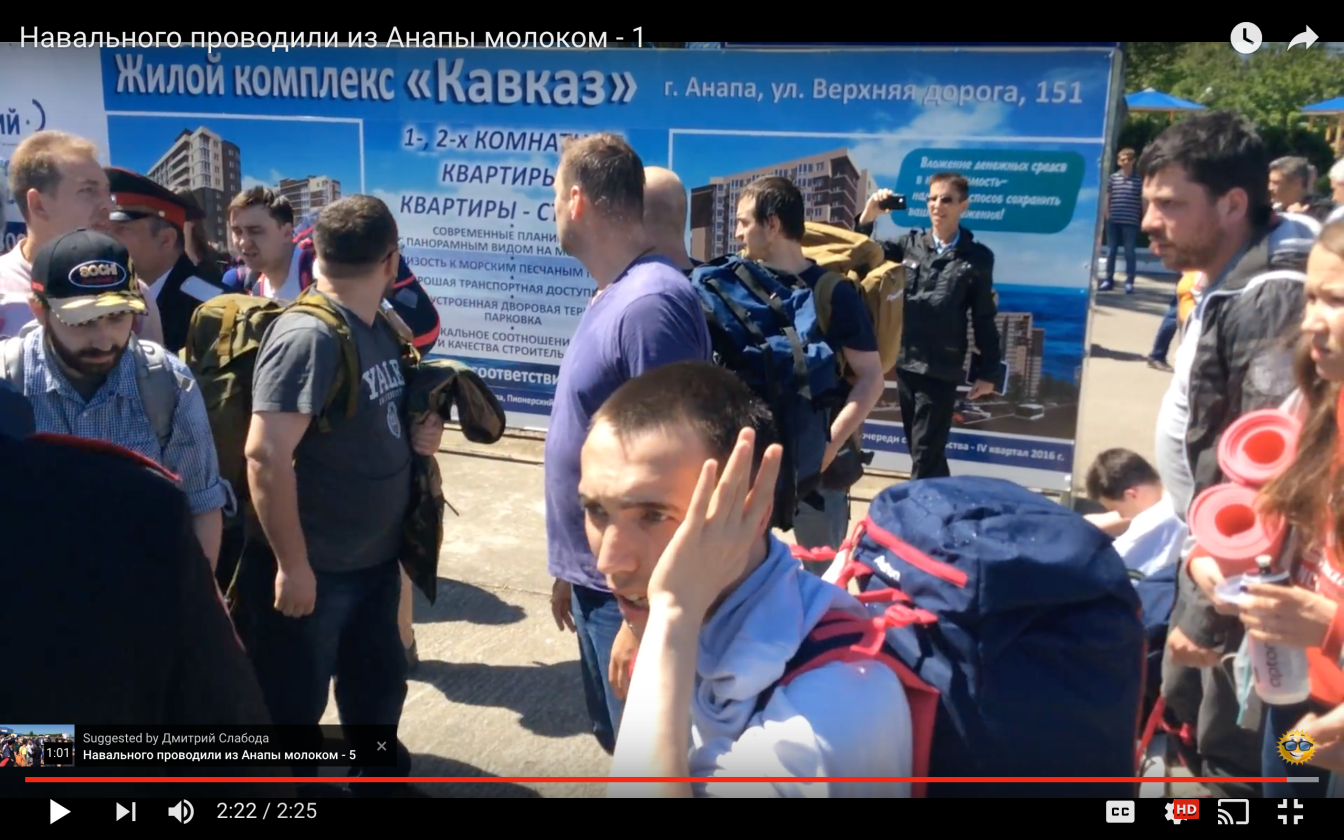

Alexei Navalny, lawyer, anti-corruption activist and politician who came to prominence exposing Russia’s corrupt “crooks and thieves,” was returning from a camping retreat near the Black Sea in southern Russia with family and staff. As they were about to enter the airport terminal in Anapa on their way back to Moscow, carrying all their camping gear and luggage on their backs in large backpacks, they were surrounded by 30-40 men, some in camouflage and black sheepskin “Cossack” hats, others in plain clothes. The group was attacked with containers of milk, as well as taunts about being traitors to Russia. The perpetrators blocked the group’s entrance into the airport and herded them into a circle, around which the men swarmed as if they were encircling prey. Several young men in the group were beaten and kicked, by several “Cossack” attackers at once. An outraged Navalny yelled at them to stop and be mindful that women and children were present. Women screamed. It was a scene of chaos, menace and violence.

Alexei Navalny, lawyer, anti-corruption activist and politician who came to prominence exposing Russia’s corrupt “crooks and thieves,” was returning from a camping retreat near the Black Sea in southern Russia with family and staff. As they were about to enter the airport terminal in Anapa on their way back to Moscow, carrying all their camping gear and luggage on their backs in large backpacks, they were surrounded by 30-40 men, some in camouflage and black sheepskin “Cossack” hats, others in plain clothes. The group was attacked with containers of milk, as well as taunts about being traitors to Russia. The perpetrators blocked the group’s entrance into the airport and herded them into a circle, around which the men swarmed as if they were encircling prey. Several young men in the group were beaten and kicked, by several “Cossack” attackers at once. An outraged Navalny yelled at them to stop and be mindful that women and children were present. Women screamed. It was a scene of chaos, menace and violence.

Another day, another violent attack against Russia’s opposition leaders. We should be used to this by now. In recent months, prominent Russian political figures have been assaulted in a variety of forms and with a variety of substances. They’ve been pummeled with eggs and tomatoes. Cake has been tossed in their faces. Strange green liquids have been hurled at them from quickly fleeing strangers. You might be tempted to think these are silly gags like pie-throwing, a venerable comedic tradition popularized by Vaudevillian slapstick comedy acts. Unpleasant to be sure. But how bad can it really be?

If you are asking this question, you haven’t been paying attention to Russia, particularly since Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012. But don’t feel bad, you’re not alone. Many educated, intelligent people assumed that Russia would naturally become a “normal” European country after the repressive Soviet Union collapsed. They watched as the Iron Curtain was raised and Russians were finally free of totalitarian communism and Stalinist horrors. And, importantly, people were free to leave if they so chose.

It is certainly true that there are no longer travel bans that force people to stay in Russia as there were in the days of the Soviet Union. But, in an ironic twist, oppression that once forced Russians to remain in Russia is now forcing many to leave. Putin’s new wave of authoritarianism has not only ushered in a new wave of emigration, it has unleashed a wave of political terror on those who remain.

Increasingly, life for certain segments of the Russian population entails enduring daily demoralizing degradations Westerners would find shocking, frightening and unbearable. This new form of oppression is in addition to official repression instituted by legislative means, such as the recent laws limiting protest, free speech, annihilating freedom of assembly and the like. This new oppression is also in addition to the unofficial suppression by means of pervasive state media control, censorship and propaganda.

The new oppression in Russia is the conscious creation and promotion by the Kremlin of a culture of hate, fear, and division which has unleashed a barrage of bizarre abusive and menacing acts of psychological cruelty directed at Kremlin critics. This persecution is not only to silence, but to punish and humiliate in the process. I think it’s fair to call this oppression a form of terrorism. Just as the historic Moscow Helsinki Group celebrated its 40th anniversary of human rights breakthroughs, we are witnessing a return to a Russia where human rights abuses are commonplace and perpetrated in a particularly sinister and sadistic manner against a distinct group of new dissidents. Today’s dissidents are opposition politicians, activists, independent journalists, artists, bloggers, pro-democracy protesters, Ukraine supporters, human rights workers, educators, environmentalists, and others critical of Putin or his policies. These dissidents are subjected to extraordinary forms of pressure, fear and intimidation. They are treated so cruelly, and the atmosphere surrounding them feels so dangerous, many have no choice but to leave Russia.

Terror-assaults. Here is a sampling of the types of terror-assaults on Russians during Putin’s rule. Politicians have been pummeled with cake, eggs, tomatoes, liquids. Protesters have been attacked with feces and bleach. Students attending a seminar on Stalin’s terror were attacked with urine. Opposition journalists, including Oleg Kashin and Lev Shlosberg, have been brutally beaten and left for dead. Journalists exposing human rights abuses, including Anna Politkovskaya and Natalya Estemirova, have been outright murdered. Whistleblowers like Sergei Magnitsky were tortured and beaten to death. Whistleblower and Putin critic Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned with radioactive polonium in tony London. Democracy activist Vladimir Kara-Murza Jr. suffered multiple organ failure and barely survived his mysterious poisoning. And of course, charismatic opposition politician Boris Nemtsov was assassinated in the shadow of the Kremlin and Red Square in the heart of Moscow.

Spectrum of violence. Although there is a spectrum of violence targeting today’s dissidents, I would argue that all the attacks, wherever they may fall on that spectrum, from the seemingly mild to the horrific, are forms of systematic political terrorism, part of an overall state-sponsored campaign to silence dissent throughout society using repeated psychological and physical acts of violence. Compared to the worst attacks that have been perpetrated on independent-minded Russians, foodstuffs like cake and eggs are relatively small potatoes, as it were. But even such attacks have a significant psychological impact on their victims given the pervasive menacing climate. They are designed to use the minimum means for maximum psychological effect. The assaults are random and unpredictable in time, place and manner. Although the assaults are becoming more commonplace, the targets are kept off guard, never knowing when or where to expect the next assault. Neither can they predict what substance or how many attackers there will be. Victims cannot know whether the next time the outcome won’t be serious and truly life-threatening. Every assault undoubtedly elicits fears of becoming the next Shlosberg or Kara-Murza or god-forbid Nemtsov. The only certainty is that there will be more attacks.

Russia’s new dissidents have to live with this constant fear of assault. This in itself is a form of psychological terror. Substantively, the terror-assaults themselves, from the hurling of eggs to the beatings and murders, all share a minimum intent to inflict psychological violence by besieging victims in an ominous atmosphere of menace and fear while carrying out acts of humiliation and dehumanization. Such unmistakable and deliberate psychological terror has many victims: the dissidents, their families, and society at large. Many walk with the visible scars of being terrorized by abusive acts of violence. Many more live with the psychological scars, not manifest on their flesh but no less traumatic. It’s worth noting that the perpetrators too are impacted by the violence they do to others. Their souls are scarred as well. As are those who see but choose to look the other way. All of this makes for a society plagued by a distinct culture of terror, more widespread than appears at first glance, and rarely noticed or discussed seriously in the West.

Psychological component. English doesn’t even have good words to convey the kinds of deliberately staged, premeditated terror-assaults of psychological and physical abuse we are seeing more and more of in Russia today. In Russian they are often called “провокации” or “provocations” and they have become a powerful weapon in the Kremlin’s unofficial arsenal to terrorize people, both the “undesirable” critics as such, and as a signal to the wider society

of what’s permissible and what’s punishable behavior.

Provocations are by definition political acts with a psychological component. They are acts designed to incite others to feel an emotion, usually anger, so strong that they are forced – provoked – to act on that feeling, often against their own will, reason and interest. In Russia, provocations have a unique flavor. Typical provocations have an element of dirty trickery, which in Russian is conveyed by the word “подлость” (pódlost’). This is also a difficult and complex Russian concept that includes shades of under-handedness, meanness, cruelty, baseness, vileness and generally conveys the sense of doing something morally repugnant.

The terror-assault is a nasty mix of the strategic power-play of Machiavelli, the mafia-cruelty of Goodfellas and the downright depravity of drunk football goons in a dark alley all rolled into one.

By terrorizing a few, in a particularly sadistic and humiliating manner, all get the message: Stop criticizing Putin; stop trying to change Russia; just conform to the Kremlin line, or you’re be mercilessly abused and hounded out of the country.

Terror and collective fear have a long and tragic past in Russia. The word “terror” defines whole eras of Russian history, from Ivan the Terrible’s Reign of Terror to the Bolshevik’s Red Terror and of course Stalin’s Great Terror. Russians and others still are inclined to reserve this word to discuss some of the most horrific atrocities in history, involving the deaths of millions. The unfathomable bloodshed and untold scores of victims on Russian soil have been so tragic, I don’t think many are prepared to view the psychological effects of actions in Russia today as a serious form of terror.

But Russians do feel the terror. They just use other words. Russians seem more comfortable using the word “мучение” (pronounced “muchénie”) to describe their sense of being abused by these terror-assaults. Muchenie is a noun that combines elements of hardship, torment, torture, punishment, and suffering. It can also describe the feeling of being besieged by forms of cruelty, though not necessarily by an agent. Sometimes, it describes a kind of fatalistic condition, i.e., that’s just the way life is.

Criminal procedure as a weapon. Russian authorities do their share of making dissidents suffer. For example, Russia’s dissidents are regularly and repeatedly subjected to government searches and raids conducted at ungodly hours. Often there is a pretext of a criminal investigation. Ilya Yashin has commented on the feeling of dread just hearing noises outside one’s door in the wee morning hours. Raids are also even conducted at the homes of parents and relatives of dissidents. Imagine the panic one feels getting an early morning phone call from an elderly parent saying their apartment is being searched because the authorities don’t like you. After several such experiences, dissidents begin to feel terrorized and under siege.

Another recent incident of what is unmistakably a terror-assault appeared as a video post on Instagram. Two prominent politicians, former government minister Mikhail Kasyanov and Open Russia coordinator Vladimir Kara-Murza Jr. were in Strasbourg, France, to testify before the International Criminal Court about the assassination of their colleague Boris Nemtsov. Within days after their trip, a terrifying video of the two of them in Strasbourg went viral. It showed the two men with friends being watched and secretly filmed through a sniper’s scope atop a barrel of a gun. It was posted by Putin appointee Ramzan Kadyrov, head of Chechnya, who has been a prime aider and abetter and likely perpetrator of terror in Russia.

There are also many cases of Russia’s judicial system being used as a weapon against dissidents. Not only are dissidents targeted for criminal prosecution, but there is an additional element of menacing unpredictability hanging over many because they can be charged and arrested on bogus charges at any time, even for events that took place years ago. Just in case he had any notions of returning to Russia, the politically active Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who spent 10 years in prison as a political vendetta, was again charged in December 2015 in a 1998 murder case. Four years after the mass protests on Bolotnaya Square, people are still being brought up on criminal charges. Many dissidents simply find themselves targets of criminal witchhunts for their political activity.

Alexei Navalny has had to defend himself in court against false criminal charges and fabricated evidence in public trials more than once. These fabricated cases of fraud and embezzlement are then used on state-run media and pro-Kremlin social media to portray Navalny, the guy who uncovers criminal corruption, as a criminal and thief himself. All the while his family is made to worry about his fate and theirs should he be sent to prison. In one telling incident, Navalny arrived in court on the day of his sentencing on carrying a full backpack, fully expecting to be found guilty and taken to prison straightaway after the verdict. Hundreds of protesters came to court to show their support. After hours of monotone reading of the verdict (think Leviathan), Navalny suddenly learns his sentence has been suspended and he was going to be a free man. But he couldn’t even savor the miracle victory or enjoy a moment of joy or peace, because a moment later, the judge announced she was condemning his brother Oleg to 3 1/2 years in a labor camp. Just like that, in a fleeting moment, Alexey went from joy to horror. His response

to the court that day was pure agony: “Why are you torturing me like this?” (He used the word “muchit’.”)

I was immediately reminded of Russian literary giant Fyodor Dostoevsky’s ordeal of being subjected to a mock execution as a young man. Dostoevsky belonged to the Petrashevsky Circle, a group of writers and intellectuals whose arrest was ordered by Tsar Nicholas I. Among other charges, Dostoevsky was accused of conspiring to produce anti-government propaganda. After the trial, he and others were sentenced to death by firing squad. They were led out into a courtyard and tied to pillars to await their execution. The order to fire was given, and then immediately another order followed to stop the executions. A messenger had arrived stating that the Tsar had commuted the death sentences to hard labor. Importantly, this was not simply a fateful moment, but a deliberate act of cruelty and terror, so intended by the Tsar who specifically instructed that his message be read at the last possible moment before they were shot. Dostoevsky survived this act of terror, but not unscathed. He was haunted by the trauma for the rest of his life. It’s impossible not to carry the scars of psychological abuse and deliberate acts of violence.

Such acts are also regularly used to create the conditions for the state to initiate criminal proceedings against protesters. This is essentially how anti-protest law Article 212.1 has become an easy means for the state to pick off dissidents. Remember Ildar Dadin was arrested after he was harassed by others, turning an ostensibly legal one-person picket into an illegal public rally. He was tried, convicted and serving more than 2 years in prison.

Proxy perpetrators. Many of the terror perpetrators see themselves as Russian patriots, soldiers for Putin, not unlike far-right nationalist vigilante groups like the Hitler Youth. Pro-Kremlin groups like NOD, SERB, and Nashi consider government critics like Navalny and other opposition members and dissidents as prime targets for terror-assaults because these citizens have been routinely labeled throughout the media as traitors to Russia. Putin himself has even promoted using Stalinist rhetoric including infamous notions such as “enemy of the people” and “fifth column” to refer to his political opposition. Putin has also openly condemned opposition figures as foreign agents whom he accuses of trying to undermine Russia, doing the bidding of foreign governments, and financed, invariably, by the CIA and the US State Department, goes the propaganda.

This isn’t a recipe for the healthy development of a country. For a country to prosper in the global economy, which Russia surely wants, independent citizens and critical thinkers should be prized not terrorized.

But Russia is not a normal country, not in any Western sense. It’s still suffering from Soviet deprivation and post-Soviet trauma, and now it’s suffering the trauma of Putin’s lurching Russia back onto the world stage. The Kremlin has its own idea of what normal is, and in a characteristically top-down fashion, brutal and otherwise, it has both reflected and disseminated its narrow view of normal. Before you scream “Russophobia,” let me assure you that this is a sentiment shared by many inside and outside Russia. There are very serious abuses and inhumanity going down in Russia today, unimaginable and often indescribable to people who live in Western countries. Kseniya Kirillova wrote a brilliant essay on what this has meant for Russians in the past as well as today. She argues that this is essentially Russia’s curse: a deep moral failing of the government to develop a basic normal society where people are allowed to live normal lives, to be decent human beings who are neither forced to conform nor punished for not conforming to the Kremlin’s narrow view of normalcy.

And so every news day seems to bring a new low and a new twist to the terror-assaults suffered by Russians. Anti-corruption blogger and opposition leader, Alexey Navalny who regularly exposes the corruption of Putin and his circle of “crooks and thieves” gets more abuse than most. The attack on him this week is particularly emblematic of the kind of sinister abuse and psychological terror that’s become common in Russia. Since the assault was recorded and uploaded to YouTube, as many of these are in order to spread the terror message of humiliation and fear on social and state media, it provides an excellent opportunity to discuss some of the most disturbing aspects of these modern morally repugnant terror “provocations” against dissidents, updated to fit the social media and disinformation age.

Below is a summary of an in-depth analysis I made in a separate post of the assault at the Anapa Airport on May 17. The full analysis helps Westerners get a feel for what opposition figures like Navalny and their families go through in Russia. Even the title of the video is an attempt at humiliation, sarcastically titling a grueling ordeal and vicious attack “Navalny Was Escorted Out of Anapa with Milk.” With everything happening so quickly, it’s nearly impossible to understand the stress and terror dissidents are subjected to without stopping to look frame-by-frame at the scene and the progression of violence, physical as well as psychological. The faces of the victims display the grim impact of the terror. Similarly, the faces of the perpetrators display satisfaction with their own cruelty.

As the video begins, Navalny’s group of a dozen or so people, workers and volunteers from the Anti-Corruption Foundation and their spouses and families, are seen walking toward the Anapa Airport terminal carrying luggage and large backpacks. They are returning from a 4-day camping trip, a team-building retreat, as Navalny called it, to get away from Moscow and regroup for a few days of rest in the country.

The group is walking in a column with their heads down, and eyes looking down toward the ground. Clearly they see trouble is around them, and their body language expresses their instinctive reactions to the tense and stressful atmosphere. There are in fact dozens of men, approximately 40, outside the airport terminal entrance staring at the group, following alongside them, and taunting them. The menacing men are dressed both in paramilitary camouflage as well as ordinary clothing, some wearing the characteristic sheepskin hat of the paramilitary Cossacks. You might remember that it was a group of Cossacks who whipped Pussy Riot members in Sochi during the Olympics in 2014.

Navalny and members of his Anti-Corruption Fund are young but not naive. They have been victims of many previous “provocations” that took place at political rallies or campaign stops. From these previous attacks, they understood full well that this was going to be another menacing act. But they were on vacation, with their families, so, once again, they are caught off-guard, unprepared for the coming assault. What should they expect in this different circumstance? Would something get thrown at them? Or would it be worse? They were with family and loved ones, even young children were present. So that added to the feeling of menace and fear, undoubtedly. Whatever was going to happen, they understood right away that they were going to be targets of some sadistic form of humiliation, some deliberate act, planned in advance, coordinated with police and/or security forces, with cameras at the ready to capture each humiliating frame. Since this was a public place, outside an airport, the planning was probably greater than elsewhere, since Russia like most nations has recently increased security and police presence at airports due to the threat of terrorism. (Ironic, isn’t it?)

Navalny and members of his Anti-Corruption Fund are young but not naive. They have been victims of many previous “provocations” that took place at political rallies or campaign stops. From these previous attacks, they understood full well that this was going to be another menacing act. But they were on vacation, with their families, so, once again, they are caught off-guard, unprepared for the coming assault. What should they expect in this different circumstance? Would something get thrown at them? Or would it be worse? They were with family and loved ones, even young children were present. So that added to the feeling of menace and fear, undoubtedly. Whatever was going to happen, they understood right away that they were going to be targets of some sadistic form of humiliation, some deliberate act, planned in advance, coordinated with police and/or security forces, with cameras at the ready to capture each humiliating frame. Since this was a public place, outside an airport, the planning was probably greater than elsewhere, since Russia like most nations has recently increased security and police presence at airports due to the threat of terrorism. (Ironic, isn’t it?)

Notice that in stark contrast to the defensive stance of Navalny’s group are the offensive postures of the men surrounding the group, the man in the black Cossack hat and camo in the foreground stares piercingly and directly at the group as they walk by. He is also distinctly physically leaning in leftwards in the direction of the group, a very aggressive and menacing body gesture. Notice that he is hiding his hands and an object behind his back.

Navalny’s group procession with their heads instinctively down is eerily reminiscent of captive prisoners of war in a humiliating parade before their captors. They even look like they’re about to be spat on.

Instead of humiliating spit, however, here come liters of humiliating milk. The “Cossack” in the hat who stood leaning over the group menacingly a moment ago, now takes aim with his hidden object, and is about to throw the object in his hands with full force at the group. You can also see that several other men in the same black Cossack hats have now attacked Navalny simultaneously with a tremendous amount of liquid. The perpetrators later said to Meduza

media, they were simply intending to throw some milk.

Milk sounds so harmless, but certainly several large jugs of milk thrown directly at a person in a coordinated assault are far from harmless. The substance could have been something more dangerous, certainly. But having anything thrown at your body is jarring, painful and frightening. And if you’ve been attacked before, are surrounded by many angry men hurling insults as well as hurling objects forcefully at you, this is anything but harmless. It almost knocks a large man like Navalny to the ground. This is a vicious and cruel coordinated, premeditated assault.

The “welcome party” stands in front of the airport terminal entrance. Navalny and his group are surrounded by several rows of paramilitary men awaiting them and blocking their passage to the airport. He is on their turf, as they shout “Get off our land.” Notice the menacing, bullying stance of several of the uniformed men staring down the approaching group: arms crossed, legs apart. Just waiting boldly for their prey.

The gray-haired man in the yellow shirt is Nikolai Nesterenko, a local ataman, leader of the local “Cossacks” and the attack. Nesterenko stands with his hands on his hips in a macho confrontational stance. He’s leaning on one leg and starts to laugh and mockingly clap at Navalny.

What’s striking here is that Nesterenko, who revels in having ensnared his victims, laughing and mocking Navalny, is standing right next to the frightened young son of Navalny. Nesterenko even seems to be holding the young Navalny boy’s hand. Nesterenko is fully enjoying inflicting his terror.

Navalny’s group is now huddled closer together, as the attackers surround and begin herding the group into a kettle, actually swarming around them. The group is surrounded by men, several rows deep and unable to break free. The atmosphere becomes more frightening and chaotic. The man in the blue shirt, Artem Torchinsky, spreads his arms out to protect Navalny and others from the “Cossacks” blocking their passage and by now clearly terrorizing the group.

As they’re being herded, the man in the red shirt tries to get through the blockade of men swarming around them and shoves his elbow into Nesterenko, the leader of the group who has been taunting and terrorizing them. Nesterenko backs away. At this point the “Cossacks” start to mercilessly pick their beating victims, beginning with the man in red.

The claim that the “Cossacks” weren’t at all intending to beat anyone until they saw the elbow shoved into a defenseless older man falls flat. This is a classic pretext for violence. They created fear and menace, humiliated and terrorized a group of young men, women and children, blocked their passage, and then when someone has the temerity to break through the blockade, they blame him for “provoking” the subsequent violence. As the leader who likely organized the assault, it’s hard to call Nesterenko “defenseless.” Furthermore, the attack was disproportionate to any “punishment” they might have deemed appropriate for an elbow shove.

Indeed, the frame analysis confirms that Navalny’s group was doing all they could to avoid confrontation. It also shows the “Cossacks” were doing all they could to menace and humiliate their victims. If they only wanted to punish the man in red for his elbow blow, then there was no need to beat up others who were doing nothing but standing there. Artem Torchinsky tried to stop them from ganging up on one man, and subsequently himself became the victim of the most brutal beating of all. In this frame the attackers shouted “Beat him, beat him!” while as many as 8 men pounced on him until he fell backward to the ground. And they didn’t stop there. Several "Cossacks" continued to kick him while he was down.

This frame is important because you can see Torchinsky is on the ground, his blue shirt is all that is visible in this frame. You can also see his attackers in camo and hats with their arms up as if balancing themselves. This is presumably when they are kicking Torchinsky with their feet. The woman in red looks around aghast. Navalny can be heard screaming “You’re kicking a defenseless man on the ground!” Torchinsky is later sent to the hospital for these injuries.

The assault continued as more attackers pounced on other members of Navalny’s group. Here several “Cossacks” are surrounding the young man in the white t-shirt and sunglasses, grabbing him menacingly by the back of the neck.

As at least 2 men assault the man in white, shoving their hands in his face, a policeman in uniform (and cap), from the Russian Interior Ministry, according to his badge, is looking on just to their right, and doing nothing to stop the assault.

As yet another man in Navalny’s group is attacked from behind, a policeman in uniform watches as an innocent man is ganged up on by 3 “Cossacks.” The attackers grab their victims from behind, using multiple attackers on one individual. This ensures an unfair and unequal fight, where the victim is overpowered and outnumbered. It’s difficult not to conclude that Russian officials weren’t complicit in this terror-assault.

By now, Navalny and others, especially the women could be heard screaming for help from the police, who failed to respond. Several more harrowing moments are visible as the woman in red tries to stop yet another attack on her husband, the man in the red shirt.

By now, Navalny and others, especially the women could be heard screaming for help from the police, who failed to respond. Several more harrowing moments are visible as the woman in red tries to stop yet another attack on her husband, the man in the red shirt.

By the end of the video, most of the horror has stopped. The height of the terror-assault lasted a little over 2 minutes. Navalny and a dozen or so members of his group look stunned and exhausted.

By the end of the video, most of the horror has stopped. The height of the terror-assault lasted a little over 2 minutes. Navalny and a dozen or so members of his group look stunned and exhausted.

After the group finally made it out of there and back to Moscow, Navalny posted some photos as well as an account of what happened. He was able to provide more context as well as more background on the perpetrators. Significantly, he stated that the attack was not simply by “Cossacks,” but likely coordinated by a local gangster, and ordered by Prosecutor General Chaika (about whom Navalny and FBK produced a documentary exposing criminal corruption links). He also described a previous similar encounter on the front end of their trip which turns out to have been a prelude to the full-fledged attack seen here.

Navalny and his group were undeniably terrorized. Seeing the assault frame by frame captures the gravity of the attack. It allows us to view the visible pain and torment that Navalny and Russian dissidents like him have to endure all too often in Putin’s Russia. We can also see the faces of the perpetrators, some smiling, others in proud arrogant stances, as they carry out their acts of despicable cruelty and humiliation. What’s perhaps equally or more disturbing is seeing so clearly not only the climate of terror and menace but that it is obviously approved by state actors and guided by Kremlin narratives. The Cossacks’ message, as told to Echo Moscow media and described by Ilya Varlamov, was “to show that Navalny, who lives on American money, does not belong here.”

That these terror-assaults are increasing in frequency and gravity only highlights the extreme degradation of morality and humanity inside Putin’s Russia. No, he is not sending masses of people to the GULAG or executing them on the spot. He couldn’t do that without an iron curtain. But the atmosphere his Kremlin has created and continues to encourage is terrorizing its citizens. The psychological effects on such prolonged stress and trauma on innocent people are bound to have terrible consequences for Russian society for some time to come.

What we can do in the Western media is take the time to highlight and discuss these horrible abuses seriously. I’m convinced that most people here simply have no clue about the appalling circumstances of everyday life for Russia’s dissidents, so vividly exposed in the screenshots above. I purposefully use that word “dissidents” because it is a powerful term with a history of struggle and victory. Words such as “protesters” and “activists” don’t adequately convey their true role or experience in Russia today. These people are fighting and risking their healthy and sanity for things we take for granted. We can criticize our government, mock our president, protest against injustice, and we can go back home, have dinner with our family, and not fear that the next time we go on vacation or step outside, we will be terrorized by government-sponsored vigilantes calling us traitors, hurling insults and objects, trying to scare us into silence or out of our homeland.

Putin’s reign of terror against Russia’s new dissidents can’t stop if the world doesn’t even stop to pay attention to it and call it what it is.

Related:

- The price for a clear conscience in Russia

- Russia's criminalization of protest: Ildar Dadin's appeal and Article 212.1

- Chekist regime and criminal world in Russia now 'completely coincide,' Portnikov says

- Kremlin's censorship of Shenderovich interview spotlights Putin's mafia connections

- Ever more Russians are at risk of repression as Putin's Russia heads toward totalitarianism

- Putin's Russia well on its way to 'criminal neo-totalitarianism' with a 'neo-terror' and a 'neo-GULAG,' Pastukhov says

- Heroes past and present: Remembering Bolotnaya and Russia's Victory Day

- The Kremlin's revival of the "red project" may ultimately turn against it

- Worldwide rallies planned to commemorate anniversary of Boris Nemtsov murder

- Is Putin poisoning his opponents?

- Not dead yet: Russia's opposition rallies in first major protest since Nemtsov assassination

- Activists in Russia petition international community to investigate Boris Nemtsov assassination