The anniversary of Ukraine’s independence is reason for reflection. Especially at the time when Ukraine’s sovereignty and well-being face so many external and internal threats. We gathered 25 moments of Ukraine’s independence – turning points in Ukraine’s newest history which brought us to 24 August 2016.

1. 1990: The declaration of state sovereignty

It seems that Ukraine’s declaration of state sovereignty was unavoidable. The document from 16 July 1990 envisaged the “the supremacy, independence, fullness and indivisibility of the authorities of the Republic within its territory and independence and equality in foreign relations;” however, it laid the ground for a signing of a new union agreement. Ukraine continued to remain in the USSR and its independence could not be recognized by any country.

2. 1990: The blue-yellow flag is raised in Kyiv

On 24 July 1990, a blue-yellow flag was raised above Kyiv for the first time in many decades. While battles between communists and proponents of the democratic bloc raged on in the Kyiv city council, a procession brought a sanctified blue-yellow canvas from Saint Sophia Cathedral to the main street, Khreshchatyk. The people took matters into their own hands.

3. 1990: The Students’ Revolution on Granite

Like 23 years after, it was students that came to defend Ukraine’s independence to Kyiv’s central square, Maidan, in the autumn of 1990. However, at that time it still carried the name of the October Revolution [the Russian Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 — Ed.]. Over two weeks in the October of 1990, students demanded that a new agreement with the USSR not be signed. Nearly 150 students from 24 Ukrainian cities went on hunger strike in the center of the capital, creating a precedent for the first Youth Velvet Revolution, later named the Revolution on Granite.

4. 1991: The Declaration of Independence of Ukraine

On 24 August 1991, Ukraine’s Verkhovna Rada held discussions from 10 in the morning to the nightfall. It discussed the single topic: “the political situation in Ukraine.” Between 30 and 50 thousand citizens chanted “Independence!” under the walls of the Rada, held blue-yellow flags and did not disperse until the Act of Declaration of Independence was signed. Opposition leader Viacheslav Chornovil brought a large blue-yellow flag into the session hall, but then-Rada chairman Leonid Kravchuk dared to raise only a compromise, paired the blue-yellow Ukrainian historic and the red-blue Soviet flags. This met the disapproval of the demonstrators outside, and to avoid them taking down the parliament doors, the future first President of Ukraine finally lowered the Soviet flag.

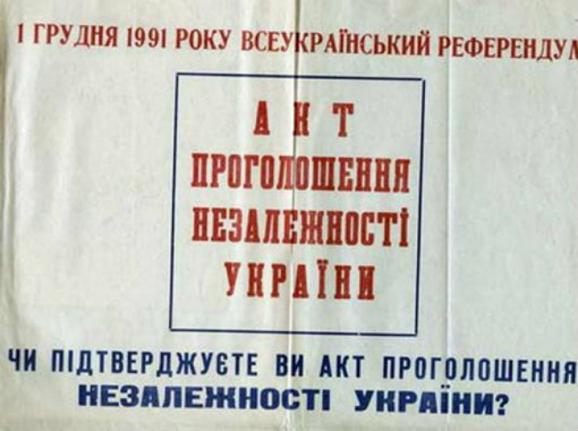

5. 1991: Referendum on independence and elections of the first President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk

90.32% citizens supported the Act of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine. On the same fateful day, Leonid Kravchuk became the country’s first President, by far beating Viacheslav Chornovil. The latter, having died in 1999 “under mysterious circumstances,” never became Ukraine’s Vaclav Havel.

6. 1992: Hyperinflation and strikes

The first years of independence were a survival school for Ukrainians. No country of the world lived through such hyperinflation. Ukraine’s 1993 index of 10,000% still holds a world record. Enterprises shut down, prices jumped, currency notes were printed, miners holding protests rattled the asphalt with their helmets.

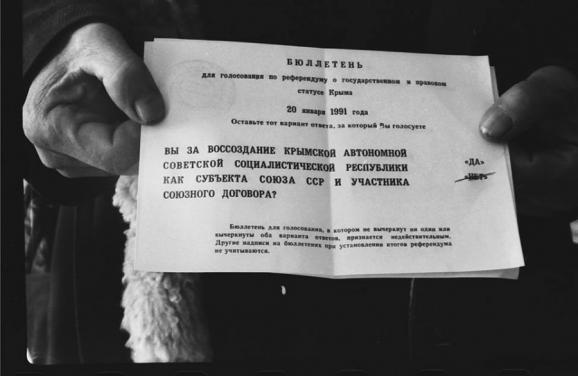

7. 1992: Crimea. Autonomy. Introducing and abolishing presidency

With Ukraine’s declaration of independence, Crimea ended up as a part of Ukraine. In 1992, the Crimean Parliament adopted the Declaration On State Sovereignty of the Republic of Crimea and the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea, which proclaimed the peninsula as an independent country within Ukraine, and established the position of the President of Crimea. Though these documents contradicted Ukrainian legislature, the Verkhovha Rada abolished them only in 1995, along with the presidential position.

8. 1996: Ukraine signs the Budapest Memorandum and gives up nuclear weapons

Ukraine set its course towards nuclear disarmament already in the Declaration on State Independence: it was decided that nuclear weapons were “not to be accepted, produced, or purchased.” The USA, Great Britain, and Russia were chosen as the safety guarantors. On 5 December 1994, the Budapest Memorandum was signed, and on 2 June 1996 Ukraine finally lost its nuclear status. The weapons arsenal was handed over the Russia. In the memorandum, the guarantor states did not pledge using force to protect Ukraine’s territorial integrity and its text did not specify its ratification, i.e. is not mandatory for execution.

9. 1996: Ukraine adopts its first Constitution

The first project of the Constitution appeared already in 1992, but was ratified only on 28 June 1996. This situation is typical for other post-socialist countries. Lithuania, which was the first to leave the USSR, adopted its Constitution right away – in 1990. Belarus finished the task only in 1994, and Poland – in 1997.

10. 1997: A wide-ranging agreement on cooperation between Ukraine and Russia and the stationing of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Crimea is signed

The agreement to station the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Federation in Ukrainian Sevastopol was signed on 27 May 1997. It was agreed that it would stay there for 20 years, but in 2010 that seems too little for President Yanukovych, and the term was extended for another 25 years with the Kharkiv agreements. After illegally annexing Crimea, Russia decided to denounce the agreements, as if international agreements still held any value for a country-aggressor.

11. 2000: Investigative journalist Gongadze is murdered. “Ukraine without Kuchma” protests

The decapitated body of Georgiy Gongadze, a journalist in opposition to the regime of Leonid Kuchma, was found on 2 November 2000. The disclosure of Kuchma’s phone intercepts, in which he was heard plotting against the journalist with associates, was the reason for the “Cassette Scandal” which led to “Ukriane without Kuchma” protests. Oleksiy Pukach, the murderer, is serving a life sentence in prison; Yuriy Kravchenko, one of those involved in the case, committed “suicide” with two shots to the head, Volodymyr Lytvyn still continues his political activities, and Leonid Kuchma still represents Ukraine at the negotiating table in Minsk.

12. 2004: The Orange Revolution and Viktor Yushchenko’s victory

The epic presidential race of 2004 and the voting results falsifications by Viktor Yanukovych, the pro-Russian candidate and Leonid Kuchma’s choice of successor, made Ukrainians come to protest at the Maidan Square in Kyiv to conduct a peaceful revolution. The victorious Viktor Yushchenko had his charm eaten away by dioxin poisoning which scarred his face for life, and his charisma was destroyed by internal party conflicts. Yushchenko gave Ukraine the example of a successful revolution and taught them to never fall in love with the leader.

13. 2006: The revenge of the Party of Regions at the parliamentary and presidential elections

It wasn’t long till the pendulum swung the other way. In 2006, Yanukovych’s Party of Regions received over 30% votes at the parliamentary elections, creating the largest faction. In 2010, Viktor Yanukovych became President, having won from Yuliya Tymoshenko with a number of votes equal to the statistical error. The revenge was sweet – Yanukovych hurried to build up a vertical of power and secure full presidential powers, canceling Yushchenko’s changes to the Constitution for a parliamentary-presidential republic.

14. 2011: Yanukovych arrests Tymoshenko and Lutsenko

Nobody cared about Yushchenko in 2011. Having received 5.45% of the votes at the presidential elections, he was sent to the museum of shattered hopes of the Ukrainian nation, to the shelf of the lover of bees and national ideas. But such players as Yuriy Lutsenko and Yuliya Tymoshenko presented more danger to Viktor Yanukovych. It wasn’t difficult for him to find “reasons” to open criminal proceedings against both. Yanukovych, as it befits dictators, created a host of prominent political prisoners.

15. 2012: Hosting the European Football Championship

A feast in time of plague, the 2012 UEFA European Championship (Euro-2012) exposed Ukrainians to Europe, and the other way around. Costumed and painted Swedes and Dutchmen drank inexpensive Ukrainian beer in the arms of beautiful women and did not understand why the party must end. Only a few Ukrainians screamed about the corruption and wasting public funds. The glamor of renovated airports and sky-high prices of hotels still did not rectify the impression of devastated roads and crazy minibus taxis, which stopped “at the stop.”

16. 2013: Yanukovych fails Ukraine’s eurointegration

In 2013, everything suddenly collapsed. First, state funds were spent to promote eurointegration among Ukrainians, but later in the year Yanukovych made a 180-degree turn toward Moscow. Yanukovych didn’t understand the people over whom he became president and didn’t become the first to lead Ukraine to Europe. Edward Lucas, the editor of The Economist, wrote that Putin achieved an expensive victory by offering to provide a $15 billion loan to Ukraine and slash natural gas prices in return for Ukraine ditching its EU aspirations. At the Vilnius Summit of the Eastern Partnership countries in November 2013, Yanukovych refused to sign the Association Agreement. And by doing this, in fact, he signed his own verdict.

17. 2013: The Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity

Young people “with umbrellas, tea, and coffee” were already waiting for the short-sighted Ukrainian President at the main square of the country. None of them knew then that their gathering would trigger a butterfly effect throwing the geopolitics of the entire world off balance. The vicious beating of the activists by riot police in November 2013 seemed like a fairy tale when compared to the horror of the first corpses carried out of Maidan in the winter of 2014. “Only Ukrainians are dying for freedom under the EU flag,” western analysts would write. “We are deeply concerned,” politicians would continue to say one, two, and three two years later, while the Yanukovych officials responsible for the killings still have not been brought to justice.

18. 2014: The illegal annexation of Crimea

After Yanukovych carted off his illegally acquired assets and fled to Russia in February 2014, Ukraine was able to exhale in relief, but only for a fleeting moment. Real trouble was advancing from the East. Putin planned the annexation of Crimea a long time ago, his former advisor Andrei Illarionov insists. The Ukrainian army was destroyed gradually, and the foundations for separatism were laid over many years. The Russian military medal “For the Return of Crimea” specifies the dates of the Kremlin’s special operation to annex the Ukrainian peninsula as 20 February – 18 March, 2014. That’s when the unmarked Russian troops arrived and suppressed all military and civilian resistance to the Russian aggression while the Ukrainian interim government still grappled with the changeover of power after the Euromaidan revolution. The illegal referendum unrecognized by the world took place two days before the completion of the Russian special operation.

19. 2014: The Russian occupation of eastern Ukraine

As it turned out, propaganda was stronger than anybody could imagine. The mythology of so-called “Novorossiya” and “blood-thirsty Ukrainian nationalists” suddenly captured the hearts not only of “miners and tractor-drivers” of the Donbas, but famous analysts, who suddenly became Putin-sympathizers. Out of its ambitious plan to create a land corridor to Crimea, Russia managed to bite away only a small piece of Ukrainian territory in Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, and only after investing a huge amount of resources including its regular military servicemen, mercenaries, heavy weapons, and a large army of propaganda trolls.

20. 2014: President Petro Poroshenko’s victory at presidential elections

The President brought a new hope. With a fluent English and an ability to represent Ukraine well in negotiations with the West, experienced and baptized by Euromaidan, he went to the elections with promises to return Crimea and finish the Anti-Terrorist Operation in Donbas. On 25 May 2014, Petro Poroshenko won in the first round of elections, calling not to spend the state budget on another, as he said, unnecessary tour.

21. 2014: The war in the East

The Anti-Terrorist Operation wasn’t supposed to last more than a year. The undeclared Russo-Ukrainian war that started with the occupation of Crimea continues to this day. Volunteers can’t perform all the functions of the state during a war, including providing for the army and rehabilitating its wounded. The war illogically continues to take new and new lives, presumptuously calling itself a “ceasefire.” Ukraine found itself trapped by a military conflict on its eastern border with war crimes, over a million of refugees, and a humanitarian catastrophe.

22. 2014: Ukraine signs the Association Agreement with the EU

In an unprecedented move, the agreement was divided into two parts (an economic and political one) and signed in two stages: 21 March and 27 June 2014. Only a few signatures, but they triggered the largest redistribution of power on the continent. The Association Agreement, which doesn’t promise Ukraine membership in the EU, was ratified by each EU country individually. In April 2015, The Netherlands held a referendum which held off the ratification of the Agreement with the country.

23. 2014: A ban on Communist ideology and “raining Lenins”

Lenin statues all over Ukraine fell like apples in autumn after the monument in Kyiv was toppled during Euromaidan. The young generation of Ukrainians born under independence was settling scores with the bygone era. Public pressure left the authorities without a choice: on 9 April 2015, Ukraine banned the promotion of Communism and Nazism and adopted an ambitious plan to rename thousands of streets and towns and destroy all the Soviet-era symbolics, such as stars, sickles, and hammers.

24. 2015: The creation of a new police and reforming Ukraine’s Ministry of Interior

“Reforms” to Ukraine’s authorities are like a red rag to a bull. Western lenders and Ukrainian voters alike demand them, while the authorities resist them. One of the most easily seen reforms is the creation of a new patrol police force, which supposed to kick off a reform of the Ministry of Interior. The reform process in Ukraine drives on, sometimes compensating each new step forward with a step back, but in any case having allowed the adoption of more reform-oriented legislation over the two years after Euromaidan than in the previous 23 years.

25. 2016: Russia returns 3 political prisoners to Ukraine, 28 still remain imprisoned by Russia

The exchange of captured pilot Nadiya Savchenko for two Russian servicemen captured by the Ukrainian army in Donbas in 2016 gave hopes for a start of the process to return other Ukrainians illegally imprisoned by Russia on trumped-up charges. The exchange of two more prisoners, Gennadiy Afanasyev and Yuriy Soloshenko, and escape of Yuriy Ilchenko and Yuriy Yatsenko, currently sets the number of hostages of the Kremlin at 28. With mounting repressions in Crimea, their number will likely increase.