If Instagram, YouTube, and other social media had existed in the 1930s, Sofiya Yablonska would have gathered the largest number of followers and become an instant hit as a travel blogger. This spectacular adventuress would have posted instant travel blogs and easily captured a global audience with her incredible tales and photos.

Sofiya was a fascinating figure – she was exceptional, fearless, a strong woman who followed her calling and was not afraid to be different.

Sofiya Yablonska was an inspired Ukrainian travel blogger, cinematographer and photographer, who traveled around the world, lived in China for many years, and died in a tragic car accident in France. In Southeast Asia, she nearly died from the bite of a banana viper, a malaria mosquito, and the juice of a poisonous orchid; in Laos, she hunted tigers, lived with local tribes on Bora Bora for several months, was received by the last queen of Tahiti, fled the prince of Thailand who wanted to marry her and attended the wedding of a Vietnamese prince. Her notes, books, and travelogues are interesting and unique, especially because they are about countries and customs that no longer exist.

A Ukrainian country girl in Paris

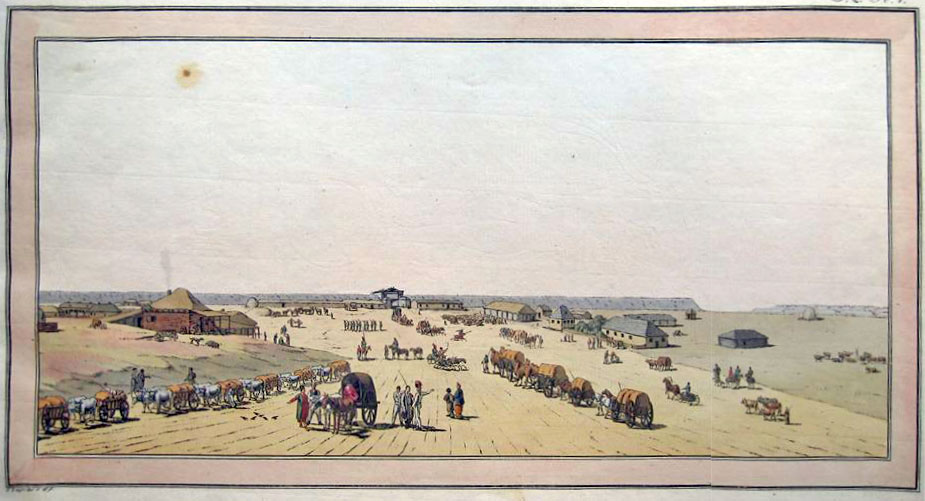

Sofiya Yablonska was born in a family of priests in the village of Hermaniv (today’s Tarasivka), in the Habsburg Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria on May 15, 1907. When the Russian Imperial army withdrew from Galicia (Halychyna), her Russophile father took the family to Taganrog in southern Russia where they lived for six years, and where Sofiya attended drama classes and a commercial school. Disillusioned with the Soviet regime, the family returned to western Ukraine in 1921, namely to Ternopil where Sofiya studied bookkeeping, sewing, and drama at a gymnasium.

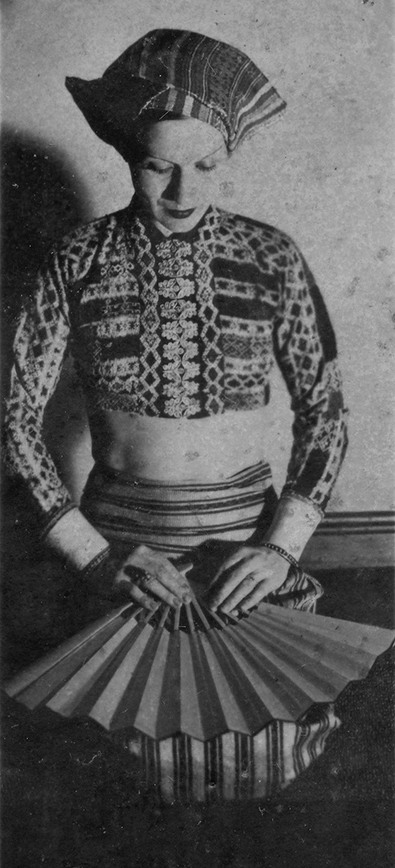

At the age of 20 years, Sofiya refused to assume the traditional feminine gender role in society and traveled to Paris to study at the Louis Paglieri Film School. There, she worked as a fashion and artist’s model and landed small roles in French films.

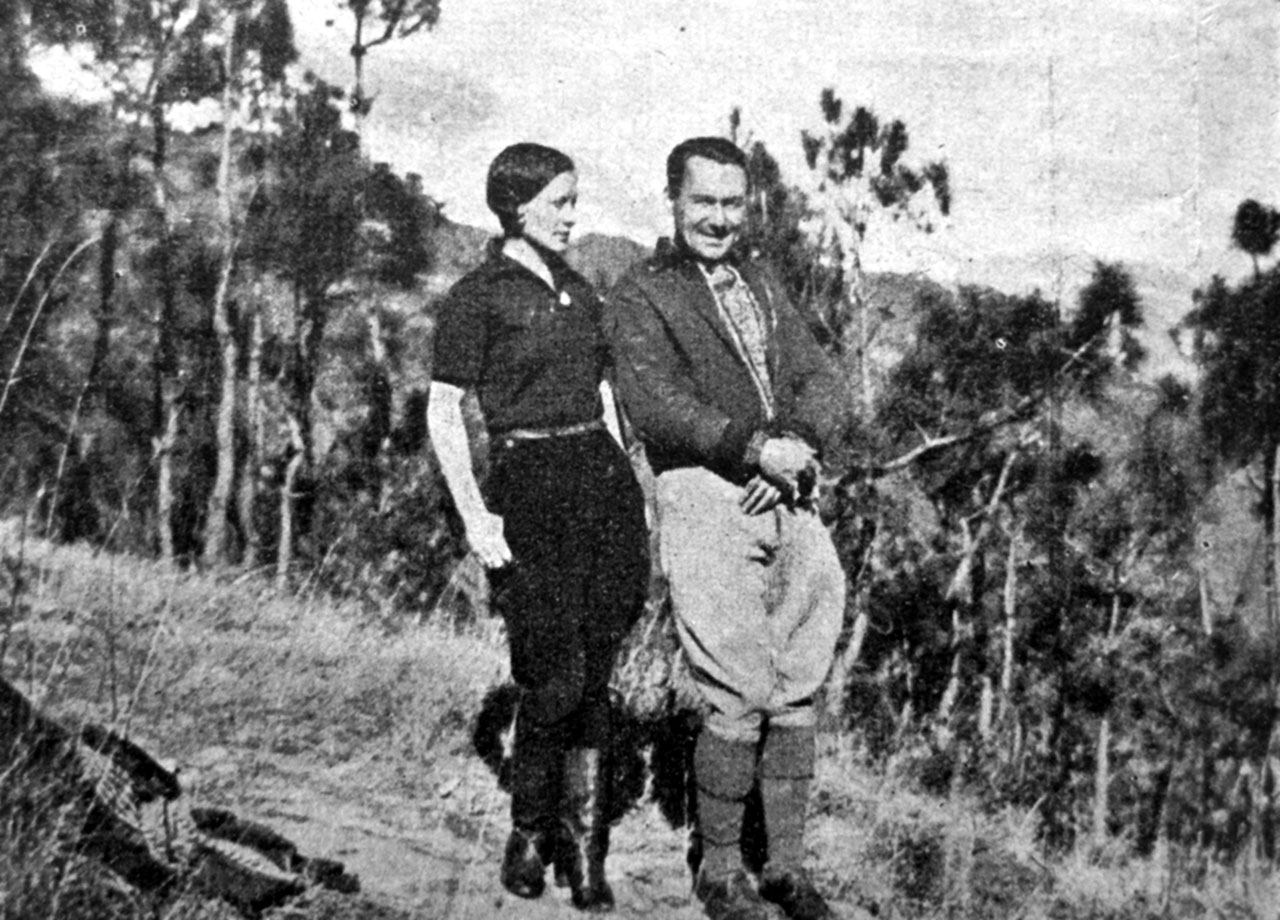

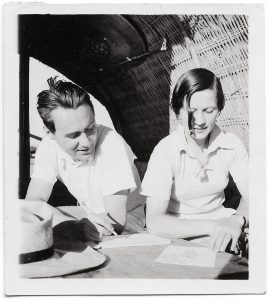

Sofiya fully integrated the Parisian art scene, which was attracting writers, artists, and bohemians from around the world. In this unconventional milieu, she befriended many famous persons, one of whom was Stepan Levynsky, a Ukrainian writer, orientalist, and traveler, who convinced her to drop her budding film career and travel to North Africa. An emancipated and free-spirited young lady, Sofiya even entered into a common-law marriage with French artist and adventurer Christian Caillard, who mesmerized her with tales of his travels to Morocco.

The pull of Wanderlust

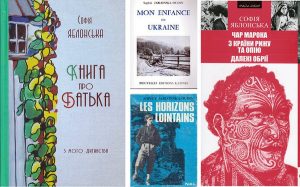

Sofiya Yablonska’s drive and persistence eventually landed her a job with a French film production company. Armed with a movie camera and a notebook, throwing caution to the wind, she packed her bags and made her first three-month trip to Morocco in January-March 1929. It was a revelation for the young woman, who transcribed her impressions in a travelogue published by the Shevchenko Scientific Society, Lviv in 1932 under the title The Charm of Morocco (Чар Марока).

Arriving in Morocco, for the first time in her life Sofiya plunges into a non-European culture and describes rare scenes of everyday life that catch her attention: fire-swallowers, a snake eater, a Senegalese dancer, or a Berber fabulist performing on a central square. She visits Casablanca, Marrakech, Mogador (now Essaouira), Taroudant, Agadir, focusing her camera at every turn and avoiding the frivolous pursuits of humdrum tourism.

“I still don’t like tourists. Why? Because they capture the beauty of Marrakech with their silhouettes, and their cameras breathe black spots on the clear walls of buildings.”

Perched on a building roof looking over the city, she discovers the city through images, sounds, and scents:

“The wind brings the mixed scent of flowers, vegetables, candles, lamb and honey. Drunken with the smells, the sounds of monotonous music and the chirping of birds, covered with the blue sky, I will draw for you the majestic beauty of Marrakech and the life of the Arabs.”

Her impressions are both physical and sensual; she captures the mysterious essence of this strange world and refuses to pass judgment on what she sees. She watches and records a Berber fabulist as he performs on the central square, even though she does not understand his words:

“He drew the attention of the spectators with nothing else but his facial expressions and body movements… It was a perfect, flexible dance. He would break the line of his movements or create an accent with the rise of his voice, facial expression, the meaning of his words. He played with all the muscles of his body, fingers, finger nails; he even used the air he exhaled, and he mixed his play with pauses of total immobility, which led to moments of culmination, taking the spectators’ breath away.”

Wherever she went, Sofiya firmly identified herself as Ukrainian and all her reports were written in the Ukrainian language. Called “the wild Ukrainian” by a French official, Sofiya remained undaunted in her pursuit of the unknown and even used her status as a woman to enter the mysterious world of Arab harems. Describing her visit to this secret place, she relates her conversation with the host:

“I started explaining to him the difference between the Russians and us, drew a map of Ukraine and its neighbouring countries, so that he better understood its location. I told him that there were about forty million Ukrainians and that Ukraine was one and a half times bigger than France. All these explanations I know better than a prayer, because I often have to repeat them to the French and other strangers who know nothing about our existence.”

In the harem, Sofiya also meets a local dignitary (caid), who is ready to give her one of his many wives so that she does not feel lonely during her travels. When Sofiya remarks on the girl’s young age, the caid smiles and tells her that their women are beautiful only when they are young.

– Don’t you think that she’ll long for you and for her home in Africa? inquires Sofiya

– No! Not at all. If you give her a nice dress and some toys, then absolutely not! assures the caid.

– Ask her, please.

– It’s not necessary, madam. Our women don’t know love; they don’t care, and we don’t look for it in their hearts. Why? Because they have no right to choose. Give them freedom of choice and you’ll see that they too will discover love.

Sofiya became an immediate sensation in Halychyna and her travel reports received rave reviews in Galician newspapers and literary journals. Ukrainian writer and literary critic Mykhailo Rudnytsky wrote:

“… The Charm of Morocco: a colourful style, vivid observations, and a cheerful smile on every page. Her style of writing is the most important feature of her work, a manifestation of her talent and skills. Everything else – strange words, grammatical errors, spelling – can be corrected, crossed out, cut from the text before printing. However, how the author looks at a world unknown to us is unique and cannot be inserted by another into the text.”

On more than one occasion during her travels through Morocco, Sofiya throws caution to the wind and ventures into territories that are not controlled by the French administration. She enjoys the excitement of adventurous journeys and avoids luxury hotels, elite cruise ships, local guides, and comfortable vehicles. She shocks both the ‘civilized’ French authorities and the ‘naive’ Berbers when she decides to travel to the Sahara, oblivious of the scorching sun and the dangers posed by wandering nomads and desert creatures.

“The smell of danger has already enlarged the compartments of my heart… The danger looks at me with a hundred of its feverish eyes, attracts me and draws me to itself. Interesting! Can this be the last day of my freedom?”

Asia & China through a camera lens

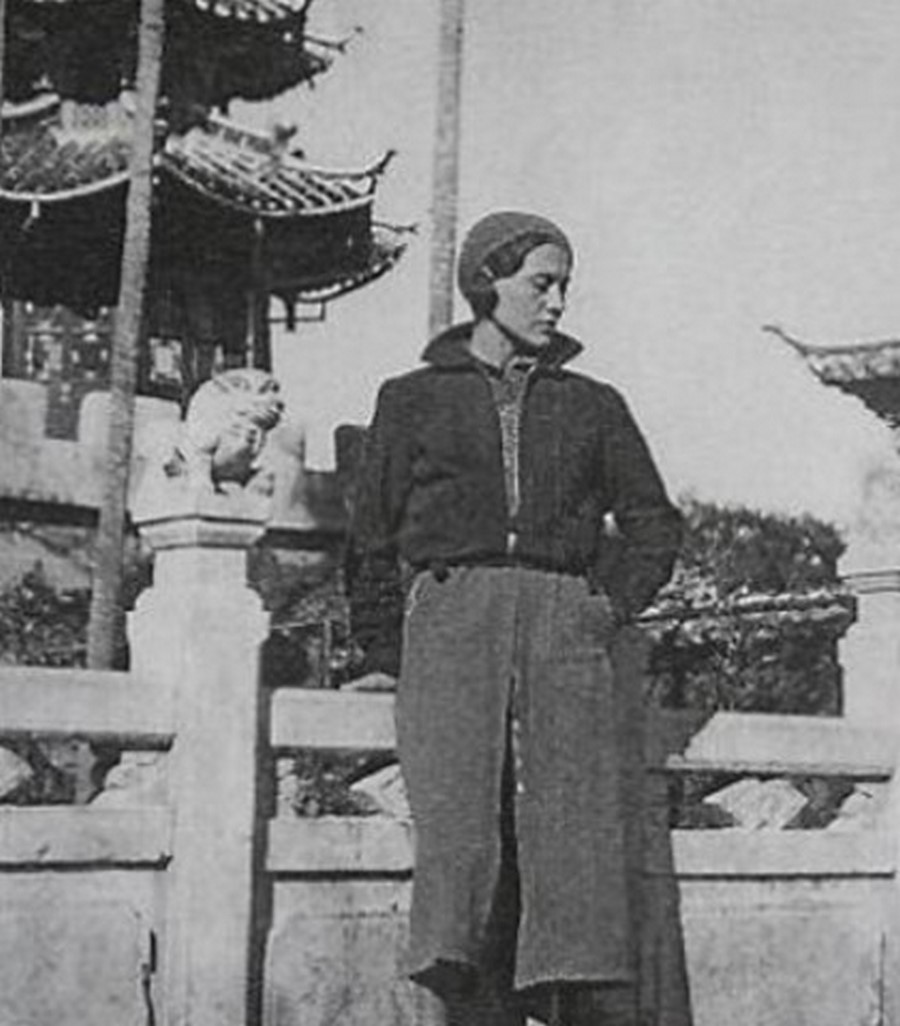

Sofiya Yablonska returned to France, but she had already been bitten by the travel bug and decided to turn her passion into a profession. She found work shooting documentaries with the Société Indochine Films et Cinéma, packed her bags again, and set off for Asia and China.

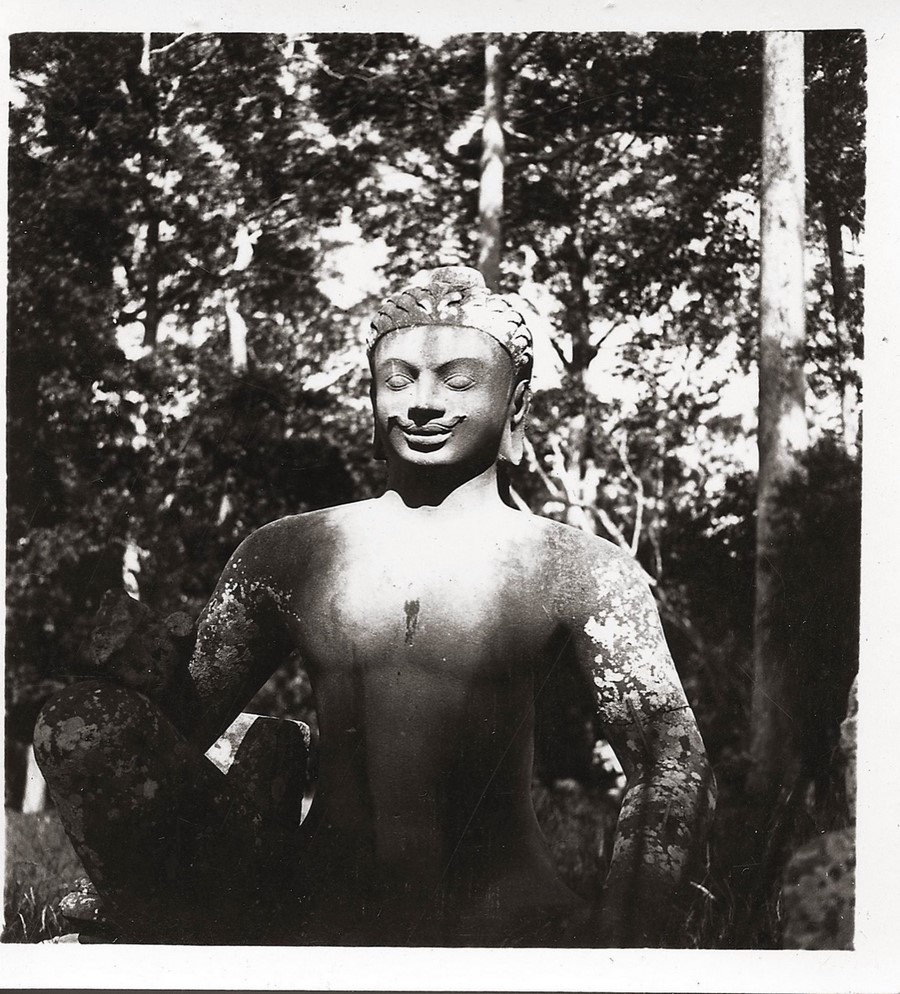

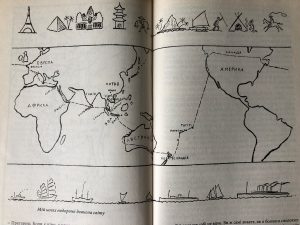

Sofiya does not travel directly to Asia and China, as her curiosity and adventurous spirit drive her to visit remote countries along the way. She stops by Port Said, Djibouti, Colombo, Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), Huế, Hanoi, Laos, Phnom Penh, Angkor, Bangkok, Penang Island, Singapore, Java Island, Bali, Australia (Perth, Sydney), New Zealand (Auckland, Lake Waikaremoana, Wellington) and Rarotonga Island.

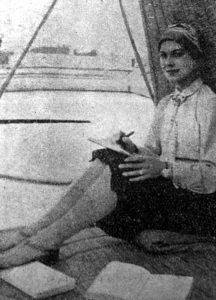

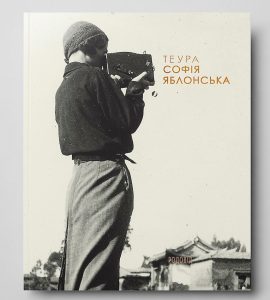

She also fulfills her lifelong dream – an expedition to the exotic island of Bora Bora, set on one of the most beautiful and crystal-clear lagoons in the world, colored in a million shades of blue. She stays there for several months, where the natives give her a new name – Teura, meaning ‘red bird’. During her travels, she meets many interesting individuals, namely French author and traveler Alain Gerbault, who enchants her with his tales of distant lands. Although Sofiya returns to Europe via the United States (San Francisco and New York), she ends her travelogue with her lengthy stay on Bora Bora.

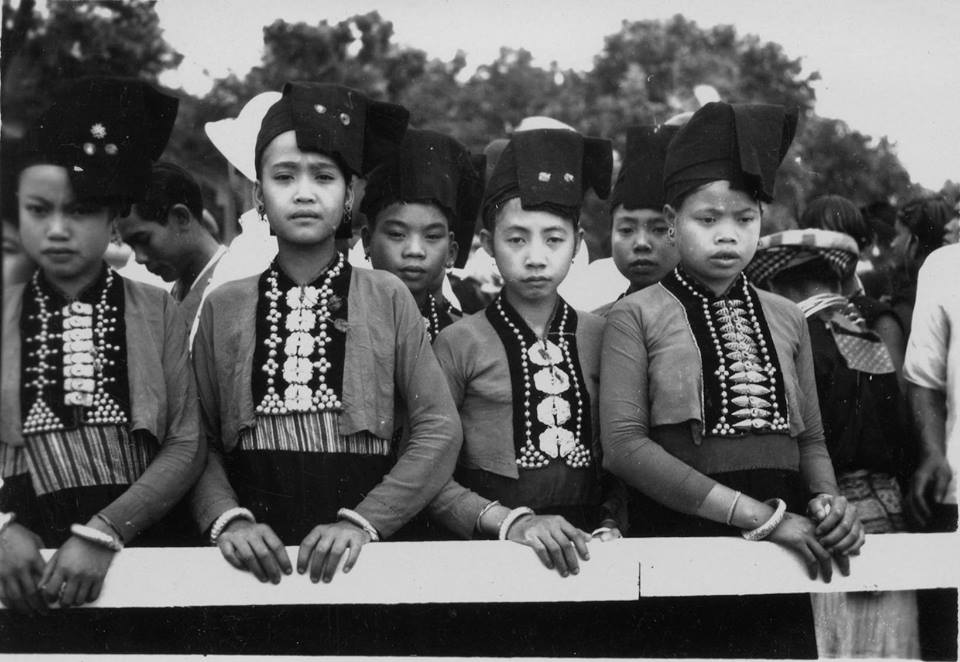

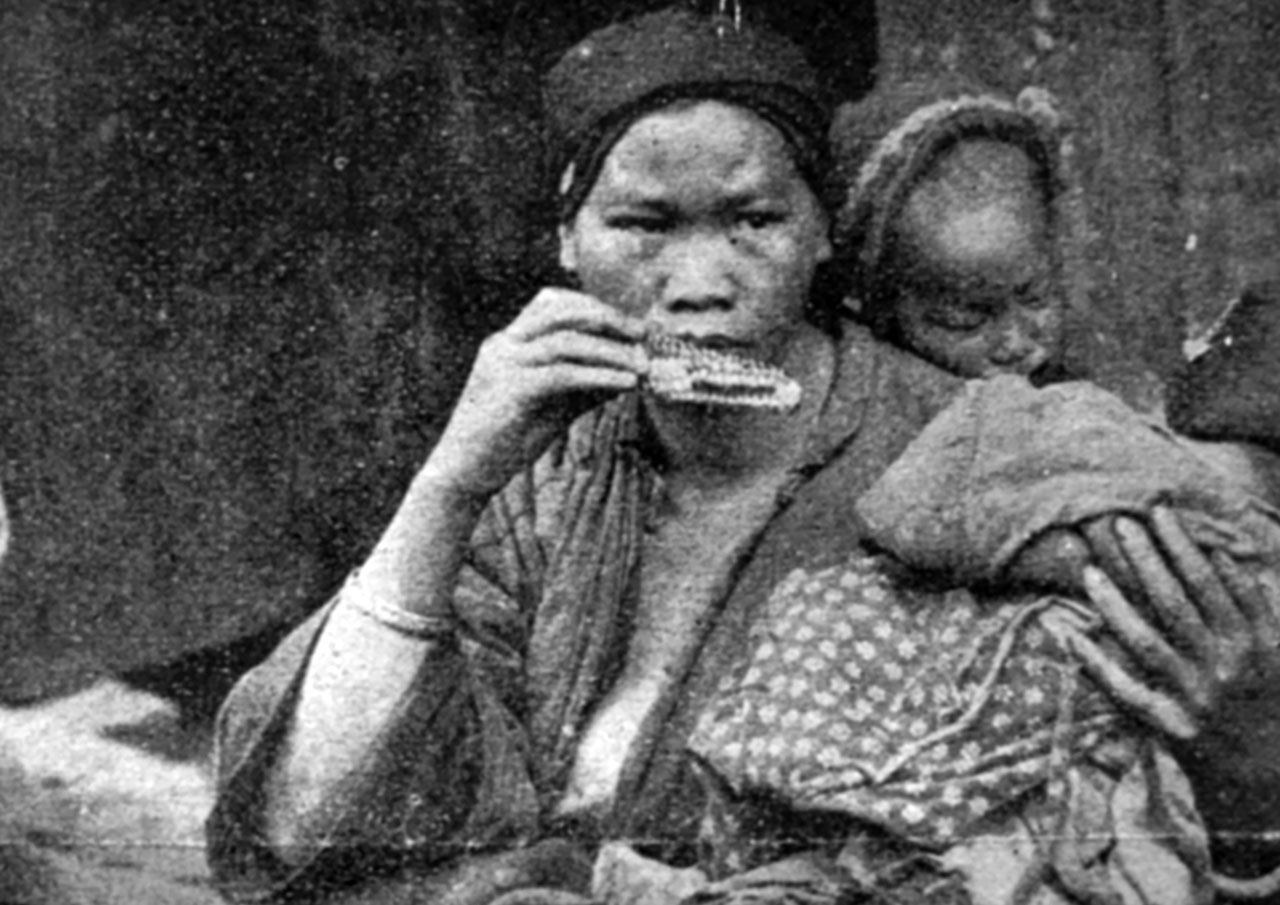

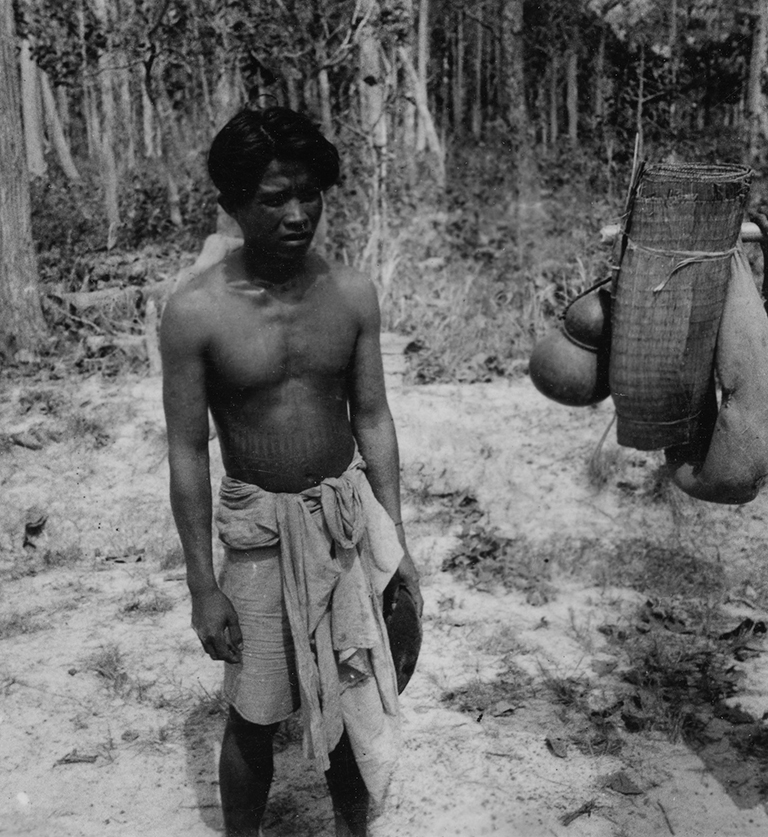

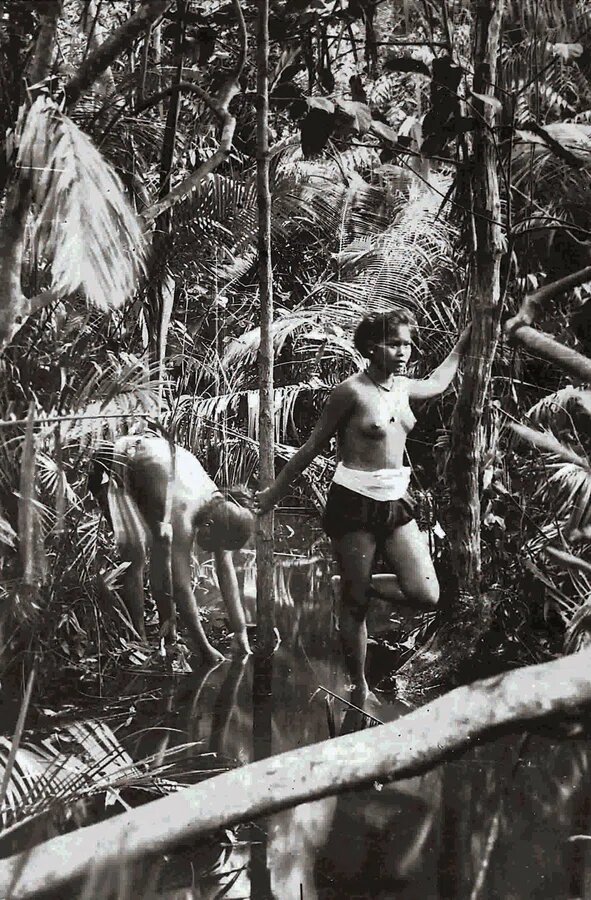

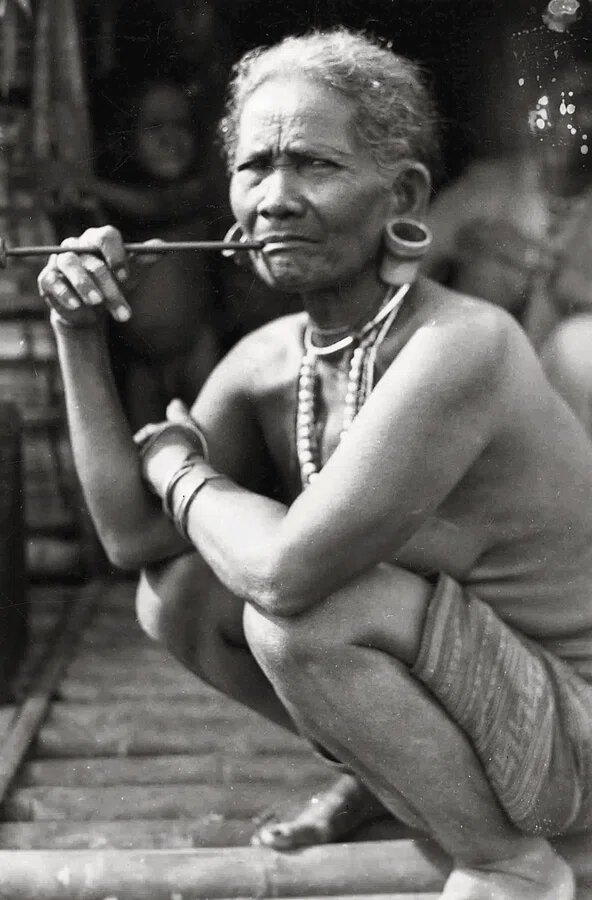

No one in the cinema community believed that Sofiya Yablonska would be able to shoot or record something in these remote lands, because the local population was very wary of ‘white people’ and even more so of a camera, which the locals believed could capture and destroy a person’s soul. But, Sofiya was a determined woman and using her remarkable ingenuity and beautiful smile, she managed to gain the confidence of some indigenous people and deliver images that no one had ever taken before.

Sofiya approached her subjects carefully, using gestures and the power of her smile to capture them on camera. Realizing that she could not take photograph the indigenous population directly, she set up a clever scheme – a fake shop on a busy Chinese street through which she managed to record daily street traffic and passers-by. She showed a keen interest in faces, facial expressions, and articulation:

“The Chinese would stop, approach close [to the shop window], lift their heads up to the light so that I could take pictures up close of their surprised, admiring, smiling or foolish-looking faces. The expression of their squinting eyes was the most interesting for me.”

In time, Sofiya came to realize that she, like most white people, was molded by “European ‘white’ sensitivity, which plays a great role in my observations, because the Chinese, set in their traditions, perceive life and its manifestations in a totally different way.”

In addition, her Chinese experience not only enriched her with new knowledge but also convinced her that the idea of Western Universalism could not be applied in Asian cultures: “Europe is too far away to serve us here with its example or punish us with its laws.”

Confronted by a vastly different world, Sofiya opens up discussions on cultural differences, especially in relation to white European civilization. She avoids romanticizing or idealizing the ‘noble savage’, noting that social inequality exists not only between imperial and colonized cultures but also within each of them.

Sofiya reflects the world through her own sensations and feelings. She does not attempt to distance herself from the events she describes and does not seek to analyze objectively; on the contrary, she attempts to convey her experience immediately and in a subjective manner. Hers is a sensual and instinctive description of the manners, mores, and traditions of the societies and cultures that she encounters, which often question western preconceptions.

“Culture, as I see it, is a totally unstable notion. In the eyes of the Chinese, we are wild, ignorant people, even people without a soul, without thought… The Chinese treat our civilization, our inventions, our progress as empty things without any durability, any sense, despite the fact that they need them sometimes for themselves. “Your inventions haven’t enriched your life, just made it more complicated,” an old Chinese man once told me. And I am afraid that this time he voiced a deep truth.”

Sofiya firmly believed that by experiencing other cultures, we could gain a new understanding of our own culture, revise our ideas and stereotypes about other cultures.

“I believe that human beings can go beyond themselves. Thus, their judgment will become completely different, more uncompromising and more rigorous toward themselves.”

Sofiya regularly sent her travelogues to Halychyna, where her tales were published in women’s journals, namely Zhinocha Dolia and Nova Khata (Woman’s Fate, New Home).

Of course, Sofiya’s reckless travels and independent thinking shocked the Galician establishment and high society, who believed that it was not at all “proper” for a young lady to travel without a chaperone. However, Sofiya’s popularity was such that her travel reports and books were sold out immediately, and the halls and clubs of Lviv were full to overflowing whenever she came to visit and give talks to her admirers and followers.

In 1936, Sofiya published From the Land of Rice and Opium followed by Distant Horizons in 1939, recounting her experiences and adventures in Southeast Asia and China and highlighted by her unforgettable photographs. Both were highly praised by critics and well received by Ukrainian readers thirsting for memorable tales of remote lands.

Family life in Yunnan, China… and L’Île de Noirmoutier, France

During one of her many photo expeditions in China, Sofiya met French ambassador Jean Oudin, whom she married in 1933. They had three children, whom Sofiya raised and educated strictly on her own. It is said that she prepared traditional Ukrainian dishes, such as holubtsi and borshch, for her family and entertained them with stories of her life in Ukraine and Southeast Asia.

One of her sons was Jacques Mirko Oudin, a French politician and senator, who died of COVID-19 on March 21, 2020.

In 1946, the family returned to France, residing first in Paris and then moving to the Island of Noirmoutier on the Atlantic coast after the death of Sofiya’s husband Jean. Sofiya designed several villas on the island, enjoyed sailing the seas in summer and skiing down the Alpine slopes in winter, and returned to writing – a psychological memoir A Book about My Father, where she described her childhood and her Ukrainian family and relatives.

Unfortunately, Sofiya Yablonska did not live long enough to see the publication of her family memoir in 1977. She died tragically in a car accident on February 9, 1971 on her way to Paris to deliver her final manuscript Two Weights, Two Measures, published in 1972.

Sofiya has yet to be popularized, read, and acclaimed in Ukraine, but this is slowly changing. Her works have been published and widely read in France. Poet, journalist and translator Marta Kalytovska (b. October 22, 1916 in Stryi, Halychyna; d. January 16, 1990 in Paris) collected Sofiya’s memoirs and translated many of her books into French: L’année ensorcelée: Nouvelles (1972), Le charme duMaroc (1973), Les horizons lointains (1977), Mon enfance en Ukraine: Souvenirs sur mon père (1981), and Au pays du riz et de l’opium (1986).

Rediscovering Teura, Sofiya Yablonska

The Teura. Sofiya Yablonska project was launched in November, 2018 by the Rodovid Publishing House with support from the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation. Its goal is to re-discover and present the works and life history of Sofiya Yablonska, an outstanding Ukrainian photographer, writer, travel blogger and documentary filmmaker.

Teura refers to a red bird found on Bora Bora. The name was given to Sofiya Yablonska by the island’s indigenous population to show that she was “one of them”. The project features a photo album with a foreword by prominent Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko, Sofiya Yablonska’s biography, and three of her travelogues – The Charm of Morocco, From the Land of Rice and Opium and Distant Horizons (authored by Andriy Benytsky and Veronika Homeniuk, with illustrations by Volodomyr Havrysh). The organizers are also planning an e-archive, which will include Sofiya Yablonska’s letters, manuscripts, and photos, currently stored in collections in Canada, the United States, France, Poland, and Ukraine.

The project was presented in Kyiv, and was attended by the authors, writer Oksana Zabuzhko and Sofiya’s granddaughter from Paris, Nathalie Oudin, who presented priceless manuscripts and memorabilia from her grandmother. The English edition of the photo album was presented at the 39th Salon du Livre in Paris.

As Oksana Zabuzhko writes, the life history of this young woman from Halychyna reads like a melodramatic adventure series. This ‘women with a camera’ simply had no rivals in her field! Working as a ‘white film expert in the colonies’, braving the colonial administration and indigenous peoples, Sofiya had no role models and formed her own experiences, thoughts, and descriptions of the lands that she visited.

“… her travelogues are neither National Geographic nor Lonely Planet, but her own personal reflections on Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand, a kind of non-stop author’s ‘poetic cinema’, where she does not play the ‘lyrical heroine’, but directs her sensory receptors to whatever attracts and affects her personally.” writes Oksana Zabuzhko.

In November 2020, the French Editions Textuel published the much-anticipated World History of Women Photographers (Une histoire mondiale des femmes photographes), a collective survey presenting the works of 300 women photographers, including four prominent Ukrainian women: Sofiya Yablonska-Oudin, Iryna Pap, Paraska Plitka-Horytsvit and Rita Ostrovska.

This publication is part of the Ukraine Explained series, which is aimed at telling the truth about Ukraine’s successes to the world. It is produced with the support of the National Democratic Institute in cooperation with the Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, Internews, StopFake, and Texty.org.ua. Content is produced independently of the NDI and may or may not reflect the position of the Institute. Learn more about the project here.