This article is part of the Essay collection “What does Ukraine think?”, published by the European Council on Foreign Relations, reproduced with permission. Original article and more essays on Ukraine here.

![President Poroshenko stands on the backdrop of his electoral slogan, Zhyty po-novomu [Living the new way]](http://euromaidanpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/jyty.jpg)

Reform agenda-setters: government, civil society, and the West

In an ideal world, citizens form policy agendas and elected officials implement policies to further these agendas. In practice, the political and economic elites that control the media are often able to impose their agenda on the public. In Ukraine, for example, a third of the population say they want to nationalise oligarchs’ property. However, media channels – in most cases owned by the very same oligarchs – avoid the topic. In Ukraine, three main groups currently form the reform agenda from above: the government, civil society, and the West. None of them necessarily have the same priorities as Ukrainian society as a whole.

Shymkiv made bold promises in the “Strategy of Reforms –2020”: Ukraine’s GDP per capita would increase from $8,508 to $16,000 by 2020; the country would become one of the top 20 countries in the world in which to do business; foreign direct investment would increase to $ 40 billion; the average life expectancy would increase by three years; and military expenditure would grow from 1 percent to 5 percent of GDP. [3]Shymkiv’s plans were similar to another 50 -page document titled “Coalition for Reforms”, signed by the new coalition in November 2014 – but, by then, defence sector reform had become the top priority.[4]

The population’s reform agenda

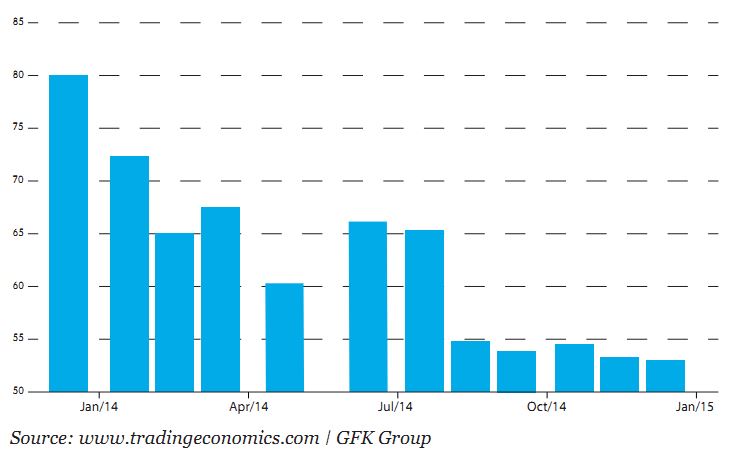

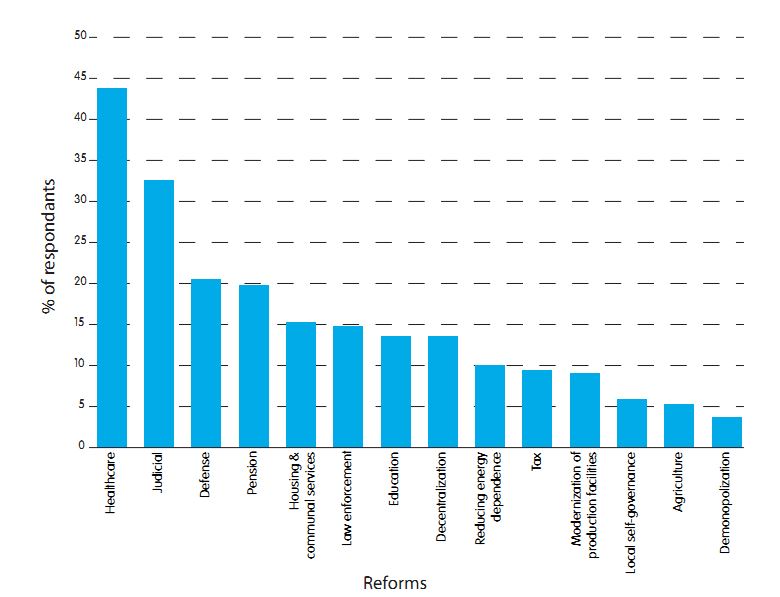

Sociological data confirms that the elite and the public do not share the same reform agenda. The economic crisis and the ongoing war in the Donbas are the two most powerful factors influencing public opinion, but polls show that Ukrainians are more worried about their own economic and physical survival than about reforming their country. Asked what they thought were the most urgent problems for Ukraine to solve, 79 percent of respondents said ending the war in the Donbas was most important.[5] Meanwhile, 48 percent said raising salaries and pensions was essential, 43 percent prioritised kickstarting economic growth, and 38 percent thought fighting corruption was urgent.[6] Another poll at the end of 2014 showed that ordinary citizens perceive reforms primarily as a way of both bringing governmental officials to justice and of improving their own economic situation[7]. The question “What are the reforms for you?” had 30 options from which to choose. The most popular choices were: scrapping MPs’ immunity (58 percent), raising salaries and pensions (51 percent), and scrapping immunity for judges (48.3 percent) and for the president (34.4 percent). The standard of living of ordinary Ukrainians has plummeted dramatically since the Euromaidan. Ukraine’s economy is in its second year of recession, as the war ravages industry and investment. The decline in real GDP in the third quarter of 2014 was 5.1 percent, after drops of 4.6 percent and 1.1 percent in the first and second quarters. The depreciation of the exchange rate of the hryvnia to the dollar between January and October 2014 was 58.9 percent. The consumer confidence indicator has deteriorated dramatically, from 80.3 points in January 2014 to a low of 52.6 points a year later (see figure 1).[8] Figure 1: Ukrainian consumer confidence

Trending Now

Between war and reform

The October 2014 parliamentary elections were supposed to dispel early frustrations with the lack of reform. The vote produced a pro- reform majority and removed most of the reactionary forces from parliament. But the new parliament has been slow to foster change. Some doubt that the current political elite will ever summon enough political will to enact meaningful change. Both the president and the prime minister have said that it is difficult to instate reform while Ukraine is at war. “After spending most of the day looking at military maps and studying the situation on the frontline, it’s not easy to switch straight away to addressing the subject of promoting peace”, Poroshenko complained at the end of January[10]. Civil society argues that the war should not serve as an excuse for everything, although while the war continues they temper their criticism. They also understand that there is an external enemy that could exploit any new unrest to create a hypothetical “Maidan 3”. The war has also refocused civil society’s attention from pushing for reforms in government to volunteering in the Donbas war. Not only did the war make citizens pay less attention to reforms, it also thwarted some of the reform processes. The lustration reform that started after the revolution as a result of bottom-up pressure aimed to clean the state apparatus of corrupt officials from the Yanukovych era and collaborators with the KGB. But the war has short-circuited the process. The anti -oligarch movement was also stopped as the oligarchs came to be seen as allies of the state in the war with Russia. However, Ukrainians understand that even if it is harder to reform during the war, structural reform remains a precondition for Ukraine’s ability to defend itself militarily and thus to survive. Ukraine’s military campaign has been constantly weakened by government inefficiency and corruption. The army leadership has not been lustrated and has not adopted modern methods of military command, creating considerable mistrust between NGOs supporting the army and its commanders.Conclusion

Ukrainians do want reforms, but they feel disoriented and endangered. It is hard to ask society to take the lead in reforms when the majority are either struggling to survive the economic crisis or worried about their personal security. The overall pace of reform is glacial, but there are several effective teams and individuals inside and outside the government striving to transform the country. The West should rely on these individual reformers and provide finance only in sectors that have concrete reform programmes, like that of the traffic police launched by Eka Zguladze. Ironically, Ukraine is still a long way from creating the kind of democratic model that the Kremlin clearly fears. But if the Russian regime manages to crush Ukraine’s ongoing democratic experiment and redraw the borders of Europe, the future of the whole of Europe will be insecure.Olena Tregub is a journalist, educator and civic entrepreneur. She led the Reform Watch project at the Kyiv Post which analyses Ukraine’s post-Maidan transformation and now works at the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of Ukraine.