COVID-19 in Ukraine will grow

var divElement = document.getElementById('viz1599422045616'); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName('object')[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth='424px';vizElement.style.maxWidth='524px';vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height='595px';} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.minWidth='424px';vizElement.style.maxWidth='524px';vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height='595px';} else { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height='595px';} var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

As seen from the graph above, the number of daily new COVID-19 cases in Ukraine has been approaching 3,000 in recent days - which puts Ukraine in the 13th position among countries with the fastest-growing number of COVID-19 cases - and in 18th position by new COVID-19 deaths.

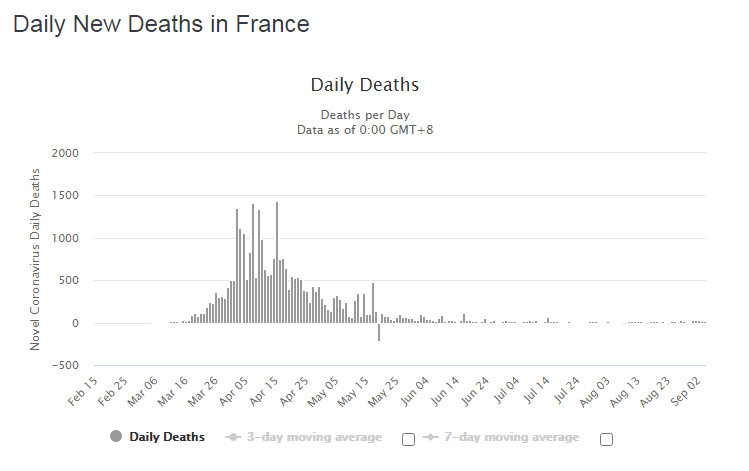

Granted, COVID-19 cases are on the rise not only in Ukraine - many countries in Europe are experiencing a second wave. But the difference between them and Ukraine is that their death rates are not rising:

There are several possible explanations for why death rates are not rising again:

- those most vulnerable to COVID-19 already died in the first wave and now it is the younger populations who were previously on lockdown getting infected;

- there are better precautions for those most vulnerable (such as in retirement homes) and better treatment in hospitals, with improved protocols and increased numbers of oxygenated hospital beds;

- there are more tests being done, meaning that the real "height" of the first "wave" was much higher, but went unregistered.

However, in Ukraine, both cases and deaths are rising and will do so in the future. This is evident from the Effective Reproduction number, or Rt, an estimation of the number of people one infected person will pass the virus on to, on average. Rt exceeds one in nearly all Ukrainian oblasts, meaning that the infection has a stable spread:

One of the reasons that COVID-19 will pick up in Ukraine is the low trust Ukrainians have in the government when it comes to coronavirus. The strict quarantine announced from early March had multiple inconsistencies which irritated Ukrainians and destroyed their trust in official information about coronavirus.

These included severe yet unnecessary restrictions such as bans on walks in parks, which later Ukraine's chief sanitary doctor admitted were made to create a "psychological effect" of stoking fear so that the pandemic would be taken seriously, not to actually prevent the spread of the disease. Or the selective approach to shutting down businesses during the quarantine, when the Epicenter construction giant illegally kept on working while small businesses were closed, some to never reopen.

As a result, most Ukrainians are slacking off regarding coronavirus safety precautions such as wearing masks and physical distancing. A poll found that 42% do not want to be vaccinated against the disease (of them, 33% believe that COVID-19 is a "fake" disease and that its danger is exaggerated). None of this bodes well for the future of the spread of the disease in Ukraine.

Healthcare system already under strain

Let's recall that all COVID-19 safety measures have the goal of preventing a collapse of the medical system by "flattening the curve" of new infections so that the hospitals are not overwhelmed.

A tidal wave of coronavirus patients could not only mean medics will be faced with the unenviable choice of deciding who gets to live; it will also mean non-coronavirus patients don't get urgent treatment. And some hospitals are already overflowing -- and facing a shortage of medical workers at that.

The latter point is worth a separate mention. It can be arguably stated that the Ukrainian healthcare system failed its medics: amid procurement scandals leading to a drastic lack of protective equipment, many medics chose to resign at the onset of the pandemic. Then, roughly 19% of all registered infections were among the healthcare workers -- one of the highest rates in the world. In some places, 19-year-old medical college graduates lacking the necessary experience have taken their place, but the situation remains difficult nonetheless.

Infectious diseases doctor Olha Holubovska believes that Ukraine is only at the threshold of a new wave of infections, which will be precipitated by reopened schools and reports about a lack of hospital beds for coronavirus patients in Kyiv.

In August, the number of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 nearly doubled, and will likely keep growing, since Ukraine still has little effective measures to prevent the spread of the disease: its number of tests per capita is still the lowest in Europe, and processing times are slow, leading to an insufficient localization of outbreaks. Despite creating a UAH 64bn specialized COVID-19 fund, the Ukrainian Cabinet managed to spend most of it on things unrelated to coronavirus, such as the police and road construction, with only UAH 3.1bn reaching the Ministry of Health - meaning that hospitals are not nearly as better prepared for the coming wave as they could have been.

All this is spelling COVID-19 disaster. And some hospitals are already getting a taste of it.

As of now, some hospitals already feel a lack of beds and/or oxygen for patients with COVID-19. Many are being re-profiled to accept the growing number of COVID-19 patients, meaning that those hospitalized with other diagnoses, such as strokes, are being prematurely checked out.

Hospitals in the Odesa Oblast are among the most stressed ones: at places, they are 90% full. Most drastically lack oxygen concentrators.

Kateryna Nozhevnikova, head of the charitable fund "Monster corporation," told LB that many patients incoming from the regions to the COVID-19 reference hospital in Odesa have such low blood oxygen levels that it is impossible to save them, and the hospital itself has only 28 oxygen concentrators, which is already not enough to treat all patients needing oxygen.

Nozhevnikova also tells of situations when patients with severe pneumonia are not admitted to hospitals before they have a positive COVID-19 test - which in itself is problematic because the diagnostic centers are already working at top capacity, meaning there are delays with diagnoses.

In Lviv, hospitals are overfilled, says Nataliya Lypska, head of the charitable fund "Wings of Hope." She says that without severe symptoms of breathlessness, it is impossible to get admitted to a hospital, and recommends having a pulse oximeter handy, so that blood oxygen levels don't drop to dangerously low levels.

However, at least Lviv does not have Odesa's oxygen problems: there is an oxygen factory nearby, meaning that if oxygen concentrators will not be enough, oxygen cylinders with tubes can be used, Lypska says.

Meanwhile, Chernivtsi, the region from where the COVID-19 outbreak started in Ukraine, is running out of hospital beds, and plans to transport coronavirus patients to neighboring regions, told former mayor Oleksiy Kaspruk.