At the same time, Russia's cyberattacks on Ukraine after the full-scale invasion are surprisingly meager.

On 1 March 2022, the Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine Mychaylo Fedorov, who previously launched the IT Army of Ukraine, wrote:

“If in the beginning we constrained many powerful cyberattacks, mainly due to the long preparation of Russia in advance, now, thanks to the common spirit of Ukrainians for freedom, we have moved to a confident offensive.”

Soon after the first cyberattacks on Russia by Anonymous, an international hacker activist group – the IT army of Ukraine -- was launched. While there have been a number of successful cyber attacks on Russia, Russia is much less active in cyber attacks than was expected. There are a number of possible reasons.

Anonymous declares cyberwar against the Russian government on the very day of the invasion

On 24 February, the day Russia invaded Ukraine, Anonymous, one of the largest and most widely-known hacker groups, declared it is “officially in cyberwar against the Russian government.”

The damage did not take long to be felt. The very next day, 25 February, Anonymous breached the Russian Ministry of Defence’s database and posted it online for Ukraine and the world to see.

The Anonymous mask, known from the novel and movies V (Vendetta), was first donned by England’s famous rebel Guy Fawkes, a conspirator in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot.

According to Anonymous, on 25 February they took down 1,500 websites of the Russian and Belarusian governments, including the website of the Ministry of Defense, the Kremlin, and the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service.

On 2 March, the group reported that one of their affiliated hacking splinter groups had shut down the Russian space agency Roscosmos which is responsible for Russia’s control over Russian spy satellites. It also intercepted several streams of Russian military communication.

Russian TV channels were also attacked, playing Ukrainian music and displaying national symbols. The attack brought uncensored news of the conflict from news sources outside Russia. Russia Today, the state-backed news service, was also taken down with DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks. This type of attack works by overwhelming a target website with fake traffic.

On 28 February, Russian media sites, including TASS and Kommersant, were blanked out to display “5,300,” the number of Russian troops killed by Ukraine’s army according to official data.

That same day, Anonymous addressed Russians in an ominous tweet.

“Understand that Putin has invaded a sovereign nation and the whole world is outraged. We know it’s risky to stand up to him, but if you don’t, then who will?”

“DDoS alone will not bring down a regime,” a German Anonymous splinter group posted in a blog. “[But Putin] who is using hacker squads and troll armies against Western democracies, is getting a sip of his own bitter medicine. [The intention is to] keep the Russian IT apparatus busy and to provide Putin's hacker troops ... with defensive work so that they cannot do anything in Ukraine or the West. Obtaining information is also an important point and you just don't see a lot of what activists are currently doing.”

It is also important to note that Anonymous activity is highly decentralized, so it is difficult to definitively attribute all these attacks to Anonymous. However, as Jamie Collier, a consultant at US cybersecurity firm Mandiant, explained about recent Anonymous activity:

“It can be difficult to directly tie this activity to Anonymous, as targeted entities will likely be reluctant to publish related technical data. However, the Anonymous collective has a track record of conducting this sort of activity and it is very much in line with their capabilities.”

There are examples of other hacker groups launching cyber attacks. One is the Belarus group, Cyber Partisans. When the self-proclaimed president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenka joined Russia’s invasion, the Cyber Partisans attacked the Belarus Railway Service website to slow down the movement of the country’s troops. As of 2 March, the Cyber Partisans report that the attack on the railway continues.

26 February: Ukraine launches IT army

On 26 February, the Minister of Digital Transformations of Ukraine Mychaylo Fedorov announced on Twitter:

“We are creating an IT army. We need digital talents. All operational tasks will be given here: https://t.me/itarmyofurraine. There will be tasks for everyone. We continue to fight on the cyber front. The first task is on the channel for cyber specialists."

Fedorov then posted on Facebook:

“We have a lot of talented Ukrainians in the digital sphere: developers, cyber specialists, designers, copywriters, marketers …”

Hundreds of people started joining the IT army immediately after this announcement – as of 2 March, there are more than 270,000 subscribers in the IT army chat. These subscribers are not only IT specialists but include people who are helping to inform the citizens of Russia and Belarus about the true situation in Ukraine. All media in Russia and Belarus is heavily controlled – essentially propaganda.

The IT army took down a technology used by one of Russia’s biggest banks, Sberbank. The main Russian money master – the Moscow Exchange – came down at the start of the workweek, 28 February.

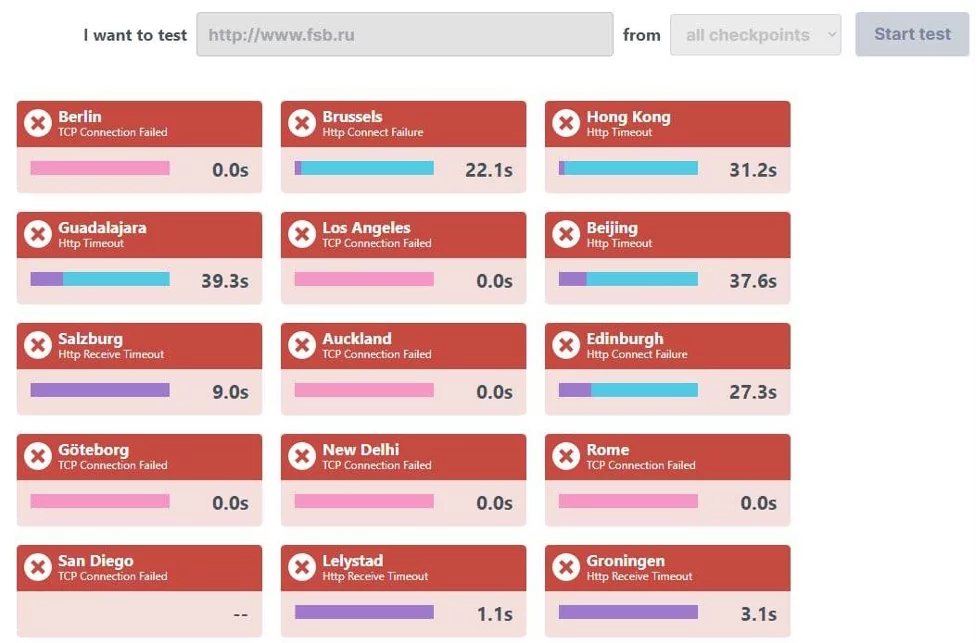

There have been attacks on Russian official websites, as well as the web resources of Belarus. The website of Russia's Investigative Committee, the FSB, Sberbank, and other government and critical information systems both for Russia and Belarus have been taken down.

Among the known blocked resources are

- sberbank.ru

- vsrf.ru

- scrf.gov.ru

- kremlin.ru

- radiobelarus.by

- rec.gov.by

- sb.by

- belarus.by

- belta.by

- tvr.by

“For a country that’s facing an existential threat like Ukraine, it’s really not surprising that this sort of call would go out and that some citizens would respond … Part of it is also a signaling exercise. It’s signaling a level of commitment across the country of Ukraine to resisting what the Russians are doing,” said J. Michael Daniel, head of the industry group Cyber Threat Alliance and former White House cyber coordinator for President Barack Obama

On 24 February, an attack was made on information resources and the main contractor of all state projects in information technology in Russia, Systematics. The owner of Systematics is Putin's “right-hand” Dmitry Medvedev. The evolution of Systematics included the automated electoral system Elections that were used to legitimize Putin’s regime for years. It too was disabled.

“So Russians will now vote the old way, on paper,” Nikonov suggested.

Nikonov added that other developments of Systematics were disabled – significantly the electronic document management systems of Russia in the territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, as well as in the so-called "DNR" and "LNR":

“All files from the servers have been downloaded and already transferred to our law enforcement agencies for analysis and inclusion in the materials of criminal cases against officials of the aggressor country, as well as leaders of the so-called "D/LNR" and their henchmen. Thanks to these materials, Ukrainian law enforcement officers now know for sure every scumbag who took part in the annexation of Crimea and in terrorist acts in eastern Ukraine.”

In addition, on 25 February, the management system of the Federal Treasury of the Russian Federation was destroyed, which led to disruption of the basic mechanisms and instruments of financing the army, law enforcement agencies, executive authorities, and state-owned enterprises.

What about Russian attacks?

According to a Ukrainian senior cyber official, the government was prepared for a Russian invasion cyber attack for days. All sensitive data was to be transferred on 22 February out of Kyiv, should Russian troops move to seize the capital.

However, during the week of the Russian invasion, as an article in the Economist put it, cyber attacks by Russian hackers were “conspicuous by their absence.”

The article mentioned previous successful Russian attacks in Ukraine. In 2015, Russian hackers managed to knock out power for some 230,000 customers in the west of Ukraine. In 2017, the Russian attack dubbed “NotPetia'' disrupted Ukrainian airports, railways, and banks. This suggests that Russia has a vast capacity for cyberattacks. According to an analysis of leaked bitcoin addresses, Conti ransomware, which is associated with Russia’s intelligence service, has ratched up at least $2.7 billion since its inception in 2017.

Russia also spreads propaganda through the internet. For example, as of 1 March, the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine has been warning Ukrainians about large-scale Russian disinformation campaigns using fake news and videos about an impending capitulation by Ukraine. During 1-2 March, people in different regions of Ukraine reported frequent disruptions in their internet connection.

Experts agree that Russia’s cyberattacks are fewer than were expected, although the interpretations differ. Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Mark Warner said 28 February:

“I’ve been pleasantly surprised so far... that Russia has not launched more major cyber attacks against Ukraine. Do I expect Russia to up its game on cyber? Absolutely.”

The Economist article suggests that one reason attacks are not occurring is that Ukrainian digital defenses are stronger than presumed. It is also possible that decentralized hacker group attacks, like those of Anonymous, take time for Russian hackers to resolve. As the Economist author concludes:

“One of the problems with cyber attacks is that it is often hard to be sure.”

Related:

- Ukrainian official sites under massive cyberattack with a Russian trace (January 2022)

- Ukraine’s Security Service says it neutralized over 2,000 cyberattacks in 2021

- Is Ukraine ready for future cyberattacks? Don’t hold your breath, experts say (2022)

- Strengthening the security resilience of Ukraine: military, energy, cyber