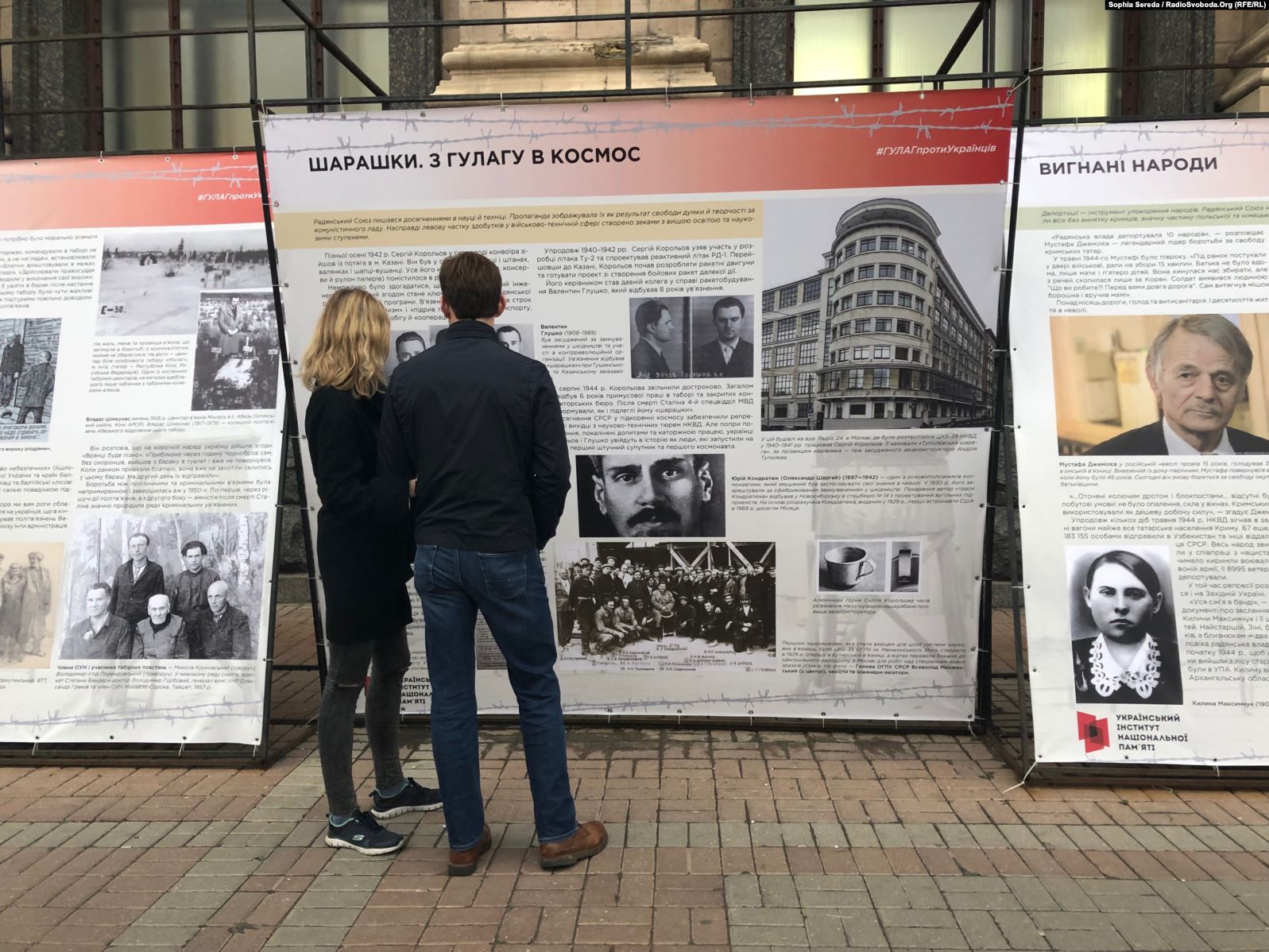

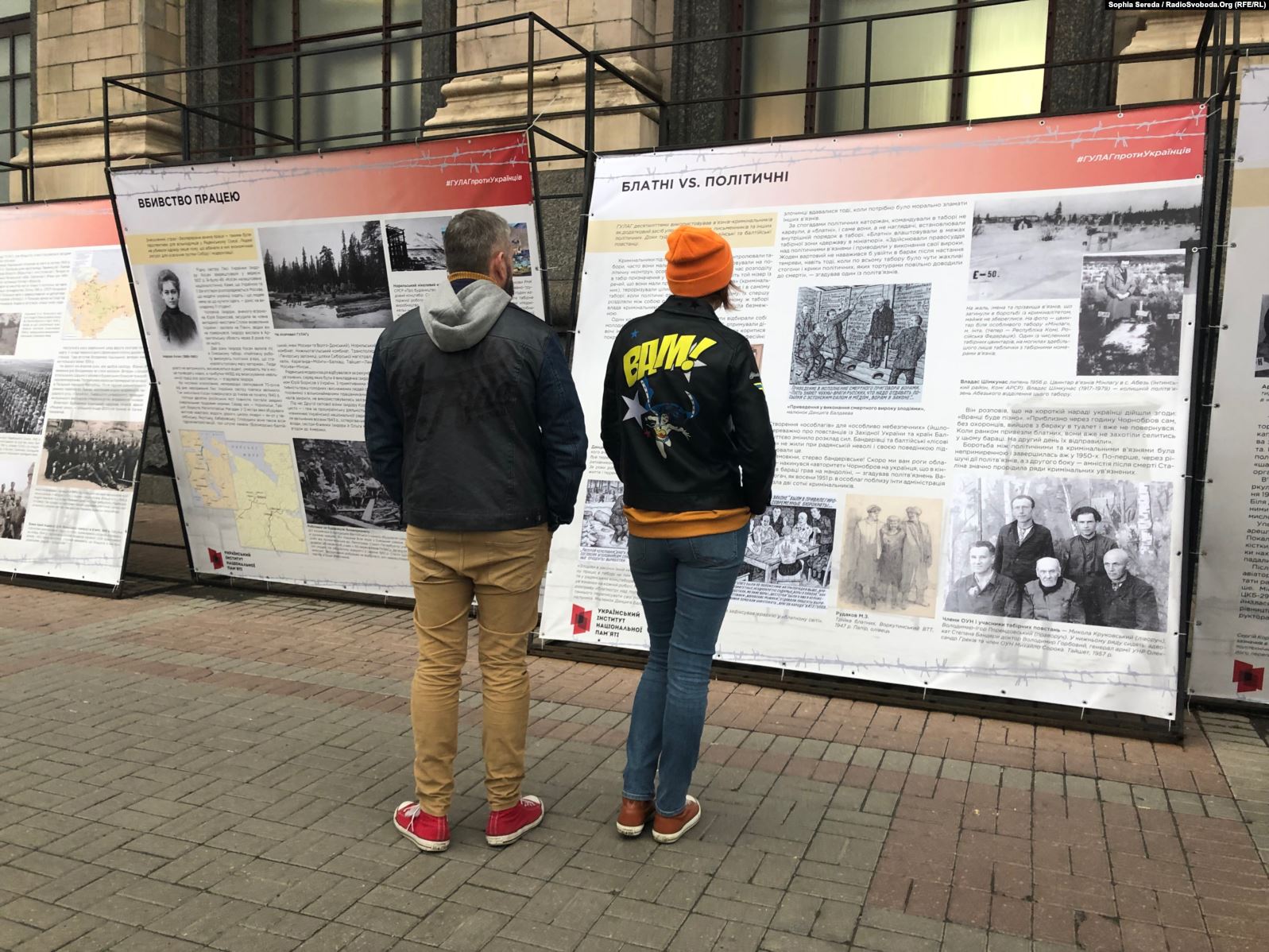

On 8 May, the Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation, an open-air thematic exhibition opened in Kyiv to tell about the triumph of these people and their struggle against the Soviet repressive regime.

"They triumphed, though their struggle stretched for 74 years of existence of the communist totalitarian and its concentration camp system. They triumphed on 24 August 1991, when Viacheslav Chornovil, Levko Lukianenko, and other political prisoners brought the blue and yellow banner into the Verkhovna Rada!" were the words by the chief of academic programs of the Liberation Movement Research Center (CDVR), Volodymyr Birchak, about Ukrainians who had wound up in GULAG but instead of breaking down themselves, they broke up the repressive system of the Soviet Union.

Such people are in the spotlight of the exhibition "Triumph of a human. Ukrainian residents who defeated GULAG" organized by CDVR together with their colleagues from the Ukrainian Institute of the National Memory (UINM), the Lontsky Prison National Memorial Museum of the victims of occupation regimes, and the Branch State Archive of SBU.

"More than 20 million people went through the GULAG system. In 1953, when butcher Stalin died, most of the prisoners were Ukrainian," stresses UINM director Volodymyr Viatrovych.

According to him, the Soviet authorities saw their camp system as a tool of ultimate subduedness, that's why OUN and UPA insurgents made up a significant share of the prisoners.

"Those were the Ukrainian insurgents who brought the 'rebellion virus' into the GULAG premises. The mass riots which occurred in camps in Vorkuta, Norilsk, Kengir broke this system," highlights Volodymyr Viatrovych.

Not only insurgents were forced to go through the Russian camps, but also other various groups of Ukrainians from peasantry to the intelligentsia. They had to cut wood, partake in "communist construction" projects, work in mines within the Arctic circle, end up in secret research facilities known as "sharashkas" or in prison mental hospitals.

One of those who faced this fate was Izydora Kosach, sister of famous Ukrainian poetess Lesia Ukrainka.

For the first time, Ms. Kosach was arrested on denunciation in September 1937. One of her students stated that Izydora was "nationalistically disposed" and that she told that "Moscow administers Ukraine and its wealth," "prominent Ukrainians imprisoned," and "people have no money to buy clothes."

Lesia Ukrainka's sister served her sentence in Onega Camp in Arkhangelsk Oblast, where she cut lumber. Recalling that years, Ms. Kosach mentioned that the hardest duties accrued to political prisoners, who were in the overwhelming majority there.

In early 1940, shortly before the celebrations of the 70th anniversary of Lesia Ukrainka's birth, Izydora Kosach was released after multiple petitions.

But soon, as the World War 2 came to the territory of the USSR, she wound up behind bars again. This time German Nazis arrested her, yet the reason was the same - pro-Ukrainian activities.

When she was free again in fall 1943, Izydora Kosach and her sister Olha fled the USSR to Western Europe and later to the USA.

"I won't come to Ukraine, until slavery reigns there and innocent people are being arrested," stressed Izydora Kosach.

And a Baptist pastor from Kyiv, Heorhii Vins, suffered two times in the USSR for his religious views. At first, he spent three years at a camp in North Ural, and his next term he served in Yakutia.

The camp authorities oversaw that Vins couldn't talk to other prisoners on religious topics, and as such conversations were suspected, Vins was transferred to another place of detention.

In one of the camps, he was "given a red line" as "escape-prone." Thus, Vins was allowed to sleep only near the entrance of barracks, only on his back and not covering his face. Even though, they woke him a few times overnight, raising him questions and blinding him with a flashlight. The day-time was no easier: every two hours he had to visit the guards' office.

However, the strict control wasn't an obstacle for Mr. Vins to sneak in 15 chapters of John's Gospel in a heel of his boots, and a match-box-sized Mark's Gospel sewn to his A-shirt.

It was not enough for the Soviet regime to just banish Vins to GULAG, the authorities of camp abetted criminal prisoners to attempt upon his life promising them premature release.

And while Mr. Vins served his sentence in such conditions, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, Amnesty International, and even the US Congress called upon his release.

It was achieved only in 1979 when Vins and four other prisoners were exchanged for two KGB spies. This is how Mr. Wins was brought to the USA.

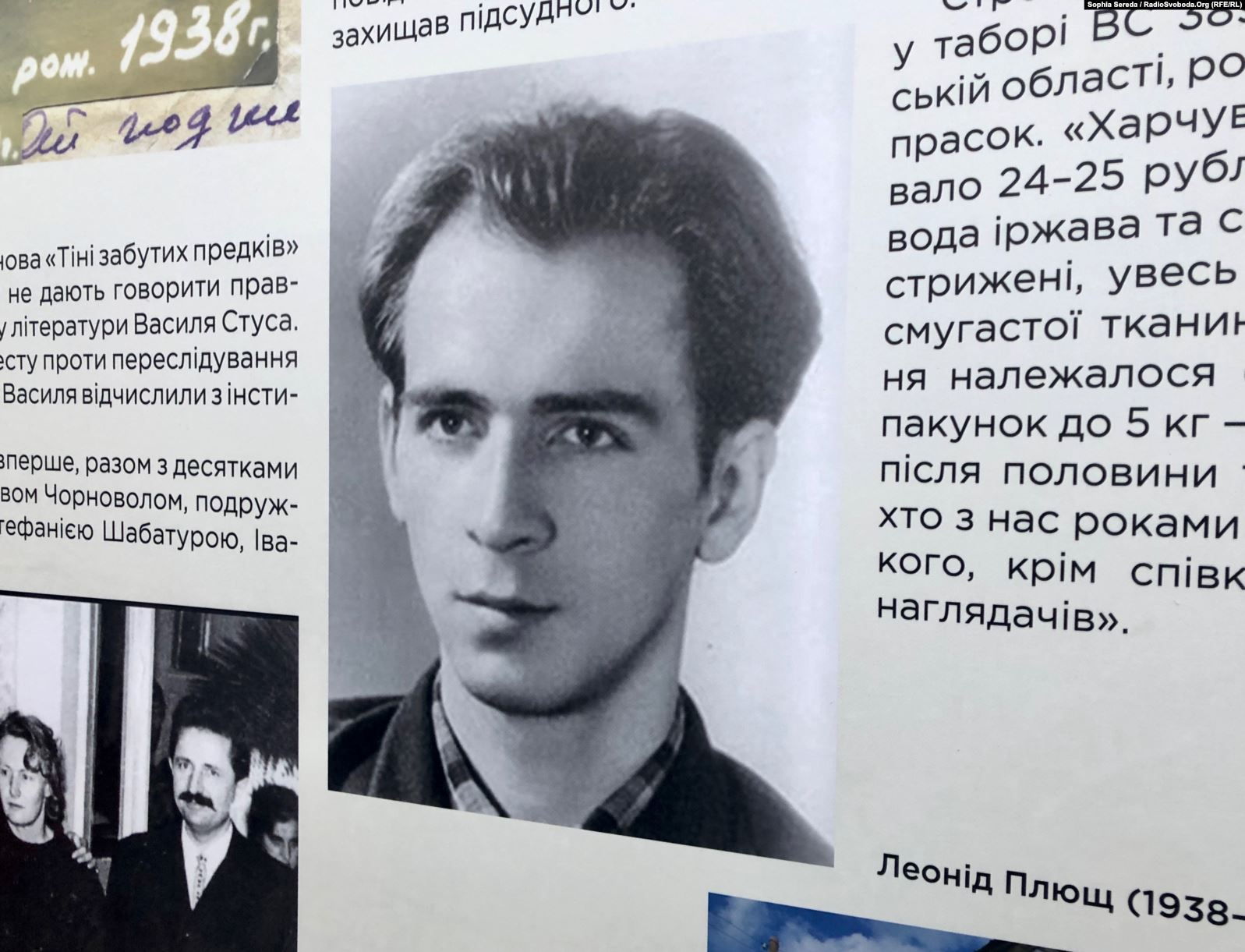

Mathematician and philosopher Leonid Plushch was one more person whom the international community had managed to wrest from the Kremlin's grasp in the second half of the 1970s.

Taking into account "special social threat of his anti-Soviet actions," the Soviet authorities held Plushch in a special mental facility, which was even worse than a camp due to an uncertain term of forced "medical treatment" and the threat for him to reach real madness because of the various "treatment methods" used.

The so-called "sluggishly progressing schizophrenia," with which a special "commission" diagnosed Mr. Plushch, was "corrected" not only by binding him to the hospital bed for many hours, but also with the help of haloperidol, insulin, and triftazine, which caused cramps to his body making him unable to speak even when his wife visited him.

The stories of Leonid Plushch, Heorhii Vins, and Izydora Kosach are several from a few dozens shown by the exhibition "Triumph of a human. Ukrainian residents who defeated GULAG."

"First of all, these stories are about those who managed to withstand mentally, because it wasn't enough for the Soviet Union to break a human physically, the regime also strived to force using its language and respect its values," summarizes Olesia Isaiuk, staff scientist of the CDVR and the Lontsky Prison National Memorial Museum.

The open-air exhibition is available in central Kyiv near the Central Post Office (at #22, Vulytsia Khreschatyk).

Read more:

- From Stus to Sentsov: Ukraine’s Soviet-era political prisoners of the Kremlin

- The Tragic 1972 Vertep in Lviv (photos)

- Soviet-era punishment resurfaces in Crimea: the political abuse of psychiatry

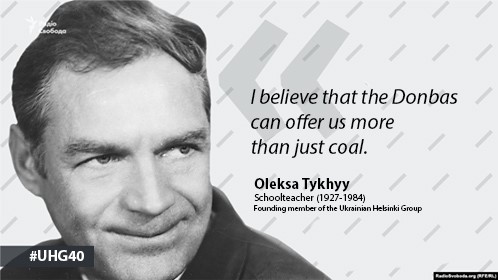

- Ukrainian human rights group that helped bring down Soviet Union turns 40

- Russia’s imperial crackdown on the memory of indigenous victims of deportations

- Ukrainian dissident Krasivsky: Russia is our historical enemy. Only by fighting back we can survive

- Remains of executed victims found in Lviv’s Prison on Lontskoho Museum

- GULAG was not something far away in Siberia: it was all around, even in Moscow

- Moscow secretly destroyed GULAG victims records in 2014

- The Kremlin and the GULAG: Deliberate amnesia

- Ukrainians rose up against the Soviet GULAG at Kengir

- Remembering Soviet atrocities: Solovki and Sandarmokh

- Ukrainians discover stories of repressed relatives in newly opened KGB archives