Human losses are justly viewed as the greatest tragedy of any war, the current war in Ukraine being no exclusion. One may argue, why should we distract our attention to such things as cultural heritage during wartime? Can we even use “culture” and “war” in the same sentence?

History, though, has proven that we cannot afford to ignore the protection of cultural heritage during warfare.

Our cultural heritage is unique and irreplaceable. Tangible items of cultural property are witnesses of the past that show us our true history and preserve our memory of it. Cultural heritage appeals to strong emotions that evoke our identity, awareness, and sense of belonging to a community.

It took a long time for the world to recognize that no matter where cultural property comes from, it belongs to “all mankind” and its disappearance, according to UNESCO, is “a harmful impoverishment of the heritage of all the nations of the world.”

Targeting cultural heritage during warfare is a way “to destroy and overtake a society by erasing its memory.”

Protection of cultural property under international law

The first attempts to legally protect cultural property during war were made in the 19th century. The worst lesson, however, was learned from WWII, Luftwaffe’s bombing of Valetta’s Royal Opera House being just one of the examples.

By definition, any item of cultural property is a civilian object protected by general rules of warfare. However, given the fragility of cultural property in the face of war, the international community, including Russia, adopted the 1954 Hague Convention to protect cultural property during wartime.

In addition, the protection of cultural heritage became a key focus of specialized international organizations, UNESCO being the most widely known.

It’s worth saying that cultural heritage comes in all forms and shapes. Depending on the international treaty, the law offers protection to different cultural objects.

The mentioned 1954 Hague Convention covers such items of culture as monuments of architecture, art, or history; archaeological sites; groups of buildings of historical or artistic interest; works of art, manuscripts, books, etc. Protection is also granted to buildings and places where cultural property is housed or sheltered (museums, libraries, archives) and centers containing cultural property in large amounts.

The Russian Army’s destruction of cultural property in Ukraine

In the last week of the large-scale war against Ukraine, Putin has already gained fame as “Hitler of the 21st century.” Similar to the Nazi attacks on cultural items, Russian bombs target now not only the lives of Ukrainian militaries and civilians, objects of critical infrastructure, and houses, but also the cultural heritage of Ukraine.

The Ukrainian culture inherited from past generations is being brutally destroyed right now, under the auspices of Putin’s “denazification” plan. During the last week, Ukraine has already suffered irreparable losses.

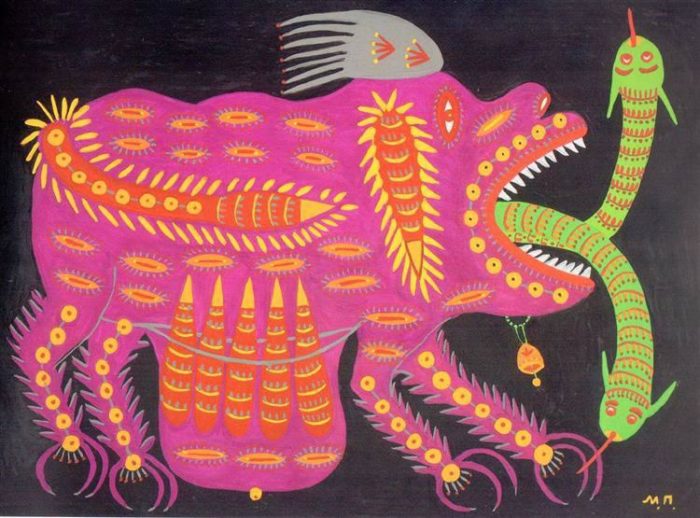

On 28 February, Russian trhttps://twitter.com/DespoilerofH/status/1501889028911775746oops targeted the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, which stored paintings of Ukrainian artist Mariya Prymachenko, an icon of naive art. While the building of the museum was destroyed in the blaze, the paintings, or at least their portion, were reported to be miraculously saved by the locals. Even though the paintings are now stored in private houses of locals, that, in any case, puts them at risk given the attacks are still ongoing.

https://twitter.com/DespoilerofH/status/1501889028911775746

With a missile strike, Russian invaders destroyed the Chernihiv Regional Youth Center, a monument of architecture, constructed in 1939.

Also damaged by Russian occupation troops is the Round yard in Trostianets (Sumy Oblast), the oldest public building in the north-eastern part of Ukraine created in the XVIII century.

Chernihiv after Russian airstrikes. Video by Suspilne Chernihiv

Ukrainian Jews were outraged when a missile strike on Kyiv’s TV tower damaged the Holocaust memorial, located on the grounds of Babyn Yar, a location where Nazis murdered roughly 100,000 people, most of them Jews, during the Holocaust.

“To the world: what is the point of saying ‘never again’ for 80 years, if the world stays silent when a bomb drops on the same site of Babyn Yar? At least 5 killed. History repeating,” President of Ukraine Zelenskyy tweeted.

A real “denazification” as it is.

It is no wonder that the Kruty Heroes Memorial was also “noticed” by Russia. The Russian army shelled a symbol of Ukraine’s heroic struggle against Russian Bolsheviks who attacked Kyiv in 1918.

As a result of shelling by Russian troops, the Dormition Cathedral, the oldest orthodox church of Kharkiv constructed in the VIII century, was damaged.

We wish this list of damaged cultural heritage objects stops growing. Unfortunately, new risks exist. As reported by the Ukrainian Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine Oleksandr Tkachenko, Kyiv’s Saint Sophia Cathedral, created in the XI century and inscribed on the World Heritage List, is planned to be destroyed.

“Any damage to or destruction of the cathedral caused by Russia will be an irreparable loss for all mankind,” he said.

Lviv’s Historic Center is also included in the World Heritage List. To protect it from destruction, Lviv authorities are moving sculptures and other objects to the shelters. Those sculptures that cannot be easily removed are covered with protective materials.

Do Russian attacks on Ukrainian cultural property constitute war crimes?

International law prohibits attacks made without due regard to their potential targets. Considering the great importance of cultural heritage for all the peoples of the world, cultural property bears protected status not only under the 1954 Hague Convention but also the 1949 Geneva Conventions (codification of international humanitarian law) as a civilian object.

It is of no surprise that the armed conflict always entails risks that civilian objects, including cultural property, might end up damaged or even destroyed. If the cultural property is harmed unintentionally and incidentally, this would not be in and of itself be punishable.

The situation is, however, completely different if the cultural property is damaged on purpose.

Such actions constitute war crimes. Not only the direct perpetrators of those crimes but also their commanders and even high state officials shall bear personal criminal responsibility before the national courts and international tribunals. One of such tribunals authorized to investigate and try for international crimes is the International Criminal Court (ICC) established under the Rome Statute. The Statute defines the following types of war crimes in relation to cultural property:

- Intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion, education, art purposes, historic monuments, provided they are not military objectives (Article 8(2)(b)(ix) of the Statute);

- Intentionally directing attacks against civilian objects, that is, objects which are not military objectives (Article 8(2)(b)(ii) of the Statute);

- Intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause damage to civilian objects which would be clearly excessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall military advantage anticipated (Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Statute);

- Extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly (Article 8(2)(a)(iv) of the Statute).

That said, for determining whether the destruction of cultural property constitutes a war crime, it is important to understand three main concepts – military objective, military necessity, and military advantage:

- Military objective. A specific object becomes military objective if it makes an effective contribution to the military action and its destruction offers a definite military advantage. As a general rule, the following objects constitute legitimate military objectives: military fortifications, camps, units, aircraft, warships, repair facilities, etc. However, civilian object may also become a military objective if it is used for military purposes contributing to military action. For instance, cultural property may lose its protected status if it is used as a sniper’s nest.

- Military necessity. Military necessity implies that the measures are required to secure the ends of war – weakening the military capacity of the opponent.

- Military advantage. This implies certain gain that the party to the conflict anticipates getting through the attack. Such advantage shall be of tactical nature – relatively close and substantial; long-term goals – such as winning the war in general – should be disregarded.

To date, there have been several recorded instances of Russia’s attacks against Ukrainian cultural property.

Based on the circumstances surrounding the attack, the mentioned cultural property could not constitute a military objective (it was not used by the Ukrainian army), its destruction was not urged by military necessity (it remains unclear how their destruction would help Russia to weaken the military capacity of the Ukrainian Armed Forces), the destruction did not pose any military advantage (it is unclear how their destruction could help Russian forces to facilitate specific military operations).

That said, there are substantial grounds to believe that Russia’s actions in respect to Ukrainian cultural property constitute war crimes within the meaning of the Rome Statute:

- either directing attacks against the cultural property (Article 8(2)(b)(ix) of the Statute) or

- launching an attack with knowledge that such property would be excessively damaged (Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Statute).

Even if the attack was not targeted against the cultural property directly, it is still prohibited to shoot the vicinity if this may inflict unjustified damage.

In the past, people that destroyed cultural heritage were charged with committing war crimes.

For instance, Milan Martić, leader of so-called ‘Martić’s police’ in the former Yugoslavia, was found guilty of destruction by a tank of the Assumption of the Virgin church in the center of Škabrnja, Croatia, conducted by its inferiors. He was found guilty of 18 counts overall and sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment.

Currently, the ICC prosecutor initiated an investigation of Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine. Hopefully, all the facts of Russian outrages in Ukraine, including with respect to cultural heritage, will be documented and investigated, while all the responsible, including the higher Russian officials, will face charges.

This, however, will take time. But should the international community wait until the cultural heritage of Ukrainians and the whole world is being erased by missiles and bombs?

Something has to be done before it`s too late.

What can the international community do to stop Russia from further destruction of Ukrainian and world heritage?

On 27 February 2022, responding to the threat of destroying Kyiv’s Saint Sophia Cathedral, Mr. Tkachenko asked UNESCO to deprive Russia of the status of UNESCO member as well as to change the host country of the 45th session of the World Heritage Committee.

On 3 March 2022, only after the UNGA Resolution denouncing Russia’s invasion, UNESCO demanded Russia refrain from “inflicting damage to cultural property” and condemned “all attacks and damage to cultural heritage in all its forms in Ukraine.”

UNESCO also expressed deep concerns related to damages incurred by the cities of Kharkiv, Chernihiv, as well as damages to the paintings of Mariya Primachenko, with whose anniversary UNESCO was associated in 2009.

On 15 March 2022, the UNESCO Executive Board will hold a Special Session “to examine the impact and consequences of the current situation in Ukraine in all aspects of UNESCO’s mandate.” Russia’s invasion into Ukraine and its horrible impact on the Ukrainian cultural heritage also caused public condemnation by the International Council of Museums, the World’s Monument Fund, the European Voice of Civil Society committed to Cultural Heritage.

Solidarity with Ukraine was also declared by the global NGOs and art institutions. Getty Trust, the world’s biggest philanthropic foundation, stated:

“What is taking place in Ukraine is a tragedy of monumental proportions”

However, today Ukraine needs more than voicing concerns by the international community.

While some measures are already on the way, there are still available means to stop, or at least narrow the scale of, Russian attacks towards Ukrainian cultural heritage:

- imposing sanctions on Russia by States parties to the Hague Convention (Article 28 of the Hague Convention);

- conducting the conciliation procedure by the Protecting Powers responsible for the execution of the Hague Convention (Article 22 of the Hague Convention);

- calling UNESCO for assistance in the protection of cultural heritage (Article 23 of the Hague Convention);

- excluding Russia from international organizations, including UNESCO, the International Council of Museums, the European Voice of Civil Society committed to Cultural Heritage;

- reporting evidence of attacks on Ukrainian cultural property to the International Criminal Court Prosecutor Karim A.A. Khan QC via: [email protected];

- requesting MPs and governmental bodies to shelter the Ukrainian sky, to provide anti-aircraft warfare to stop Russian bombings.

Mr. Oleksandr Tkachenko together with hundreds of organizations and thousands of cultural activists have already asked the international cultural community to impose sanctions on Russia, including:

- canceling all projects that involve Russia (including ones funded by Russia);

- banning representatives of Russia from participating in international competitions (e.g., the Eurovision ban), exhibitions, forums, music and film festivals, and other cultural events;

- removing Russian citizens from the supervisory boards and cultural partnerships, canceling sponsorships, and withdrawing organizational support;

- eliminating coverage of Russian culture in the media.

Stopping further destruction of Ukrainian cultural property depends only on Putin’s choice. Still, this choice may be influenced by mentioned above mechanisms.

World leaders must remember – preservation of Ukrainian cultural property at these trying times is a responsibility of the whole international community as

“any damage to cultural property, irrespective of the people it belongs to, is a damage to the cultural heritage of all humanity.”’– Preamble of the Hague Convention.

Related:

- Russia continues to plunder and destroy Crimea’s cultural heritage: 150 crimes documented by experts

- Bombing hospitals and maternity wards in Ukraine: a brutal „innovation“ of Russian occupying forces

- Ukraine vs Russia at the ICJ: It is not Ukraine commiting genocide, but Russia committing war crimes in Ukraine

Hanna Yareha is a legal counsel at SoftServe and a moot court participant with a solid background in public international law

Kateryna Ilieva works in the dispute resolution practice of AEQUO law firm and participated in moot courts, such as Jessup and FDI Moot.

Nataliia Savula is an international arbitration associate at Asters Law Firm with strong public international law and international investment law background.

Nataliia Savula is an international arbitration associate at Asters Law Firm with strong public international law and international investment law background.