However, a close review of the international experience reveals there is no magic bullet. Ukraine will have to find its own path – but it makes sense to learn from the successes and failures of other countries.

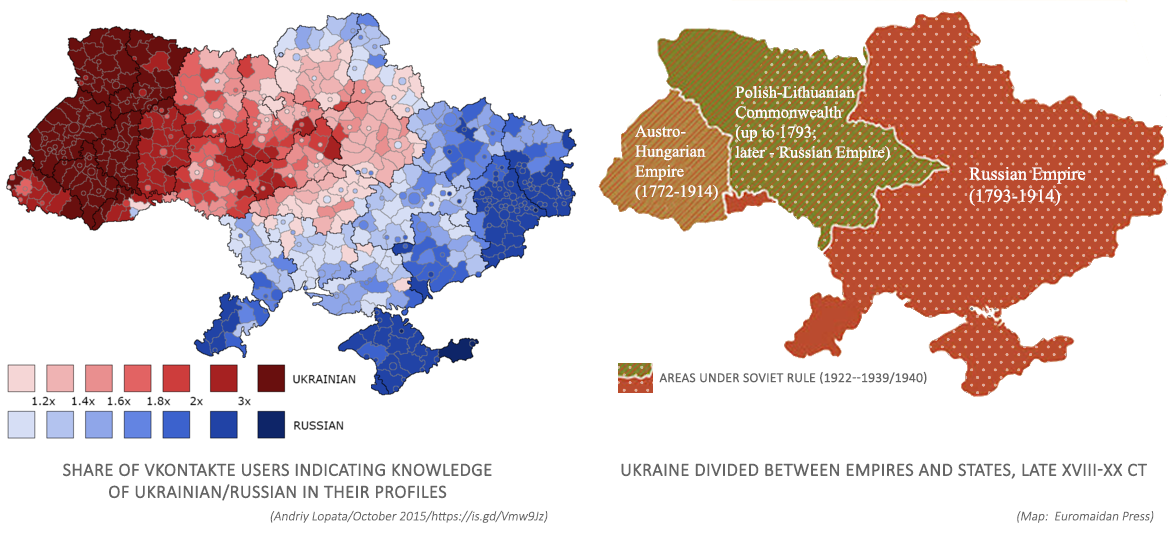

Language policies have been a matter of contention - and sometimes confrontation - in Ukraine since the early years of independence, due to both the dissimilar preferences of domestic political actors and the interference of Russia and other neighboring states, often supported by international organizations preoccupied with minority rights.

One contentious point concerns the desirability of adopting the policies of some Western countries, whether markedly multilingual or supposedly unilingual.

Both Ukrainian politicians and Western experts have often referred to foreign experiences as guidance for Ukrainian policymaking, and many citizens have accepted this reasoning.

On the one hand, many believe that Ukraine with its two main languages is rather similar to the largely bilingual countries like Belgium or Finland and, therefore, it should follow their example and grant official status to both Ukrainian and Russian. Some proponents of multilingual policies even look to the example of Switzerland with its four official languages; in effect, they believe that the more languages enjoy official status, the better the rights of citizens are safeguarded.

On the other hand, many people argue that Ukraine should rather behave like France or the Baltic states which resolutely assert the primacy of their national languages despite the challenges of globalization and, in the latter case, the legacy of imperial Russification. In this thinking, multilingualism is a danger to the national language, distinctiveness, and, ultimately, independence.

Multilingual policies are not always as successful as they seem

The case in point is Belgium where the policies to reconcile the interests of the two main language communities have nearly torn the state apart, but which many people in Ukraine consider as good an example of official multilingualism as the remarkably stable Switzerland.

Moreover, many of the praised countries are not as harmoniously multilingual or overwhelmingly unilingual as they seem from afar.

In Canada, for example, English and French have an equal status only in federal institutions, while all but one provinces are officially monolingual with rather little accommodation of the language needs of speakers of the other federal language (let alone other languages spoken by sizable groups of citizens). And while French has for the last half-century become much more used and respected in Quebec, it continues to wane in most other parts of the country.

Most importantly, language (or any other) policies succeed or fail in a particular social and political context, and those seeking to adopt a certain policy in another country should first check whether its current context is similar enough to the one in which it was originally implemented.

It makes little sense to try and adopt the Swiss model of territorially delineated multilingualism because it developed many centuries ago under the conditions of a loose confederation of cantons each of which was free to pursue its own language policies with one local language (in today’s terms, a dialect).

Similarly, one cannot understand the relative stability of the relations between the two language groups in Finland and the prolonged confrontation in Belgium without taking into account their dissimilar contexts in the formative years of the two states, namely the generous treatment of the Swedish-speaking minority in the former case and the flagrant insensitivity of the French-speaking elites to the needs of the Flemish masses in the latter.

And it is important to understand that the majority could assert the primacy of its language more resolutely in Quebec than in Catalonia not only because of its stronger numerical predominance but also because Canada is a federation with vast powers of the provinces and Spain is a unitary state where the center can stifle the autonomies’ initiative in the language or any other domain.

Language protection: what Ukraine can learn from three European countries

Finally, the tacit assumption that only Western experiences can provide relevant examples for Ukraine’s language policy is certainly misguided. Like in many other countries across the globe, people in Ukraine tend to see the prosperous and democratic West as the best example of everything and are reluctant to learn from the less advanced (for many, less “civilized”) parts of the world. Similarly, many westerners suggest that the transplantation of a Western model is sure to solve Ukraine’s language issue.

Learning from postcolonial countries

However, language policies of the postcolonial countries of Asia and Africa can teach Ukrainians about challenges the newly independent states face as they try to promote indigenous languages in a context of nation-building and globalization, with the former colonial languages enjoying wider currency and higher prestige due to both the past imposition and the current opportunities they provide. This context is certainly closer to the contemporary Ukrainian situation than that of the long-established multilingualism or the largely unchallenged predominance of the respective national languages in the West. And while the new states have less money than the old Western ones to implement their preferred policies, they are less constrained by democratic institutions in introducing certain local language(s) or maintaining the dominance of the colonial one.

As the borders between colonial territories in Africa and Asia were drawn with little regard to the ethnolinguistic composition of the population, many of the newly-independent states turned out to be much more multilingual than Ukraine or other post-Soviet countries. And since the British and French colonial rulers were less willing to teach and use local languages than were the Soviet authorities (for all their promotion of Russian), Ukrainian is now better known and more readily accepted as a legitimate language of various social domains than are most of the indigenous languages in the post-colonial world.

All these considerations inform my analysis of language policies across the globe in the recently published book Movna polityka v bahatomovnykh kraïnakh: Zakordonnyi dosvid ta ioho prydatnist’ dlia Ukraïny [Language policy in multilingual countries: Foreign experiences and their applicability to Ukraine; Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2021].

I examine not only officially multilingual countries such as Switzerland or Finland but also those where states insist on being unilingual despite society’s multilingualism, as in France or the US. Moreover, my analysis is not limited to Western (European and North American) countries but also includes a number of post-Soviet and postcolonial cases from Latvia and Kazakhstan to South Africa and Algeria.

In each case, I outline the current legislative arrangements and practices in various domains, then examine their historical origins, and conclude with a discussion of current challenges and an evaluation of the measure of success of the chosen policies. My evaluation distinguishes between different normative goals language policies can pursue, namely social stability, national unity, the protection of language rights, and the preservations of languages.

For example, the promotion of language rights of Dutch-speakers in Belgium and French-speakers in Canada brought these countries to the brink of breakup, while in Singapore and Indonesia the assertion of national unity based on one language had a detrimental effect on the knowledge and use of other languages.

No less instructive are experiences, however dissimilar, of Ireland and South Africa, where the state’s promotion of indigenous languages have proven unsuccessful first and foremost because of the willingness of citizens to learn and use English which they perceived as the main language of opportunities.

Ukraine will have to find its own path

The book’s final chapter discusses lessons that can be drawn from these foreign experiences for the language policy of Ukraine. I compare the examined countries to Ukraine on various dimensions of the sociolinguistic and political situation.

To put it simply, most countries are clearly different from Ukraine in terms of the number, relative sizes, and/or geographical distribution of their main language groups, while those that are rather similar in demographic terms tend to have dissimilar political characteristics such as the federal system or an undemocratic regime.

Language policies that could be successful in Ukraine

Nevertheless, I identify some policies that proved successful under rather similar conditions and thus can be expected to yield comparable results in Ukraine.

Most importantly, several countries such as Belgium, Canada, Spain, and Latvia experienced a radical change in the relative powers of the largest language groups, whereby speakers of the formerly discriminated language took advantage of the democratic rule to launch policies giving that language an equal or even preferential treatment.

Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

In all these cases, the formerly dominant group more or less vehemently protested, to the detriment of political stability and national unity, but the group asserting its rights did not consider that too high a price to pay.

In Ukraine, a heated intergroup conflict is unlikely as the boundary between the speakers of the two main languages is porous, and most people primarily relying on Russian in everyday life recognize the value of Ukrainian as the national language, particularly important at the time of war.

Therefore, the opposition to the introduction of Ukrainian as the main language of those domains previously dominated by Russian will manifest itself not so much in open protest as in covert sabotage, the continued adherence to the accustomed language to an extent possible.

This is why it is so important to present the promotion of Ukrainian as intended to give its speakers the same opportunities as those traditionally enjoyed by speakers of Russian and explain that it means, among other things, that people providing services in various public and private establishments must be able and willing to use the state language in communication with customers, at least those signaling their preference for that language.

Services in Ukrainian by default: new phase of language law sparks debate

In conclusion, I would like to reiterate the falsity of the widespread belief in the possibility and desirability of the adoption in Ukraine of certain policies that have proven successful in some foreign countries, or so it seems from afar.

Policies succeed or fail in particular social contexts, and the Ukrainian context is clearly different from those of foreign countries, whether officially monolingual or apparently unilingual, whose language policies many in Ukraine consider to be appealing examples.

Ukraine will need to find its own way, yet its policymakers should take into account the foreign experiences which could teach them what policies are likely to succeed and what is doomed to fail.

Volodymyr Kulyk is a Head Research Fellow at the Institute of Political and Ethnic Studies in Kyiv. He has also taught at Columbia, Stanford, and Yale Universities, Kyiv Mohyla Academy, and Ukrainian Catholic University as well as having research fellowships at Harvard, Stanford, University College London, University of Alberta, Woodrow Wilson Center, and other Western scholarly institutions. His research fields include the politics of language, memory, and identity as well as political and media discourse in contemporary Ukraine as well as language policies in multilingual countries across the world. He is the author of four books, the latest of which is"Multilingual Countries: Foreign Experience and Its Relevance to Ukraine."

Related:

- Language protection: what Ukraine can learn from three European countries

- Ukraine’s European heritage is in its language’s DNA

- Why Ukraine’s language law is more relevant than ever

- Ukrainian language slowly yet steadily displaces Russian in Ukraine

- Ukraine adopts law expanding scope of Ukrainian language

- A short guide to the linguicide of the Ukrainian language | Infographics

- Ukrainian translations, Russian oppression, and soft power

- Ukrainian writer & publisher: Language is the most important marker of national identity

- Experts weigh in on Ukraine’s hotly debated new minority language policy

- Services in Ukrainian by default: new phase of language law sparks debate

- Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

- Elle magazine switches from Russian to Ukrainian