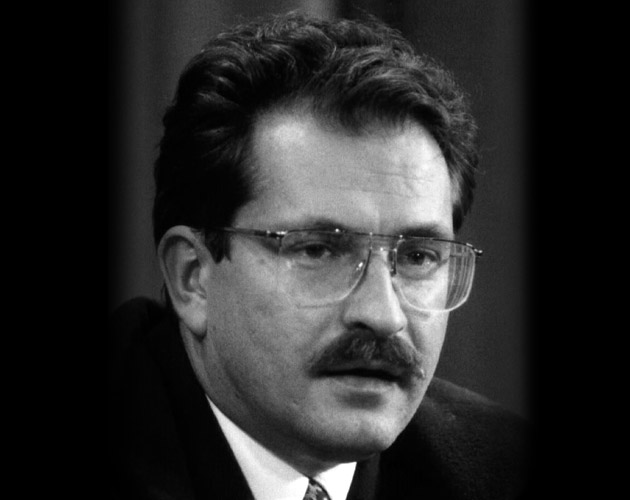

The horror and revulsion all people of good will feel about the murder of Boris Nemtsov in the shadow of the Kremlin has led many to treat this latest crime as if it were something new. In fact, the killing of Nemtsov is only the latest example of Vladimir Putin’s much-tested approach to dealing with his political enemies.

That approach, as Ilya Milshteyn suggests, has now become almost institutionalized. First, Putin marginalizes his enemies, then he or his allies kill them, and then he muddies the water by putting out multiple versions of what supposedly has happened, confident that few will connect the dots and hold him responsible.

That was what happened in the case of Galina Starovoitova. That was what happened in the case of Sergey Yushchenkov. That was what happened in the case of Anna Politkovskaya. And that is what is happening in the case of Boris Nemtsov. All of them were “driven in the status of marginal figures and then killed.”

But all too many people are not prepared to recognize that reality, either out of fear in the case of many in Russia itself who even now are asking “who will be next?” or out of concern in the case of some Western leaders that speaking truth about what Putin is about could provoke the Kremlin leader even more.

Both groups need to follow the advice of the late Pope John Paul who told his fellow Poles that they must “not be afraid.” Boris Nemtsov wasn’t, and neither must Russians nor Western leaders. Instead, they must recognize that they are not dealing with a normal leader but with a dangerously abnormal one.

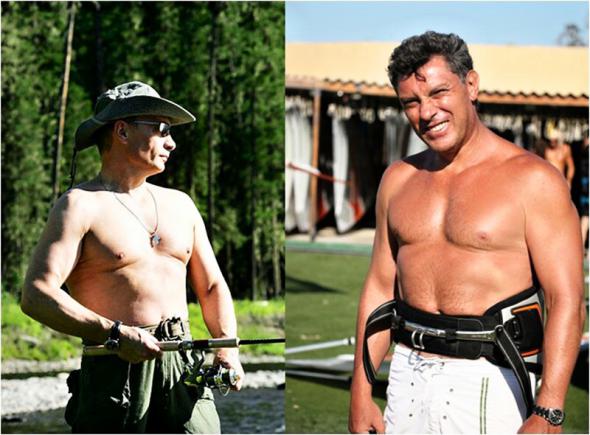

Normal politicians forget about those who cannot challenge them. The books they write and the meetings they organize or speak to can all be ignored. But Putin is not a normal politician, and he does not respond that way. Instead, he focuses on those who disagree with him, seeks to marginalize them, and then directly or indirectly removes them from the scene.

Putin cracks down on such people as his enemies, and he and his minions call them exactly that, enemies, “agents of the State Department, a fifth column, and various other words which in other times would have meant execution of the camps, but in ours provoke extra-judicial violence.”

All this is because the regime Putin has built in the Russian Federation is “simply unthinkable without hatred.” That is its core value, “and the entire history of Putin’s Russia is the history of capably directed hatred toward various individuals, social groups, countries and nations.”

“First there were the Chechens, then the oligarchs with their television channels, later the Georgians, now the Ukrainians, Europeans, Americans, and always those who disagree,” Milshteyn says. And when something awful happens, Putin and the Kremlin PR operation goes into overdrive to push multiple versions to obscure what is going on.

Putin’s press secretary yesterday said that the killing of Nemtsov was a provocation against the Kremlin. “In fact,” Milshteyn asks, “who could have decided on such a step besides enemies and conspirators? Obama? Merkel? Navalny? It is too bad,” he continues, that “Berezovsky is dead because then it would have been convenient to blame him” as well.

Putin and his accomplices should be charged with “incitement to murder,” which is a crime under the Russian criminal code. But he and they have learned that the use of hatred and fear not only protects them from that but brings them major political dividends – and they aren’t about to change either voluntarily.