“Reconciliation is a good thing, and hostility is bad,” Igor Klyamkin says. “But there are reconciliations and reconciliations,” some of which open a path to a better future and others of which point to the return of the evils of the past. Unfortunately, the one on offer in Russia today is more likely to be of the latter kind.

In a commentary on Kasparov.ru today, the longtime Moscow commentator says that “the reconciliation being initiated in Russia will mark the completion of the opposition of two imperial projects, the red imperial and the white imperial” by “synthesizing” the imperialism of both.

In fact, Klyamkin says, that kind of “reconciliation” has “already taken place” as shown in 2014 when, with the seizure of Crimea and intervention in the Donbas, the two imperial traditions were presented as one.” But the question remains how long that will last. “Perphaps,” he says, “by 2017 this will become clear.”

In fact, Klyamkin says, that kind of “reconciliation” has “already taken place” as shown in 2014 when, with the seizure of Crimea and intervention in the Donbas, the two imperial traditions were presented as one.” But the question remains how long that will last. “Perphaps,” he says, “by 2017 this will become clear.”

A clear indication of the accuracy of Klyamkin’s analysis and of the difficulties Moscow will have in maintaining it is provided by Moscow’s current crackdown on several groups of Cossacks, a group whose members fought not only on the red and white sides in the Russian Civil War but also in some cases for their own right of self-determination.

Russian investigators continued their search of the contents of the Museum of Anti-Bolshevik Resistance in Podolsk and launched a new one at the memorial complex devoted to The Don Cossacks in the Struggle with Bolshevism” in Elanskaya. In justifying their actions, officials said that they have found “anti-Russian literature.”

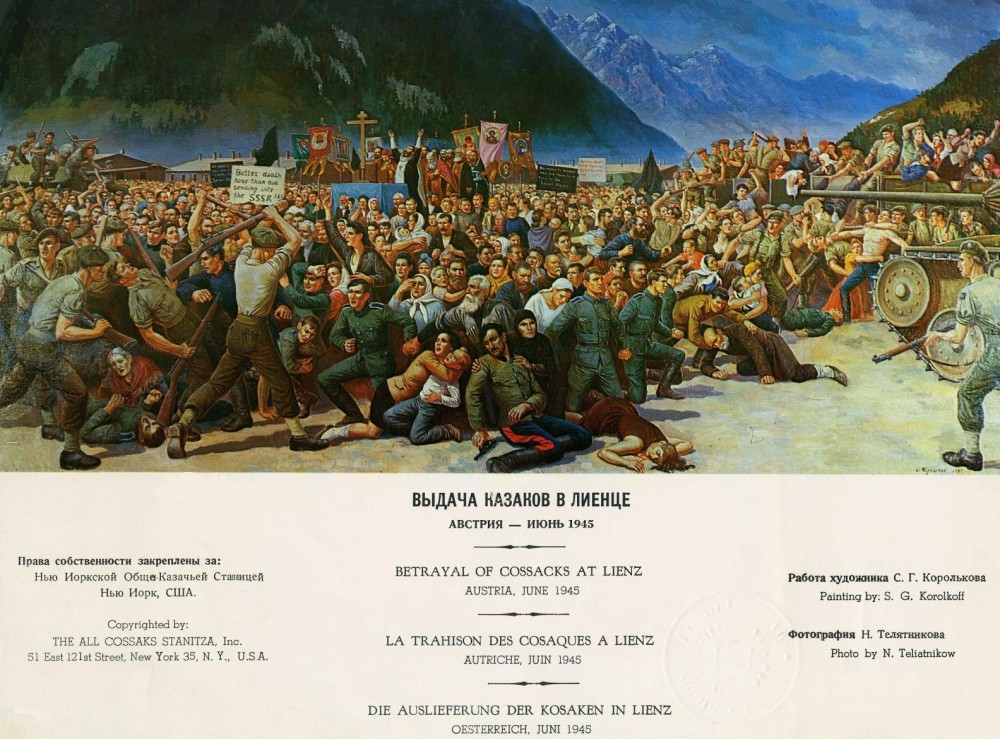

The first has attracted attention because Russian officials had blocked the museum’s director, Vladimir Melnikov, from traveling to Lienz to take part in memorial services devoted to the 70th anniversary of the Western Allies’ handling over of Cossacks and others to the Soviets at the end of World War II.

The second has received attention because of the criminal case against Don Ataman Yury Churekov, who was also prevented from traveling to the Austrian city for those ceremonies, for allegedly bringing weapons back to his home region from the breakaway regions in Ukraine’s Donbas.

In an interview with Radio Liberty, Melikhov said that “the repressions against [him] are the result of the policy of rehabilitation of Stalin now being conducted in [Russia] and revenge for his personal position on the anti-Ukrainian war,” a campaign that he describes as “amoral and shameful.” (Churekov in contrast supports Moscow’s policies in Ukraine.)

Melikhov says that he and his fellow Cossacks want that “people will become responsible for their own lives just as their ancestors were.” How possible that is in Russia today is something they are seeking to find out, at a time when the regime is blaming groups for what they did or didn’t do in 1917 or 1990 rather than where they are now.

This reflects the continuing effort of Moscow to “destroy this culture” and to deprive ordinary people of honor, a sense of worth, “and what is most important, responsibility.” Unfortunately, those are not values which Russia’s current rulers value. What they want is for people to do what they are told and hate those they are told to hate.

As Melikhov says, the Cossacks have been repressed “always, especially after the Civil War, precisely as a result of their political culture, independence and the level of responsibility” they displayed. Unlike some others, they didn’t blame others for their mistakes but rather took full responsibility for their lives and actions.

Currently, Moscow is seeking “to exclude [the Cossacks] from the political life of the country by setting up [what the regime calls] registered Cossacks and calling them the true Cossacks,” he continued. But “this is an absolute stupidity because the majority of people in this register have nothing to do with the Cossacks.”

Such actions as these and the searches and arrests of the last ten days, Melikhov says, will not affect the genuine Cossacks. They will continue their struggle, although he adds that they will stop exhibiting things in their museums and memorials that could lead to an exacerbation of tensions in Russian society.