Two leading Russian analysts, Vladislav Inozemtsev and Igor Yurgens, have argued that the European Union has failed to provide Russia with a path to Europe and thus have “rejected” Russia. But in fact, Lilia Shevtsova says, that is exactly backwards: Europe hasn’t rejected Russia – Russia has rejected Europe.

Many Russian liberals, the Moscow commentator writes in “Novaya Gazeta,” consistently criticize the Kremlin’s domestic policies but fall in line with Vladimir Putin when it comes to foreign affairs and especially when they are talking about the attitude of other countries toward Russia.

On the one hand, of course, this is nothing more than the latest example of the old principle that “Russian liberalism ends at Ukraine.” But on the other, and more fundamentally, it reflects an unwillingness to consider the links between domestic and foreign policy and the way that must play out in relations with structures like the EU.

In her current article, Shevtsova takes Inozemtsev and Yurgens to task for their suggestions that the EU has failed Russia because it has not offered it a path to full membership like the one it provided Germany, which as a result has become the most European of states.

Given the Putin’s regime to keeping itself in power forever and extracting as many resources from Russian society as possible, there could be no basis for Europe taking in Russia as a member, Shevtsova points out. Russia would never accept going through the EU application process and would only become more convinced that Europe was “rejecting” it.

What it wanted and wants is something else, something Europe could not concede without betraying the principles on which Europe is based, a reality that is highlighted by what Shevtsova describes as Inozemtsev’s view about the biggest mistake the EU has made: “’the artificial division of the post-Soviet space… into Russia and “other” countries.’”

In brief, the Moscow commentator continues, Inozemtsev sees “Europe’s mistake” as rooted in “the recognition of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the new independent states” because that represents a challenge to “’historic Russia’” whose capital Moscow should be the capital of a new post-Soviet integration project.

If Europe were to accept that, Shevtsova says, it would not be Europe; and what would emerge would be nothing but “a variation of the USSR but in a still more repressive form.” No country that wants to be part of the EU has or could have similar pretensions. But Russia “was not prepared for what Eastern Europe and the Baltic countries were – subordination to a super-national structure.”

In fact, Shevtsova points out, Europe went far further in that direction than it should have, making “a bet on leaders” in Moscow rather than insisting “on standards” of behavior. That led the Kremlin to think it could continue to make demands for “the right to influence European structures even though it has refused to follow European principles.”

By 2000,’ she continues, “it had become obvious that Russia had turned out to be the most dramatic failure in European politics. But it wasn’t easy for Europeans to recognize this because they had devoted too much time, energy and money to it.” Consequently, they “continued to play at partnership,” and Moscow “continued to play along.”

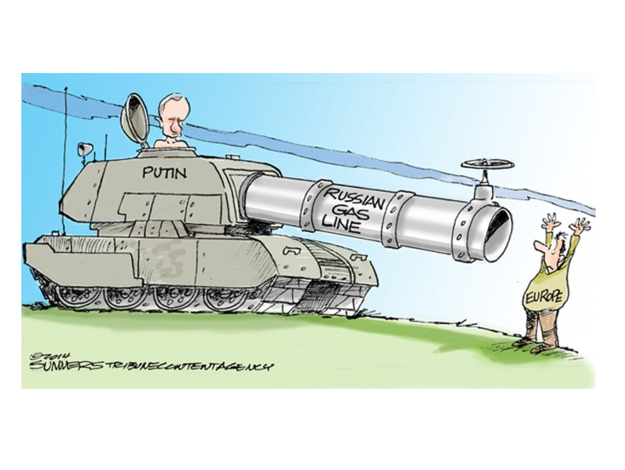

“After the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004, it was possible to sense that the love story between Russia and Europe had ended. The Kremlin had not received what it wanted – the role of partner with a super-status and the right of veto over decisions of the EU and NATO,” something that would have put Moscow above those institutions rather than under their rules.

By that point, it had become clear that “Europe had not been able to europeanize Russia, but the Russian ruling class had been able to integrate itself into Europe on personal basis.” And at the same time Europe proved “unable to respond to the challenges of an autocracy which was trying to survive by imitating liberal democracy.”

“The double standards of European politicians” – not the ones Moscow talks about but the real ones – and their willingness to make deals not only discredited liberal democracy but created the temptation and possibility for the Kremlin to play in Europe according to its own rules.”

Many in the West continued to argue that “’one must understand the Kremlin! One must give it what it demands – that perhaps will calm things down.’” Such attitudes mean, Shevtsova says, “the European elite bears a share of responsibility for the fact that Putin has not seen any ‘red lines.’”

But Putin’s “adventure in Ukraine,” she continues, “forced Europe to finally come out of the paralysis” and allowed Germany to become a power in place of “the toothless Brussels” and “the guarantor of a new European unity.” Many Europeans don’t want to see this even now, but “Europe will try to find a new formula for relations with Russia balancing containment and dialogue.”

“However much the Kremlin seeks to sponsor its ‘Trojan horses’ in European capitals and to buy up left and right extremists as well as European parliamentarians and to co-opt European business,” she argues, Putin will fail. “Europe will search for a way out of its twilight” because “it is a civilization with a powerful civil society” that has not lost its vitality.

Those who will continue to act in ways intended to avoid making Russia angry “will only help the Kremlin further cultivate in Russian society ‘the Weimar syndrome’ and justify the transformation of Russia into ‘a besieged fortress’” because that is how the Russian “genetic code” predisposes them to think regardless.