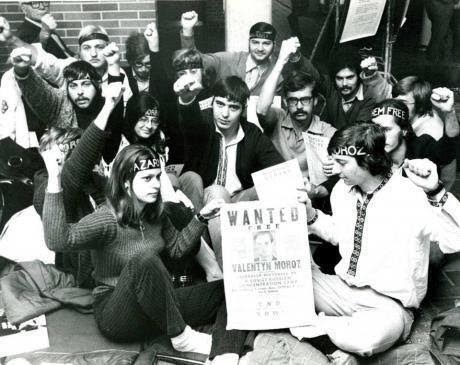

Those who were active in Ukrainian diaspora communities in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s were keenly aware of the plight of dissidents in post-Stalinist Soviet Ukraine. Ukrainians in the diaspora often took measures in defense of these dissidents — demonstrating in front of Soviet embassies and consulates, signing petitions on behalf of persecuted dissidents, getting involved in Amnesty International, or other human rights organizations, and so on.

Once Ukraine became independent, quite naturally, interest in these dissidents faded away. And there was considerable disappointment when it became clear, in the 1990s, that former dissidents would not, or could not, play a major role on the political scene in Ukraine.

There are occasional reminders that the dissident theme is still relevant in Ukraine. For example, the Donbas region, currently a zone of armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, is consistently portrayed by Russia’s ruling politicians as a highly distinctive region — dominated heavily by Russian-speakers — which has little in common with the rest of Ukraine.

Many of Soviet Ukraine’s best-known and most prominent dissidents, however, were born and raised in Donbas.

Among others, these included Ivan Dziuba, Vasyl Stus, Ivan Svitlychny, and Nadia Svitlychna. They were deeply attached to their regional homeland (mala batkivshchyna), and their biographies underline how Donbas was and continues to be, an integral part of Ukraine. One of Dziuba’s most recent publications, for example, is a series of essays entitled Donetska Rana Ukrainy (Ukraine’s Donetsk Wound), 2015.

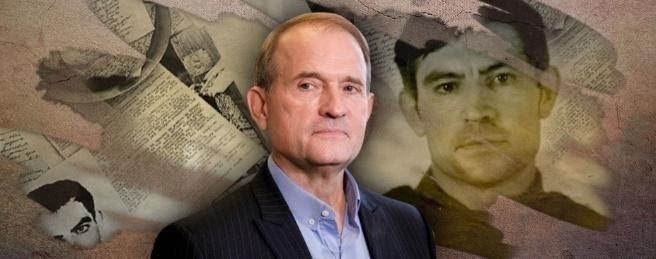

Today in Ukraine, one of the most unpleasant, even odious, politicians on the political stage, Viktor Medvedchuk, had a curious and unfortunate dissident connection — both for him and especially his client. Medvedchuk was the state-appointed defense attorney for the prominent poet and dissident Vasyl Stus, during the 1980 trial that led to the imprisonment of Stus and his tragic death five years later.

During this trial, Medvedchuk made no meaningful effort to use the powers he had (although they were limited) to defend his client. Moreover, in his closing speech at the trial, Medvedchuk went so far as to state that Stus’s “crimes” deserved punishment.

In 2019, Medvedchuk took the prominent Ukrainian journalist Vakhtang Kipiani to court for publishing a book entitled The Case of Vasyl Stus that provides detailed information about Medvedchuk’s very dubious role as a defence attorney.

During the last few years, the issue of persecution for one’s political convictions has re-emerged as a sadly relevant theme for Ukraine. Since the Maidan Revolution of Dignity in 2014, a considerable number of Ukraine’s citizens have been harassed and imprisoned — in Russia as well as Russia-occupied Crimea — because of their political views and activities.

These individuals, like their Soviet dissident predecessors, are prisoners of conscience, in the full sense of the term.

Also worth noting, several former dissidents are still quite active. A few examples are: Myroslav Marynovych, vice-rector of the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, social activist, co-founder of Amnesty International Ukraine, and a founding member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group; Mustafa Dzhemilev (Abdülcemil Kırımoğlu), a highly respected figure in the Crimean Tatar community, and a constant presence on Ukraine’s political scene; and psychiatrist Semen Gluzman, an active critic of Ukraine’s healthcare system and, in particular, the atrocious conditions in Ukraine’s psychiatric institutions.

- Read our interview with Myroslav Marynovych: Soviet political prisoner: international pressure can release Ukrainian prisoners of the Kremlin, but there’s not enough of it

Most former dissidents, however, have passed away. Among the well-known dissidents who died recently were Valentyn Moroz (d. 16 April 2019) and Levko Lukianenko (d. 7 July 2018).

Who is a dissident?

How do we define who was, or was not, a dissident in the Soviet Union? A Soviet dissident, quite simply, was an individual who not only strongly disagreed with certain aspects of official Soviet norms — political, religious, socio-economic, or other — but who also, at some point, came into conflict with the Soviet authorities because of this disagreement.

In effect, it was the Soviet authorities who defined who was a dissident. An obvious conclusion, given the Soviet Union’s large and powerful repressive apparatus, and its constant and pervasive monitoring of citizens.

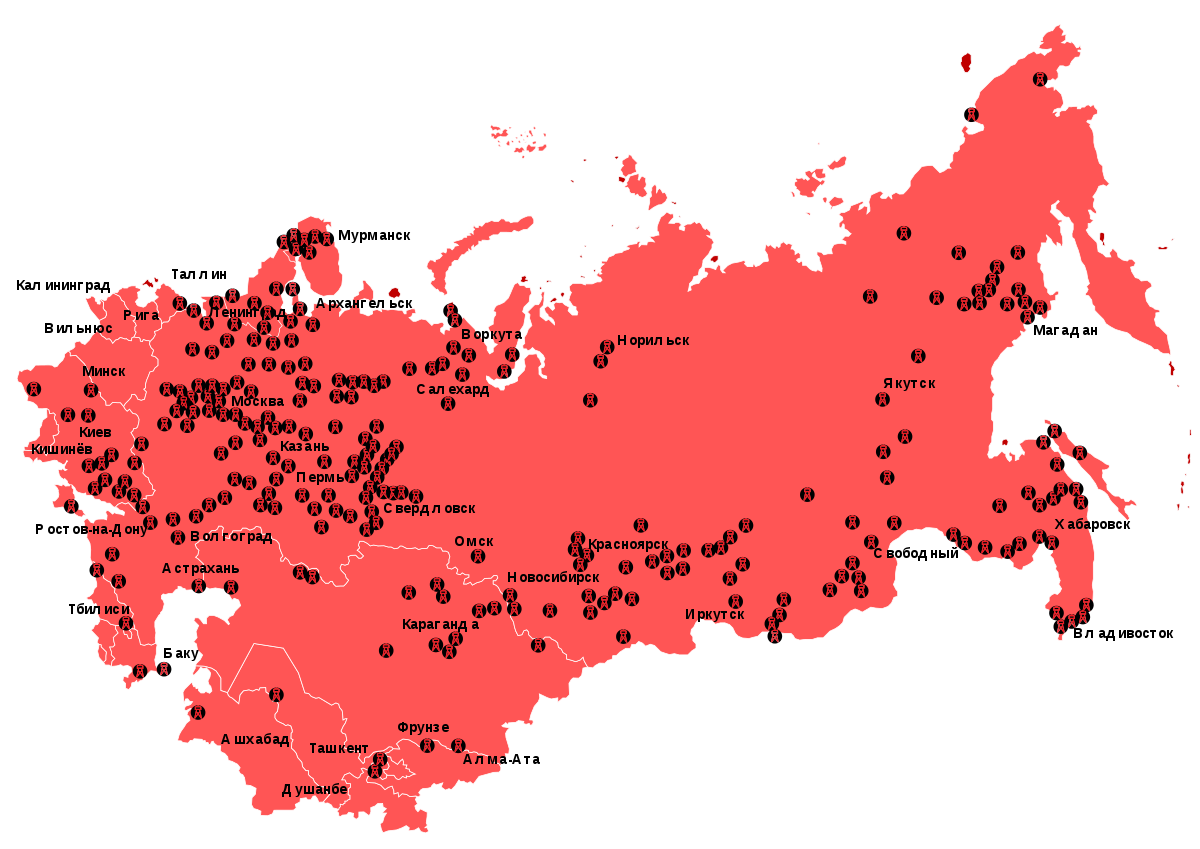

This figure does not include, however, many or most religious prisoners of conscience, often falsely accused of ordinary criminal acts (so as not to draw attention to their real activities). Also excluded are those detained in psychiatric institutions because of their “anti-Soviet” activities, and others.

More than 6,000 prisoners of conscience in the Soviet Union over a period of 30 years may appear to be a relatively small number. After Stalin’s death, however, Soviet repressive policies became quite selective, and the Soviet authorities no longer engaged in often arbitrary acts of mass repression, as in earlier decades. The new policies focused on intimidating and deterring, instead of imprisoning, individuals who engaged in independent political and socio-cultural activities that the authorities considered to be “anti-Soviet” in nature.

These could include any one or more of the following:

- reading and circulating samvydav (samizdat, self-published) materials;

- conducting anti-Soviet conversations at the workplace;

- becoming active in a “non-approved” religious group;

- meeting with foreigners in an unauthorized context; and the like.

At some point, the vigilant state apparatus usually became aware of such activities. “Offending” individuals were then strongly discouraged from continuing such pursuits and subjected to so-called “prophylactic measures.” A strange term, “prophylactic” literally means “intended to prevent disease,” and those who underwent such “prophylaxis,” even if they were not arrested or imprisoned, can also be considered dissidents.

Typically, prophylactic measures consisted of one or more “informal chats” with a “friendly” KGB officer who expressed “concern” that an individual was “deviating from the behavior” characteristic of a good Soviet citizen. Those summoned for such chats were usually asked to cooperate with the authorities by informing on others. Most refused or cooperated at a minimal level, but thinly-veiled threats (e.g., that they or family members could lose their jobs, be denied higher education, and so on) were usually used to encourage, at a minimum, their passivity. These measures were generally quite successful.

According to one estimate, during the late fifties through to the mid-eighties, more than half-a-million Soviet citizens were subjected to this brand of intimidation. A very considerable number were from Ukraine.

All dissidents were not the same

It should also be noted that the dissidents had very disparate backgrounds, and they were not part of a single coherent community.

Although they sometimes interacted, several different dissident movements were active in Ukraine. With the advantage of hindsight, they can be roughly categorized in these terms: national democrats and nationalists; members of religious organizations, not officially approved, and thus harassed by the state; Jewish activists (“Refuseniks”), demanding the right to emigrate; those committed to a broad, general human rights platform; those agitating for greater workers’ rights; and others.

Notably, almost all Crimean Tatars resided outside of Ukraine — due to their brutal deportation in 1944 and continuing to the late 1980s. They should also be included in a broadly defined grouping of dissidents linked to Ukraine. Their protest activities were political in nature and directly linked to their demand to return to Crimea in Ukraine.

How active these various dissident communities were, and how much support they had, also varied a great deal. By focusing on those who were sentenced, or subjected to “prophylactic” measures, because of their political activities — as well as examining the samvydav materials they prepared and the extent of their circulation — it becomes clear which was the largest and most dynamic dissident movement in Ukraine. The best-known grouping, with the most actual or potential support, were the national democrats and nationalists.

Not a club, no underground

Ukraine’s dissidents were not members of a coherent organization or part of an underground society. Rather, in the centers where they were most active (Kyiv and Lviv) they consisted of a loosely knit set of individuals who devoted much of their time to preparing and surreptitiously circulating samvydav.

The most active dissidents functioned as “hubs” for the collection and dissemination of petitions, pamphlets, and other samvydav publications. They focused on government repression (including the harassment and imprisonment of dissidents), Russification and other forms of cultural discrimination, and more. Most of these publications were then smuggled out of Ukraine and made their way to the West, fueling protests in the diaspora.

The most widely known dissidents — “mainstream dissidents,” as it were, included Viacheslav Chornovil, Ivan Svitlychnyi, Nadia Svitlychna, Mykhailo Horyn, and Ievhen Sverstiuk, to name a few. Other, lesser-known dissidents, within major centers of Ukraine, included Nina Strokata-Karavanska (Odesa), Iosyf Zisels (Chernivtsi), Henrikh Altunian (Kharkiv), and Ivan Sokulsky (Dnipropetrovsk, now Dnipro), and others.

Example of samvydav (left) and various collected works, displayed in Kyiv museum dedicated to dissidents. Source: smoloskyp.com.ua

There is no objective way of assessing the importance and legacy of the dissidents of Soviet Ukraine. However, the best-known dissidents from Ukraine became true symbols of courage. They stood in defiance of authoritarian rule, opposed Russification, called for freedom of speech, and demanded the same democratic rights taken for granted in the West.

But they were more than symbols. Instead of dwelling on their symbolic role, it is more significant to understand and assess their lasting contributions to Ukraine and its development.

Dissidents and History

The role of Ukraine’s dissidents in the historical process, and as an important link to Ukraine’s past, is key. Several historians — part of the broader dissident community themselves — addressed issues in the nation’s history in ways that the Soviet authorities considered to be controversial and undesirable. Among these historians were Mykhailo Braichevskyi, Olena Kompan, and Olena Apanovych.

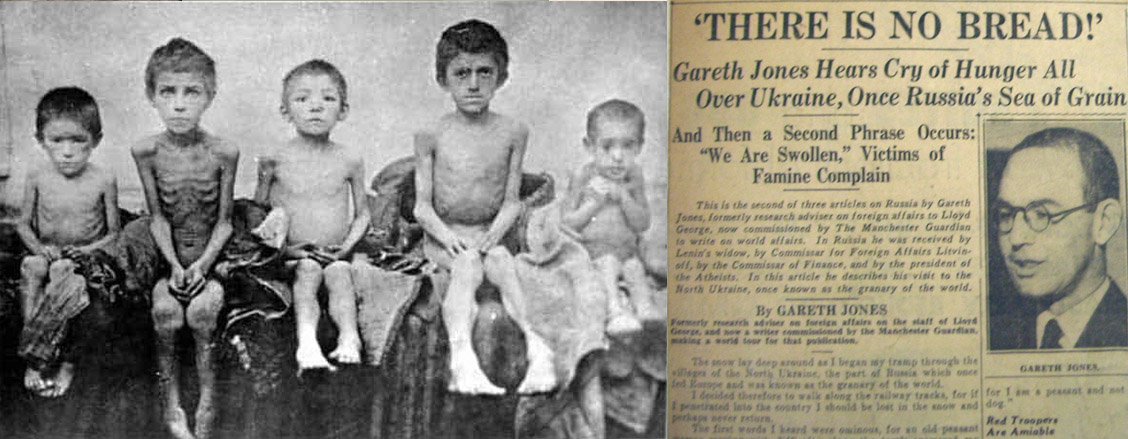

There have been numerous traumas and discontinuities in Ukraine’s recent history. In particular, the first half of Ukraine’s troubled 20th century included WWI and post-war conflicts on the territory of Ukraine, purges of Ukraine’s elites and the famine now known as Holodomor in the 1930s, as well as the bloody and traumatic events of WWII, followed by post-war resistance to the imposition of Soviet rule in Western Ukraine.

These events had a terrible impact on the overall population of Ukraine — the Holodomor alone killing at least four million — and decimated Ukraine’s elites, especially its intellectuals. Some who survived repressive Soviet policies fled the Soviet Union. The majority who remained usually became passive and tended to conform — at least on the surface — to prevailing Soviet norms. As a result of their silence, the children and grandchildren of these survivors usually knew little or nothing about what their elders had experienced.

This problem, of suppressed historical memories, was less marked in Western Ukraine, where memories of postwar resistance to Soviet rule were still strong in the 1950s and 1960s. But it posed very great challenges in the rest of Ukraine. Here, many students and young intellectuals wanted to take advantage of modest changes for the better, during the brief-lived “thaw” that followed the death of Stalin. They were often remarkably ignorant of Ukraine’s history. Many, however, especially among those who became dissidents, were also very determined to correct this situation.

Several individuals who were active participants in the dynamic socio-political and cultural life of Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s, survived long periods of imprisonment. Some of them were not afraid to speak out and soon found themselves surrounded by young activists eager to learn all they could about their experiences. The best-known of these survivors was the writer Borys Antonenko-Davydovych who, after many years of imprisonment (1935-1947, 1951-1956), played an active role in the dissident community in Kyiv, in the 1960s and 1970s.

Another influential survivor was Nadia Surovtsova. She was an active participant in the turbulent revolutionary events in Ukraine after 1917, and then lived and worked abroad for several years. After returning to Soviet Ukraine in 1925, she was detained and spent almost 30 years in the Gulag, from 1927 to 1954. Upon her release, Surovtsova lived for another 31 years in Uman, and almost all the “Shistdesiatnyky” (Sixtiers), the cultural nonconformists of the 1960s, flocked to visit what became known as the “Salon Surovtsovoyi.”

Individuals such as Antonenko-Davydovych and Surovtsova inspired many who later became active dissidents. They provided them with crucial links to Ukraine’s recent past, especially the cultural renaissance of Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s.

The dissident Les Taniuk, the founder of the Kliub Tvorchoi Molodi (Club of Creative Youth) (KTM), which played a central role in bringing together those active on Kyiv’s cultural scene in the early 1960s, was particularly fascinated by Ukraine’s past. Taniuk consistently and persistently tracked down and gathered information from or about those active in the cultural and socio-political life of Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s. He also compiled detailed lists of those, from Ukraine, who had been repressed in the 1930s.

Taniuk’s activities were reflected in his almost fanatical devotion to personal diaries that he began to compile in 1956.

Publication of these diaries (which include letters, documents, photos, sketches, and more) began in 2003. They continued to be published after Taniuk’s death in 2016. To date, 43 volumes (average of 600-800 pages) have been published, with a number of volumes yet to appear. They are an invaluable source of information about cultural and socio-political life in Ukraine from the late 1950s onwards.

The diaries also contain detailed and valuable information about Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s. A person of almost universal interests, Taniuk has been described as “the guardian of Ukraine’s historical memory.”

In doing so, they helped to overcome the traditional divide between Western and Central/Eastern Ukraine. Initially, this was a result of informal contacts between Kyiv and Lviv in the early 1960s. For example, many activists from Kyiv often spent part of their summers hiking in the Carpathians, together with friends and colleagues from Lviv.

Later, the regional bonds strengthened, as a result of joint imprisonment in “corrective-labor” camps. Former political prisoners have often nostalgically referred to the animated discussions in these camps, noting that for many dissidents they played an important role as informal “universities.”

Some of the information compiled by dissidents is now available in the various archives which have been opened in Ukraine in recent years. But nothing can serve as a substitute for the meticulous work — carried out by Taniuk and other dissidents in the 1960s — in tracking down survivors of repression in the 1930s, and documenting their experiences. Equally important was the crucial period just before, and after, Ukraine’s Independence. Many dissidents finally had an opportunity to speak out and gain a broader public audience. They also became unique sources of reliable information about Ukraine’s recent history at a time when little such information was readily available.

Dissidents as historical actors

Apart from their efforts to throw light on the past, some mainstream dissidents also had a significant impact on how Ukraine’s recent history was interpreted outside of Ukraine. For example, throughout the 20th century, the views of most Western scholars and politicians regarding the Soviet Union were characterized by a strong Russo-centric bias. Many elements of this bias lasted until the collapse of the Soviet Union and later.

Nonetheless, dissident documents from Ukraine poked massive holes in Soviet propaganda efforts that sought to portray the Soviet Union as a “friendly family of nations.” Standing out as especially important works in the 1960s were Ivan Dziuba’s Internationalization or Russification and Viacheslav Chornovil’s Chornovil Papers, both published in a number of languages, including English.

Reading such documents, and following developments portrayed in the Chronicle of Current Events (the most important Soviet human rights journal), it was clear that a disproportionately large number of Soviet political prisoners during the post-Stalin period were from Ukraine and the Baltic region (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania).

Those who followed the human rights situation in the Soviet Union, and did not rely primarily on official Soviet sources, thus developed a better understanding of the tumultuous developments of the late 1980s and the ensuing collapse of the Soviet Union.

Dissidents in independent Ukraine

Some detractors have emphasized that the former dissidents did not play a prominent political role in post-Independence Ukraine. One should note, however, that Viacheslav Chornovil finished in second place during the presidential elections in 1991, garnering close to 25% of votes. Meanwhile, Levko Lukianenko finished in third place, taking almost 5% of votes.

Perhaps modest results, but the electoral campaigns of these former dissidents were launched and conducted in difficult circumstances. Political and media reforms were late and hesitant in Ukraine, lagging far behind developments in Russia. In the late 1980s, former dissidents in Ukraine had almost no access to the official and dominant state-controlled media.

Not to mention that over several decades — including the pre-electoral period — state-controlled media had consistently and aggressively portrayed Ukraine’s dissidents as nationalist extremists or, at best, eccentric misfits. In these circumstances, the 1991 electoral results were reasonable.

In the years that followed, the former dissidents were largely hampered by limited access to financial resources and internecine squabbling and failed to have a significant impact on Ukraine’s political scene.

Still, in the early 1990s there was a vocal faction of former dissidents in Ukraine’s Parliament who, during this critical period, did their best to counter the influence of old-guard communists. They also had a positive influence on Ukraine’s first president, Leonid Kravchuk. Paradoxically, he had earlier been a leading figure in Communist Party propaganda activities directed against nationalist and religious “deviations” in Ukraine.

However, as Ukraine’s president, at times Kravchuk worked closely with the former dissidents he had earlier targeted, often taking their agenda into consideration.

Belarus provides an interesting contrast. In a recent comment, former dissident Semen Gluzman noted:

“US ambassador to Ukraine William Green Miller once asked me: “You, Ukrainians—you are very close to Belarusians. Why did a dictator come to power in Belarus, while you have democracy?”

I explained the only way I could: “You see, I am not an expert on ethnic psychology. I can only offer the perspective of an ordinary man. In Brezhnev’s time I was in Soviet political camps, where Ukrainians constituted about a third of political convicts. For many years, up to the time of Gorbachev, I did not see in the camps a single Belarusian, a Kyrgyz, a Kazakh, a Tajik….”

The lack of a tradition of political and human rights dissent in Soviet Belarus is very likely one of the reasons why the authoritarian rule of Alyaksandr Lukashenka so readily took root in independent Belarus, and persists to this day.

Dissidents and inter-ethnic relations

The role of mainstream dissidents in encouraging positive, tolerant, inter-ethnic relations in Ukraine should be acknowledged. Several prominent mainstream Ukrainian dissidents, for example, had a strong and enduring interest in the troubled history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

Among these dissidents was Ivan Dziuba, who on many occasions — including in 1966 in an important speech at Babyn Yar — consistently spoke out against, not only anti-Semitism, but all forms of intolerance and xenophobia. Other prominent dissidents with a strong and genuine interest in Ukrainian-Jewish relations included Yevhen Sverstiuk and Leonid Plyushch.

Many other Ukrainian dissidents had little knowledge of or interest in this topic, and some were not free of the anti-Jewish stereotypes widespread in Ukraine. However, the camps where many of them were imprisoned played an important educational role.

Quite a few prisoners of conscience in these camps were of Jewish background, and the camp administration tried to take advantage of this, in what they considered to be a “creative” fashion. The camp’s KGB officer would call in, one at a time, Jewish prisoners and start conversations along the following lines:

Why on earth are you engaging in hunger strikes, and signing joint petitions, together with Ukrainians? Why you know that Ukrainians are your historical enemies – they’re pogromists who over the centuries have slaughtered countless numbers of Jews.

Then the same KGB officer would have analogous conversations with Ukrainian prisoners:

Why are you cooperating with and protesting together with Jews? After all, you must know that Jews are bloodsuckers who have exploited Ukrainians throughout history.

The KGB must have been losing its touch, because this manipulation was so blatant that many of these prisoners compared notes and quickly figured out what was going on. In several cases, the joint imprisonment of Jews and Ukrainians led to friendships that lasted long after the prisoners were released.

Various aspects of Ukrainian-Jewish relations still provoke heated debates in Ukraine, and in the Ukrainian diaspora. But the tradition of cooperation in the camps where many political prisoners were detained had a significant long-term impact on these relations.

Rukh

In the late 1980s, former political prisoners — some newly released from imprisonment — became increasingly active on the political scene in Ukraine, and they played a central role in the creation of the umbrella opposition organization Rukh (Movement). They were keenly aware, partly as a result of their experiences when imprisoned, that the still very powerful Communist Party would actively play the “ethnic card.” The party used it as a powerful instrument of divide-and-rule against Rukh, by portraying its leadership as intolerant, xenophobic nationalists.

By no means, all dissidents in the national-democratic or nationalist camps were enthusiastic advocates of minority rights. Some former dissidents, especially in Western Ukraine, adhered to an approach that was a version of “Ukraine for Ukrainians” (meaning ethnic Ukrainians) that was implicitly intolerant, with racist overtones. In fact, it was not unusual that in public, dissidents would express politically correct rhetoric about the need for good inter-ethnic relations in Ukraine, but in private would express very different and less positive views.

And even before Rukh fell into obscurity — partly as a result of bickering among its leading figures — its Council of Nationalities was disbanded in 1993. One of the reasons was the atmosphere of growing disagreements, within Rukh, about the role of minorities in the new Ukrainian state.

Mainstream dissidents, such as Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, and Leonid Plyushch, remained throughout the post-Independence period, consistent opponents of all forms of intolerance and xenophobia in Ukraine.

The dissidents and Crimean Tatars

The “dissident factor” also helps to explain the consistent loyalty to Ukraine of the Crimean Tatars. When they began to return to Ukraine in large numbers in the late 1980s, Soviet Ukraine’s authorities did little to help or support them — on the contrary. And even in the nineties, there was little government assistance for the Crimean Tatars, who generally lived in very difficult conditions.

The Crimean Tatars, therefore, had no good reason to be particularly loyal to Ukraine. This was in a context where on several occasions after Ukraine gained Independence, Russian authorities promised the Crimean Tatars significant benefits if they supported Russia’s claims to Crimea.

One could argue that the continuing loyalty of the Crimean Tatars to Ukraine is partly the result of a simple strategy – the enemy of my enemy is my friend – with Russia perceived as their main historical enemy. But there is another important explanation – old ties and friendships linked to the dissident experience.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Crimean Tatars engaged in large-scale protests, demanding they be allowed to return to Crimea. Such protests were unprecedented in the Soviet Union. During this crucial period — when they greatly needed help and support — the most determined advocate of the Crimean Tatar cause in Moscow was the Ukrainian dissident Petro Hryhorenko.

The Crimean Tatar cause eventually became the focus of Hryhorenko’s human rights activities. His stubborn defence of the Crimean Tatars eventually led to his forcible detention in psychiatric institutions. Many years afterwards, in the 1990s and later, the Crimean Tatars continued to honour his memory. The Crimean Tatar leadership also maintained close ties with other Ukrainian dissidents, such as Viacheslav Chornovil.

To this day, for example, Mustafa Dzhemilev, one of the last prominent veterans of Soviet dissent, remains an active and respected figure of authority among the Crimean Tatars. His loyalty to Ukraine is, no doubt, partly a result of his interactions with other dissidents during the Soviet period.

The “dissident factor” also helps to explain the consistent loyalty to Ukraine of the Crimean Tatars.

Ukraine’s dissidents and human rights

Ukraine’s dissidents were not initially acquainted with the theory and practice of human rights in the broader non-Soviet interpretation. This was not surprising given the isolation of Ukraine and, for that matter, the entire Soviet Union from the outside world. The situation only changed, gradually, after Stalin’s death.

The first dissident activities in Western Ukraine consisted of small conspiratorial groups that generally followed in the traditions of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), a right-wing political organization espousing nationalist ideals, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the military wing of OUN, which operated during WWII and several years afterward.

These conspiratorial groups did not stress the importance of human rights, although they largely rejected violence as a means of achieving their aims. Outside of Western Ukraine, the initial emphasis of the “Shistdesiatnyky” (Sixtiers) was on cultural and national rights, e.g., language rights and the problem of Russification, rather than on general human rights.

Prior to 1968, an important source of information about human rights issues was Eastern Europe, especially Poland and Czechoslovakia, and these countries also served as major conduits for smuggling samvydav materials from Ukraine to the West. This changed, however, after the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Ukrainian poets and writers of 1960s (from left to right): Ivan Svitlychnyi, Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Liolia Svitlychna, Hryhoriy Syvokin’, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, Ivan Drach. Source: Ukrainian institute of National Memory

Ukraine’s mainstream dissidents also began to cooperate more actively with Moscow’s dissidents, who had greater access to information from the West, and who were generally advocates of a universalist human rights approach. This had a significant impact on the thinking and activities of Ukraine’s dissidents, who began to consistently use human rights language and tactics to legitimize their activities.

There was no consensus in Ukrainian dissident circles regarding the importance of general human rights. Some dissidents approached this issue in an instrumental fashion since a human rights framework provided a convenient means of promoting a national or religious rights agenda. In Kyiv, however, adopting a more thoughtful and meaningful human rights approach came quite naturally to individuals such as Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ivan Svitlychnyi, and the philosopher Vasyl Lisovyi.

Largely as a result of their labor camp experiences, even those dissidents from Ukraine who initially had little interest in general human rights issues quickly became aware of their significance. Here there were close contacts between dissidents from Ukraine and Moscow, including prominent human rights advocates such as Sergei Kovalev and Yuri Orlov. Ukraine’s dissidents greatly benefitted from these interactions, which provided them with useful insights into the international context of human rights.

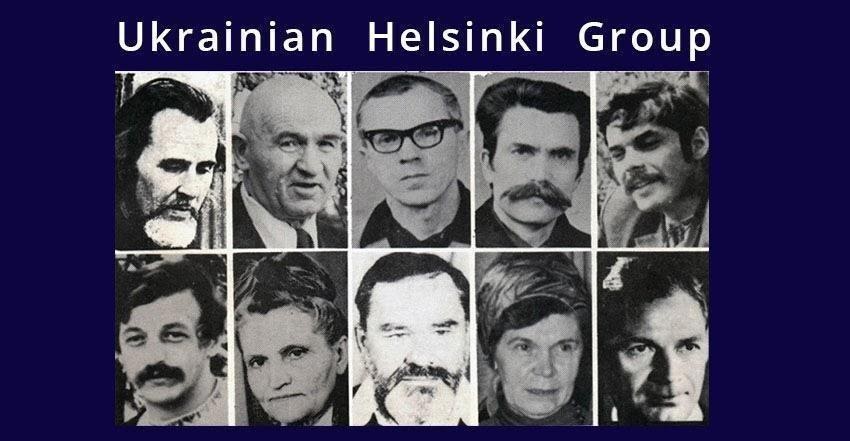

This was soon reflected in the instrumental work in the late 1970s of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group which, like other such groups, did everything it could (unfortunately, with little success) to force the Soviet Union to live up to its international human rights obligations.

When those who survived the camps (Stus was unfortunately not the only dissident to die there) were released for the last time in the mid- and late-1980s a few, embittered by their experiences, retreated into their private lives. But they were an exception. The majority returned to public life, which primarily took the form of activity in new organizations, such as the Ukrainska Helsinkska Spilka (Ukrainian Helsinki Union), a successor to the Ukrainian Helsinki Group; the Ukrainskyi Kulturolohichnyi Kliub (Ukrainian Culturological Club); Rukh; the Ukrainian Republican Party; and others.

The emergence of these organizations reflected a strong interest in the rapidly expanding opportunities for genuine civil activism in the late 1980s — now informed by a much greater awareness of the relevance of human rights. These activities had a significant impact on public opinion and the overall political scene, during this crucial period.

What followed, after Independence, was in many respects depressing. Given the harsh realities of corruption, socio-economic decline, and dirty politics in post-Independence Ukraine, it was only natural that many former dissidents became disillusioned. Some remained active in politics, sometimes at the local level, while others quietly and unassumingly took on the role of mentors for a new generation of activists.

The well-known writer and commentator Oksana Zabuzhko, for example, writes warmly about the long conversations she had with, and the support she received from, Yevhen Sverstiuk and Vasyl Lisovyi, among others. The ageing process also inevitably took its toll on the veteran dissidents of Ukraine.

Is this, then, the end of the story? Not quite. The cities of Kyiv and Lviv were pivotal throughout the history of dissent in Soviet Ukraine, but a third city — Kharkiv — now enters the scene. This city had an active and diverse dissident community whose beginnings date back to the early 1960s.

Its activists had a broad interest in a wide range of human rights issues early on and, in 1992, a number of enthusiasts founded the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG). By far, the group has for many years been the most active and productive human rights organization in Ukraine. The Kharkiv group is admired for its professionalism, and for going far above and beyond the call of duty. Their priorities include:

- carrying out investigations into individual cases of the violation of human rights;

- developing human rights education programs and promoting legal awareness through public actions, educational events, and publications;

- monitoring and analyzing the human rights situation in Ukraine (with a special emphasis on political and civil rights).

Noteworthy is the work of tireless journalist Halya Coynash. Her excellent, English-language reports on a variety of human rights issues are widely published, both in Ukraine and in the diaspora.

I mention this Kharkiv organization not just because of its current human rights activities, although they are very important. As part of their general activities, those in charge of this organization, including Yevhen Zakharov, have also devoted a great deal of time and effort to document, in detail, the history of dissent in Soviet Ukraine.

In addition to its crucial work on current human rights issues in Ukraine, the KHPG has also conducted outstanding research on the history of dissent in Soviet Ukraine. For example, the former dissident Vasyl Ovsienko, together with journalist Vakhtang Kipiani and others, have conducted extensive, insightful interviews with hundreds of former dissidents from Ukraine.

The KHPG’s current activities, as well as its efforts to document the history of dissent in Ukraine are rooted in the principles of resistance to arbitrary rule, speaking truth to power, and advancing human rights — all of which were fostered by the mainstream dissidents of Soviet Ukraine. Although these dissidents suffered greatly because of their adherence to values such as human dignity, freedom of speech and conscience, and cultural integrity, they have made their mark on history.

Conclusion

There is much to be learned from the experiences of the dissidents of Soviet Ukraine who have not, unfortunately, received the attention they deserve. And Kipiani’s book The Case of Vasyl Stus, and the film Zaboronenyi (The Forbidden), are the latest efforts to deal with and popularize the dissident theme in Ukraine. Much more along these lines can and should be done.

Even if the economic and socio-political situation in Ukraine improves significantly in the years to come, many human rights issues — including new issues that were not addressed by the dissidents of the Soviet period — will remain and will require attention. The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, and other similar organizations in Ukraine, have been inspired to a large extent by the dissidents of Soviet Ukraine. Although many of these dissidents have left, or are now leaving the scene, these dedicated groups are doing their best, often in difficult circumstances, to aid today’s ordinary citizens. They provide crucial aid to those who are abused in Ukraine’s prisons, mistreated by Ukraine’s corrupt court system, exploited in the workplace, and suffer from family violence.

The activities of these human rights organizations provide the dissidents of old with the best and most meaningful memorial imaginable. The values championed by Ukraine’s dissidents are universal, eternal, and will always be relevant. This is their true and abiding legacy.

IVAN (JOHN) JAWORSKY is Professor Emeritus, Department of Political Science, University of Waterloo (Canada). His research interests include dissent and its legacies in the post-Soviet region, regional issues and inter-ethnic relations in Ukraine, and civil-military relations in Ukraine. Between 2000 and 2010, he was a research associate for the “Building Democracy in Ukraine” and “Democratic Education in Ukraine” projects (Queen’s University). He is the author of The Military-Strategic Significance of Recent Developments in Ukraine (1993) and Ukraine: Stability and Instability (1995). He also prepared, for publication, the memoirs of Danylo Shumuk (Life Sentence, 1984) and Kostiantyn Morozov (Above and Beyond, 2000).

Read more:

- Carols against the USSR: the tragic 1972 Vertep and KGB’s mass arrests of Ukrainian dissidents (photos)

- From Stus to Sentsov: Ukraine’s Soviet-era political prisoners of the Kremlin

- Dissident artist Alla Horska murdered 45 years ago

- 12 facts about the Donbas that you should know

- Ukrainian dissident Krasivsky: Russia is our historical enemy. Only by fighting back can we survive

- The rise and decline of Donbas: how the region became “the heart of Soviet Union” and why it fell to Russian hybrid war