On 16 February 2017, the Supreme Court of occupied Crimea sentenced Ukrainian taxi driver Andriy Zakhtey to six and a half years in jail. He was accused of aiding supposed Ukrainian “saboteurs” who Russia’s FSB said had planned to attack Crimea in 2016. Independent lawyers were unable to access the 42-year old Ukrainian until his transfer to Moscow, where he told about how he was tortured after being detained. After returning to Crimea, Zakhtey refused the services of independent lawyers – one of the conditions of his plea deal. Zakhtey’s “confessions” to the FSB about the supposed “saboteur plot” were broadcast on Russian state TV, but an expertise of the weapons he supposedly handled revealed he never touched them. Moreover, he couldn’t even name any other supposed participants of the “plot,” simply because he didn’t know anyone else.

Zakhtey’s case demonstrates how, with the help of torture, falsified proceedings, and state-controlled media, the occupation authorities in Crimea fabricate propaganda myths to demonize Ukraine, sentencing away its live victims to many years of prison.

Here starts the “Crimean sabotage” scam

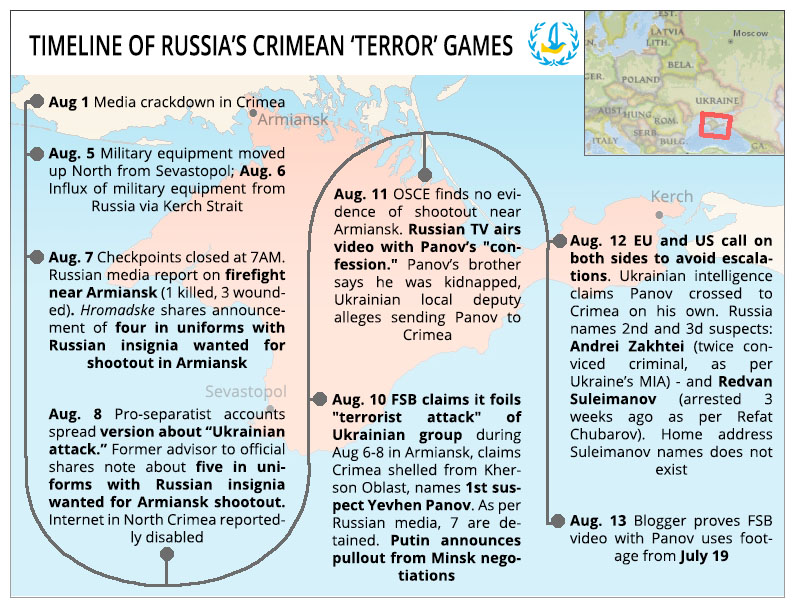

On the morning of 7 August 2016, when Russian border guards closed the border between occupied Crimea and mainland Ukraine. Witnesses told about sounds of shooting, but the information was contradictory. Closer to lunch, messages about the arrival of a Ukrainian sabotage group to Crimea and its clashes with Russian armed forces appeared, and additional military equipment and forces arrived at the border. Locals were told that law enforcement was searching for deserters from the Russian army who had fled with weapons. The internet in northern Crimea went on and off – operators claimed that the problems were technical, but the Russian senator for Crimea Olga Kovitidi claimed that the internet was blocked as part of “safety measures.” The Ukrainian Ministry of Defense denied Russian claims even before an official statement was made – Vladislav Selezniov, speaker for the General Staff of the Ukrainian Army, said that the information about a sabotage group which arrived in Crimea from mainland Ukraine was “provocative and not corresponding to reality.”

The situation got more and more tense, with military equipment arriving from Russia for the “North Caucasus 2016” military drills through the Kerch Strait. Only on 10 August did the FSB make a press statement announcing that it had foiled terrorist acts prepared by the Chief Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, that a group of saboteurs had been detained on 7 August, one FSB officer had been killed in the process (later it was announced that a contract soldier was killed too), and that 20 explosive devices, ammunition, mines, grenades, and weapons in service with special units of the armed forces of Ukraine had been discovered. The Russian media Kommersant wrote, citing its sources in the law enforcement, that during that operation two saboteurs were killed and three detained.

This version seems credible, given that Putin used the Crimean news to announce Russia's pullout from international peace talks on the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

This version of the FSB later became official, but underwent many corrections. The two killed “saboteurs” were never found.

Televised “confessions” and sentences on other charges

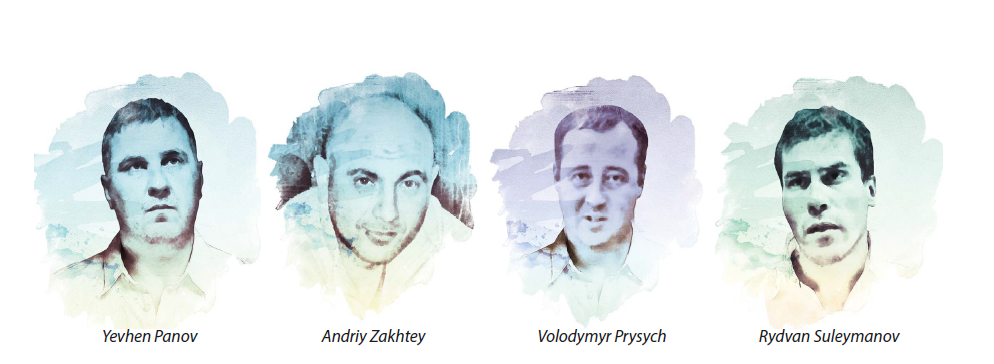

Overall, nine Ukrainians were arrested under accusations of sabotage. Yevhen Panov and Andriy Zakhtey were arrested in early August 2016 and accused of planning terrorist acts and targeting critically important parts of Crimean infrastructure. Volodymyr Prysych and Rydvan Suleymanov were arrested in the following weeks.

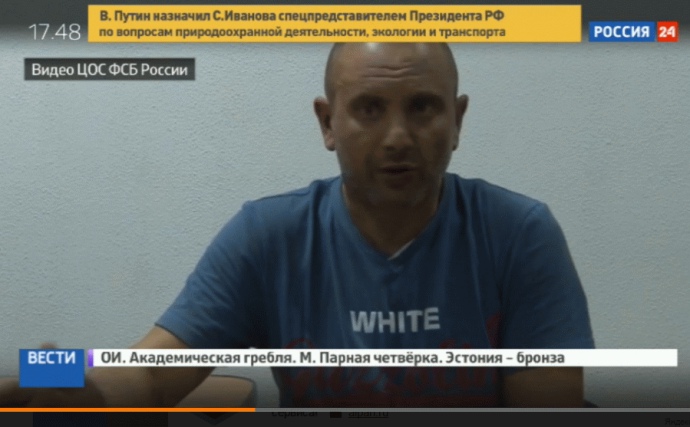

All four gave televised “confessions” where they claimed, respectively, to have worked for Ukrainian military intelligence to plant bombs in the Simferopol Airport and Bus station and record the movement of Russian military technology.

The case collapsed. The weapons stockpile which Panov and Zakhtey allegedly were connected to bore no traces of their DNA and there are grounds to believe that both Panov and Zakhtey had been lured to the place where they were captured. Panov, Zakhtey, and Prysych had subsequently said they had said what they were told to, under torture. Crimean Tatar Mejlis head Refat Chubarov informed, Suleymanov, a Crimean Tatar, had been detained already three weeks before the incident. He lives in Crimea, but in his video “testimony,” he names his address as Kosmichna 38, Zaporizhzhia (mainland Ukraine). This address does not exist - anybody can check in google maps.

Since then, Prysych has been sentenced on entirely different charges - of possessing drugs, which he claims appeared in his van half a day after he was seized, and Suleymanov had been sentenced under accusations of making false bomb threat calls, but not of using weapons or explosives, which indicates the initial testimony was forced out of him.

Zakhtey has chosen to collaborate with the investigation, and his testimony radically differs from his initial one, where he claimed he was tortured into saying what was required of him. Panov has refused to collaborate with the investigation, despite being promised a 5 year sentence instead of 20 years if he acknowledges his “guilt.”

In November 2016, FSB operatives announced they had captured a new batch of saboteurs. This time, they were military experts of the analytical center “Nomos” Dmytro Shtyblikov and Oleksiy Bessarabov, as well as former Ukrainian military servicemen Volodymyr Dudka, Oleksiy Stohniy, and Hlib Shabliy. This time, the FSB officers supplemented the “saboteurs case” not only with new prisoners but also with ridiculous pieces of evidence such as a “Right Sector business card,” which had been a symbol of Russian fake news since 2014, or airsoft guns passed off as “real” weapons.

Despite the televised confessions of the men alleging they were planning sabotage attacks in Crimea under the command of the Ukrainian intelligence on Russian state TV, Oleksiy Stohniy has been sentenced for a different article altogether: illegal possession of firearms, which indicates that the whole “confession” show is a setup, as the men had “testified” to working as a group. The Crimean Human Rights Group considers the men political prisoners due to the staged nature of their televised “confessions” and denial of right to a proper trial.

Torture, KGB-style

Before the “confessions” of Zakhtey and Panov were publicized in Russian media, they were taken to the Kyiv district court of Simferopol, where they first saw each other, and were arrested for 15 days for “swearing and harassing passers-by.” They appeared in the same court on 13 August 2016 and were arrested for two months under accusations of preparing sabotage. According to both, law enforcers staged the first falsified arrest in order to extract “confessions” from them via torture.

“They beat me with an iron pipe in the head, back, kidneys, arms, and legs; they tightened handcuffs from behind until my hands became numb; they hang me up by handcuffs: my knees were bent, the handcuffs were fastened slightly below the knees, an iron stick was inserted under the knees, and then two men took it from both sides and lifted this stick with me, which caused wild pain. Apart from that, they bound my penis until it turned blue and during this, the men asked: ‘Who did you come to blow up?’ I couldn’t answer this question, because I had no such goal, and I didn’t understand why they thought this… They fastened electrodes from an electric shocker to the knee of my right and left leg and lower back, turned on the current, as a result of which I fainted. I was brought to consciousness with water. My lips cracked from the electric shocks,”

Yevhen Panov later described the torture he was subjected to during six days in a complaint to the Investigative Committee of Russia.

Panov was arrested not at the place of the shootout, but at the border crossing on the night of 7 August 2016. The Russian border guards asked him to exit the car, took him to a wagon, hit him on the head and taken to some room where he was tortured for several days. The state lawyer Olga Pomozova was invited to open proceedings, but did not react to Panov’s story about the torture.

Panov told that he first served in the 56th

brigade of the Ukrainian Army (which he indeed did serve in 2014) and then entered a sabotage group for “working” in Crimea, and named his commander Volodymyr Sedyuk and fellow servicemen in that brigade as his co-conspirers in a plan to detonate the ferry station in Kerch, petroleum base in Feodosiya, the Titan chemical factory and several other objects. He told about a weapons stockpile in a cemetery, where the group was supposed to get its explosives and weapons.

While the FSB were filming Panov’s “confessions,” Zakhtey was being tortured in the next room, writes journalist Anton Naumlyuk.

“The scars on my hands appeared because the FSB operatives had handcuffed my wrists very tightly. When I was tortured with electricity, I jerked strongly, from which wounds appeared on my wrists. I was tortured with electricity for two days. First they attached the electrodes to my legs and buttocks, turned on the current, demanded to confess in committing a crime. I said that I was a usual taxi driver and came to the place of the shootout on the call of a client, but I continued to be tortured. Furthermore, the electrodes were attached to my genitals and I fainted several times,”

Zakhtey later told his lawyer Ilnur Sharipov. The state lawyer Oksana Akulenko, who was summoned to open proceedings, saw the wounds, but didn’t react to the obvious signs of torture.

Zakhtey also recorded a “confession,” but didn’t provide any names because, as he explained later, “he didn’t know anybody.” His “confession” states that he was supposed to meet the saboteur group on his car and transport them.

Expertise contradicts FSB story; Zakhtey makes plea deal to save family

The 42-year old Zakhtey was born in the Lviv Oblast, where he was sentenced for robbery and forging documents in 1998 and 2008. But, in the words of his wife, he started a new life when he married and decided to move to Crimea after the birth of his daughter.

His friend Yuriy Fliunt from Kyiv helped him buy the minivan that he drove in Crimea. This is the only person that Zakhtey names in his “confession” as ordering him to transport “people with some load” from the Risove village.

On the night of 7 August 2016, Zakhtey indeed set out to meet a group of clients in Risove. While he was waiting for them in his minivan, people who introduced themselves as FSB officers entered his car and they drove away to a bridge. There, the FSB employees exited the vehicle and a shootout started which lasted for 2-3 minutes, when, apparently, one FSB operative was killed, and the shooters managed to escape.

Regarding the latter, he was stripped of Russian citizenship, and his passport was invalidated. But Zakhtey himself asked to have his Russian citizenship withdrawn, saying he was “very disappointed in the judicial and law enforcement system of Russia, the absence of democratic values and the rule of law”; now he has only a Ukrainian passport left. Meanwhile, the materials of the case state that Zakhtey had received a Russian passport based on falsified data on his registration in Crimea.

The criminal case describes his “saboteur activity,” saying that Zakhtey had entered a deal with an organized group created by persons “unidentified by the investigation” in order to commit sabotage acts in Crimea, “in order to undermine the economic security and defense capabilities of the Russian Federation.” He is accused in buying a car and starting to conduct transportations “in accordance to the role given to him.” It is on this car that Zakhtey supposedly arrived during the night at the determined spot and took a “black plastic bag with ammunition, explosives, and other objects of criminal activity of the group, hiding them in his automobile.” After this, according to the accusation, he came to pick up the group, but was intercepted by the FSB.

Independent lawyers were able to access the men only in Moscow, where they were sent away from Crimea in November 2016 and told about the torture they went through. After they returned to Crimea, Zakhtey made a plea deal with the investigation, refusing independent lawyers, for which he reportedly was promised no more than five years of jail – a promise that was not kept, as the prosecutor had asked for seven instead. The court hearings in the case were closed, with journalists being present only at the reading of the verdict. Zakhtey was finally accused in acquiring and using falsified documents, storing and transporting weapons and explosives as part of a group, and, most importantly, in preparing the sabotage attack.

“I have a feeling we just ended up as pawns in someone’s game,” said his wife Oksana. “Andriy was simply used.”

She left to Lviv Oblast with her daughter and saw her husband only a few times during prison dates. Reportedly, one of the reasons for Zakhtey’s plea deal were threats to his family.

“Oksana isn’t arrested, Sashenka is not in the orphanage. I did what’s most important for me,” said Zakhtey.

He is sentenced to 6.5 years of a strict regime penal colony and a RUB 220,000 fine. His defense already said they will submit an appeal.

Read also:

- Why Russia manufactured Crimean “terrorism”. Five versions

- “Crimean saboteurs” – latest victims of Kremlin’s hostage strategy

- Expert community outraged over new FSB arrests in Crimea

- A timeline of Russia’s Crimean “terror” games | Infographics

- Human sacrifices for the Kremlin’s propaganda machine: meet the “Crimean saboteurs”

- Putin’s Crimean miscalculation

- Document suggests “terror shootout” in Crimea internal Russian conflict