More than a half-century ago, the USSR attempted to apply for membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

How did the Alliance meet this idea, and why was it never accepted?

On 31 March 1954, the Soviet Foreign Ministry sent identical notes regarding the possibility of joining NATO to the governments of the three Western powers: France, Great Britain, and the United States.

In those notes, Moscow insisted that the North Atlantic Treaty in the present form was certainly an “aggressive pact” but its nature could change if the USSR, the principal member of the former Anti-Hitler coalition, joined it. The Soviets also expressed their hope that the great powers would not allow the participation of Germany (its division into the two states was not seen as irrevocable) in any military bloc.

On April 7, Moscow’s proposal was discussed at the session of the North Atlantic Council in Paris. The minutes of that meeting has been declassified and is available online on the NATO Archives website. The members of the Alliance interpreted the proposal as a Soviet propaganda step targeted primarily at the Western public opinion. To them, it looked implausible that the Kremlin would accept the requirements of NATO, primarily,

- the comprehensive control over its military planning and

- securing democratic rights and freedoms in the USSR and the countries within its current area of influence.

During the discussion in Paris, the Danish representative emphasized that the very establishment of NATO was a response to the failure of the United Nations to ensure effective collective security in the years following World War II. Everyone certainly bore in mind the Korean War of 1950—53, when the USSR and China confronted Western powers. The Kremlin, he maintained, contributed to this failure by its abuse of veto in the UN Security Council.

The delegates of other member states supported this view. The representative of Italy warned that since the decisions of NATO collective bodies must be unanimous, the Soviet Union could have used veto to paralyze this organization alike and, hence, the Alliance would have become just as ineffective as the UN. The participants of the session also criticized Moscow’s attempt to thrust the non-participation of West Germany in the European defense initiatives.

In a few weeks, the American, British, and French governments officially responded to the Soviet proposal, which they called “completely unreal.” NATO, their joint note stressed, was based on the principles of individual liberty and the rule of law, and its effective institutions could not be replaced with “illusory” ones. The three states urged the Soviet Union not to prevent the UN from exercising its global security functions in accordance with its Statute.

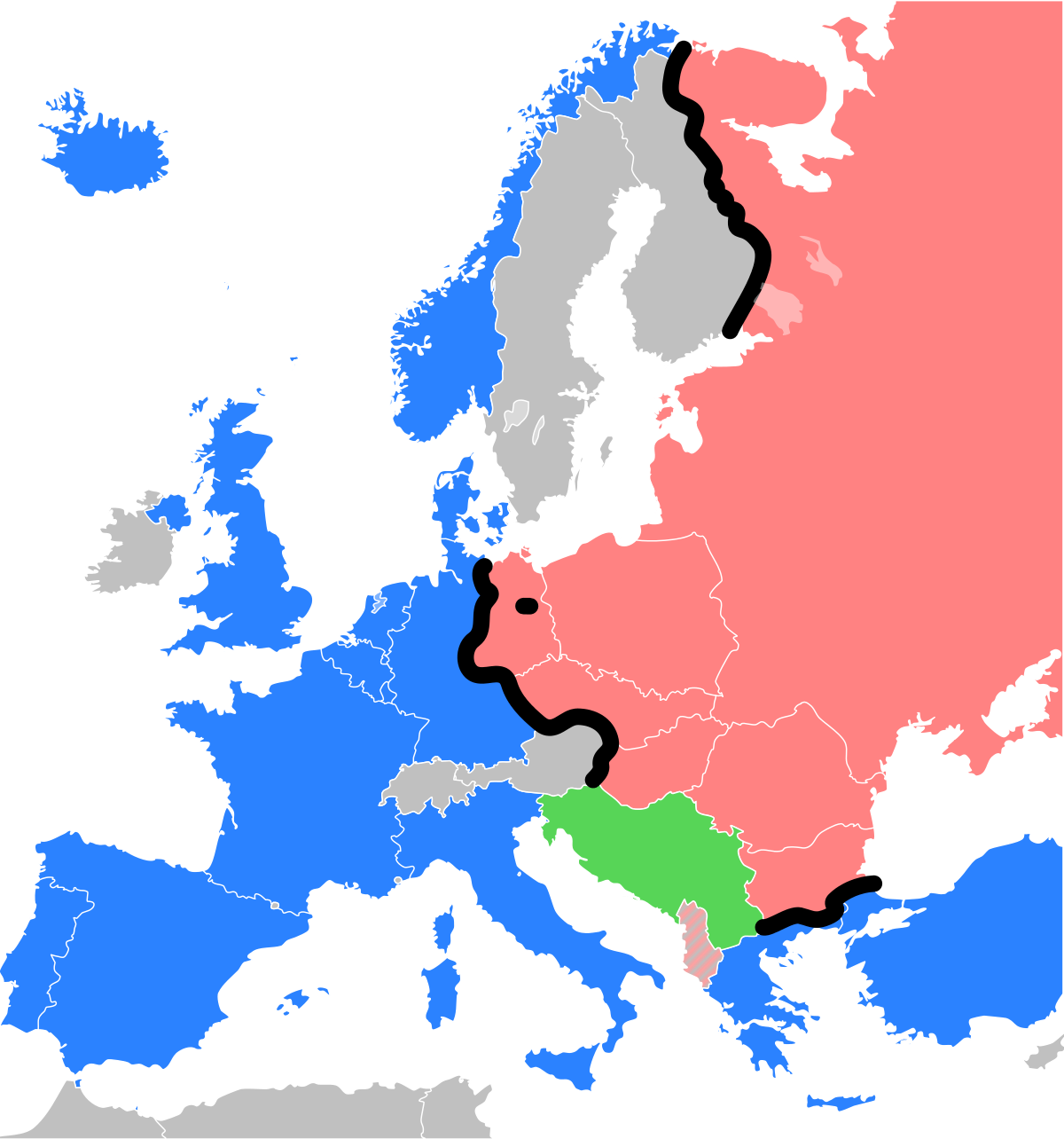

While the Soviet Union was denied the entry into NATO, the Federal Republic of Germany, which had undergone the process of denazification, received the invitation in the coming months. On 5 May 1955, the West German Bundestag ratified the North Atlantic Treaty.

Only nine days later, the USSR and its seven Central and East European satellites announced the formation of their own military alliance, the Warsaw Pact (which allowed the presence of the Soviet armed forces in those countries and made possible the military intervention of the Kremlin, as it would happen to Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968). This completed the split of Europe into the two confronting blocs, which would last until 1990.