As of 28 March, Russia deported more than 400,000 Ukrainians, Ukrainian Ombudsperson Liudmyla Denysova said citing a Russian official. Often, they are denied opportunities to return to Ukraine.

On 24 March, the Mariupol City Council reported that Russian forces started deporting about 15,000 Mariupol residents from the city’s Livoberezhnyi (Left Bank) district to Russia. The invaders, according to the city council, give an ultimatum to Mariupolites to get on buses to Rostov, while denying them evacuation to Ukraine-controlled territory. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) announced its scandalous decision to open an office in Russia’s Rostov-on-Don “in order to improve our work in the Donbas and other parts of Ukraine under control of the Russian armed forces,”

Ukrainian Minister for Temporarily Occupied Territories Iryna Vereshchuk called on the ICRC to obtain lists of Ukrainian nationals forcefully deported from Mariupol and to provide those with the opportunity to return to Ukraine. She says that the Russian troops have forcefully deported 40,000 Ukrainians.

The Ukrainian media project Graty checked the information on the forced deportation, talking to translator Natalia Yavorska (name changed for safety reasons), who went through the process of deportation from Mariupol to Russia but later managed to escape abroad.

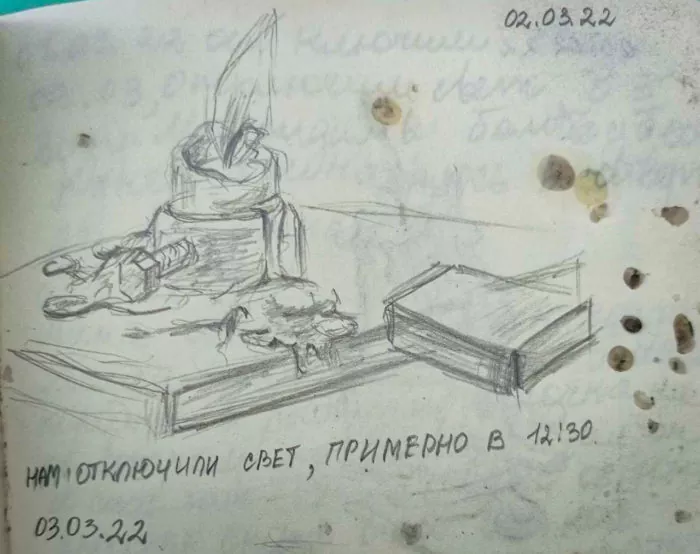

Here we publish the translated excerpts from Natalia’s story related to her deportation. The full story is available in Ukrainian.

How I was forced to “evacuate” to Russia

By March 15, Russian troops had occupied most of our settlement, but hostilities still continued near my home. The Russians walked door to door, came to our shelter saying that everyone should go out as the evacuation of women and children was underway.

Apart from shelter, we had nowhere to go. Several men with large families managed to leave. We were taken to the school in front of the club. This was the first time I had ever gone outside in many days.

It’s a wild feeling when you go down into the shelter with everything completely intact, and then you go out and see that the building in which you were is no more, only the bricks are scattered.

It’s a surreal feeling when instead of the canteen you had frequented while in school, there’s a pile of bricks with textbooks scattered on the floor. There was a Pride of the School stand on the wall with a portrait of my sister, and Russian soldiers near it.

A woman died during the “evacuation” because her heart couldn’t stand it. There was a man who couldn’t move on his own and his wife used to care for him. He was denied evacuation and stayed alone.

They took us to the bombed-out school building, and then took us out of our settlement.

Our settlement had 2,000 people, there were a lot of us. There were about 90 people in our group. They made several journeys to take people out.

The shelter was essentially the only place we could stay in. Most of the people who were with us no longer had houses, they couldn’t hide somewhere in the settlement.

At the exit from our settlement, they put us in the military Ural trucks and took us to the nearest village that they captured a few weeks ago.

There we were lodged at the school for one day. On the next day, they put us on buses and said that we won’t go to Donetsk.

Asked “where are you taking us?” they answered, “To a warm place,” behaving in such a way that we seemingly should have been incredibly grateful to them for “liberating” us from our homes.

They were going to take us to Novoazovsk (an occupied town on the coast of the Azov Sea near the Russian border, – Ed.), but we found out about it later. The drivers from Donetsk were completely disoriented. They had no coordination. Throughout the journey, everyone treats you like a sack of potatoes. The driver, of course, knew where we were going, but everyone was ordered not to give us any information.

Filtration camp

The filtration camp had a tent with a bunch of soldiers. We all were sitting in buses and entered there one by one. First, they photograph you from all sides, apparently for the face recognition system, which is now being introduced in Russia.

Then they take your fingerprints, but the worst thing is that the fingerprints aren’t enough and they even scan your palms from all sides.

Then you are interrogated for “rehabilitation.” They ask you which of your relatives remained in Ukraine, whether you saw the movement of Ukrainian troops, how you feel about Ukrainian politics, how you feel about the government, how you feel about the “Right Sector.”

A long questionnaire to question you, but not harshly. What was the most confusing thing to me was that they take your phone, connect it to a computer for 20 minutes, and download the contact database, but I don’t know if they also download all data and copy the IMEI.

We waited for about 4-5 hours before getting to the filtration camp. Then a few more hours passed. The buses had no toilets. One was in a trench far away. My 70-year-old grandmother is 70 years old twisted her ankle and couldn’t walk normally.

We were taken to the border between the “DNR” [“Donetsk People’s Republic,” Russia’s puppet statelet in eastern Ukraine – Ed] and Russia. We spent the whole night in the bus in very uncomfortable conditions.

The Russian Federation begins with searches. They selectively interrogate women and men. There were fewer women, but I was among the unlucky.

It was f*cked, because after you spent two weeks in a basement under shelling, the first person you meet is a Russian FSB officer. He drove me into very strong paranoid feelings.

I have artistic texts related to Ukraine, war, I don’t think they are super noticeable. But still, I had paranoia. I was scared, and he asked me if I knew about the movement of Ukrainian troops, what I knew about Ukrainian soldiers, and everything else.

I thought about the tactics of the FSB hooks: asking one question, joking about something, then asking the same question again to find out whether I lied or not. But in fact, most of the time we discussed my relationships. The FSB officer was most interested in this issue.

All my social media accounts are linked to a Ukrainian phone number. I was confused at first, said the wrong number on purpose, but it was still silly. They wrote down my phone numbers, asked a lot of questions, and said that I was “too mysterious.”

In short, we were released. I tried to leave with my family – my grandmother, mother, brother, aunt with her children – but it wasn’t allowed – you can’t just go about your business.

Escape

We were taken by bus to Taganrog (a city in Russia’s Rostov Oblast, – Ed.). There, we were told that they send everyone to the city of Vladimir by train.

From Taganrog, we got to Rostov. We were my grandmother, mother, brother, and I. The other relative couldn’t be taken out because she left her passport at home and had only its photo. Now we are trying to take them out through the embassy of Ukraine into other countries.

We went to Rostov and stayed overnight with relatives living there. This is also a crazy situation. They are very hospitable but completely brainwashed by Russian propaganda. They say: don’t worry, you will return to Mariupol by fall, everything will be cleaned up there, and everything will be fine.

Besieged Mariupol: How Russia obliterated a nearly half-million city in one month (photos)

There’s quite a bit of Russian military equipment in Rostov. The city lives as if a war’s going on there. When we were traveling on the Rostov-Moscow train, I had a very strange feeling when the whole train was discussing Mariupol. They said that bioweapons were being developed in Mariupol to destroy the reproductive system of Russian women. The feeling was like falling into a collective dream.

I called friends who stayed in the refugee camps. They received Russian SIM cards. We want to help everyone get out somehow. They have food and housing there, but no tickets. I think they have been displaced only to make a picture for the propaganda of how Russia evacuated people.

I mean, they deport people from Mariupol, forcibly taking them first to the occupied territory, then to Russia. There are camps where they can live, where there is communication and even Russian SIM cards. By summer, they have to find a job so that they earn their own money. Only low wages are available.

In Vladimir, the conditions vary. Some are lucky, some are not. They get a one-time payout of 10,000 rubles (about $100 as of 27 March 2022, – Ed.), but some people can’t receive them. If they receive temporary asylum instead of refugee status, they can leave at any time. But the situation with men is unclear. Because Ukrainian men may not be allowed to leave the Russian Federation.

Everyone I contacted has been in a state of prostration, everyone has health problems. Many grandmothers have mental problems, and it’s unclear how to organize their return. They have no homes left in Mariupol and the very idea of going somewhere is very difficult for them.

But it is even more difficult to live in a place that completely denies your experience. I think it’s very scary when you know the truth of what has happened, but everyone lives in some kind of dream, and you have to guess what this dream is about.

When they were taking everyone to Vladimir, we refused asylum. We did so but could only stay in Russia for 15 days without registration, during which you have to leave. The problem arose, for example, among those who had no money. Russian relatives would like to transfer the money, but there is no destination they need to make the transfer. Some manage to find some locals, transfer the money to them, and then the locals bring cash to the camp.

From Rostov, we left for Moscow, and from there for St. Petersburg. We stayed there for three days. On 22 March, we went abroad.

A grandfather remained in our settlement near Mariupol. His grandma is very sorry that she left. She wanted to stay with him, but everything was so fast and messy that she couldn’t decide. Her son remained. I am worried that he’ll be given a “DNR passport” and forced to fight.

“The last week was pure horror and hell,” evacuee from besieged Mariupol recalls

Also, my grandparents who used to cook for us remain in Mariupol. We even managed to send the evacuation vehicles there, but they eventually refused to go. They believe that this is their land. All the houses around my grandfather have been bombed out. He stayed in his house with shattered windows because he believes that this is his place and no one has the right to disturb him.

I managed to get in touch with my grandfather. There is heavy looting in the villages, the Russian military just gets drunk and shoots at the ceiling of houses. They just get drunk and shoot.

Many women are in shelters with children. Many women run to the destroyed houses under fire, trying to find some food. And the houses have already been occupied by Russian soldiers. This is a terrible situation, a completely different experience and I don’t know anything about it.

Read also:

- I was inside when the Russians bombed Mariupol drama theater: survivor’s story

- “I’m sure I’ll die soon. It’s a matter of days” – resident of besieged Mariupol

- Besieged Mariupol: How Russia obliterated a nearly half-million city in one month

- “Mariupol people melt snow, drink water from heating mains”: besieged city faces total destruction

- “The last week was pure horror and hell,” evacuee from besieged Mariupol recalls

- Martyred city of Mariupol wiped out of existence by Russia’s incessant shelling