Yuriy Lukanov has a long history of journalism in Ukraine. As a journalist whose career spans over four decades, Lukanov has covered events like the 1986 Chornobyl disaster, Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia, the 2013-2014 Euromaidan Revolution, and more recently, the Russian-Ukrainian War. Lukanov is also a novelist and short-story author. It is perhaps no surprise then that Lukanov’s career might inspire a novel based on the professional threats, disturbances, and turbulences he has experienced over his decades-long career.

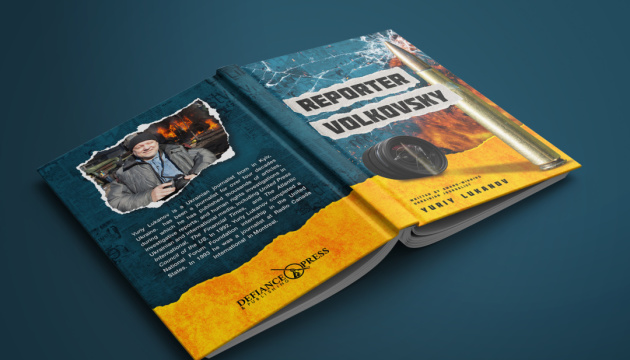

These inspirations help shape the basis of Reporter Volkovsky, published in English by Defiance Press (2023). In Reporter Volkovksy, readers discover a geographic and political situation that is, sadly, not so much fiction as it is a reality that many Ukrainians have lived since the 2013-2014 Euromaidan Revolution.

The preface of Reporter Volkovsky opens with an imperative question: “Why do reporters hurry to become Hemingway?” However, the introspection with which Ukrainian reporters have added to the fiction which they write far surpasses that of Hemingway’s, and Lukanov’s novel is no exception. Lukanov poses, “I suppose that fiction, compared to documentaries, provides much greater opportunities for understanding reality, including the terrible reality of war.”

From the beginning, Lukanov’s writing slowly steeps readers in war’s realities, and similarly to Mstyslav Chernov’s The Dreamtime, Reporter Volkovsky examines the fine lines separating disinformation, propaganda, and truth and how a massive Russian misinformation campaign stoked the flames of discontent and waged an information war against Kyiv.

This type of propaganda continues to confuse and baffle pro-Ukraine officials who encounter Russian support in east Ukraine. An April 2023 The New York Times article affirms that one year into Russia’s full-scale invasion, the rhetoric that Ukrainian forces shell their own people is the line many repeat.

Lukanov’s novel, nonetheless, alludes to the historical propaganda on which the Soviet Union initially relied in order to dupe its people into believing in its power. For example, the novel’s main character, Volkovsky, makes a unique assertion about this:

“Finally, he’d decided that it was Russians’ faith in enemies, who only dreamt about destroying Russia, that was making itself felt. After 1991, “Ukrainian brothers” who dared betray their “older brother” by declaring independence had been turned against as well.”

Russian forces have waged a relentless propaganda war in Donbas, Ukraine’s eastern and most Pro-Russian region. As We Are Ukraine states, “The ‘brotherly bond’ between Ukraine and Russia is a common delusion that emerged because of Kremlin propaganda.’” The usage of the term “brother” in reference to Russia and Ukraine is a manipulative one which erases Ukraine’s past and independent existence.

Lukanov also explores another aspect of Russian disinformation and propaganda that unfortunately found its way into conservative American rhetoric fueling anti-Ukrainian sentiment in the United States. Volkovsky observes, “Western Ukrainian roots automatically gave grounds for the accusation of hostility towards the Russians.” History is a battlefield between Ukraine and Russia, and Russia has repeatedly referred to the Kyiv government as “fascists,” “Nazis,” and “Banderites.”

For Western readers unfamiliar with history and terminology, “Banderites’ may be a confusing term. It refers to the faction of anti-Soviet partisans in World War II led by the controversial figure Stepan Bandera. As a 2014 Euromaidan Press article states, the assertion “Western Ukraine is the lair of Banderites, and Lviv is their capital” results from century-long propaganda and an “unwillingness to investigate the issue independently.” The propaganda paints Lviv as the most “‘Banderised” city, where Russians are killed and anyone who says a Russian word gets shot.” In the novel, Volkovsky makes a keen observation about the eerie power of such propaganda:

“That’s how, little by little, the Russians’ idea that they were hated by Ukrainians was formed. In Crimea or in the West–it didn’t matter. However, it didn’t only apply to Ukraine. Everyone in the world hated Russians.”

The “Everyone in the world hated Russians” is a line that Kremlin officials have repeated ad nauseam, especially as numerous countries instituted travel bans and economic sanctions against Russian officials and citizens.

While the novel carefully explores the immense power of immense propaganda, it also inspects the consequences of torture and war on the average citizen. This first appears when Volkovsky is arrested for being a Kyiv journalist in the wrong place at the wrong time. He finds himself on a bus at a Russian-controlled checkpoint, and when the area is shelled and the bus destroyed, Volkovsky is one of the few who survive. He also is one of the few who observed that the shelling came from Russian, not Ukrainian, forces.

Through Volkovsky’s observations, readers experience the unhygienic and inhumane cells occupied by both male and female prisoners. “Seven people were sitting and lying on the foam and on the bare floor,” Volkovsky observes. His cellmate, Inna, a beautiful woman accused by Russians of being a Banderite because she plays one on TV, references the art center “Isolation.” Readers who have spent time with Stanislav Aseyev’s books The Torture Camp on Paradise Street and In Isolation: Dispatches from Donbas will very well understand the significance of Inna’s reference.

I survived the basement prisons of the “Luhansk People’s Republic.” Here is what I saw. Part 1

“Isolation” (“Izolyatsia”) refers to the art center and installation which Russians converted to serve as the Ministry of State Security. According to a 2020 Euromaidan Press article, detainees refer to the prison as “a torture chamber, a concentration camp, or even hell.”

Reporter Volkovsky also introduces another aspect of the propaganda war with which Western readers may be unfamiliar – press censorship. Since February 2022, Western audiences have been introduced to the media crackdowns instituted by the Kremlin. In Russia,at the war’s beginning, Putin instituted laws which cracked down on Facebook usage and foreign media access. The Kremlin even forbade Russian citizens from using the word “war.” Lukanov’s novel places a magnifying glass over the treatment of Ukrainian journalists in Russian-controlled Donbas.

Volkovsky acknowledges that Russian authorities beat up Ukrainian journalists and that “The only people they would not touch with almost 100% guarantee were the Russian journalists” because “They considered them supporters.” An August 2022 Reuters article parallels Volkovsky’s fictional experience with real-life ones.

The article highlights the team members of Vchasno, a Donbas-based news agency once dedicated to social activism within the region. Similarly to Lukanov’s fearless character Volkovsky, Vchasno’s team member experienced threats, and two of its male team members accepted the call of duty and went to defend Ukraine.

This is another aspect of the war that Lukanov adeptly captures in his novel–the transition of a journalist into a defender. Volkovsky fully embraces his identity as a war correspondent, and Lukanov portrays this almost poetically in a single paragraph:

“Over several months of war, they had learned how to take pictures while bullets were flying around them. They’d learned how to wear helmets and armored vests. Learned to distinguish between the sounds of explosive shells from BM-21 Grad and the usual cannon. They learned to fall face down on the ground in case of even the smallest danger. They knew how to bandage the wounds. They could send the reports with lots of photos attached in times when there was almost no access to internet.”

The paragraph stands as a commentary about the erasure of one’s previous self. “But war changes a lot of things, including habits,” states Volkovsky. Many Ukrainian defenders and civilians can attest,the war’s emotional and psychological effects have reshaped them in such a way that only those who have experienced the war’s horrors can understand.

As the novel concludes, Volkovsky makes another astute statement, one that resonates globally: “It begins to seem that this war will last forever–that it’s a road to nowhere… that we’ll be killed and nothing can be done about that.” Volkovsky’s words are inherently timeless, as they could pertain to the war in either 2014 or 2022. More significantly, Volkovsky’s words echo sentiments heard frequently from foreign leaders and policymakers. Ukrainians across the globe recognize that the full-scale invasion’s origins lie in eastern Ukraine, on the soil where Europe’s forgotten war unfolded.

However, Ukrainians have proved they are prepared to and willing to defend every inch of Ukrainian soil, despite the high cost. Again, Lukanov perfectly seizes this mentality via Volkovsky’s character. Volkovsky states, “‘Ukrainians now fight for your European values more than the Europeans themselves…They shed their blood for your and our freedom.” Volkovsky also notes, “By the way, what if those aren’t European values anymore but Ukrainian ones?”

Reporter Volkovsky is one of the most necessary Ukrainian novels to emerge in the past nine years. It gives readers a glimpse of the journalistic hurdles Ukrainians like Yuriy Lukanov endure and overcome to bring what’s really happening on the Ukrainian front to a global audience.

Like Maxim Butchenko’s The War Artist, it highlights the familial splits caused by a propaganda powerhouse determined to fracture an entire nation. Similarly to Andrey Kurkov’s Grey Bees, it houses a memorable main character with an authentic voice and an authentic mission. Even more so, Reporter Volkovsky reveals another important message to the world– that because of propaganda’s influence, reality often becomes stranger and more absurd than fiction.

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian American poet and essayist of Rusyn origin. She teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Nicole Yurcaba is a Ukrainian American poet and essayist of Rusyn origin. She teaches poetry workshops for Southern New Hampshire University and is a guest book reviewer for Sage Cigarettes, Tupelo Quarterly, Colorado Review, and The Southern Review of Books.

Related:

- Eleven books to understand Ukraine’s ongoing struggle: a shortlist by Ukrainian politicians

- The rebirth of Ukrainian literature and publishing: famous contemporary authors and new…

- A view of Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution from the square

- 8 Ukrainian book illustrators that will amaze you

- 2017 marked the beginning of Ukraine’s cultural renaissance

- War veteran Illia Titko: “My “blood formula” has now been changed forever!”

- Putin’s war in Ukraine looks very different in Pskov than it does…

- Graphic novels on the Holodomor